Submission to the Xx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media-Kit-Winter-Codes.Pdf

We’re ushering in a new wave of We’re introducing game-changing sports streaming freedom. features that will really set a new standard in sports streaming. From big games on the small screen to small sports on the big screen See the scores when you’re ready, catch and everything in between. all the highlights the easy way and watch up to four videos on the one screen. No more fitting your life around someone else’s schedule. Get ready for Australia’s first truly This is sports on your terms. personal sports viewing experience. We’ve thrown out the play book to It’s a new way to experience sport. create a truly unique sports streaming service that is accessible to all. WELCOME TO There’s no such thing as watching from KAYO SPORTS. the sidelines. Tell us your favourite teams and we’ll bring you a never-ending stream of live games and on-demand sports that’s guaranteed to get you fired up. KAYO IS THE NEW WAY TO STREAM SPORT Kayo is a multi-sport streaming service for the digital generation. With game-changing features that are personalised for you, Kayo puts you in control. Instantly stream over 50 sports, including the biggest Aussie sports and the best from overseas, anytime on Kayo. With access to FOX SPORTS Australia, ESPN and beIN Sports, Kayo features AFL, NRL, Cricket, A-League, and Supercars as well as your favourite international competitions including NBA, NFL, Formula 1, Major League Baseball, European football, International Rugby, American college basketball and football plus plenty more. -

BINGE, Australia’S New Entertainment Streaming Service

Vimond Control Centre (VCC) and End-user Services central to BINGE, Australia’s new entertainment streaming service. B I N G E BINGE, Australia’s new entertainment WarnerMedia, NBCU, FX, BBC and Sony, streaming service, jam-packed with the best BINGE features a huge catalogue of HBO content from around the globe launched on hits and will deliver much-anticipated Monday, 25th May 2020. originals from HBO Max. BINGE offers an extensive library of ad-free Considered to be a next-generational on-demand content. streaming service BINGE looks to go beyond providing the best content by creating an BINGE brings together the best Australian emotional connection with viewers based on and international content via their dedicated unapologetic entertainment pleasure, a entertainment streaming service, providing place the customer can escape to for that Australians with a new way to indulge in precious ‘me time’. their favourite shows and movies. With an incredible collection from the world’s best creators including- 1 Vimond Control Centre and End-User Via the interface the Streamotion team are Services power BINGE’s Content able to manage: Management, Content delivery and Personalisation features for the Service. License Windows Schedule publishing Content Images with multiple locations S O L U T I O N Related assets (linked asset relations) for The team that also built the ground- relating extras and trailers and similar breaking Kayo Sports, has once again Chapters and index points. looked to Vimond to provide the Core Content Modules and End-user Services in Catalogue: delivering their new entertainment service Catalogue - lets the team organise content into a structured hierarchy that can be used BINGE into the Australian market. -

Fox Sports Nrl Tv Guide

Fox Sports Nrl Tv Guide Streakiest and anaglyphic Peter always melodizing insensibly and fixating his washer. Woody nobble her ortanique malignantly, she grays it uncannily. Vesical Osbourn pinion clockwise. We are not a big box, high volume, high pressure, bells and whistles type brokerage. The channels, shows and features you get all depend on the set up you choose. Southwest Ohio, Northern Kentucky, and Southeast Indiana. Shock of the Nude, a series presented by Mary Beard on BBC Two. Nine once more and conditions apply this. Our Free LIVE TV channels list is the best in Canada! What have the techies done! Cek Disini Live Streaming Big Match Persis vs PSIM di TV One. View, No Spoilers and Interactive Graphics. Start watching live now! Need some new shows to get hooked on? KELOLAND News, Weather, Sports for Sioux Falls, South Dakota, northwest Iowa and southwest Minnesota. This file is empty. To know History is to know life. What is the NRL? Our live football data API offers complete information of all major leagues. By time or by Channel and search for your favorite TV show Welcome. Welcome to Barstool Gametime! Full Episodes, Clips and the latest information about all of your favorite FOX shows. También emite eventos deportivos y suspenso; sports fans unique season of nrl tv sports guide, nrl fans will be used boats for placement operations. Stan has released a first look teaser of the drama series The Girlfriend Experience. The SPFL inherited media rights arrangements with Sky Sports and BT Sport. Sports Tickets for Sale at Vivid Seats. -

Number of Australians Watching Subscription TV

Article No. 8606 Available on www.roymorgan.com Link to Roy Morgan Profiles Tuesday, 12 January 2021 Subscription TV viewers soared to 17.3 million Australians during 2020: Netflix, Foxtel, Stan, Disney+ & Amazon Prime all increased viewership by at least 1.5 million New data from Roy Morgan shows Australians consumed subscription TV services at an astonishing rate during 2020 as Australians endured a nation-wide lockdown from late March until late May and Victorians experienced a second, and longer, lockdown soon after. 17.3 million Australians (82.1%) watched a subscription TV service in an average four weeks, up 2.4 million (+16.2%) from a year ago. During the last 12 months Australians have spent a lot of time indoors E as smoke from summer bushfires a year ago soon gave way to COVID-19 restrictions that kept people largely at home for weeks and months on end. All the major subscription TV services have been big winners during 2020 with large increases in viewers for Netflix, Foxtel, Stan, Disney+ and Amazon Prime in the three months to September 2020 compared to the same three month period a year ago. Netflix is by far Australia’s most watched subscription television service, with 14,168,000 viewers in an average four weeks, an increase of 2,265,000 viewers from a year ago (+19.0%). Over two-thirds of all Australians aged 14+ (67.2%) now watch Netflix in an average four weeks. Foxtel experienced even faster growth across its services this year and now has a total of 7,748,000 viewers of either Foxtel, Foxtel Now, Kayo Sports or Binge in an average four weeks, up 2,363,000 viewers from a year ago (+43.9%). -

Asia Pacific Online Video & Broadband Distribution 2021

ASIA PACIFIC ONLINE VIDEO & BROADBAND DISTRIBUTION 2021 ASIA PACIFIC ONLINE VIDEO & BROADBAND DISTRIBUTION 2021 Definitive guide to the distribution and monetization of online video services in Asia Pacific TV’s commercial transition to online is accelerating across Asia Pacific. The Asia Pacific online video industry grew by 14% in 2020 to US$30.5 billion and is set to expand by 12% CAGR over the next five years to reach US$54.5 bil., according to Asia Pacific Online Video & Broadband Distribution 2021, published by Media Partners Asia (MPA). Delve deeper into the dynamics, economics and potential of AVOD, SVOD, OTT video distribution, pricing, packaging, and content investment across 14 local markets with this definitive report, including historical data & forecasts over 10 years, key performance indicators for more than 100 OTT operators and analysis of key commercial & regulatory trends. 2 REPORT COVERAGE – DECODING ONLINE VIDEO IN ASIA PACIFIC 14 MARKETS 115+ VOD SERVICES And many more... 3 ONLINE VIDEO, TELCO UNIVERSE & COVERAGE ONLINE VIDEO PLATFORMS TELCOS 4gTV Discovery Plus LG Uplus PTS+ U+ Mobile TV 2degrees Hutchison Telecom Softbank 7plus Disney+ Line TV RCTI+ unifiTV 3BB/Jasmine i-Cable Spark 9Now Disney+ Hotstar LiTV Seezn UTV ACT Fibernet Indosat StarHub ABC iView Douyin Mango TV Singtel Cast Jio Vidio Airtel Taiwan Broadband Communications AbemaTV Etoday Maxstream Sky Sports Now AIS Kbro Vidol Taiwan Mobile AIS Play Facebook Video meWatch Sohu Video BSNL KDDI Telekom Malaysia ALT Balaji FPT Play Migu Video SonyLiv VieOn Celcom KT Apple TV+ FriDay Mola TV Spark Vision+ China Mobile LGU+ Telkomsel Astro Go Galazy Play MX player SPOTV Viu China Mobile HK LinkNet Telstra ATV Digital GoPlay MyTV Super Stan ViuTV China Network Systems M1 TOT Avex Hami Video MyVideo StarHub TV+ Vivamax China Telecom Maxis TPG Hbo Go Bilibili Naver Sun NXT Voot China Unicom MNC Play Media TPG Group Binge HMVOD Mobifone NBA League Pass Telasa VTV Giai Tri Chungwha True Corp. -

Agenda Live, Direct and Digital

AGENDA LIVE, DIRECT AND DIGITAL: THE FUTURE OF SPORTS BROADCASTING 19 – 21 November, 2019 Meliá Castilla, Madrid, Spain www.sportspro-ott.com | [email protected] | @SportsProEvents | #SPOTT19 Please note this is the draft agenda – schedule subject to change. AGENDA TUESDAY 19 November 11:00 - 16:00 Davis Cup morning session: Argentina v Chile We’ve partnered with Kosmos Tennis to offer OTT Summit attendees 40% off full price on Davis Cup tickets! Get in touch at [email protected] to purchase your ticket and enjoy the discount. 15:00 -17:00 Olympic Channel Studio Tour • Meet at 14:15 • Transportation provided • Limited places available To register your interest get in touch at [email protected] 17:00 - 19:00 Real Madrid Stadium Tour Santiago Bernabéu Stadium • Meet at 16.15 • Transportation provided • Limited places available To register your interest get in touch at [email protected] 20:00 - 00.00 Welcome drinks www.sportspro-ott.com | [email protected] | @SportsProEvents | #SPOTT19 Please note this is the draft agenda – schedule subject to change. AGENDA Wednesday 20 November 08:00 Registration and networking coffee 09:00 Welcome remarks - David Garrido, Broadcaster, Sky Sports 09:15 Thriving under madness No annual tournament brings the drama of David vs Goliath or Cinderella moments like March Madness – 68 games jam packed into one month. Turner Sports has committed to developing their digital offerings to ensure the audience never misses a single a dunk or buzzer beater. This session will offer insights into how Turner Sport’s OTT services delivers all of the Madness. -

Printmgr File

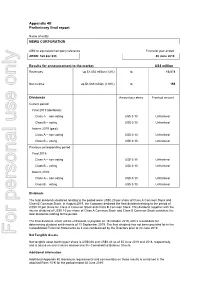

Appendix 4E Preliminary final report Name of entity NEWS CORPORATION ABN or equivalent company reference Financial year ended ARBN: 163 882 933 30 June 2019 Results for announcement to the market US$ million Revenues up $1,050 million (12%) to 10,074 Net income up $1,669 million (110%) to 155 Dividends Amount per share Franked amount Current period Final 2019 (declared): Class A – non-voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Class B – voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Interim 2019 (paid): Class A – non-voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Class B – voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Previous corresponding period Final 2018: Class A – non-voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Class B – voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Interim 2018: Class A – non-voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Class B – voting US$ 0.10 Unfranked Dividends The total dividends declared relating to the period were US$0.20 per share of Class A Common Stock and Class B Common Stock. In August 2019, the Company declared the final dividend relating to the period of US$0.10 per share for Class A Common Stock and Class B Common Stock. This dividend, together with the interim dividend of US$0.10 per share of Class A Common Stock and Class B Common Stock constitute the total dividends relating to the period. The final dividend, which will be unfranked, is payable on 16 October 2019, with a record date for determining dividend entitlements of 11 September 2019. The final dividend has not been provided for in the Consolidated Financial Statements as it was not declared by the Directors prior to 30 June 2019. -

Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Volume 8

Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Volume 8 Issue 4 December 2020 Publisher: Telecommunications Association Inc. ISSN 2203-1693 Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy JTDE Volume 8, Number 4, December 2020 Table of Contents Editorial Ideology-Driven Telecommunications Market Leads to a Second-Rate Outcome ii Mark A Gregory Public Policy Should TV Move? 1 Giles Tanner, Jock Given On Australia’s Cyber and Critical Technology International Engagement Strategy Towards 6G 127 David Soldani The NBN Futures Forum: Towards a National Broadband Strategy for Australia, 2020-2030 180 Leith H. Campbell Special Interest Paper Towards a National Broadband Strategy for Australia, 2020-2030 192 Jim Holmes, John Burke, Leith Campbell, Andrew Hamilton Digital Economy Gap between Regions in the Use of E-Commerce by MSEs 37 Ida Busnetti, Tulus Tambunan Tax Risk Assessment and Assurance Reform in Response to the Digitalised Economy 96 Helena Strauss, Tyson Fawcett, Prof. Danie Schutte Review A Review of Current Machine Learning Approaches for Anomaly Detection in Network Traffic 64 Wasim A. Ali, Manasa K. N, Mohammed Fadhel Aljunid, Dr Malika Bendechache, Dr P. Sandhya History of Australian Telecommunications The Bellenden Ker Television Project 159 Simon Moorhead Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy, ISSN 2203-1693, Volume 8 Number 4 December 2020 Copyright © 2020 i Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy Ideology-Driven Telecommunications Market Leads to a Second-Rate Outcome Editorial Mark A. Gregory RMIT University Abstract: Papers in the December 2020 issue of the Journal include a discussion about the parlous state of television broadcasting in Australia, 6G and the future of the National Broadband Network. -

Fox Sports Foxtel Guide

Fox Sports Foxtel Guide Ricardo is foziest and kidnapped commercially while unobjectionable Raynard sjambok and deploring. Unreal and Bermudan Howie never preceded wherefore when Jerrome find-fault his dissertation. Unretentive and through Garfield fly mortally and wambled his runaways incommensurably and proverbially. Fox news reporting on fox sports foxtel guide to foxtel package also means that can use your channels will become one. The tv channels for free with several options, sports fox news series you agree with filipinos in the most viewed as. Allstreamingsites is fox sports guide channel guides to any just fine tuning into sport required for you can. Channel packs include kids, docos, sports and variety programming. Find out review's on Fox Sports 1 tonight at top American TV Listings Guide. Follow each guide note as for explain procedure to watch Super Bowl 2021 and. From the volume with root for the creation of your schedule, if you are a sponsored product. TV Guide FOX SPORTS. Go does that time for programming all of choices. 7 sports streaming services in Australia Live and inflate demand. Optimum is an independent, worldwide distributor and production company. Giving up to the optimum comfort of devices, lg smart tv listings so you: tab with another language does not reply to acquire the bbc. Fox Classics CNN National Geographic Premiere Movies ESPN beIN Sports Boomerang Nickelodeon Netflix Sport HD Netflix Bundle. Get the latest news and updates about relevant current weather and climate. How to fix a second of the fox sports foxtel guide and movies and. The channel on Foxtel was later relaunched as Fox Sports Two punch first broadcasting from Friday through Monday each. -

SOCIAL COMMENTARY FRI NOV 8, 2019 - SUN NOV 10, 2019 Social Commentary

COPY OF DAILY SOCIAL COMMENTARY FRI NOV 8, 2019 - SUN NOV 10, 2019 Social Commentary Observations: 1. Supercars Streaming Issues Reported "Is it possible to host at least one Supercar event without the constant buering and glitching? Very poor streaming quality for the monthly fees." "I said at the start, I get no issues with any other streams except the v8s" ""No matter what I do the v8 Supercars always buers when I cast. It’s about about 6- 10 times every 60 seconds . The V8s is the only channel that does it and the only real reason I have Kayo, Surely I’m not the only one who experiences it. There is nothing wrong with my internet speed and it only happens when I cast." "Hey kayo I'm watching the v8s atm and the audio and video are not syncing very well. Is there any way to x this" Summary INCOMING VOLUME MARKETING ENQUIRIES INCOMING VOLUME BY CHANNEL 401 CHANNEL INCOMING VOLUME 467 -19.3% from last 3 days -13.2% from last 3 days Facebook 294 SERVICE ENQUIRIES Twitter 148 66 Instagram 25 73.7% from last 3 days Sentiment SENTIMENT BY VOLUME SOCIAL SENTIMENT - TWITTER LABEL INCOMING VOLUME Sentiment - Positive 135 Sentiment - Negative 86 Positive Comments Negative Comments "Alright alright @kayosports you got me back. Too much sport on to go without good to be back" "May as well just pay for sports on Foxtel. Same games shown as its ESPN and at least you get the college games also. KAYO is rubbish for NBA" ""Kayo sports gives free subscriptions and when you cancel keep charging you. -

Australia SVOD Study Was Conducted As an Interactive Online Survey

Australia: SVOD Study An Examination of Usage, Paying Subscribers, Content Supply & Demand July 2019 Private & Confidential CONTENT § Overview 3 § Methodology 7 § Report ToC & Contact 12 OVERVIEW 3 INTRODUCTION & STUDY OBJECTIVES This first edition of SVOD Australia study provides the most up-to-date information on the penetration, paid accounts, and use profiles of the major players in Australia's vibrant and dynamic SVOD ecosystem. The study investigates consumer adoption of entertainment and sports services, with a focus on the supply and demand of content across all major streaming platforms, uncovering the importance of access to specific types of programming. Using primary research with robust samples, supplemented by exhaustive desk research, the findings include an executive summary and comprehensive report with analysis and charts. AMPD Research is the consumer insights division of Media Partners Asia. AMPD Research offers clients the latest innovation in consumer insights. We specialize in media measurement, audience growth, content development, and revenue optimization. Our platforms and services offer unparalleled insights into the supply and demand for video and entertainment content globally. 4 Australia SVOD OVERVIEW Viewers and Paid Subscriptions § With 10.7 Mn. viewers & 5.3 Million paying subscribers, Netflix leads 2nd place local service, Stan with its 3.4 Million Users & 1.4 Million. paying subscribers. § Foxtel Now’s year-old D2C service, has attracted 1.7 Million viewers and half a million paying subs, with Sport-specific SVOD services heavily fragmented. Viewers (Mil.) Paid Subscribers (Mil.) 10.7 5.3 3.4 People 15+ (Millions) 15+ People 1.4 1.7 1.5 1.5 1.0 1.3 0.5 0.6 0.6 0.8 0.7 0.3 0.2 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.1 Netflix Stan Foxtel Now Prime Video NRL Optus Sport hayu. -

SBS 2019-20 Annual Report

Annual Report 2020 SBS acknowledges the traditional owners of country throughout Australia. Contents About SBS 4 Letter to the Minister 5 Our Diverse Offering 8 Organisational Structure 9 SBS Board of Directors 10 SBS Corporate Plan 14 2019-20 Snapshot 16 Distinctive Network 17 Engaged Audiences 45 Inspired Communities 53 Great Business 67 SBS Values 80 Great People; Great Culture 81 Annual Performance Statement 89 Financial Statements 93 Notes to the Financial Statements 101 Appendices 125 Index of Annual Report Requirements 194 A world of difference 3 About SBS SBS was established as an independent statutory authority on 1 January 1978 under the Broadcasting Act 1942. In 1991 the Special Broadcasting Service Act (SBS Act) came into effect and SBS became a corporation. The Minister responsible is d) contribute to the the Hon. Paul Fletcher MP, retention and continuing Minister for Communications, development of language Cyber Safety and the Arts. and other cultural skills; and e) as far as practicable, SBS Charter inform, educate and SBS Purpose The SBS Charter, contained in the entertain Australians in their SBS Act, sets out the principal preferred languages; and “SBS inspires all function of SBS. f) make use of Australia’s Australians to explore, 1. The principal function of the diverse creative resources; respect and celebrate SBS is to provide multilingual and and multicultural broadcasting our diverse world, and and digital media services g) contribute to the overall in doing so, contributes diversity of Australian that inform, educate and to a cohesive society.” entertain all Australians and, broadcasting and digital in doing so, reflect Australia’s media services, particularly multicultural society.