Convergence and Divergence in Stadium Ownership Structures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Football Program 2020

FOOTBALL PROGRAM 2020 20 19 92nd SEASON OF Wesgroup is a proud supporter of Vancouver College’s Fighting Irish Football Team. FOOTBALL 5400 Cartier Street, Vancouver BC V6M 3A5 TABLE OF CONTENTS Principal’s Message ...............................................................2 Irish Football Team Awards 1941-2019 ..............................19 Head Coach’s Message .........................................................2 Irish Records 1986-2019 ......................................................22 Vancouver College Staff and Schedules 2020 .......................3 Irish Provincial Championship Game 2020 Fighting Irish Coaches and Supporting Staff ................4 Award Winners 1966-2018 .................................................29 Irish Alumni Currently Playing in the CFL and NFL ................5 Back in the Day ....................................................................29 2020 Fighting Irish Graduating Seniors .................................6 Irish Cumulative Record Against Opponents 1929-2018 .....30 Fighting Irish Varsity Statistical Leaders 2019 ......................8 Fighting Irish Varsity Football Team 2019 ...........................34 Vancouver College Football Awards 2019 .............................9 Irish Statistics 1996-2018 ...................................................35 Irish Varsity Football Academic Awards ...............................10 Archbishops’ Trophy Series 1957-2018 .............................38 Irish Academics 2020 ..........................................................10 -

Alice Springs Sports Facilties Master Plan

ALICE SPRINGS SPORTS FACILTIES MASTER PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND STRATEGY - FINAL | JANUARY 2020 HEAD OFFICE 304/91 Murphy Street Richmond VIC 3121 p (03) 9698 7300 e [email protected] w www.otiumplanning.com.au ABN: 30 605 962 169 ACN: 605 962 169 CAIRNS OFFICE 44/5 Faculty Close Smithfield QLD 4878 Contact: Martin Lambert p (07) 4055 6250 e [email protected] OTIUM PLANNING GROUP OFFICES « Brisbane « Cairns « Melbourne « New Zealand « Perth « Sydney OPG, IVG and PTA Partnership has offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, Shanghai and Beijing. © 2020 Otium Planning Group Pty. Ltd. This document may only be used for the purposes for which it was commissioned and in accordance with the terms of engagement for the commission. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 4 1.1. Alice Springs 4 1.2. Population 4 1.3. Purpose of the Plan 5 1.4. Facilities Included 5 2. SPORT IN ALICE SPRINGS 6 2.1. Summary of Sport Participation 6 2.2. Sporting Facilities 8 2.3. Unique Alice Springs 9 3. COMMUNITY AND STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT 10 3.1. Engagement Process 10 3.2. Community Feedback 11 3.3. Sport Club and Organisation Feedback 12 3.4. Government and Council 13 4. SUMMARY OF KEY STRATEGIC AND FACILITY ISSUES 14 4.1. Lack of Sports Fields/ Access to Fields 14 4.2. Legacy of Past Decisions and Need for Master Planning Precincts 15 4.3. Developing a Standard of Provision and Facilities Hierarchy 15 4.4. Priorities Emerging from a Standard of Provision Approach 16 5. RECOMMENDATIONS 17 5.1. -

Cardiff City Football Club

AWAY FAN GUIDE 2015/16 Welcome to Cardiff City Football Club The Cardiff City away fan guide has been designed to help you get the most out of your visit here at Cardiff City Stadium. This guide contains all the information you need to know about having a great away day here with us, including directions, match day activities, where to park and much more. At Cardiff City Stadium we accommodate all supporters, of all ages, with a large number of activities for everyone. Our aim is to ensure each fan has an enjoyable match-day experience regardless of the result. Cardiff City Football Club would like to thank you for purchasing your tickets; we look forward to welcoming you to Cardiff City Stadium, and wish you a safe journey to and from the venue. We are always looking at ways in which we can improve your experience here with us - so much so, that we were the first club to set up an official Twitter account and e-mail address specifically for away fans to give feedback. So, if you have any comments or questions please do not hesitate to contact us at: @CardiffCityAway or [email protected] AWAY FAN GUIDE 2015/16 How to get to the Stadium by Car If you’re traveling to the Stadium by car, access to us from the M4 is easy. Leave the M4 at junction 33 and take the A4232 towards Cardiff/Barry. Exit the A4232 on to the B4267 turn- off, signposted towards Cardiff City Stadium. Follow the slip-road off the B4267 and take the second available exit off the roundabout on to Cars Hadfield Road, and then take the third left in to Bessemer Road. -

The Adelaide Oval SMA Ltd (AOSMA) Is Pleased to Provide Its Written Submission to the Select Committee on the Redevelopment of Adelaide Oval

^val 31 January 2019 Leslie Guy Secretary to the Committee C/- Parliament House GPO Box 572 Adelaide 5001 By email: [email protected] Dear Ms Guy, The Adelaide Oval SMA Ltd (AOSMA) is pleased to provide its written submission to the Select Committee on the Redevelopment of Adelaide Oval. In doing so, we provide the following context we believe will be of significant value to the members of the Committee. In reviewing the first five years of operations of the redeveloped Adelaide Oval, it is important to understand the events that led to the formation of AOSMA and the creation of the eventual management model that was approved by Cabinet in 2011. AOSMA is a joint venture company of the two entities responsible for growing and developing the codes of cricket and football in South Australia - the South Australian Cricket Association (SACA) and the South Australian National Football League (SANFL). Both are not-for-profit organisations that, historically, derived the bulk of their revenues from staging events at their respective grounds-Adelaide Oval and Football Park (AAMI Stadium). This income was critical to their respective abilities to fund, manage and support everything from junior participation to elite level talent development, clubs and competitions. In 2009, the then Labor Government offered one chance at transformational change. However, it put the onus of proving the incredibly complex business case of bringing football and cricket together at a redeveloped Adelaide Oval on SACA and SANFL. Then-and only then-would the necessary funding for the project be provided. While this created an opportunity for cricket and football to help shape their futures, it was also a task that necessitated both organisations to make sacrifices in meeting the Government's demands. -

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures

Big Bash League 2018-19 Fixtures DATE TIME MATCH FIXTURE VENUE 19 December 18:15 Match 1 Brisbane Heat v Adelaide Strikers The Gabba 20 December 19:15 Match 2 Melbourne Renegades v Perth Scorchers Marvel Stadium 21 December 19:15 Match 3 Sydney Thunder v Melbourne Stars TBD 22 December 15:30 Match 4 Sydney Sixers v Perth Scorchers SCG 18:00 Match 5 Brisbane Heat v Hobart Hurricanes Carrara Stadium 23 December 18:45 Match 6 Adelaide Strikers v Melbourne Renegades Adelaide Oval 24 December 15:45 Match 7 Hobart Hurricanes v Melbourne Stars Bellerive Oval 19:15 Match 8 Sydney Thunder v Sydney Sixers Spotless Stadium 26 December 16:15 Match 9 Perth Scorchers v Adelaide Strikers Optus Stadium 27 December 19:15 Match 10 Sydney Sixers v Melbourne Stars SCG 28 December 19:15 Match 11 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Thunder Bellerive Oval 29 December 19:00 Match 12 Melbourne Renegades v Sydney Sixers Docklands 30 December 19:15 Match 13 Hobart Hurricanes v Perth Scorchers York Park 31 December 18:15 Match 14 Adelaide Strikers v Sydney Thunder Adelaide Oval 1 January 13:45 Match 15 Brisbane Heat v Sydney Sixers Carrara Stadium 19:15 Match 16 Melbourne Stars v Melbourne Renegades MCG 2 January 19:15 Match 17 Sydney Thunder v Perth Scorchers Spotless Stadium 3 January 19:15 Match 18 Melbourne Renegades v Adelaide Strikers TBC 4 January 19:15 Match 19 Hobart Hurricanes v Sydney Sixers Bellerive Oval 5 January 17:15 Match 20 Melbourne Stars v Sydney Thunder Carrara Stadium 18:30 Match 21 Perth Scorchers v Brisbane Heat Optus Stadium 6 January 18:45 Match -

Cardiff-City-Stadium-Away-Fans-2018

Visiting Fan Guide 2018-2020 Croeso i Gymru. Welcome to Wales. Welcome to Cardiff, the capital city of Wales. This guide has been compiled in conjunction with the FAW and FSF Cymru, who organise Fan Embassies. The purpose is to help you get the most out of your visit to Wales. The guide is aimed to be fan friendly and contain all the information you’ll need to have an enjoyable day at the Cardiff City stadium, including directions, where to park and so much more. At the Cardiff stadium we accommodate supporters of all gender, age or nationality. Our aim is to ensure that each fan has an enjoyable matchday experience-irrespective of the result. The FAW thank you for purchasing tickets and look forward to If you have any queries, please contact us. greeting you in Cardiff, where members of the FSF Cymru fan Twitter @FSFwalesfanemb embassy team will be available to assist you around the stadium. Email [email protected] How to get to the Stadium by car If you are travelling to the stadium by We have an away parking area located in that obstructs footways and/or private car, access from the motorway is easy. the away compound of CCS (accessible entrances. Cardiff Council enforcement Leave the M4 at junction 33 and take up until 30 minutes prior to kick-off), officers and South Wales Police officers the A4232 towards Cardiff/Barry. Exit which can be accessed via Sloper Road work event days and will check that all the A4232 on to the B4267 turnoff, (next to the HSS Hire Shop). -

Tickets.T20worldcup.Com ICC T20 World Cup 2020 Ticket Terms and Conditions

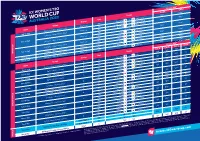

Prices (A$)* Date Venue Group Time Teams Adult Child Sat 15 Feb Brisbane - Allan Border Field Warm-up PM Australia v West Indies $10^ Free^ AM Sri Lanka v South Africa Adelaide - Karen Rolton Oval Warm-up $10^ Free^ PM England v New Zealand Sun 16 Feb AM Q1 v Q2 Brisbane - Allan Border Field Warm-up $10^ Free^ PM India v Pakistan AM Australia v South Africa Adelaide - Karen Rolton Oval Warm-up $10^ Free^ WARM-UP Tue 18 Feb PM England v Sri Lanka Brisbane - Allan Border Field Warm-up PM India v West Indies $10^ Free^ Wed 19 Feb Adelaide - Karen Rolton Oval Warm-up AM New Zealand v Q2 $10^ Free^ Thu 20 Feb Brisbane - Allan Border Field Warm-up AM Q1 v Pakistan $10^ Free^ Prices (A$)* Date Venue Group Time Teams Cat A Cat B Cat C Child Fri 21 Feb Sydney Showground Stadium A N Australia v India $40 $30 $20 $5 B PM West Indies v Q2 Sat 22 Feb Perth - WACA Ground $30 $20 $20^ $5 A N New Zealand v Sri Lanka Sun 23 Feb Perth - WACA Ground B N England v South Africa $30 $20 $20^ $5 PM Australia v Sri Lanka Mon 24 Feb Perth - WACA Ground A $30 $20 $20^ $5 N India v Q1 PM England v Q2 Wed 26 Feb Canberra - Manuka Oval B $30 $20 $20^ $5 N West Indies v Pakistan Melbourne - Junction Oval A PM India v New Zealand $30 $20^ – $5 Thu 27 Feb Canberra - Manuka Oval A N Australia v Q1 $30 $20 $20^ $5 PM South Africa v Q2 Fri 28 Feb Canberra - Manuka Oval B $30 $20 $20^ $5 N England v Pakistan GROUP STAGE AM New Zealand v Q1 Sat 29 Feb Melbourne - Junction Oval A $30 $20^ – $5 PM India v Sri Lanka PM South Africa v Pakistan Sun 1 Mar Sydney Showground Stadium B $30 $20 – $5 N England v West Indies AM Sri Lanka v Q1 Mon 2 Mar Melbourne - Junction Oval A $30 $20^ – $5 PM Australia v New Zealand PM Pakistan v Q2 Tue 3 Mar Sydney Showground Stadium B $30 $20 – $5 N West Indies v South Africa Semi-Final 1 PM TBC v TBC Thu 5 Mar Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) $50 $35 $20 $5 Semi-Final 2 N TBC v TBC FINALS Sun 8 Mar Melbourne Cricket Ground (MCG) Final N TBC v TBC $60 $40 $20 $5 AM – Morning match. -

2018 TOYOTA AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON ROUND 1 ROUND 7 ROUND 13 ROUND 19 Thursday, March 22 Friday, May 4 Thursday, June 14 Friday, July 27 Richmond Vs

2018 TOYOTA AFL PREMIERSHIP SEASON ROUND 1 ROUND 7 ROUND 13 ROUND 19 Thursday, March 22 Friday, May 4 Thursday, June 14 Friday, July 27 Richmond vs. Carlton (MCG) (N) Geelong Cats vs. GWS GIANTS (GS) (N) Port Adelaide vs. Western Bulldogs (AO) (N) Essendon vs. Sydney Swans (ES) (N) Friday, March 23 Saturday, May 5 Friday, June 15 Saturday, July 28 Essendon vs. Adelaide Crows (ES) (N) Western Bulldogs vs. Gold Coast SUNS (MARS) Sydney Swans vs. West Coast Eagles (SCG) (N) Richmond vs. Collingwood (MCG) Saturday, March 24 Essendon vs. Hawthorn (MCG) Saturday, June 16 Geelong Cats vs. Brisbane Lions (GS) St Kilda vs. Brisbane Lions (ES) West Coast Eagles vs. Port Adelaide (PS) (T) Carlton vs. Fremantle (ES) GWS GIANTS vs. St Kilda (SP) (T) Port Adelaide vs. Fremantle (AO) (T) Sydney Swans vs. North Melbourne (SCG) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. St Kilda (MS) (T) Gold Coast SUNS vs. Carlton (MS) (N) Gold Coast SUNS vs. North Melbourne (CS) (N) Adelaide Crows vs. Carlton (AO) (N) Hawthorn vs. Adelaide Crows (MCG) (N) Adelaide Crows vs. Melbourne (AO) (N) Hawthorn vs. Collingwood (MCG) (N) Sunday, May 6 Sunday, June 17 Sunday, July 29 Sunday, March 25 Geelong Cats vs. Richmond (MCG) Richmond vs. Fremantle (MCG) North Melbourne vs. West Coast Eagles (BA) GWS GIANTS vs. Western Bulldogs (UNSW) St Kilda vs. Melbourne (ES) Byes: Brisbane Lions, Collingwood, Essendon, Melbourne vs. Geelong Cats (MCG) Western Bulldogs vs. Port Adelaide (MARS) Brisbane Lions vs. Collingwood (G) (T) GWS GIANTS, Melbourne, North Melbourne. West Coast Eagles vs. Sydney Swans (PS) (N) Fremantle vs. -

The Canadian Gunner L'artilleur Canadien 2008

na • _ ~u0~ ¶OLO~ DUC~~ THE CANADIAN GUNNER L’ARTILLEUR CANADIEN 2008 THE CANADIAN GUNNER L’ARTILLEUR CANADIEN Volume 43 April 2009 Avril 2009 Captain-General, The Royal Regiment Capitaine-général. le Régiment royal of Canadian Artillery de l’Artillerie canadienne Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Sa Majesté la Reine Elizabeth II Colonel Commandant, The Royal Regiment Colonel commandant, le Régiment royal Of Canadian Artillery de l’Artillerie canadienne Brigadier General E.B. Beno, OMM, CD Brigadier Général E.B. Beno, OMM, CD Senior Serving Gunner Artilleur en service principal Lieutenant General J. Arp, CMM, CD Lieutenant Général J. Arp, CMM, CD Director of Artillery Directeur de l’Artillerie Colonel D.D. Marshall, OMM, CD Colonel D.D. Marshall, OMM, CD Commander Home Station Commandant de la garnison Régimentaire Lieutenant-Colonel J.J. Schneiderbanger, CD Lieutenant-colonel J.J. Schneiderbanger, CD Editor-in-Chief Rédacteur en chef Vacant Vacant Managing Editor Directeur de la rédaction Captain G.M. Popovits, CD Capitaine G.M. Popovits, CD Production Production The Shilo Stag The Shilo Stag Printers Imprimeurs Leech Printing Ltd. Leech Printing Ltd. L’Artilleur canadien est une publication annuelle fiancée par le The Canadian Gunner is published annually and is financed Fonds régimentaire de l’ARC et a bonn ement. by the RCA Regimental Fund and subscriptions. Les auteurs expriment leur propre opinion et il ne s’agit pas The views expressed by the authors are their own and do not nécessairement de la politque offcielle. necessarily reflect official policy. Tous les textes et les photos soumis deviennent propriétés All copy and photos submitted become the property of The de l’Artilleur canadien, à moins qu’ils ne soient accompagnés Canadian Gunner unless accompanied by a statement that d’un avis indiquant qu’ils ne sont que prêtés et qu’ils doivent they are on loan and are required to be returned. -

BC Pavilion Corporation

REVISED SERVICE PLAN 2013/2014 to 2015/2016 CONTENTS Message from Board Chair to Minister Responsible ................................................................................ 3 Organizational Overview ............................................................................................................................. 5 Government’s Letter of Expectations ........................................................................................................ 6 Corporate Governance .............................................................................................................................. 11 Strategic Context ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Internal Operating Environment ............................................................................................................... 13 Economic, Industry and Social Factors Affecting Performance ............................................................... 13 Risks and Opportunities .......................................................................................................................... 15 Operational Capacity ............................................................................................................................... 15 Goals, Key Strategies, Performance Measures and Targets ................................................................. 16 Strategic Goals ..................................................................................................................................... -

Media Release from the Australian Football League

MEDIA RELEASE FROM THE AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL LEAGUE The AFL today wrote to all clubs to advise the AFL Commission had approved a change to the 22-match fixture structure whereby each club would now have two byes through the season comprising 22 matches across 25 weeks, starting from next year’s 2014 Toyota AFL Premiership Season. As part of the introduction of a second bye to better manage the workload on players and clubs throughout the year, the premiership season will now commence with a split round across the weekends of March 14-16 and March 21-23 (five matches and four matches respectively on those two weekends). The pre-season period will be revitalised to feature two matches per Club scheduled nationally, with a continued focus on regional areas that don’t normally host premiership matches, as well as matches in metropolitan areas and managing the travel load across all teams. In place of the NAB Cup Grand Final, the AFL is currently considering options for a representative-style game in the final week of the pre-season, together with intra-club matches for all teams, before round one gets underway. AFL General Manager - Broadcasting, Scheduling and Major Projects Simon Lethlean said the first group of club byes were likely to be across rounds 8-10 (three weeks of six matches per round) with the second group of club byes to be placed in the run to the finals in the region of rounds 18-19 (one week of five matches and one week of four matches). All up, clubs would each play 22 games across 25 weeks through March 14-16 (week one of round one) to August 29-31. -

ST. VINCENT DE PAUL CATHOLIC SCHOOL 116 Fermanagh Ave

ST. VINCENT DE PAUL CATHOLIC SCHOOL 116 Fermanagh Ave. Toronto Ontario M6R 1M2 Telephone: 416-393-5227 Fax: 416-393-5873 BULLETIN APRIL 22nd to 26h 2019 FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @SVdP_PRINCIPAL Monday - Easter Monday wishing everyone a Happy Easter Laura DiManno 416-393-5227 - Earth Day PRINCIPAL Tuesday John Wujek 416-222-8282 ext. 5371 - City Divisional Chess Tournament @ St. Helen’s (Ms. McInerney) - 6:30PM Presentation to parents by PC. J. Abramowitz on Social Media SUPERINTENDENT Awareness & Safety – all are welcome Teresa Lubinski 416-512-3404 Wednesday TRUSTEE - Casa Loma Trip (Ms. Pavesi, Ms. Moore, Ms. Pinto) St. Vincent de Paul Roman Catholic Church - Boys Basketball Tournament @Our Lady of Sorrow 416-535-7646 - Grad Photo Retake 263 Roncesv alles Av e. Toronto Ont. M 6R 2L9 Thursday PARISH - Grad Photo Retakes Jo-Ann Dav is and Alessand ra D’ Ambrosio - Girls Basketball Tournament @Pope Francis 416-222 -8282 ext. 88227 - Ms. Kairys’ Retirement Party CSPC CHAIR Friday www.tcdsb.org/cpic - Dance-a-Thon CPIC (PA R EN T EN GA GEM EN T - TC D SB ) - Pizza Lunch www.tcdsb. or g/ oapce-t oront o - Chess & Math OAPC E TORONTO ( PR O VI N CI A L V OI C E F OR P A R EN T S) - Creative Club Gr.2 416-393-5227 9 AM – 3:30 PM 11:45 AM – 12:45 PM DATES TO REMEMBER EN R OLLM EN T HOU RS OF OPERA TION LU NC H H OU R th April 29 – Eco Team - Toronto School Clean Up @ Sorauren Park (Ms.