Licensing in the Shadow of Copyright

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cisco SCA BB Protocol Reference Guide

Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide Protocol Pack #60 August 02, 2018 Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. THE SPECIFICATIONS AND INFORMATION REGARDING THE PRODUCTS IN THIS MANUAL ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. ALL STATEMENTS, INFORMATION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS IN THIS MANUAL ARE BELIEVED TO BE ACCURATE BUT ARE PRESENTED WITHOUT WARRANTY OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED. USERS MUST TAKE FULL RESPONSIBILITY FOR THEIR APPLICATION OF ANY PRODUCTS. THE SOFTWARE LICENSE AND LIMITED WARRANTY FOR THE ACCOMPANYING PRODUCT ARE SET FORTH IN THE INFORMATION PACKET THAT SHIPPED WITH THE PRODUCT AND ARE INCORPORATED HEREIN BY THIS REFERENCE. IF YOU ARE UNABLE TO LOCATE THE SOFTWARE LICENSE OR LIMITED WARRANTY, CONTACT YOUR CISCO REPRESENTATIVE FOR A COPY. The Cisco implementation of TCP header compression is an adaptation of a program developed by the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) as part of UCB’s public domain version of the UNIX operating system. All rights reserved. Copyright © 1981, Regents of the University of California. NOTWITHSTANDING ANY OTHER WARRANTY HEREIN, ALL DOCUMENT FILES AND SOFTWARE OF THESE SUPPLIERS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS” WITH ALL FAULTS. CISCO AND THE ABOVE-NAMED SUPPLIERS DISCLAIM ALL WARRANTIES, EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, THOSE OF MERCHANTABILITY, FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE AND NONINFRINGEMENT OR ARISING FROM A COURSE OF DEALING, USAGE, OR TRADE PRACTICE. IN NO EVENT SHALL CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS BE LIABLE FOR ANY INDIRECT, SPECIAL, CONSEQUENTIAL, OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES, INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, LOST PROFITS OR LOSS OR DAMAGE TO DATA ARISING OUT OF THE USE OR INABILITY TO USE THIS MANUAL, EVEN IF CISCO OR ITS SUPPLIERS HAVE BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGES. -

Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers Reach Global Theaters That They Overlap the Domestic USA Blu-Ray Release

Moviegoers - or perhaps more accurately, lovers of cinema - are frustrated. Their frustrations begin with the discrepancies in film release strategies and timing. For example, audiences that saw Quentin Tarantino’s1 2 Django Unchained in the United States enjoyed its opening on Christmas day 2012; however, in Europe and other markets, viewers could not pay to see the movie until after the 17th of January 2013. Three weeks may not seem like a lot, but some movies can take months to reach an international audience. Some take so long to Piratez Are Just Disgruntled Consumers reach global theaters that they overlap the domestic USA Blu-Ray release. This delay can seem like an eternity for ultiscreen is at the top of the entertainment a desperate fan. This frustrated enthusiasm, combined industry’s agenda for delivering digital video. This with a lack of timely availability, leads to the feeling of M is discussed in the context of four main screens: being treated as a second class citizen - and may lead TVs, PCs, tablets and mobile phones. The premise being the over-anxious fan to engage in piracy. that multiscreen enables portability, usability and flexibility for consumers. But, there is a fifth screen which There has been some evolution in this practice, with is often overlooked – the cornerstone of the certain films being released simultaneously to a domestic and global audience. For example, Avatar3 was released entertainment industry - cinema. This digital video th th ecosystem is not complete without including cinema, and in theaters on the 10 and 17 of December in most it certainly should be part of the multiscreen discussion. -

Simulacijski Alati I Njihova Ograničenja Pri Analizi I Unapređenju Rada Mreža Istovrsnih Entiteta

SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET ORGANIZACIJE I INFORMATIKE VARAŽDIN Tedo Vrbanec SIMULACIJSKI ALATI I NJIHOVA OGRANIČENJA PRI ANALIZI I UNAPREĐENJU RADA MREŽA ISTOVRSNIH ENTITETA MAGISTARSKI RAD Varaždin, 2010. PODACI O MAGISTARSKOM RADU I. AUTOR Ime i prezime Tedo Vrbanec Datum i mjesto rođenja 7. travanj 1969., Čakovec Naziv fakulteta i datum diplomiranja Fakultet organizacije i informatike, 10. listopad 2001. Sadašnje zaposlenje Učiteljski fakultet Zagreb – Odsjek u Čakovcu II. MAGISTARSKI RAD Simulacijski alati i njihova ograničenja pri analizi i Naslov unapređenju rada mreža istovrsnih entiteta Broj stranica, slika, tablica, priloga, XIV + 181 + XXXVIII stranica, 53 slike, 18 tablica, 3 bibliografskih podataka priloga, 288 bibliografskih podataka Znanstveno područje, smjer i disciplina iz koje Područje: Informacijske znanosti je postignut akademski stupanj Smjer: Informacijski sustavi Mentor Prof. dr. sc. Željko Hutinski Sumentor Prof. dr. sc. Vesna Dušak Fakultet na kojem je rad obranjen Fakultet organizacije i informatike Varaždin Oznaka i redni broj rada III. OCJENA I OBRANA Datum prihvaćanja teme od Znanstveno- 17. lipanj 2008. nastavnog vijeća Datum predaje rada 9. travanj 2010. Datum sjednice ZNV-a na kojoj je prihvaćena 18. svibanj 2010. pozitivna ocjena rada Prof. dr. sc. Neven Vrček, predsjednik Sastav Povjerenstva koje je rad ocijenilo Prof. dr. sc. Željko Hutinski, mentor Prof. dr. sc. Vesna Dušak, sumentor Datum obrane rada 1. lipanj 2010. Prof. dr. sc. Neven Vrček, predsjednik Sastav Povjerenstva pred kojim je rad obranjen Prof. dr. sc. Željko Hutinski, mentor Prof. dr. sc. Vesna Dušak, sumentor Datum promocije SVEUČILIŠTE U ZAGREBU FAKULTET ORGANIZACIJE I INFORMATIKE VARAŽDIN POSLIJEDIPLOMSKI ZNANSTVENI STUDIJ INFORMACIJSKIH ZNANOSTI SMJER STUDIJA: INFORMACIJSKI SUSTAVI Tedo Vrbanec Broj indeksa: P-802/2001 SIMULACIJSKI ALATI I NJIHOVA OGRANIČENJA PRI ANALIZI I UNAPREĐENJU RADA MREŽA ISTOVRSNIH ENTITETA MAGISTARSKI RAD Mentor: Prof. -

Diapositiva 1

TRANSFERENCIA O DISTRIBUCIÓN DE ARCHIVOS ENTRE IGUALES (peer-to-peer) Características, Protocolos, Software, Luis Villalta Márquez Configuración Peer-to-peer Una red peer-to-peer, red de pares, red entre iguales, red entre pares o red punto a punto (P2P, por sus siglas en inglés) es una red de computadoras en la que todos o algunos aspectos funcionan sin clientes ni servidores fijos, sino una serie de nodos que se comportan como iguales entre sí. Es decir, actúan simultáneamente como clientes y servidores respecto a los demás nodos de la red. Las redes P2P permiten el intercambio directo de información, en cualquier formato, entre los ordenadores interconectados. Peer-to-peer Normalmente este tipo de redes se implementan como redes superpuestas construidas en la capa de aplicación de redes públicas como Internet. El hecho de que sirvan para compartir e intercambiar información de forma directa entre dos o más usuarios ha propiciado que parte de los usuarios lo utilicen para intercambiar archivos cuyo contenido está sujeto a las leyes de copyright, lo que ha generado una gran polémica entre defensores y detractores de estos sistemas. Las redes peer-to-peer aprovechan, administran y optimizan el uso del ancho de banda de los demás usuarios de la red por medio de la conectividad entre los mismos, y obtienen así más rendimiento en las conexiones y transferencias que con algunos métodos centralizados convencionales, donde una cantidad relativamente pequeña de servidores provee el total del ancho de banda y recursos compartidos para un servicio o aplicación. Peer-to-peer Dichas redes son útiles para diversos propósitos. -

Psichogios.Pdf

1 ΠΑΝΕΠΙΣΤΗΜΙΟ ΠΕΙΡΑΙΩΣ Τμήμα Ψηφιακών Συστημάτων «Διαχείριση κατανεμημένου πολυμεσικού περιεχομένου με χρήση υπηρεσιοστρεφών αρχιτεκτονικών » ΨΥΧΟΓΥΙΟΣ ΕΥΣΤΑΘΙΟΣ Η εργασία υποβάλλεται για την μερική κάλυψη των απαιτήσεων με στόχο την απόκτηση του Μεταπτυχιακού Διπλώματος Σπουδών στα Ψηφιακά Συστήματα του Πανεπιστήμιο Πειραιώς 2 ΠΙΝΑΚΑΣ ΠΕΡΙΕΧΟΜΕΝΩΝ ΠΙΝΑΚΑΣ ΠΕΡΙΕΧΟΜΕΝΩΝ ............................................................................... 2 ΠΕΡΙΛΗΨΗ ............................................................................................................. 4 ΚΑΤΑΛΟΓΟΣ ΣΧΗΜΑΤΩΝ .................................................................................. 5 ΕΙΣΑΓΩΓΗ .............................................................................................................. 6 ΜΕΡΟΣ ΠΡΩΤΟ ..................................................................................................... 7 0 ΚΕΦΑΛΑΙΟ 1 - ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ ........................................ 7 ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ – ΕΙΣΑΓΩΓΗ ........................................... 7 ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ – ΠΛΕΟΝΕΚΤΗΜΑΤΑ ............................. 9 ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ – ΠΑΡΑΔΕΙΓΜΑΤΑ................................ 10 ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ – ΤΙ ΑΛΛΑΖΕΙ; ....................................... 11 ΥΠΗΡΕΣΙΕΣ ΠΑΓΚΟΣΜΙΟΥ ΙΣΤΟΥ – TO ΜΕΛΛΟΝ ΤΟΥΣ ΣΤΗΝ ΕΛΛΑΔΑ .. 12 ΤΕΧΝΙΚΑ ΧΑΡΑΚΤΗΡΙΣΤΙΚΑ – ΟΡΙΣΜΟΣ ....................................................ΠΕΙΡΑΙΑ 14 ΤΕΧΝΙΚΑ ΧΑΡΑΚΤΗΡΙΣΤΙΚΑ – ΜΟΝΤΕΛΟ .................................................. -

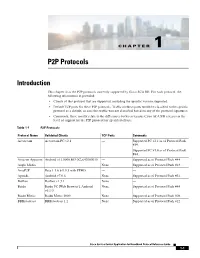

P2P Protocols

CHAPTER 1 P2P Protocols Introduction This chapter lists the P2P protocols currently supported by Cisco SCA BB. For each protocol, the following information is provided: • Clients of this protocol that are supported, including the specific version supported. • Default TCP ports for these P2P protocols. Traffic on these ports would be classified to the specific protocol as a default, in case this traffic was not classified based on any of the protocol signatures. • Comments; these mostly relate to the differences between various Cisco SCA BB releases in the level of support for the P2P protocol for specified clients. Table 1-1 P2P Protocols Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments Acestream Acestream PC v2.1 — Supported PC v2.1 as of Protocol Pack #39. Supported PC v3.0 as of Protocol Pack #44. Amazon Appstore Android v12.0000.803.0C_642000010 — Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. Angle Media — None Supported as of Protocol Pack #13. AntsP2P Beta 1.5.6 b 0.9.3 with PP#05 — — Aptoide Android v7.0.6 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #52. BaiBao BaiBao v1.3.1 None — Baidu Baidu PC [Web Browser], Android None Supported as of Protocol Pack #44. v6.1.0 Baidu Movie Baidu Movie 2000 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #08. BBBroadcast BBBroadcast 1.2 None Supported as of Protocol Pack #12. Cisco Service Control Application for Broadband Protocol Reference Guide 1-1 Chapter 1 P2P Protocols Introduction Table 1-1 P2P Protocols (continued) Protocol Name Validated Clients TCP Ports Comments BitTorrent BitTorrent v4.0.1 6881-6889, 6969 Supported Bittorrent Sync as of PP#38 Android v-1.1.37, iOS v-1.1.118 ans PC exeem v0.23 v-1.1.27. -

Pledge of Compliance of the Information Security Policy of Nagoya University

For submission Pledge of Compliance of the Information Security Policy of Nagoya University To the Director of Information and Communications Headquarters 1. As a member of the academic community of Nagoya University, I will carefully read the following two documents and hereby pledge to comply with the rules, regulations and guidelines specified therein. a. The Information Security Policy of Nagoya University (*1) b. The Network Usage Guidelines (User Information) of Nagoya University (*2) 2. I promise to take the “e-Learning Training Course on Information Security” (*3) within one month after enrollment. Examinee's number Date: School / Graduate School: Department: Name: Signature: Notice: Users who violate the Information Security Policy of Nagoya University and/or the Network Usage Guidelines (User Information) of Nagoya University may be subject to disciplinary action according to the Nagoya University General Rules, the Nagoya University Student Discipline Rules, etc. Downloading illegally distributed music and/or movie files is an infringement of copyright law. Those who download files illegally will be liable for compensation damages. Nagoya University will prohibit any illegal downloading of files through its computers and/or network. Nagoya University prohibits the use of file sharing software such as Winny, WinMX, Share, Gnutella (Cabos, LimeWire, Shareaza, etc.) and Xunlei. * If the use of said software is required for education or research purposes, prior approval by the Information and Communications Headquarters is mandatory. If users fail to take the “e-Learning Training Course on Information Security” within one month after enrollment or if they do not successfully complete the course, their access to the Nagoya University Portal, Nagoya University Mail, the Information Media System, and the Wireless LAN (NUWNET) will be suspended. -

(Camara)\Thomas-Rasset PFC.Wpd

NO. In the Supreme Court of the United States JAMMIE THOMAS–RASSET, Petitioner, v. CAPITOL RECORDS INC. et al., Respondents. On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI K.A.D. CAMARA Counsel of Record CHARLES R. NESSON CAMARA & SIBLEY LLP 2800 Post Oak Blvd., Suite 5220 Houston, Texas 77056 (713) 966-6789 [email protected] Attorneys for Petitioner December 10, 2012 Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i QUESTION PRESENTED Is there any constitutional limit to the statutory damages that can be imposed for downloading music online? ii PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING The parties to the proceeding are Jammie Thomas–Rasset, Petitioner; Capitol Records Inc., Sony BMG Music Entertainment, Arista Records LLC, Interscope Records, Warner Bros. Records Inc., and UMG Recordings Inc., Respondents; United States of America, Intervenor; Electronic Frontier Foundation, Internet Archive, American Library Association, Association of Research Libraries, Association of College and Research Libraries, and Public Knowledge, amici on behalf of Petitioner; and Motion Picture Association of America Inc., amicus on behalf of Respondents. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS QUESTION PRESENTED.................... i PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING ............. ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... v PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI ...... 1 OPINIONS BELOW ......................... 1 JURISDICTION ............................ 1 CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS INVOLVED................. 1 STATEMENT .............................. 3 REASONS FOR GRANTING THE PETITION . 21 CONCLUSION ............................ 25 APPENDIX Appendix A Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit (September 11, 2012) ..........App. 1 Appendix BMemorandum of Law & Order in the United States District Court District of Minnesota (July 22, 2011) ..............App. -

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing

Title: P2P Networks for Content Sharing Authors: Choon Hoong Ding, Sarana Nutanong, and Rajkumar Buyya Grid Computing and Distributed Systems Laboratory, Department of Computer Science and Software Engineering, The University of Melbourne, Australia (chd, sarana, raj)@cs.mu.oz.au ABSTRACT Peer-to-peer (P2P) technologies have been widely used for content sharing, popularly called “file-swapping” networks. This chapter gives a broad overview of content sharing P2P technologies. It starts with the fundamental concept of P2P computing followed by the analysis of network topologies used in peer-to-peer systems. Next, three milestone peer-to-peer technologies: Napster, Gnutella, and Fasttrack are explored in details, and they are finally concluded with the comparison table in the last section. 1. INTRODUCTION Peer-to-peer (P2P) content sharing has been an astonishingly successful P2P application on the Internet. P2P has gained tremendous public attention from Napster, the system supporting music sharing on the Web. It is a new emerging, interesting research technology and a promising product base. Intel P2P working group gave the definition of P2P as "The sharing of computer resources and services by direct exchange between systems". This thus gives P2P systems two main key characteristics: • Scalability: there is no algorithmic, or technical limitation of the size of the system, e.g. the complexity of the system should be somewhat constant regardless of number of nodes in the system. • Reliability: The malfunction on any given node will not effect the whole system (or maybe even any other nodes). File sharing network like Gnutella is a good example of scalability and reliability. -

Investigating the User Behavior of Peer-To-Peer File Sharing Software

www.ccsenet.org/ijbm International Journal of Business and Management Vol. 6, No. 9; September 2011 Investigating the User Behavior of Peer-to-Peer File Sharing Software Shun-Po Chiu (Corresponding author) PhD candidate, Department of Information Management National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan & Lecture, Department of Information Management Vanung University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Huey-Wen Chou Professor, Department of Information Management National Central University, Jhongli, Taoyuan, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] Received: March 26, 2011 Accepted: May 10, 2011 doi:10.5539/ijbm.v6n9p68 Abstract In recent years, peer-to-peer file sharing has been a hotly debated topic in the fields of computer science, the music industry, and the movie industry. The purpose of this research was to examine the user behavior of peer-to-peer file-sharing software. A methodology of naturalistic inquiry that involved qualitative interviews was used to collect data from 21 university students in Taiwan. The results of the study revealed that a substantial amount of P2P file-sharing software is available to users. The main reasons for using P2P file-sharing software are to save money, save time, and to access files that are no longer available in stores. A majority of respondents use P2P file-sharing software to download music, movies, and software, and the respondents generally perceive the use of such software as neither illegal nor unethical. Furthermore, most users are free-riders, which means that they do not contribute files to the sharing process. Keywords: Peer to peer, File sharing, Naturalistic inquiry 1. Introduction In recent years, Peer-to-Peer (P2P) network transmission technology has matured. -

Instructions for Using Your PC ǍʻĒˊ Ƽ͔ūś

Instructions for using your PC ǍʻĒˊ ƽ͔ūś Be careful with computer viruses !!! Be careful of sending ᡅĽ/ͼ͛ᩥਜ਼ƶ҉ɦϹ࿕ZPǎ Ǖễƅ͟¦ᰈ Make sure to install anti-virus software in your PC personal profile and ᡅƽញƼɦḳâ 5☦ՈǍʻPǎᡅ !!! information !!! It is very dangerous !!! ΚTẝ«ŵ┭ՈT Stop violation of copyright concerning illegal acts of ơųጛňƿՈ☢ͩ ⚷<ǕOᜐ&« transmitting music and ₑᡅՈϔǒ]ᡅ others through the Don’t forget to backup ඡȭ]dzÑՈ Internet !!! important data !!! Ȥᩴ̣é If another person looks in at your E-mail, it’s a big ὲâΞȘᝯɣr problem !!! Don’t install software in dz]ǣrPǎᡅ ]ᡅîPéḳâ╓ ͛ƽញ4̶ᾬϹ࿕ ۅTake care of keeping your some other PCs without ˊΙǺ password !!! permission !!! ₐ Stop sending the followings !!! ŌՈϹوInformation against public order and Somebody targets on your PC for Pǎ]ᡅǕễạǑ͘͝ࢭÛ ΞȘƅ¦Ƿń morals illegal access !!! Ոƅ͟ǻᢊ᫁ĐՈ ࿕Ϭ⓶̗ʵ£࿁îƷljĈ Information about discrimination, Shut out those attacks with firewall untruth and bad reputation against a !!! Ǎʻ ᰻ǡT person ᤘἌ᭔ ᆘჍഀ ጠᅼૐᾑ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞęɪᬡᬡǰɟ ᆘȐೈ ᾑ ጠᅼ3ظ ᤘἌ᭔ ǰɟᯓۀ᭞ᮞᮐᮧ᭪᭑ᮖ᭤ᬞᬢ ഄᅤ Έʡȩîᬡ͒ͮᬢـ ᅼܘᆘȐೈ ǸᆜሹظᤘἌ᭔ ཬᴔ ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞᬢŽᬍ᭑ᮖ᭤̛ɏ᭨ᮀ᭳ᭅ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘Π ؼ˨ഀ ୈὼ$ ഄጵ↬3L ʍ୰ᬞᯓ ᄨῼ33 Ȋථᬚᬌᬻᯓ ഄ˽ ઁǢᬝຨϙଙͮـᅰჴڹެ ሤᆵͨ˜Ɍ ጵႸᾀ żᆘ᭔ ᬝᬜΪ̎UઁɃᬢ ࡶ୰ᬝ᭲ᮧ᭪ᬢ ᄨؼᾭᄨ ᾑ ٕᅨ ΰ̛ᬞ᭫ᮌᯓ ᭻᭮᭚᭮ᮂᭅ ሬČ ཬȴ3 ᾘɤɟ3 Ƌᬿᬍᬞᯓ ᬿᬒᬼۏąഄᅼ Ѹᆠᅨ ᮌᮧᮖᭅ ᛴܠ ఼ ᆬð3 ᤘἌ᭔ ƂŬᯓ ᭨ᮀ᭳᭑᭒ᭅƖ̳ᬞ ĩᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᬞٴ ரἨ᳜ᄌ࿘ ᭼᭤ᮚᮧ᭴ᬡɼǂᬢ ڹެ ᵌೈჰ˨ ˜ϐ ᛄሤ↬3 ᆜೈᯌ ϤᏤ ᬊᬖᬽᬊᬻᯓ ᮞ᭤᭳ᮧᮖᬊᬝᬚ ሬČʀ ͌ǜ ąഄᅼ ΰ̛ᬞ ޅᬝᬒᬡ᭼᭨᭞ᮞᭅ ᤘἌ᭔Π ͬϐʼ ᆬð3 ʏͦᬞɃᬌᬾȩî ēᬖᬙᬾᯓ ܘˑˑᏬୀΠ ᄨؼὼ ሹ ߍɋᬞᬒᬾȩî ᮀᭌ᭑᭔ᮧᮖwƫᬚފᴰᆘ࿘ჸ $±ᅠʀ =Ė ܘČٍᅨ ᙌۨ5ࡨٍὼ ሹ ഄϤᏤ ᤘἌ᭔ ኩ˰Π3 ᬢ͒ͮᬊᬝᯓ ᭢ᮎ᭮᭳᭑᭳ᬊᬻᯓـ ʧʧ¥¥ᬚᬚP2PP2P᭨᭨ᮀᮀ᭳᭳᭑᭑᭒᭒ᬢᬢ DODO NOTNOT useuse P2PP2P softwaresoftware ̦̦ɪɪᬚᬚᬀᬀᬱᬱᬎᬎᭆᭆᯓᯓ inin campuscampus networknetwork !!!! Z ʧ¥᭸᭮᭳ᮚᮧ᭚ᬞᬄᬾͮᬢȴƏΜˉ᭢᭤᭱ Z All communications in our campus network are ᬈᬿᬙᬱᬌʧ¥ᬚP2P᭨ᮀ always monitored automatically. -

Internet-Operaattoreihin Kohdistetut Tekijänoikeudelliset Estomääräykset Erityisesti Vertaisverkkopalvelun Osalta

Pekka Savola INTERNET-OPERAATTOREIHIN KOHDISTETUT TEKIJÄNOIKEUDELLISET ESTOMÄÄRÄYKSET ERITYISESTI VERTAISVERKKOPALVELUN OSALTA Lisensiaatintutkimus, joka on jätetty opinnäytteenä tarkastettavaksi tekniikan lisensiaatin tutkintoa varten Espoossa, 21. marraskuuta 2012. Vastuuprofessori Raimo Kantola Ohjaaja FT, OTK Ville Oksanen AALTO-YLIOPISTO LISENSIAATINTUTKIMUKSEN TIIVISTELMÄ TEKNIIKAN KORKEAKOULUT PL 11000, 00076 AALTO http://www.aalto.fi Tekijä: Pekka Savola Työn nimi: Internet-operaattoreihin kohdistetut tekijänoikeudelliset estomääräykset erityisesti vertaisverkkopalvelun osalta Korkeakoulu: Sähkötekniikan korkeakoulu Laitos: Tietoliikenne- ja tietoverkkotekniikka Tutkimusala: Tietoverkkotekniikka Koodi: S041Z Työn ohjaaja(t): FT, OTK Ville Oksanen Työn vastuuprofessori: Raimo Kantola Työn ulkopuolinen tarkastaja(t): Professori, OTT Niklas Bruun Tiivistelmä: Tarkastelen työssäni Internet-yhteydentarjoajiin (operaattoreihin) kohdistettuja tekijänoikeudellisia estomääräyksiä erityisesti vertaisverkkopalvelun osalta sekä tekniseltä että oikeudelliselta kannalta. Tarkastelen erityisesti The Pirate Bay -palvelusta herääviä kysymyksiä. Esitän aluksi yleiskatsauksen muistakin kuin tekijänoikeudellisista säännöksistä ja tarkastelen laajaa ennakollisen ja jälkikäteisen puuttumisen keinojen kirjoa. Tarkastelen teknisiä estomenetelmiä ja estojen kierrettävyyttä ja tehokkuutta. Keskeisimpiä estotapoina esittelen IP-, DNS- ja URL-estot. URL-eston toteuttaminen kaksivaiheisena menetelmänä olisi järjestelmistä joustavin, mutta siihen liittyvät