Red Flags in Scleroderma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding and Managing Scleroderma

Understanding and Managing Scleroderma A publication of Scleroderma Foundation 300 Rosewood Drive, Suite 105 Danvers, MA 01923 Maureen D. Mayes, M.D., M.P.H. Understanding and Understanding My notes and Managing Scleroderma Managing Scleroderma This booklet is intended to help people with scleroderma, their families and others interested ________________________ in learning more about the disease to better understand what scleroderma is, what effects ________________________ it may have, and what those with scleroderma can do to help themselves and their physicians ________________________ manage the disease. It answers some of the most frequently asked questions about ________________________ A publication of Maureen D. Mayes, M.D., M.P.H. Scleroderma Foundation 300 Rosewood Drive, Suite 105 scleroderma. Danvers, MA 01923 800-722-HOPE (4673) www.scleroderma.org www.facebook.com/sclerodermaUS www.twitter.com/scleroderma ________________________ Disclaimer The Scleroderma Foundation does not provide medical advice nor does it ________________________ endorse any drug or treatment mentioned herein. ________________________ The material contained in this booklet is presented for general information only. It is not intended to provide medical advice, to answer questions specific to the condition or problems of particular individuals, nor in ________________________ any way to substitute for the professional advice and care of qualified physicians. Mention of particular drugs and/or treatments is for ________________________ information purposes only and does not constitute an endorsement of said drugs and/or treatments. ________________________ Thanks! ________________________ The Scleroderma Foundation expresses its deep appreciation to the many ________________________ physicians whose efforts have led to this booklet. Special thanks are owed to Maureen D. Mayes, M.D., M.P.H., of the ________________________ University of Texas McGovern Medical School, Houston. -

Dermatological Findings in Common Rheumatologic Diseases in Children

Available online at www.medicinescience.org Medicine Science ORIGINAL RESEARCH International Medical Journal Medicine Science 2019; ( ): Dermatological findings in common rheumatologic diseases in children 1Melike Kibar Ozturk ORCID:0000-0002-5757-8247 1Ilkin Zindanci ORCID:0000-0003-4354-9899 2Betul Sozeri ORCID:0000-0003-0358-6409 1Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Department of Dermatology, Istanbul, Turkey. 2Umraniye Training and Research Hospital, Department of Child Rheumatology, Istanbul, Turkey Received 01 November 2018; Accepted 19 November 2018 Available online 21.01.2019 with doi:10.5455/medscience.2018.07.8966 Copyright © 2019 by authors and Medicine Science Publishing Inc. Abstract The aim of this study is to outline the common dermatological findings in pediatric rheumatologic diseases. A total of 45 patients, nineteen with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), eight with Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), six with scleroderma (SSc), seven with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and five with dermatomyositis (DM) were included. Control group for JIA consisted of randomly chosen 19 healthy subjects of the same age and gender. The age, sex, duration of disease, site and type of lesions on skin, nails and scalp and systemic drug use were recorded. χ2 test was used. The most common skin findings in patients with psoriatic JIA were flexural psoriatic lesions, the most common nail findings were periungual desquamation and distal onycholysis, while the most common scalp findings were erythema and scaling. The most common skin finding in patients with oligoarthritis was photosensitivity, while the most common nail finding was periungual erythema, and the most common scalp findings were erythema and scaling. We saw urticarial rash, dermatographism, nail pitting and telogen effluvium in one patient with systemic arthritis; and photosensitivity, livedo reticularis and periungual erythema in another patient with RF-negative polyarthritis. -

Visual Recognition of Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases

Seeing the Signs: Visual Recognition of Autoimmune Connective Tissue Diseases Utah Association of Family Practitioners CME Meeting at Snowbird, UT 1:00-1:30 pm, Saturday, February 13, 2016 Snowbird/Alta Rick Sontheimer, M.D. Professor of Dermatology Univ. of Utah School of Medicine Potential Conflicts of Interest 2016 • Consultant • Paid speaker – Centocor (Remicade- – Winthrop (Sanofi) infliximab) • Plaquenil – Genentech (Raptiva- (hydroxychloroquine) efalizumab) – Amgen (etanercept-Enbrel) – Alexion (eculizumab) – Connetics/Stiefel – MediQuest • Royalties Therapeutics – Lippincott, – P&G (ChelaDerm) Williams – Celgene* & Wilkins* – Sanofi/Biogen* – Clearview Health* Partners • 3Gen – Research partner *Active within past 5 years Learning Objectives • Compare and contrast the presenting and Hallmark cutaneous manifestations of lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis • Compare and contrast the presenting and Hallmark cutaneous manifestations of morphea and systemic sclerosis Distinguishing the Cutaneous Manifestations of LE and DM Skin involvement is 2nd most prevalent clinical manifestation of SLE and 2nd most common presenting clinical manifestation Comprehensive List of Skin Lesions Associated with LE LE-SPECIFIC LE-NONSPECIFIC Cutaneous vascular disease Acute Cutaneous LE Vasculitis Leukocytoclastic Localized ACLE Palpable purpura Urticarial vasculitis Generalized ACLE Periarteritis nodosa-like Ten-like ACLE Vasculopathy Dego's disease-like Subacute Cutaneous LE Atrophy blanche-like Periungual telangiectasia Annular Livedo reticularis -

A Review of the Evidence for and Against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A Review of the Evidence for and against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis Traci A. Wilgus 1,*, Sara Ud-Din 2 and Ardeshir Bayat 2,3 1 Department of Pathology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 2 Centre for Dermatology Research, NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Research, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PT, UK; [email protected] (S.U.-D.); [email protected] (A.B.) 3 MRC-SA Wound Healing Unit, Division of Dermatology, University of Cape Town, Observatory, Cape Town 7945, South Africa * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-614-366-8526 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 12 December 2020; Published: 18 December 2020 Abstract: Scars are generated in mature skin as a result of the normal repair process, but the replacement of normal tissue with scar tissue can lead to biomechanical and functional deficiencies in the skin as well as psychological and social issues for patients that negatively affect quality of life. Abnormal scars, such as hypertrophic scars and keloids, and cutaneous fibrosis that develops in diseases such as systemic sclerosis and graft-versus-host disease can be even more challenging for patients. There is a large body of literature suggesting that inflammation promotes the deposition of scar tissue by fibroblasts. Mast cells represent one inflammatory cell type in particular that has been implicated in skin scarring and fibrosis. Most published studies in this area support a pro-fibrotic role for mast cells in the skin, as many mast cell-derived mediators stimulate fibroblast activity and studies generally indicate higher numbers of mast cells and/or mast cell activation in scars and fibrotic skin. -

Genes in Eyecare Geneseyedoc 3 W.M

Genes in Eyecare geneseyedoc 3 W.M. Lyle and T.D. Williams 15 Mar 04 This information has been gathered from several sources; however, the principal source is V. A. McKusick’s Mendelian Inheritance in Man on CD-ROM. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Other sources include McKusick’s, Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders. Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press 1998 (12th edition). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim See also S.P.Daiger, L.S. Sullivan, and B.J.F. Rossiter Ret Net http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet disease.htm/. Also E.I. Traboulsi’s, Genetic Diseases of the Eye, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998. And Genetics in Primary Eyecare and Clinical Medicine by M.R. Seashore and R.S.Wappner, Appleton and Lange 1996. M. Ridley’s book Genome published in 2000 by Perennial provides additional information. Ridley estimates that we have 60,000 to 80,000 genes. See also R.M. Henig’s book The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, published by Houghton Mifflin in 2001 which tells about the Father of Genetics. The 3rd edition of F. H. Roy’s book Ocular Syndromes and Systemic Diseases published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002 facilitates differential diagnosis. Additional information is provided in D. Pavan-Langston’s Manual of Ocular Diagnosis and Therapy (5th edition) published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002. M.A. Foote wrote Basic Human Genetics for Medical Writers in the AMWA Journal 2002;17:7-17. A compilation such as this might suggest that one gene = one disease. -

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: Diagnosis and Management From

REVIEW ARTICLE Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Ferrata Storti diagnosis and management from Foundation the hematologist’s perspective Athena Kritharis,1 Hanny Al-Samkari2 and David J Kuter2 1Division of Blood Disorders, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ and 2Hematology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA ABSTRACT Haematologica 2018 Volume 103(9):1433-1443 ereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler- Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal dominant disorder that Hcauses abnormal blood vessel formation. The diagnosis of hered- itary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is clinical, based on the Curaçao criteria. Genetic mutations that have been identified include ENG, ACVRL1/ALK1, and MADH4/SMAD4, among others. Patients with HHT may have telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations in various organs and suffer from many complications including bleeding, anemia, iron deficiency, and high-output heart failure. Families with the same mutation exhibit considerable phenotypic variation. Optimal treatment is best delivered via a multidisciplinary approach with appropriate diag- nosis, screening and local and/or systemic management of lesions. Antiangiogenic agents such as bevacizumab have emerged as a promis- ing systemic therapy in reducing bleeding complications but are not cur- ative. Other pharmacological agents include iron supplementation, antifibrinolytics and hormonal treatment. This review discusses the biol- ogy of HHT, management issues that face -

Foot Pain in Scleroderma

Foot Pain in Scleroderma Dr Begonya Alcacer-Pitarch LMBRU Postdoctoral Research Fellow 20th Anniversary Scleroderma Family Day 16th May 2015 Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Presentation Content n Introduction n Different types of foot pain n Factors contributing to foot pain n Impact of foot pain on Quality of Life (QoL) Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Scleroderma n Clinical features of scleroderma – Microvascular (small vessel) and macrovascular (large vessel) damage – Fibrosis of the skin and internal organs – Dysfunction of the immune system n Unknown aetiology n Female to male ratio 4.6 : 1 n The prevalence of SSc in the UK is 8.21 per 100 000 Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Foot Involvement in SSc n Clinically 90% of SSc patients have foot involvement n It typically has a later involvement than hands n Foot involvement is less frequent than hand involvement, but is potentially disabling Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Different Types of Foot Pain Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ischaemic Pain (vascular) Microvascular disease (small vessel) n Intermittent pain – Raynaud’s (spasm) • Cold • Throb • Numb • Tingle • Pain n Constant pain – Vessel center narrows • Distal pain (toes) • Gradually increasing pain • Intolerable pain when necrosis is present Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ischaemic Pain (vascular) Macrovascular disease (large vessels) n Intermittent and constant pain – Peripheral Arterial Disease • Intermittent claudication – Muscle pain (ache, cramp) during walking • Aching or burning pain • Night and rest pain • Cramps Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Ulcer Pain n Ulcer development – Constant pain n Infected ulcer – Unexpected/ excess pain or tenderness Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine Neuropathic Pain n Nerve damage is not always obvious. -

A Acanthosis Nigricans, 139 Acquired Ichthyosis, 53, 126, 127, 159 Acute

Index A Anti-EJ, 213, 214, 216 Acanthosis nigricans, 139 Anti-Ferc, 217 Acquired ichthyosis, 53, 126, 127, 159 Antigliadin antibodies, 336 Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), 79, 81 Antihistamines, 324 Adenocarcinoma, 115, 116, 151, 173 Anti-histidyl-tRNA-synthetase antibody Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), 229 (Anti-Jo-1), 6, 14, 140, 166, 183, Adhesion molecules, 225–226 213–216 Adrenal gland carcinoma, 115 Anti-histone antibodies (AHA), 174, 217 Age, 30–32, 157–159 Anti-Jo-1 antibody syndrome, 34, 129 Alanine aminotransferase (ALT, ALAT), 16, Anti-Ki-67 antibody, 247 128, 205, 207, 255 Anti-KJ antibodies, 216–217 Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, 216 Anti-KS, 82 Aldolase, 14, 16, 128, 129, 205, 207, 255, 257 Anti-Ku antibodies, 163, 165, 217 Aledronate, 325 Anti-Mas, 217 Algorithm, 256, 259 Anti-Mi-2 Allergic contact dermatitis, 261 antibody syndrome, 11, 129, 215 Alopecia, 62, 199, 290 antibodies, 6, 15, 129, 142, 212 Aluminum hydroxide, 325, 326 Anti-Myo 22/25 antibodies, 217 Alzheimer’s disease-related proteins, 190 Anti-Myosin scintigraphy, 230 Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, 151, 166, 182, Antineoplastic agents, 172 212, 215 Antineoplastic medicines, 169 Aminoquinolone antimalarials, 309–310, 323 Antinuclear antibody (ANA), 1, 141, 152, 171, Amyloid, 188–190 172, 174, 213, 217 Amyopathic DM, 6, 9, 29–30, 32–33, 36, 104, Anti-OJ, 213–214, 216 116, 117, 147–153 Anti-p155, 214–215 Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, 263 Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), 127, Antisynthetase syndrome, 11, 33–34, 81 130, 219 Anaphylaxi, 316 Anti-PL-7 antibody, 82, 214 Anasarca, -

Prevalence and Incidence of Rare Diseases: Bibliographic Data

Number 1 | January 2019 Prevalence and incidence of rare diseases: Bibliographic data Prevalence, incidence or number of published cases listed by diseases (in alphabetical order) www.orpha.net www.orphadata.org If a range of national data is available, the average is Methodology calculated to estimate the worldwide or European prevalence or incidence. When a range of data sources is available, the most Orphanet carries out a systematic survey of literature in recent data source that meets a certain number of quality order to estimate the prevalence and incidence of rare criteria is favoured (registries, meta-analyses, diseases. This study aims to collect new data regarding population-based studies, large cohorts studies). point prevalence, birth prevalence and incidence, and to update already published data according to new For congenital diseases, the prevalence is estimated, so scientific studies or other available data. that: Prevalence = birth prevalence x (patient life This data is presented in the following reports published expectancy/general population life expectancy). biannually: When only incidence data is documented, the prevalence is estimated when possible, so that : • Prevalence, incidence or number of published cases listed by diseases (in alphabetical order); Prevalence = incidence x disease mean duration. • Diseases listed by decreasing prevalence, incidence When neither prevalence nor incidence data is available, or number of published cases; which is the case for very rare diseases, the number of cases or families documented in the medical literature is Data collection provided. A number of different sources are used : Limitations of the study • Registries (RARECARE, EUROCAT, etc) ; The prevalence and incidence data presented in this report are only estimations and cannot be considered to • National/international health institutes and agencies be absolutely correct. -

Eosinophilic Fasciitis (Shulman Syndrome)

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION Eosinophilic Fasciitis (Shulman Syndrome) Sueli Carneiro, MD, PhD; Arles Brotas, MD; Fabrício Lamy, MD; Flávia Lisboa, MD; Eduardo Lago, MD; David Azulay, MD; Tulia Cuzzi, MD, PhD; Marcia Ramos-e-Silva, MD, PhD GOAL To understand eosinophilic fasciitis to better manage patients with the condition OBJECTIVES Upon completion of this activity, dermatologists and general practitioners should be able to: 1. Recognize the clinical presentation of eosinophilic fasciitis. 2. Discuss the histologic findings in patients with eosinophilic fasciitis. 3. Differentiate eosinophilic fasciitis from similarly presenting conditions. CME Test on page 215. This article has been peer reviewed and is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing approved by Michael Fisher, MD, Professor of medical education for physicians. Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Albert Einstein College of Medicine designates Review date: March 2005. this educational activity for a maximum of 1 This activity has been planned and implemented category 1 credit toward the AMA Physician’s in accordance with the Essential Areas and Policies Recognition Award. Each physician should of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical claim only that credit that he/she actually spent Education through the joint sponsorship of Albert in the activity. Einstein College of Medicine and Quadrant This activity has been planned and produced in HealthCom, Inc. Albert Einstein College of Medicine accordance with ACCME Essentials. Drs. Carneiro, Brotas, Lamy, Lisboa, Lago, Azulay, Cuzzi, and Ramos-e-Silva report no conflict of interest. The authors report no discussion of off-label use. Dr. Fisher reports no conflict of interest. We present a case of eosinophilic fasciitis, or Shulman syndrome apart from all other sclero- Shulman syndrome, in a 35-year-old man and dermiform states. -

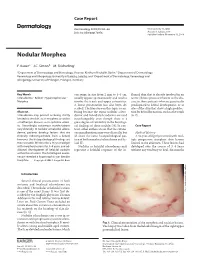

Nodular Morphea

Case Report Dermatology 2009;218:63–66 Received: July 13, 2008 DOI: 10.1159/000173976 Accepted: July 23, 2008 Published online: November 13, 2008 Nodular Morphea a b c F. Kauer J.C. Simon M. Sticherling a b Department of Dermatology and Venerology, Vivantes Klinikum Neukölln, Berlin , Department of Dermatology, c Venerology and Allergology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig , and Department of Dermatology, Venerology and Allergology, University of Erlangen, Erlangen , Germany Key Words can range in size from 2 mm to 4–5 cm, flamed skin that is already involved in an -Scleroderma ؒ Keloid ؒ Hypertrophic scar ؒ usually appear spontaneously and tend to active fibrotic process inherent to the dis Morphea involve the trunk and upper extremities. ease in those patients who are genetically A linear presentation has also been de- predisposed to keloid development, or at scribed. The literature on this topic is con- sites of the skin that show a high predilec- Abstract fusing because the terms ‘nodular sclero- tion for keloid formation, such as the trunk Scleroderma may present as being strictly derma’ and ‘keloidal scleroderma’ are used [6, 7] . limited to the skin, as in morphea, or within interchangeably even though there is a a multiorgan disease, as in systemic sclero- great degree of variability in the histologi- sis. Accordingly, cutaneous manifestations cal findings of these nodules [4] . In con- C a s e R e p o r t vary clinically. In nodular or keloidal sclero- trast, other authors stress that the cutane- derma, patients develop lesions that are ous manifestations may vary clinically, but Medical History clinically indistinguishable from a keloid; all share the same histopathological pat- A 16-year-old girl presented with mul- however, the histopathological findings are tern of both morphea/scleroderma and ke- tiple progressive morpheic skin lesions more variable. -

Topical Photodynamic Therapy for Localized Scleroderma

Acta Derm Venereol 2000; 80: 26±27 Topical Photodynamic Therapy for Localized Scleroderma SIGRID KARRER, CHRISTOPH ABELS, MICHAEL LANDTHALER and ROLF-MARKUS SZEIMIES Department of Dermatology, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany Therapy of localized scleroderma is unsatisfactory, with MATERIAL AND METHODS numerous treatments being used that have only limited success Patients or considerable side-effects. The aim of this trial was to determine whether topical photodynamic therapy would be Five patients aged between 21 and 63 years with biopsy-proven effective in patients with localized scleroderma. Five patients localized scleroderma (morphoea) were studied. All patients had evidence of progressive disease, i.e. lesions showed an in¯ammatory with progressive disease, in whom conventional therapies had reaction and increase in size. In each patient the condition had failed, were treated by application of a gel containing 3% previously failed to respond to potent topical corticosteroids, systemic 5-aminolevulinic acid followed by irradiation with an incoherent therapy with penicillin and/or PUVA bath photochemotherapy. lamp (40 mW/cm2, 10 J/cm2). The treatment was performed Patients were required to discontinue all therapy at least 4 weeks once or twice weekly for 3 ± 6 months. In all patients the before study initiation. The most affected sclerotic plaque of each therapy was highly effective for sclerotic plaques, as measured patient was judged at baseline and then every 2 weeks during by a quantitative durometer score and a clinical skin score. The treatment. Sclerotic plaques were assessed by a clinical skin score (10) only side-effect was a transient hyperpigmentation of the and the durometer score (11).