Yuxia Wang.Pdf (1.068Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preikestolen Cruise & Hike

Preikestolen cruise & hike 22 May - 31 September 2021 This is a challenging hike without guide. Remember to bring food, good hiking boots and clothes for various weather conditions! Departures boat and bus: Boat from Strandkaien, Stavanger 22 - 31 May, Departure Saturdays and Sundays at 11:00 1 June - 20 June, 23 August - 30 September Departure Saturdays and Sundays at 10:00 21 June - 22 August Daily at 10:00 May June-Sept. Arr. Forsand (leave the boat) apx. 13:10 apx. 12:10 Dep. Forsand (by bus) apx. 13:15 apx. 12:15 Arr. Preikestolen Mountain Lodge apx. 13:40 apx. 12:40 Bus departure from Preikestolen Mountain Lodge to downtown Stavanger - 45 Minutes: 21 June - 22 August Daily at 18:15 Free wifi on board the boat! 23 August - 30 September Saturdays and Sundays at 18:15 Photos: OutdoorlifeNorway In cooperation with: Fjord magic, followed by an unforgettable hike. E-mail: [email protected] - rodne.no Alsvik Mosterøy The hike to Preikestolen takes roughly two hoursTysdalsvatn each way from Preikestolen Mountain Lodge. Sandv 13 Tau Solbakk 13 Jørpeland Ryfast Tunnel Preikestolen Hundvåg Mountain Lodge Hengjanefossen E39 Departure Preikestolen Strandkaien,Vågen Kallali Idse Idsal You made it! 509 You’ve Fossmark earned 13 bragging rights! ;-) Hommersåk 516 Ådnøy Oanes 13 Your hike Forsand Espedal starts and E39 Lauvvik ends here. Enjoy your adventure! Sandnes HelleSustainable fjord experiences Rødne aims to run the most environ- mentally friendly operations possible. By contributing to greenerFrafjord fjord tourism and 2.0 km 2.5 km Neverdals Tjødnane minimizing noise and emissions from our skaret Dirdal 604 m boats we give our guests a sustainable 1.5 km 2.7km Krogebekk- Stidele myrane fjord experience of the highest quality. -

Nasjonal Turistveg Ryfylke

NATUR TURISTVEGER Nasjonal Turistveg Ryfylke Hardanger/Odda/Bergen Odda Nasjonal turistveg Hardanger Hardangervidda Oslo/ Røldal Telemark Kyrkjenuten E 134 29 1602 Rv.13 nd Røldal ala rd nd o ala H g Øvre Sandvatn o Røldalsvatnet Attractions in Ryfylke R E 134 n e ar d k 1. Kjerag r es o Reinaskar- j fj k Breifonn a Indrejord Røldalsvegen Ek 2. Preikestolen kr nuten Å Buer 1241 3. Flørli Power station Slettedalsvatnet Skånevik Breiborg and steps - 4444 SAUDA Fv. 520 Rv.13 Melsnuten 4. Landa, prehistoric village Nordstøldalen (closed in winter) 1573 5. Månafossen fallsUtbjoa Hellandsbygd 6. Jørpelandsholmen islet & Nesflaten Etne Sauda Scenic Route Ryfylke Roaldkvam The Norwegian Stonehenge 27 23 Saudasjøen Storelva Fitjarnuten 28 Skaulen 1504 7. Rock carvings at Solbakk 1538 E 134 Svandals- Gjuvastøl Kvernheia fossen 26 n 8. Flor & Fjære e 1182 d r Roaldsnuten o j j j j 1155 f f f 9. Villa Tou/Mølleparken Svandalenl f Dyrskarnuten 22 a a a 25 a d d d Hor d Maldal 1296 u u u 10. Årdal old church da u Ølen land a Bråtveit Rog S 11. The Fairytale Forest aland Suldalsvegen 12. Vigatunet farm 24 Suldalsvatnet Jonstøl 13. Hauske old arched stone bridge Scenic Route Ryfylke Sandeid VINDAFJORD Fv. 520 Vanvik 21 Snønuten 14. The Spinnery 1604 Scenic Route Ryfylke Kolbeinstveit 15. Ritland Crater Hylsfjorden Vinjarnuten Rv. 46 1105 S MAP: ELLEN JEPSON MAP: a 16. Jelsa church and village n SULDAL d Såta e id Suldalsosen 1423 17. Ostasteidn (view point) f jo Vikedal Ropeid r n 18. Blåsjø d 20 Sand låge e 19 ldals n Su DYRAHEIO 19. -

On the Agromyzidae (Diptera) in Norway, Part 2

© Norwegian Journal of Entomology. 25 June 2013 On the Agromyzidae (Diptera) in Norway, Part 2 ARILD ANDERSEN Andersen, A. 2013. On the Agromyzidae (Diptera) in Norway, Part 2. Norwegian Journal of Entomology 60, 39–56. The present paper comments on thirty-one of the ninety-nine species belonging to the Agromyzidae genera Chromatomyia Hardy 1849, Napomyza Westwood, 1840 and Phytomyza Fallén, 1810, and presently known to occur in Norway. Seven species are reported new to the Norwegian fauna; Napomyza hirticornis (Hendel, 1932), N. nigriceps van der Wulp, 1871, Phytomyza melana Hendel, 1920, P. nigrifemur Hering, 1934, P. ranunculicola Hering, 1949, P. rhabdophora Griffiths, 1964, and P. subrostrata Frey, 1946. In addition new regional data is given for twenty-four species previously reported from Norway. The biology of the larva, when known, and the distribution in Norway and Europe are commented on for each of the species. Key words: Agromyzidae, biology, Chromatomyia, Napomyza, Phytomyza, Diptera, distribution, Norway. Arild Andersen, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences, Høgskoleveien 7, NO-1432 Ås, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Introduction during several projects and collecting trips in many parts of Norway, but mainly in meadows The larvae of Agromyzidae mine in leaves, with a rich flora in South-Eastern Norway. If stems, seeds and roots of plants. Accordingly, a species has been found more than once in the many Agromyzidae species are important pests same district or EIS square, only data from in cultural plants. Recently some data has been the first record is given. In such cases the total published on the Norwegian fauna of Agromyzidae number of specimens investigated of the species (Andersen & Jonassen 1994, Andersen et al. -

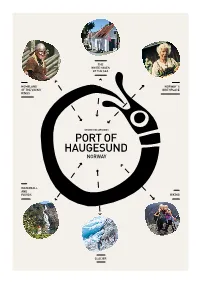

Port of Haugesund Norway

THE WHITE HAVEN BY THE SEA HOMELAND NORWAY´S OF THE VIKING BIRTHPLACE KINGS SHORE EXCURSIONS PORT OF HAUGESUND NORWAY WATERFALL AND FJORDS HIKING GLACIER CRUISE DESTINATION HAUGESUND, NORWAY CRUISE DESTINATION HAUGESUND, NORWAY NORDVEGEN HISTORY CENTRE tells the story about how Avaldsnes became The First Royal Throne of Norway. HOMELAND OF THE VIKING KINGS, FROM The Viking Farm. NORWAY´S BIRTHPLACE In Norway, and at the heart of Fjord Norway, you will find the Haugesund region. This is the Homeland of the Viking Kings – Norway’s birthplace. Here you can discover the island of Karmøy, where Avaldsnes is situated – Norway’s oldest throne. PRIOR TO the Viking Age, Avaldsnes was a seat of Avaldsnes is therefore a key point in understanding power. This is where the Vikings ruled the route the fundamental importance of voyage by sea in that gave its name to Norway – the way north. terms of Norway’s earliest history. The foundation Around 870 AD, King Harald the Fairhaired made stone of modern Norway was laid in 1814, but the Avaldsnes his main royal estate, which was country’s historical foundation is located at Avaldsnes. to become Norway’s oldest throne. Today, one can visit St. Olav’s church at Avaldsnes, From the time the first seafaring vessels were built as well as Nordvegen History Center, and the in the late Stone Age and up to the Middle Ages, Viking Farm. These are all places of importance the seat of power of the reigning princes and kings for the Vikings and the history of Norway. has been located at Avaldsnes. -

The Stavanger Region

WELCOME ON BOARD Rødne Fjord Cruise and the crew welcome you on board! The trip will take us far into the country and show us idyllic island scenery as well as a wild and beautiful West Norwegian nature. In order to be prepared in case of an emergency, we ask you to please read the safety information on board. A STAVANGER Stavanger is today the fourth largest city in Norway with approximately 120.000 inhabitants. Stavanger is considered to be the oil capital of Norway, but before oil was discovered in the North Sea it was fish, specifically sardines that kept the city going. B TINGHOLMEN/HØGSFJORD After passing the historically interesting Tingholmen, where King Olav Tryggvason held his national assembly in 998, we proceed into the Høgsfjord. Many Stavanger families have their summerhouses along the coastline here. C LYSEFJORD The Lysefjord is 42 km long. The name dates back to the old Norse name Lýsir or light. It is believed this refers to the lightly colored granite that can be found in the fjord. The Lysefjord was formed by glaciers during the ice ages. During the most recent ice age, about 10.000 years ago, Norway was covered with a layer ofice that was up to 2.000 meters thick. The fjord is a deep ravine between mountainous valley sides. Between Oanes and Forsand, there is an end moraine of sand, and the fjord is only 10-20 meters deep at this point. Ever since man first settled in the area, fishing and hunting have been important activities here. -

Getting Here from Stavanger: from Sandnes: from Tau / Jørpeland

Flørli 4.444 – getting here www.florli.no · 0047 902 65 133 · [email protected] Flørli can only be reached by ferry, there are two ferries, four daily calls. You can bring your car on the ferry or leave it on the quay in for example Lauvvik or Lysebotn. Groups can charter a boat, see under www.florli.no/events. Time schedules: Kolumbus (MS Lysefjord, a fast ferry, takes 10 cars): https://kolumbus.no/globalassets/ruter/baatruter/stavanger-lysebotn-kombibat.pdf To order for car: https:// bestilling.kolumbus.no. Passengers buy tickets on board. The Fjords AS (MS Sognefjord, a large ferry with sightseeing, takes 40 cars): https://www.visitflam.com/en/sightseeing/experiences-in-the-fjords/fjord-cruise-lysefjorden/ From Stavanger: Monday, Wednesday and Friday 13:00 direct Kolumbus ferry leaving from the Fiskepirterminal in the city centre. All other days: drive or take the bus to Sandnes and Lauvvik. The ferry goes back to Stavanger every Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7:35, arriving at the Fiskepirterminal at 9:00. Regular airport shuttles from there (www.flybussen.no/stavanger). From Sandnes: There are many busses and trains between Stavanger and Sandnes. From Sandnes, take bus 47 to Lauvvik or drive yourself along RV13. Bus 47 drives Monday – Saturday, about every 2 hours. Schedule: https://www.kolumbus.no/globalassets/ruter/bussruter/stavanger-sandnes-omegn/47-sandnes-sviland- lauvvik.pdf. You can also order a taxi to get you to Lauvvik ferry quay. From Tau / Jørpeland: Take the busline 100 Tau to Jørpeland. This bus corresponds with the ferry from Stavanger (Fiskepirterminal), https://www.kolumbus.no/globalassets/ruter/bussruter/ryfylke/100-tau-jorpeland.pdf. -

Southern Coast of Norway

SOUTHERN COAST OF NORWAY Day 1: ARRIVAL OSLO Arrival to the airport of Oslo Gardermoen. Pick-up your rental car and drive to the centre of the city. We recommend a visit to the famous Vigeland Sculpture Park, the Viking Ship Museum where the best preserved Viking ships ever found are on display, the Fram Museum where the entire original Arctic exploration ship Fram is exhibited with its original interior and inventory, the Kon-tiki Museum which contains original vessels and objects from Thor Heyerdal’s many expeditions or one of the many other interesting sights in Oslo. Accommodation at 3 star+ class hotel in Oslo, centrally located Day 2: OSLO – KRISTIANSAND (325 KM) Breakfast at the hotel. In the morning, departure from Oslo and start your tour in the southern part of Norway, “The Norwegian Riviera”. This stretch of coast has more sunny days per year than anywhere else in the country, making it a holiday paradise for Norwegians. Drive via Larvik, an attractive port town, which has a fine maritime museum, and continue to Kristiansand. Southern Norway’s largest city is charming with weathered old homes and a pulsating summer atmosphere. The city was built by King Christian IV in 1641 in his characteristic chessboard layout featuring four town “quarters”. The centre of the town is an attractive mixture of historic attractions and relaxed seaside atmosphere. Kristiansand’s most popular attraction is Kristiansand Dyrepark, which contains five parks of different themes, including a zoo, a water park and Kardemomme By (Cardamom City, inspired by the children’s books of Norwegian author and illustrator Thorbjørn Egner). -

From Stavanger: Monday, Wednesday and Friday 13:00 Direct Kolumbus Ferry Leaving from the Fiskepirterminal in the City Centre

Flørli 4.444 – getting here www.florli.no · 0047 902 65 133 · [email protected] Flørli can only be reached by ferry, there are two ferries, four daily calls. You can bring your car on the ferry or leave it on the quay in for example Lauvvik, Forsand or Lysebotn. Groups can charter a boat, see under www.florli.no/events. Ferry schedule summary: Kolumbus (MS Lysefjord, a fast ferry, takes 10 cars): https://kolumbus.no/globalassets/ruter/baatruter/stavanger-lysebotn-kombibat.pdf To order for car: https://bestilling.kolumbus.no or call +47 916 52 800. Passengers buy tickets on board. TheFjords AS (MS Sognefjord, a large ferry with sightseeing, takes 40 cars): https://www.visitflam.com/en/sightseeing/experiences-in-the-fjords/fjord-cruise-lysefjorden/. To order for car: +47 415 36 398. Passengers buy tickets on board. With Kolumbus (not on Saturday) With TheFjords (all days) To Flørli from Lauvvik / Forsand 06:05 / 13:55 / (16:45 fr/su) 09:00 / 15:00 From Flørli to Lauvvik / Forsand 07:35 / 15:45 / (18:00 fr/su) 12:45 / 18:45 To Flørli from Lysebotn 07:20 / 15:30 / (17:45 fr/su) 12:00 / 18:00 From Flørli to Lysebotn 07:00 / 14:50 / (17:25 fr/su) 10:45 / 16:45 From Stavanger: Monday, Wednesday and Friday 13:00 direct Kolumbus ferry leaving from the Fiskepirterminal in the city centre. All other days: drive or take the bus to Sandnes and Lauvvik. The ferry goes back to Stavanger every Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 7:35, arriving at the Fiskepirterminal at 9:00. -

Nasjonal Turistveg RYFYLKE

Nasjonal turistveg RYFYLKE Snøen ligger ofte lenge utover sommeren på fjellovergangen mellom Sauda og Røldal. © Roger Ellingsen / Statens vegvesen -lan gs frodige fjo rder og nakne fjell Bobilen Bobilen 50 Nr . 2 • Mars 2016 Nr . 2 • Mars 2016 51 NASJONAL TURISTVEG RYFYLKE Attraksjonen Nasjonale turist- veger er 18 kjøreturer gjennom vakker norsk natur der opplevelsen forsterkes med nyskapende arkitektur og tankevekkende kunst på tilrette- lagte utsiktspunkter og rasteplasser. Statens vegvesen står bak dette utviklingsarbeidet. Bobilen presenterer i samarbeid med Turistvegseksjonen en serie med turistveg- strekningene. Ryfylke er den 18. og siste i rekken. Utsikt innover Som den siste i serien, går turen Om turistvegen den 40 km lange Lysefjorden. denne gang til Nasjonal turistveg Nasjonal turistveg Ryfylke går mellom Oanes ved Lysefjorden og Hordalia ved Røldal og er 183 km lang (rv 13/fv 46/520). © Trine Kanter Zerwekh / Ryfylke. Fjordlandskapet byr på store Det er to korte fergestrekninger, mellom Lauvvik og Oanes Statens vegvesen kontraster - fra variert, vakkert og og mellom Hjelmeland og Nesvik. Fjellovergangen mellom Hellandsbygd og Røldal er vinterstengt, vanligvis mellom frodig fjordlandskap, små skjærgårds - november og juni. (Fra påske mellom Breiborg og Røldal.) idyller og velpleide strandsteder til Det er ikke uvanlig med 5-6 m snø på fjellet. Vinterstid kan du Helleristningene komme deg fra Sand til Røldal via rv 13, langs Suldalslågen, på Solbakk rå steinurer, blankskurte svaberg, Suldalsvatnet og Brattlandsdalen. Dette er uansett et glim- er fra ca år stupbratte fjellsider og nakent høyfjell rende alternativ også om sommeren, om du ønsker å lage en 500 f.Kr. flott rundreise. med snø utover sommeren. -

Pulpit Rock from Egersund

PULPIT ROCK FROM EGERSUND PACKED LUNCH FROM THE HOTEL We offer our guests the opportunity to prepare a packed lunch to bring on trips, at a cost of 65,- per meal. Pulpit Rock (Preikestolen) is one of Rogaland’s most visited attractions and one of Norway’s most spectacular photo subjects. In 2011, Pulpit Rock was named one of the most spectacular viewing points in the world by both CNN Go and Lonely Planet. A hike to the mountain plateau, which towers 604 meters above the SUGGESTED fjord, is a fantastic nature experience. Many will agree that seeing PACKING LIST the Pulpit Rock is the highlight of any visit to Ryfylke and the - Comfortable Stavanger region. waterproof shoes Pulpit Rock towers 604 meters above Lysefjord. It was probably - Warm and windproof formed at a time where the glacier was located right alongside and clothing, woollen hat, above the pulpit, approximately 10 000 years ago. Water froze in mittens and neck crevices in the mountain and broke loose giant blocks of rock, which warmer the glacier transported away. Pulpit Rock as a tourist destination was - Mat to sit on discovered around 1900. - Map - Plenty to eat and drink - Good mood Grand Hotell Egersund AS, Johan Feyersgate 3, PB 16, 4379 Egersund, Telephone + 47 51 49 60 60 www.grand-egersund.no / [email protected] Access: From Egersund: Follow Rv 44 along Tengesdal to E-39, and then towards Ålgård. Take a right onto Rv 45 Oltedalsvegen, and follow it until you get to Rv 508 Seldalsvegen. Continue to Rv 13 Lauviksvegen. -

Rødne Fjord Cruise

WELCOME ON BOARD Rødne Fjord Cruise and the crew welcome you on board! The trip will take us far into the country and show us idyl-lic island scenery as well as a wild and beautiful West Norwegian nature. In order to be prepared in case of an emergency, we ask you to please read the safety information on board. A STAVANGER Stavanger is today the fourth largest city in Norway with approximately 120.000 inhabitants. Stavanger is considered to be the oil capital of Norway, but before oil was discovered in the North Sea it was fish, specifically sardines that kept the city going. B TINGHOLMEN/HØGSFJORD After passing the historically interesting Tingholmen, where King Olav Tryggvason held his national assembly in 998, we proceed into the Høgsfjord. Many Stavanger families have their summerhouses along the coastline here. C LYSEFJORD The Lysefjord is 42 km long. The name dates back to the old Norse name Lýsir or light. It is believed this refers to the lightly colored granite that can be found in the fjord. The Lysefjord was formed by glaciers during the ice ages. During the most recent ice age, about 10.000 years ago, Norway was covered with a layer ofice that was up to 2.000 meters thick. The fjord is a deep ravine between mountainous valley sides. Between Oanes and Forsand, there is an end moraine of sand, and the fjord is only 10-20 meters deep at this point. Ever since man first settled in the area, fishing and hunting have been important activities here. -

Fjordtours & Things to Do

2018 fjordtours & things to do Stavanger Foto Terje Rakke- Life-RegionStavange: Nordic Terje Foto Lysefjord Foto: Fjord Norway Fjord Foto: in a nutshell Calm & beautiful dramatic & rough Stavanger, round trip adult NOK 1 290 Child (4-15) NOK 1 050 Prices include transport cruise boat, buses and train Duration Departure / arrival Experience the heights and highlights of Lysefjord 1 day, weekdays 07:30 Bus from Stavanger / and Western Norway — all in one day! Embark on Season 16:00 Train arrival in Stavanger this trip and see the magnificent scenery of Western 4. June - 31. August Norway; encompassing fjords, mountains, waterfalls and idyllic islands! Tour highlights • Relax and enjoy a journey by bus through a beautiful landscape • Take in the breathtaking views of the Lysefjord from Lysebotn the Eagle’s Nest, 3.250 feet above sea level Stavanger Ørneredet • Treat yourself to scenic thrills on the fjord cruise Lauvik on the Lysefjord, with the towering Pulpit Rock as a Sandnes natural highlight • Take a scenic bus ride to Sandnes, followed by a short journey on the Southern Railway back to Stavanger See timetable and itinerary on the next page TourTimetables higlights & itineraries Find activities and book at fjordtours.com Lysefjord in a nutshell Round trip from Stavanger Stavanger-Lysebotn-Lauvvik-Sandnes-Stavanger 2018 WEEKDAYS 4.6-31.8 Bus from Stavanger 07:30 to Lysebotn 11:45 Fjord cruise from Lysebotn 12:00 To Lauvvik 14:30 Bus from Lauvvik 14:45 To Sandnes 15:23 Train from Sandnes 15:44 To Stavanger 16:00 Pulpit Rock & Norway in a nutshell® Foto Terje Rakke- Life-RegionStavange: Nordic Terje Foto The world’s most spectacular viewing point by both CNN Go & Lonely Planet adult from NOK 3 250* Prices include transport by fjord cruise boat (classic-* or premium boat), buses and trains.