Dispute Over the Economics of File Sharing Intensifies - Chronicle.Com Page 1 of 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Diapositiva 1

TRANSFERENCIA O DISTRIBUCIÓN DE ARCHIVOS ENTRE IGUALES (peer-to-peer) Características, Protocolos, Software, Luis Villalta Márquez Configuración Peer-to-peer Una red peer-to-peer, red de pares, red entre iguales, red entre pares o red punto a punto (P2P, por sus siglas en inglés) es una red de computadoras en la que todos o algunos aspectos funcionan sin clientes ni servidores fijos, sino una serie de nodos que se comportan como iguales entre sí. Es decir, actúan simultáneamente como clientes y servidores respecto a los demás nodos de la red. Las redes P2P permiten el intercambio directo de información, en cualquier formato, entre los ordenadores interconectados. Peer-to-peer Normalmente este tipo de redes se implementan como redes superpuestas construidas en la capa de aplicación de redes públicas como Internet. El hecho de que sirvan para compartir e intercambiar información de forma directa entre dos o más usuarios ha propiciado que parte de los usuarios lo utilicen para intercambiar archivos cuyo contenido está sujeto a las leyes de copyright, lo que ha generado una gran polémica entre defensores y detractores de estos sistemas. Las redes peer-to-peer aprovechan, administran y optimizan el uso del ancho de banda de los demás usuarios de la red por medio de la conectividad entre los mismos, y obtienen así más rendimiento en las conexiones y transferencias que con algunos métodos centralizados convencionales, donde una cantidad relativamente pequeña de servidores provee el total del ancho de banda y recursos compartidos para un servicio o aplicación. Peer-to-peer Dichas redes son útiles para diversos propósitos. -

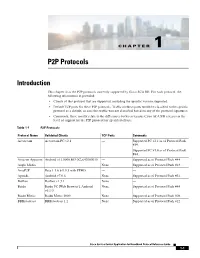

P2P Protocols

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing Authors: Choon Hoong Ding, Sarana Nutanong, and Rajkumar Buyya Grid Computing and Distributed Systems Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Australia (chd, sarana, raj)@cs.mu.oz.au ABSTRACT Peer-to-peer (P2P) technologies have been widely used for content sharing, popularly called “file-swapping” networks. This chapter gives a broad overview of content sharing P2P technologies. It starts with the fundamental concept of P2P computing followed by the analysis of network topologies used in peer-to-peer systems. Next, three milestone peer-to-peer technologies: Napster, Gnutella, and Fasttrack are explored in details, and they are finally concluded with the comparison table in the last section. 1. INTRODUCTION Peer-to-peer (P2P) content sharing has been an astonishingly successful P2P application on the Internet. P2P has gained tremendous public attention from Napster, the system supporting music sharing on the Web. It is a new emerging, interesting research technology and a promising product base. Intel P2P working group gave the definition of P2P as "The sharing of computer resources and services by direct exchange between systems". This thus gives P2P systems two main key characteristics: • Scalability: there is no algorithmic, or technical limitation of the size of the system, e.g. the complexity of the system should be somewhat constant regardless of number of nodes in the system. • Reliability: The malfunction on any given node will not effect the whole system (or maybe even any other nodes). File sharing network like Gnutella is a good example of scalability and reliability. -

Investigating the User Behavior of Peer-To-Peer File Sharing Software

www.ccsenet.org/ijbm International Journal of Business and Management Vol. 6, No. 9; September 2011 Investigating the User Behavior of Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Software Shun-Po Chiu (Corresponding author) PhD candidate, Department of Information Management National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan & Lecture, Department of Information Management Vanung University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Huey-Wen Chou Professor, Department of Information Management National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 26, 2011 Accepted: May 10, 2011 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v6n9p68 Abstract In recent years, peer-to-peer file sharing has been a hotly debated topic in the fields of computer science, the music industry, and the movie industry. The purpose of this research was to examine the user behavior of peer-to-peer file-sharing software. A methodology of naturalistic inquiry that involved qualitative interviews was used to collect data from 21 university students in Taiwan. The results of the study revealed that a substantial amount of P2P file-sharing software is available to users. The main reasons for using P2P file-sharing software are to save money, save time, and to access files that are no longer available in stores. A majority of respondents use P2P file-sharing software to download music, movies, and software, and the respondents generally perceive the use of such software as neither illegal nor unethical. Furthermore, most users are free-riders, which means that they do not contribute files to the sharing process. Keywords: Peer to peer, File sharing, Naturalistic inquiry 1. Introduction In recent years, Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network transmission technology has matured. -

Public Peer-To-Peer Filesharing Networks’ Evaluation

PUBLIC PEER-TO-PEER FILESHARING NETWORKS’ EVALUATION J. Lloret Mauri1, B. Molina Moreno2, C. Palau Salvador3, M. Esteve Domingo4 Department of Communications, Polytechnic University of Valencia Camino Vera s/n, Valencia, Spain [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT • Download speed: some internal P2P network, due to Since the recent appearance of P2P file-sharing networks, its internal behaviour, are optimal for downloading many Internet users have chosen this technology to search files of reduced size. Others, however, use for programs, films, songs, etc. Their number of users is multisplitting mechanisms and permit the download growing every day due to the attractive and interesting from multiple sources, making them suitable for content type that can be found and downloaded over these obtaining larger files. networks. In this article six public architectures are analyzed, Gnutella, FastTrack, Opennap, Edonkey, MP2P These parameters are responsible for an architecture and Soulseek, tracking their evolution during a week in becoming very popular or, on the other hand, terms of connected users, number of files and size of disappearing. The above factors can make a P2P network shared files per hour. The results will be compared and more attractive to users of a specific nation due to the discussed with previous measurements taken a year ago. utilization of a specific language or even social trends [7]. These data can be used to design new network models, to It is also interesting to distinguish between a P2P network calculate their performance or to optimize new network and P2P client, the development of which must not be parameters. -

When Worlds Collide the Intersection of Constructivism, Learning Objects, and Peer-To-Peer Networking Technologies

When Worlds Collide The intersection of constructivism, learning objects, and peer-to-peer networking technologies David Wiley (and hopefully others soon) v1.3, November 6, 2000 The current conception of learning objects There is a vision. A vision in which the creation of instruction can be automated; in which a computer program is capable of inspecting, selecting, and assembling learning objects in order to instantiate an instructional design. And why not? From automobiles to computer processors, humans have succeeded in automating some pretty complex assembly processes. Historically, the success of automation has relied on two factors. The first is an understanding of the assembly process, first discovered and performed by hand, then captured, studied, and expressed in a technology. The second factor is the standardization of component properties. The standardization of component properties creates a marketplace in which many vendors can create components competitively. The broad availability of inexpensive standardized components makes assembly processes easier to express in concrete terms. For example, once standard building construction components such as bricks and two-by-fours were widely available, it became easier to create detailed building plans. The construction metaphor is an apt one for the current discussion, as the current term “learning objects” is borrowed from the 1994 CEdMA working group entitled “Learning Architectures and Learning Objects” (LALO), in which the Architecture is the expression of the construction or assembly process (the blueprint), and the Objects are the standardized components (bricks and boards). But our concern is the facilitation of learning. In our case, the assembly plans are probabilistic instructional design theories and models, prescriptive methods likely to facilitate learning. -

Praktische Untersuchung Und Vergleich Von Gnutella, Kazaa, Edonkey Und Soulseek

Universität Karlsruhe (TH) Praktische Untersuchung und Vergleich von Gnutella, KaZaA, eDonkey und SoulSeek Studienarbeit am Institut für Telematik Prof. Dr.rer.nat. Martina Zitterbart Fakultät für Informatik Universität Karlsruhe (TH) von cand. inform. Christian Wagner Betreuer: Prof. Dr.rer.nat. Martina Zitterbart Dr.rer.nat Thomas Fuhrmann Dipl.-Ing. Kendy Kutzner Tag der Anmeldung: 21. Juli 2003 Tag der Abgabe: 1. Dezember 2003 Institut für Telematik Ich erkläre hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig verfasst und keine anderen als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel verwendet habe. Karlsruhe, den 1. Dezember 2003 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ..................... 1.1 Gliederung der Arbeit....................................................................................... 1 " #to-Peer Netze ............................................................................. & 2.1 Geschichte ........................................................................................................ 3 2.2 Definition.......................................................................................................... 4 2.3 Modelle von P2P-Netzen.................................................................................. 5 2.3.1 P2P-Systeme mit einem zentralen Server................................................. 5 2.3.2 Dezentrale P2P-Systeme........................................................................... 7 2.3.3 Hybride P2P-Systeme.............................................................................. -

Omnix: an Open Peer-To-Peer Middleware Framework

Omnix: An Open Peer-to-Peer Middleware Framework Engineering Topology- and Device-Independent Peer-to-Peer Systems Ph.D. Thesis Roman Kurmanowytsch DISSERTATION Omnix: An Open Peer-to-Peer Middleware Framework Engineering Topology- and Device-Independent Peer-to-Peer Systems ausgefuhrt¨ zum Zwecke der Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der technischen Wissenschaften unter der Leitung von o.Univ.-Prof. Dipl.-Ing. Dr.techn. Mehdi Jazayeri Institut fur¨ Informationssysteme Abteilung fur¨ Verteilte Systeme (E184-1) eingereicht an der Technischen Universitat¨ Wien Fakultat¨ fur¨ Informatik von Univ.-Ass. Dipl.-Ing. Roman Kurmanowytsch [email protected] Matrikelnummer: 9327324 Brunnerstr. 28/12 A-1230 Wien, Osterreich¨ Wien, im Februar 2004 Omnix: An Open Peer-to-Peer Middleware Framework Engineering Topology- and Device-Independent Peer-to-Peer Systems Ph.D. Thesis at Vienna University of Technology submitted by Dipl.-Ing. Roman Kurmanowytsch Distributed Systems Group, Information Systems Institute, Technical University of Vienna Argentinierstr. 8/184-1 A-1040 Vienna, Austria 1st February 2004 c Copyright 2004 by Roman Kurmanowytsch Advisor: o. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Mehdi Jazayeri Second Advisor: a.o. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Gabriele Kotsis Abstract In this thesis, we present Omnix, a Peer-to-Peer (P2P) middleware framework. P2P mid- dleware provides an abstraction between the application and the underlying network by pro- viding higher-level functionality such as distributed P2P searches and direct communication among peers. P2P networks build an overlay network, a network on the network. The central idea of this dissertation is to apply the well-established ISO OSI layered model on P2P middleware systems. A layered P2P architecture helps to identify separate parts of a complex system, allows changes to the system without affecting other layers and makes maintenance easier due to modularization. -

CS 425 / ECE 428 Distributed Systems Fall 2019 Indranil Gupta (Indy) Lecture 7: Peer-To-Peer Systems I

CS 425 / ECE 428 Distributed Systems Fall 2019 Indranil Gupta (Indy) Lecture 7: Peer-to-peer Systems I All slides © IG MP2 Released Today • You will be implementing • Failure detector • Membership protocol • Using concepts you learnt last week! • Stage 2 (of 4) in building a fully-working distributed system from scratch • Stage 3 will be a distributed file system • Stage 4 will be a full distributed system 2 Why Study Peer to Peer Systems? • First distributed systems that seriously focused on scalability with respect to number of nodes • P2P techniques abound in cloud computing systems • Key-value stores (e.g., Cassandra, Riak, Voldemort) use Chord p2p hashing 3 Napster UI 4 A Brief History • [6/99] Shawn Fanning (freshman Northeastern U.) releases Napster online music service • [12/99] RIAA sues Napster, asking $100K per download • [3/00] 25% UWisc traffic Napster, many universities ban it • [00] 60M users • [2/01] US Federal Appeals Court: users violating copyright laws, Napster is abetting this • [9/01] Napster decides to run paid service, pay % to songwriters and music companies • [Today] Napster protocol is open, people free to develop opennap clients and servers http://opennap.sourceforge.net • Gnutella: http://www.limewire.com (deprecated) • Peer to peer working groups: http://p2p.internet2.edu 5 What We Will Study • Widely-deployed P2P Systems (This Lecture) 1. Napster 2. Gnutella 3. Fasttrack (Kazaa, Kazaalite, Grokster) 4. BitTorrent • P2P Systems with Provable Properties (Next Lecture) 1. Chord 2. Pastry 3. Kelips 6 Napster Structure Filename Info about PennyLane.mp3 Beatles, @ Store a directory, i.e., 128.84.92.23:1006 filenames with peer pointers …. -

Broadcasters and the Broadcasters and the Internet

Broadcasters and the Broadcasters and the Internet Internet EBU Members’ Internet Presence Distribution Strategies Online Consumption Trends Social Networking and Video Sharing Communities November 2007 European Broadcasting Union Strategic Information Service (SIS) L’Ancienne-Route 17A CH-1218 Grand-Saconnex Switzerland Phone +41 (0) 22 717 21 11 Fax +41 (0)22 747 40 00 www.ebu.ch/sis European Broadcasting Union l Strategic Information Service Broadcasters and the Internet EBU Members' Internet Presence Distribution Strategies Online Consumption Trends Social Networking and Video Sharing Communities November 2007 The Report Staff This report was produced by the Strategic Information Service of the EBU. Editor: Alexander Shulzycki Production Editor: Anna-Sara Stalvik Principal Researcher: Anna-Sara Stalvik Special appreciation to: Danish Radio and Television (DR) Swedish Television (SVT) Swedish Radio (SR) Cover Design: Philippe Juttens European Broadcasting Union Telephone: +41 22 717 2111 Address: L'Ancienne-Route 17A, 1218 Geneva, Switzerland SIS web-site: www.ebu.ch/director_general/sis.php SIS contact e-mail: [email protected] BROADCASTERS AND THE INTERNET TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 OVERVIEW .............................................................................................................................1 1. The general Internet landscape: usage, websites, advertising ............................................ -

(How to Get Away from the RIAA) Using Newgroups and Hel

The Regulation of Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Networks: Legal Convergence v. Perception Divergence Dr Katerina Sideri, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] The Regulation of Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Networks: Legal Convergence v. Perception Divergence Dr Katerina Sideri Lecturer in Law School of Law, University of Exeter Email: [email protected] and [email protected] Paper prepared for the AHRB Workshop on Network Theme 2 (Globalisation, Convergence and Divergence) Incomplete working paper, do not quote without the author’s permission. 1 The Regulation of Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Networks: Legal Convergence v. Perception Divergence Dr Katerina Sideri, Email: [email protected] and [email protected] A P2P: Regulatory Convergence Millions of people around the globe use peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing networks. However, as these networks function like search engines, allowing looking into files stored in users’ hard discs, many engage in downloading music and movies for free, without compensating copyright holders. Digital technology makes the distribution of multiple perfect copies of copyright material so easy that the entertainment industry has been alerted and brought proceedings before courts in the US, Europe, Canada, Australia and Asia, targeting users and the makers of P2P software for copyright violations, and submitting that it has lost millions as a result of the piracy and counterfeiting taking place in such networks. However, P2P networks are not meant to be primarily designed to promote piracy.1 They play the role of a new distribution channel to promote music or other kinds of art, or even share personal photos with some million other users, thus advancing cultural expression and creativity.