Desk-Based Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hawthorns Cote Road, Aston, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2EB

Stow-on-the-Wold J10 A435 J11 CHELTENHAM A4260 Bourton-on-the-Water A44 A4095 A40 A361 J9 A41 GLOUCESTER A429 A424 A436 J11A A34 M5 Cotswolds A46 A4260 AONB A40 A4095 Burford M40 A435 WITNEY A429 A40 A417 A40 Carterton A4095 A415 A361 OXFORD CIRENCESTER B4449 J8/8A A419 A34 A415 J7 A417 ASTON A329 Lechlade- A4074 A4095 A338 A420 on-Thames A417 Abingdon Chitern Hills A433 A415 AONB Faringdon A415 A361 A338 A419 A429 A417 A4074 A420 A4130 Didcot Wantage A4130 SWINDON A417 M4 A4074 A34 J16 A338 J15 J17 A3102 A329 A4361 A346 M4 A420 J14 J13 READING North Wessex M4 Downs AONB M4 A4 Hawthorns Cote Road, Aston, Bampton, Oxfordshire OX18 2EB A40 A40 OXFORD Location CHELTENHAM Witney Hawthorns offers a collection of executive detached homes consisting of 2 bedroom bungalows and 4 & 5 Brize bedroom houses located in the village of Aston in the Norton A4095 A415 Ducklington Oxfordshire countryside. S T A N D L A K E Carterton D R The village of Aston has all the essentials of village Lew A O O A R D Hardwick N life - a church, a school and a pub. O T S B44 A 49 AD EYNSHAM R O A415 DOVER Aston is also home to the popular Aston Pottery and STATION ROAD nearby you will find Chimney Meadows, a 250 hectare nature reserve, rich in wildlife, along the banks of Hawthorns T S Brighthampton H T the Thames. Bampton ASTON R ABINGDON ROAD ASTON O D RD N E R OT B C AM RD B444 Standlake A4095 PT N B 9 O U Cote B L L ST A little over two miles away is the village of Bampton, U C K L A BAMPTON RD N one of the oldest villages in England, boasting a D R O RIV ER S A T H A ME village shop, Post Office, butcher, and traditional Clanfield D pubs serving good food and real ales, all set around A415 a pretty market square. -

Thames Valley Papists from Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829

Thames Valley Papists From Reformation to Emancipation 1534 - 1829 Tony Hadland Copyright © 1992 & 2004 by Tony Hadland All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without prior permission in writing from the publisher and author. The moral right of Tony Hadland to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 9547547 0 0 First edition published as a hardback by Tony Hadland in 1992. This new edition published in soft cover in April 2004 by The Mapledurham 1997 Trust, Mapledurham HOUSE, Reading, RG4 7TR. Pre-press and design by Tony Hadland E-mail: [email protected] Printed by Antony Rowe Limited, 2 Whittle Drive, Highfield Industrial Estate, Eastbourne, East Sussex, BN23 6QT. E-mail: [email protected] While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, neither the author nor the publisher can be held responsible for any loss or inconvenience arising from errors contained in this work. Feedback from readers on points of accuracy will be welcomed and should be e-mailed to [email protected] or mailed to the author via the publisher. Front cover: Mapledurham House, front elevation. Back cover: Mapledurham House, as seen from the Thames. A high gable end, clad in reflective oyster shells, indicated a safe house for Catholics. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

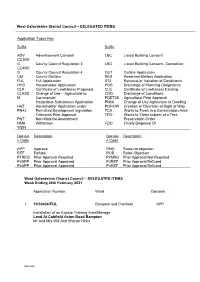

DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Agenda Item No. 5 Week Ending 6th February 2015 Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3REG County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4REG County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Variation of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing Decision Description Decision Description Code Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 14/1357/P/FP Eynsham and Cassington APP Erection of building to create 6 classrooms, 2 science labs and ancillary facilities. Bartholomew School Witney Road Eynsham Bartholomew Academy 2. 14/01997/ADV Witney West APP Erection of internally illuminated sign Oxford House Unit 2 De Havilland Way Windrush Industrial Park 3. 14/02018/FUL Eynsham and Cassington APP Affecting a Conservation Area Erection of new dwelling The Shrubbery 26 High Street Eynsham Dr Max & Joanna Peterson 4. 14/02022/HHD Brize Norton and Shilton APP Form improved vehicular access. Construct detached double garage with games room over. Construct small greenhouse. Erection of boundary fence from new garage to join up with existing fence Yew Tree Cottage 60 Station Road Brize Norton Mr P Granville Agenda Item No. 5, page 1 of 7 5. 14/02106/HHD Ducklington APP Removal of existing garage, lean-to and rear playroom. Erection of single and two-storey extensions to front, side and rear elevations. -

Applications Determined Under Delegated Powers PDF 317 KB

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3RE G County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4RE G County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASS Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions M Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling HAZ Householder Application under POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way PN42 Permitted Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree PNT Non Material Amendment Preservation Order NMA Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of WDN Decisio Description Decisio Description n Code n Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Week Ending 26th February 2021 Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 19/03436/FUL Bampton and Clanfield APP Installation of an Equine Training Area/Manege Land At Cobfield Aston Road Bampton Mr And Mrs Will And Sharon Hicks DELGAT 2. 20/01655/FUL Ducklington REF Erection of four new dwellings and associated works (AMENDED PLANS) Land West Of Glebe Cottage Lew Road Curbridge Mr W Povey, Mr And Mrs C And J Mitchel And Abbeymill Homes L 3. -

The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape, C AD 1500–2000 by Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley

THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000–2000 The Post-Medieval Rural Landscape AD 1500–2000 THE THAMES THROUGH TIME The Archaeology of the Gravel Terraces of the Upper and Middle Thames: The Thames Valley in the Medieval and Post-Medieval Periods AD 1000-2000 The post-medieval rural landscape, c AD 1500–2000 By Anne Dodd and Trevor Rowley INTRODUCTION Compared with previous periods, the study of the post-medieval rural landscape of the Thames Valley has received relatively little attention from archaeologists. Despite the increasing level of fieldwork and excavation across the region, there has been comparatively little synthesis, and the discourse remains tied to historical sources dominated by the Victoria County History series, the Agrarian History of England and Wales volumes, and more recently by the Historic County Atlases (see below). Nonetheless, the Thames Valley has a rich and distinctive regional character that developed tremendously from 1500 onwards. This chapter delves into these past 500 years to review the evidence for settlement and farming. It focusses on how the dominant medieval pattern of villages and open-field agriculture continued initially from the medieval period, through the dramatic changes brought about by Parliamentary enclosure and the Agricultural Revolution, and into the 20th century which witnessed new pressures from expanding urban centres, infrastructure and technology. THE PERIOD 1500–1650 by Anne Dodd Farmers As we have seen above, the late medieval period was one of adjustment to a new reality. -

Oxfordshire Archdeacon's Marriage Bonds

Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by Bride’s Parish Year Groom Parish Bride Parish 1635 Gerrard, Ralph --- Eustace, Bridget --- 1635 Saunders, William Caversham Payne, Judith --- 1635 Lydeat, Christopher Alkerton Micolls, Elizabeth --- 1636 Hilton, Robert Bloxham Cook, Mabell --- 1665 Styles, William Whatley Small, Simmelline --- 1674 Fletcher, Theodore Goddington Merry, Alice --- 1680 Jemmett, John Rotherfield Pepper Todmartin, Anne --- 1682 Foster, Daniel --- Anstey, Frances --- 1682 (Blank), Abraham --- Devinton, Mary --- 1683 Hatherill, Anthony --- Matthews, Jane --- 1684 Davis, Henry --- Gomme, Grace --- 1684 Turtle, John --- Gorroway, Joice --- 1688 Yates, Thos Stokenchurch White, Bridgett --- 1688 Tripp, Thos Chinnor Deane, Alice --- 1688 Putress, Ricd Stokenchurch Smith, Dennis --- 1692 Tanner, Wm Kettilton Hand, Alice --- 1692 Whadcocke, Deverey [?] Burrough, War Carter, Elizth --- 1692 Brotherton, Wm Oxford Hicks, Elizth --- 1694 Harwell, Isaac Islip Dagley, Mary --- 1694 Dutton, John Ibston, Bucks White, Elizth --- 1695 Wilkins, Wm Dadington Whetton, Ann --- 1695 Hanwell, Wm Clifton Hawten, Sarah --- 1696 Stilgoe, James Dadington Lane, Frances --- 1696 Crosse, Ralph Dadington Makepeace, Hannah --- 1696 Coleman, Thos Little Barford Clifford, Denis --- 1696 Colly, Robt Fritwell Kilby, Elizth --- 1696 Jordan, Thos Hayford Merry, Mary --- 1696 Barret, Chas Dadington Hestler, Cathe --- 1696 French, Nathl Dadington Byshop, Mary --- Oxfordshire Archdeacon’s Marriage Bond Index - 1634 - 1849 Sorted by -

Early Medieval Oxfordshire

Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire Sally Crawford and Anne Dodd, December 2007 1. Introduction: nature of the evidence, history of research and the role of material culture Anglo-Saxon Oxfordshire has been extremely well served by archaeological research, not least because of coincidence of Oxfordshire’s diverse underlying geology and the presence of the University of Oxford. Successive generations of geologists at Oxford studied and analysed the landscape of Oxfordshire, and in so doing, laid the foundations for the new discipline of archaeology. As early as 1677, geologist Robert Plot had published his The Natural History of Oxfordshire ; William Smith (1769- 1839), who was born in Churchill, Oxfordshire, determined the law of superposition of strata, and in so doing formulated the principles of stratigraphy used by archaeologists and geologists alike; and William Buckland (1784-1856) conducted experimental archaeology on mammoth bones, and recognised the first human prehistoric skeleton. Antiquarian interest in Oxfordshire lead to a number of significant discoveries: John Akerman and Stephen Stone's researches in the gravels at Standlake recorded Anglo-Saxon graves, and Stone also recognised and plotted cropmarks in his local area from the back of his horse (Akerman and Stone 1858; Stone 1859; Brown 1973). Although Oxford did not have an undergraduate degree in Archaeology until the 1990s, the Oxford University Archaeological Society, originally the Oxford University Brass Rubbing Society, was founded in the 1890s, and was responsible for a large number of small but significant excavations in and around Oxfordshire as well as providing a training ground for many British archaeologists. Pioneering work in aerial photography was carried out on the Oxfordshire gravels by Major Allen in the 1930s, and Edwin Thurlow Leeds, based at the Ashmolean Museum, carried out excavations at Sutton Courtenay, identifying Anglo-Saxon settlement in the 1920s, and at Abingdon, identifying a major early Anglo-Saxon cemetery (Leeds 1923, 1927, 1947; Leeds 1936). -

As a Largely Rural District the Highway Network Plays a Key Role in West Oxfordshire

Highways 8.9 As a largely rural district the highway network plays a key role in West Oxfordshire. The main routes include the A40 Cheltenham to Oxford, the A44 through Woodstock and Chipping Norton, the A361 Swindon to Banbury and the A4260 from Banbury through the eastern part of the District. These are shown on the Key Diagram (Figure 4.1). The provision of a good, reliable and congestion free highway network has a number of benefits including the provision of convenient access to jobs, services and facilities and the potential to unlock and support economic growth. Under the draft Local Plan, the importance of the highway network will continue to be recognised with necessary improvements to be sought where appropriate. This will include the delivery of strategic highway improvements necessary to support growth. 8.10 The A40 is the main east-west transport route with congestion on the section between Witney and Oxford being amongst the most severe transport problems in Oxfordshire and acting as a potential constraint to economic growth. One cause of the congestion is insufficient capacity at the Wolvercote and Cutteslowe roundabouts (outside the District) with the traffic lights and junctions at Eynsham and Cassington (inside the District) adding to the problem. Severe congestion is also experienced on the A44 at the Bladon roundabout, particularly during the morning peak. Further development in the District will put additional pressure on these highly trafficked routes. 8.11 In light of these problems, Oxfordshire County Council developed its ‘Access to Oxford’ project and although Government funding has been withdrawn, the County Council is continuing to seek alternative funding for schemes to improve the northern approaches to Oxford, including where appropriate from new development. -

BBS 129 2015 Feb

ISSN 0960-7870 BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY INFORMATION 129 FEBRUARY 2015 OFFICERS OF THE BRITISH BRICK SOCIETY Chairman Michael Chapman 8 Pinfold Close Tel: 0115-965-2489 NOTTINGHAM NG14 6DP E-mail: [email protected] Honorary Secretary Michael S Oliver 19 Woodcraft Avenue Tel. 020-8954-4976 STANMORE E-mail: [email protected] Middlesex HA7 3PT Honorary Treasurer Graeme Perry 62 Carter Street Tel: 01889-566107 UTTOXETER E-mail: [email protected] Staffordshire ST14 8EU Enquiries Secretary Michael Hammett ARIBA 9 Bailey Close and Liason Officer with the BAA HIGH WYCOMBE Tel: 01494-520299 Buckinghamshire HP 13 6QA E-mail: [email protected] Membership Secretary Dr Anthony A. Preston 11 Harcourt Way (Receives a ll direct subscriptions, £12-00 per annum *) SELSEY, West Sussex PO20 0PF Tel: 01243-607628 Editor of BBS Information David H. Kennett BA, MSc 1 Watery Lane (Receives a ll articles and items fo r BBS Information) SHIPSTON-ON-STOUR Tel: 01608-664039 Warwickshire CV36 4BE E-mail: [email protected] Please note new e-mail address. Printing and Distribution Chris Blanchett Holly Tree House, Secretary 18 Woodlands Road Tel: 01903-717648 LITTLEHAMPTON E-mail: [email protected] West Sussex BN 17 5PP Web Officer Richard Harris Weald and Downland Museum E-mail [email protected] Singleton CHICHESTER West Sussex The society's Auditor is: Adrian Corder-Birch DL Rustlings, Howe Drive E-mail: [email protected] HALSTEAD, Essex CO9 2QL * The annual subscription to the British Brick Society is £12-00 per annum. Telephone numbers and e-mail addresses of members would be helpful for contact purposes, but these will not be included in the Membership List. -

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire

Rawlinson's Proposed History of Oxfordshire By B. J. ENRIGHT INthe English Topographer, published in 1720, Richard Rawlinson described the manuscript and printed sources from which a history of Oxfordshire might be compiled and declared regretfully, ' of this County .. we have as yet no perfect Description.' He hastened to add in that mysteriously weH informed manner which invariably betokened reference to his own activities: But of this County there has been, for some Years past, a Description under Consideration, and great Materials have been collected, many Plates engraved, an actual Survey taken, and Quaeries publish'd and dispers'd over the County, to shew the Nature of the Design, as well to procure Informations from the Gentry and others, which have, in some measure, answer'd the Design, and encouraged the Undertaker to pursue it with all convenient Speed. In this Work will be included the Antiquities of the Town and City of Oxford, which Mr. Anthony d l-Vood, in Page 28 of his second Volume of Athenae Oxonienses, &c. promised, and has since been faithfully transcribed from his Papers, as well as very much enJarg'd and corrected from antient Original Authorities. I At a time when antiquarian studies were rapidly losing their appeal after the halcyon days of the 17th-century,' this attempt to compile a large-scale history of a county which had received so little attention caUs for investigation. In proposing to publish a history of Oxfordshirc at this time, Rawlinson was being far less unrealistic thall might at first appear. For -

Cake & Cockhorse

CAKE & COCKHORSE BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 1979. PRICE 50p. ISSN 0522-0823 BANBURY HISTORICAL SOCIETY President: The Lord Saye and Sele chairman: Alan Donaldson, 2 Church Close, Adderbury, Banbury. Magazine Editor: D. E. M. Fiennes, Woadmill Farm, Broughton, Banbury. Hon. Secretary: Hon. Treasurer: Mrs N.M. Clifton Mr G. de C. Parmiter, Senendone House The Halt, Shenington, Banbury. Hanwell, Banbury.: (Tel. Edge Hill 262) (Tel. Wroxton St. Mary 545) Hm. Membership Secretary: Records Series Editor: Mrs Sarah Gosling, B.A., Dip. Archaeol. J.S. W. Gibson, F.S.A., Banbury Museum, 11 Westgate, Marlborough Road. Chichester PO19 3ET. (Tel: Banbury 2282) (Tel: Chichester 84048) Hon. Archaeological Adviser: J.H. Fearon, B.Sc., Fleece Cottage, Bodicote, Banbury. committee Members: Dr. E. Asser, Mr. J.B. Barbour, Miss C.G. Bloxham, Mrs. G. W. Brinkworth, B.A., David Smith, LL.B, Miss F.M. Stanton Details about the Society’s activities and publications can be found on the inside back cover Our cover illustration is the portrait of George Fox by Chinn from The Story of Quakerism by Elizabeth B. Emmott, London (1908). CAKE & COCKHORSE The Magazine of the Banbury Historical Society. Issued three times a year. Volume 7 Number 9 Summer 1979 Barrie Trinder The Origins of Quakerism in Banbury 2 63 B.K. Lucas Banbury - Trees or Trade ? 270 Dorothy Grimes Dialect in the Banbury Area 2 73 r Annual Report 282 Book Reviews 283 List of Members 281 Annual Accounts 2 92 Our main articles deal with the origins of Quakerism in Banbury and with dialect in the Ranbury area.