United States National Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 147

Q 11 U563 CRLSSI BULLETIN 147 MAP U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM 's SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM Bulletin 147 ARCHEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL INVESTIGATIONS IN SAMANA DOMINICAN REPUBLIC BY HERBERT W. KRIEGER Curator of Ethnology, United States National Museum UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1929 For sale by ths Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 40 Cents ADVERTISEMENT The scientific publications of the National Museum include two series, known, respectively, as Proceedings and Bulletin. The Proceedings, begun in 1878, is intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original papers, based on the collections of the National Museum, that set forth newly acquired facts in biology, anthropology, and geology, with descriptions of new forms and revisions of limited groups. Copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, are distributed as published to libraries and scientific organ- izations and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The dates at which these separate papers are published are recorded in the table of contents of each of the volumes. The Bulletin, the first of which was issued in 1875, consist of a series of separate publications comprising monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occasion- ally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, cata- logues of type-specimens, special collections, and other material of similar nature. The majority of the volumes are octavo in size, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which large plates were regarded as indispensable. In the Bulletin series appear volumes under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herharium, in octavo form, published by the National Museum since 1902, which contain papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum. -

Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria

Electoral Observations in the Americas Series, No. 13 Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 Secretary General César Gaviria Assistant Secretary General Christopher R. Thomas Executive Coordinator, Unit for the Promotion of Democracy Elizabeth M. Spehar This publication is part of a series of UPD publications of the General Secretariat of the Organization of American States. The ideas, thoughts, and opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the OAS or its member states. The opinions expressed are the responsibility of the authors. OEA/Ser.D/XX SG/UPD/II.13 August 28, 1998 Original: Spanish Electoral Observation in the Dominican Republic 1998 General Secretariat Organization of American States Washington, D.C. 20006 1998 Design and composition of this publication was done by the Information and Dialogue Section of the UPD, headed by Caroline Murfitt-Eller. Betty Robinson helped with the editorial review of this report and Jamel Espinoza and Esther Rodriguez with its production. Copyright @ 1998 by OAS. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced provided credit is given to the source. Table of contents Preface...................................................................................................................................vii CHAPTER I Introduction ............................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II Pre-election situation .......................................................................................................... -

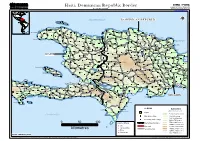

Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected]

GIMU / PGDS Haiti, Dominican Republic Border Geographic Information and Mapping Unit As of February 2004 Population and Geographic Data Section Email : [email protected] ATLANTIC OCEAN DOMINICANDOMINICAN REPUBLICREPUBLIC !!! Voute I Eglise ))) ))) Fond Goriose ))) ))) ))) Saint Louis du Nord ))) ))) ))) ))) Cambronal Almaçenes ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Monte Cristi ))) Jean Rabel ))) ))) Bajo Hondo ))) ))) ))) Gélin ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabana Cruz ))) La Cueva ))) Beau Champ ))) ))) Haiti_DominicanRepBorder_A3LC Mole-Saint-Nicolas ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Bassin ))) Barque ))) Los Icacos ))) ))) Bajo de Gran Diablo )))Puerto Plata ))) Bellevue ))) Beaumond CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN HAITIENHAITIEN ))) Palo Verde CAPCAPCAP HAITIEN )HAITIEN)HAITIEN) ))) PUERTOPUERTOPUERTO PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL ))) ))) Bambou ))) ))) Imbert ))) VVPUERTOPUERTOPUERTO))) PLATA PLATAPLATA INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONALINTERNATIONAL VV ))) VV ))) ))) ))) VV ))) Sosúa ))) ))) ))) Atrelle Limbé VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) ))) VV ))) ))) ))) Fatgunt ))) Chapereau VV Lucas Evangelista de Peña ))) Agua Larga ))) El Gallo Abajo ))) ))) ))) ))) Grande Plaine Pepillo Salcedo))) ))) Baitoa ))) ))) ))) Ballon ))) ))) ))) Cros Morne))) ))) ))) ))) ))) Sabaneta de Yásica ))) Abreu ))) ))) Ancelin ))) Béliard ))) ))) Arroyo de Leche Baie-de-Henne ))) ))) Cañucal ))) ))) ))) ))) ))) La Plateforme ))) Sources))) Chaudes ))) ))) Terrier Rouge))) Cacique Enriquillo ))) Batey Cerro Gordo ))) Aguacate del Limón ))) Jamao al Norte ))) ))) ))) Magante Terre Neuve -

Justice Project Final Report

JUSTICE PROJECT FINAL REPORT FINAL REPORT: JULY 2008–JULY 2012 JULY 2012 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by DAI. JUSTICE PROJECT FINAL REPORT FINAL REPORT: JULY 2008–JULY 2012 Program Title: USAID Justice Project Sponsoring USAID Office: USAID/Dominican Republic Contract Number: DFD-I-07-05-00220-00/07 Contractor: DAI Date of Publication: July 2012 Author: Josefina Coutino, Rosalia Sosa, Elizabeth Ventura, Martha Contreras The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS CONTENTS ......................................................................................................................... V BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. VII ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................ VIII INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 NATIONAL CONTEXT .......................................................................................................... 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... 3 PROJECT ADMINISTRATION .......................................................................................... -

Dominican Republic

THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC By Ivette E. Torres The economy of the Dominican Republic grew by 4.8% in Production of gold in 1995 from Rosario Dominicana real terms in 1995 according to the Central Bank. But S.A.’s Pueblo Viejo mine increased almost fivefold from that inflation was 9.2%, an improvement from that of 1994 when of 1994 to 3,288 kilograms after 2 years of extremely low inflation exceeded 14%. The economic growth was production following the mine's closure at the end of 1992. stimulated mainly by the communications, tourism, minerals, The mine reopened in late 1994. commerce, transport, and construction sectors. According to During the last several decades, the Dominican Republic the Central Bank, in terms of value, the minerals sector has been an important world producer of nickel in the form increased by more than 9%.1 of ferronickel. Ferronickel has been very important to the During the year, a new law to attract foreign investment Dominican economy and a stable source of earnings and was being considered by the Government. The law, which Government revenues. In 1995, Falcondo produced 30, 897 would replace the 1978 Foreign Investment Law (Law No. metric tons of nickel in ferronickel. Of that, 30,659 tons 861) as modified in 1983 by Law No. 138, was passed by was exported, all to Canada where the company's ferronickel the Chamber of Deputies early in the year and was sent to the was purchased and marketed by Falconbridge Ltd., the Senate in September. The law was designed to remove company's majority shareholder. -

Taino Survival in the 21St Century Dominican Republic

Portland State University PDXScholar Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations Black Studies 2002 Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is From Spain: Taino Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic Pedro Ferbel-Azcarate Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/black_studies_fac Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Ferbel, P. J. (2002). "Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is from Spain: Taíno Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic". KACIKE: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Black Studies Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. KACIKE: Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology ISSN 1562-5028 Special Issue edited by Lynne Guitar NEW DIRECTIONS IN TAINO RESEARCH http://www.kacike.org/Current.html Not Everyone Who Speaks Spanish is from Spain: Taino Survival in the 21st Century Dominican Republic Dr. P. J. Ferbel Introduction that has persisted to this day. That heritage, together with the historical The national identity of the evidence for Taíno survival presented by Dominican Republic is based on an my colleagues Lynne Guitar and Jorge idealized story of three cultural roots-- Estevez, points me to the understanding Spanish, African, and Taíno--with a that the Taíno people were never extinct selective amnesia of the tragedies and but, rather, survived on the margins of struggles inherent to the processes of colonial society to the present. -

Situation Report 2 –Tropical Storm Olga – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 14 DECEMBER 2007

Tropical Storm Olga Dominican Republic Situation Report No.2 Page 1 Situation Report 2 –Tropical Storm Olga – DOMINICAN REPUBLIC 14 DECEMBER 2007 This situation report is based on information received from the United Nations Resident Coordinators in country and OCHA Regional Office in Panama. HIGHLIGHTS • Tropical Storm Olga has claimed the lives of 35 people. Some 49,170 persons were evacuated and 3,727 are in shelters. • Needs assessments are ongoing in the affected areas to update the Noel Flash Appeal. SITUATION 5. The Emergency Operations Centre (COE) is maintaining a red alert in 30 provinces: Santo 1. Olga developed from a low-pressure system into a Domingo, Distrito Nacional, San Cristóbal, Monte named storm Monday 10 December, although the Plata, Santiago Rodríguez, Dajabón, San Pedro de Atlantic hurricane season officially ended November Macorís, Santiago, Puerto Plata, Espaillat, Hermanas 30. The centre of Tropical Storm Olga passed Mirabal (Salcedo), Duarte (Bajo Yuna), María through the middle of the Dominican Republic Trinidad Sánchez, Samaná, Montecristi, Valverde- overnight Tuesday to Wednesday on a direct Mao, Sánchez Ramírez, El Seibo, La Romana, Hato westward path. Olga has weaken to a tropical Mayor (in particular Sabana de la Mar), La depression and moved over the waters between Cuba Altagracia, La Vega, Monseñor Nouel, Peravia, and Jamaica. The depression is expected to become a Azua, San José de Ocoa, Pedernales, Independencia, remnant low within the next 12 hours. San Juan de la Maguana and Barahona. Two provinces are under a yellow alert. 2. Olga is expected to produce additional rainfall, accumulations of 1 to 2 inches over the southeastern Impact Bahamas, eastern Cuba, Jamaica and Hispaniola. -

AMB Despedida

Dear Ambassador Robin S. Bernstein, Over your two and half years you have strengthened the bilateral relationship and made a profound impact on the Dominican people and relations between our countries. Just as the Dominican Republic will always be in your heart, the Dominican people will always have you in their hearts. As President Luis Abinader said during the ceremony to present you with the Orden al mérito de Duarte, Sánchez y Mella, “You love the Dominican Republic and the Dominican Republic loves you.” Please find in this book messages, letters, and notes from the Dominican people. The messages come from the general public, members of the Embassy’s social media community, Embassy contacts and Embassy staff. They represent the sentiment of people from different ages, from different provinces and from different walks of life on how they viewed your time in the country and your positive impact. We hope you will cherish these memories which represent the admiration you have gained from the Dominican people throughout your service as U.S. Ambassador. Como siempre y para siempre, Estamos Unidos. - U.S. Embassy Santo Domingo Public Affairs Section 4 5 Visit to Fundación Pediátrica por un Mañana - Dec. 2018 7 8 9 10 11 Visit to Ciudad Santamaría - Dec. 2018 Visit to Ciudad Santamaría - Dec. 2018 13 14 15 "Baseball! ¡Béisbol!" mobile exhibit - Nov. 2019 17 18 19 20 21 Independence Day celebration - July 2019 23 24 25 26 27 Visit to Dream Project, Cabarete - Nov. 2018 29 30 31 32 Visit of Secretary of State Michael Pompeo - Aug. 2020 Laurence Martínez Muchas gracias por brindarnos tanta amabilidad Johaira Soto It was a true pleasure to meet you. -

5871-Ii Duvergé

ESQUEMA REGIONAL CUENCA CINTURÓN DE SIERRA SAN JUAN DE MAPA GEOLÓGICO DE LA REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA SERVICIO GEOLÓGICO NACIONAL -SGN- DUVERGÉ 5871-II PERALTA DE L E Y E N D A ESCALA 1:50.000 71°45'0"W 71°44'0"W 71°43'0"W 71°42'0"W 71°41'0"W 71°40'0"W 71°39'0"W 71°38'0"W 71°37'0"W 71°36'0"W 71°35'0"W 71°34'0"W 71°33'0"W 71°32'0"W 71°31'0"W 71°30'0"W NEIBA 19 Limos, arenas y gravas, aluviones del sistema hidrográfico actual LA DESCUBIERTA (5871-I) 15 11 18 Coluviones y cuaternario indiferenciado 17 210 211 18°30'0"N 212 213 214 215 216 217 I' 218 219 220 221 222 223 II' 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 CUENCA 17 Conos aluviales activos 18°30'0"N 19 16 2047 DE 16 Zona mareal del Lago Enriquillo 13 6 6 N 2 Q1-3 SIERRA HOLOCENO 15 Arena de playas actuales del Lago Enriquillo 17 Q 4 ENRIQUILLO 14 10 2047 BARBARITA 70 O I 14 Margas, arenas y limos lacustres del Lago Enriquillo 15 DE R 15 Q 4 A M. GARCÍA 13 13 Horizonte con formaciones de algas y encostramientos estromatolíticos N 4 EL ARENAZO Q 16 Q 4 0 R 12 Canales arrecifales, arrecifes y margas del lago Enriquillo E 18 14 Q 4 T 9 11 Margas lacustres en zonas inundables (Laguna El Limón y ISLA CABRITOS Villa Jaragua 2046 A 12 U Laguna En Medio) SIERRA C 10 Margas y calizas lacustres en zonas de margen previamente 2046 ROBERTO cubiertas por agua (decantación) 18°29'0"N 4 N 2 Q1-3 DE SONADOR 18°29'0"N PLEISTOCENO 8 9 Caliza lacustre con gasterópodos 8 Conglomerados con clastos, calizas y arcillas rojas, molasa sintectónica 2045 Q 1-3 BAHORUCO 7 7 Alterita, arcillas y gravas en dolinas de la Sierra de Bahoruco 5 15 Q 4 6 Fm. -

Puerto Escondido

MAPA GEOLÓGICO DE LA REPÚBLICA DOMINICANA ESCALA 1:50.000 Puerto Escondido (5870-I y 5870-IV) Santo Domingo, R.D., Enero 2007-Diciembre 2010 República Dominicana Consorcio IGME-BRGM-INYPSA Cartografía geotemática Proyecto SYSMIN II - 01B Enero 2007/Diciembre 2010 La presente Hoja y Memoria forma parte del Programa de Cartografía Geotemática de la República Dominicana, Proyecto 1B, financiado, en consideración de donación, por la Unión Europea a través del programa SYSMIN II de soporte al sector geológico-minero (Programa CRIS 190-604, ex No 9 ACP DO 006/01). Ha sido realizada en el periodo 2007-2010 por el Bureau de Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM), formando parte del Consorcio IGME-BRGM-INYPSA, con normas, dirección y supervisión del Servicio Geológico Nacional, habiendo participado los siguientes técnicos y especialistas: CARTOGRAFÍA GEOLÓGICA, COORDINACIÓN Y REDACCIÓN DE LA MEMORIA - Dr Marc Joubert (BRGM) - Dr Fernando Pérez Varela (Universidad de Jaén, España) - Dr Manuel Abad de Los Santos (Universidad de Huelva, España) MICROPALEONTOLOGÍA Y PETROGRAFÍA DE ROCAS SEDIMENTARIAS - Dra. Chantal Bourdillon (ERADATA, Le Mans, Francia) SEDIMENTOLOGÍA Y LEVANTAMIENTO DE COLUMNAS - Dr Manuel Abad de Los Santos (Universidad de Huelva, España) - Dr Fernando Pérez Varela (Universidad de Jaén, España) PETROGRAFÍA DE ROCAS SEDIMENTARIAS - Dra. Chantal Bourdillon (ERADATA, Le Mans, Francia) GEOLOGÍA ESTRUCTURAL Y TECTÓNICA - Dr Marc Joubert (BRGM) - Dr. Javier Escuder Viruete (IGME) GEOMORFOLOGÍA - Dr Fernando Moreno (INYPSA) MINERALES METÁLICOS Y NO METÁLICOS - Ing. Eusebio Lopera (IGME) TELEDETECCIÓN - Ing. Juan Carlos Gumiel (IGME) INTERPRETACIÓN DE LA GEOFÍSICA AEROTRANSPORTADA - Dr. José Luis García Lobón (IGME) DIGITALIZACIÓN, CREACIÓN DE LA ESTRUCTURA SIG Y EDICIÓN DE LOS MAPAS República Dominicana Consorcio IGME-BRGM-INYPSA Cartografía geotemática Proyecto SYSMIN II - 01B Enero 2007/Diciembre 2010 - Ing. -

Ricordii 2017 Grupo Jaragua-Tgedit

Conservation of Ricord´s Iguana (Disney Conservation Fund Project) Report submitted by Rick Hudson (IIF) and Co-PI-s Ernst Rupp and Andrea Thomen (Grupo Jaragua) October 2016 to October 2017 Photo A1: Planting of Almácigo seedling on the Southern Shore of Lake Enriquillo Photo A2: Field technician José Luis installing trail camera Photo A3: One-year-old Ricord´s Iguana Photo A5: Juvenile C. ricordii at its den and in front of an Alpargata cactus. Note how its color intermingles with the surroundings. Photo A6: Ricord's Iguana by photographer Rafael Arvelo Overview and Objectives of Project Ricord´s Iguana (Cyclura ricordii) is considered Critically Endangered according to the IUCN Red List. Three subpopulations of the species are found within the Jaragua-Bahoruco-Enriquillo Biosphere Reserve in the Dominican Republic. Since 2003 Grupo Jaragua has been involved in the conservation of the species and has monitored the two most vulnerable populations, one in the Pedernales area and the other one on the southern shore of Lake Enriquillo. The main goal of the project is to ensure the long-term survival of C. ricordii throughout its natural range by protecting, maintaining, restoring a diversity of high quality native habitats and establishing community based management for wild C. ricordii populations with the following components: 1. Restoration planting of 21,000 cladodes of Alpargata (Consolea moniliformis) and 3,000 saplings of Guayacan (Guaiacum officinale) in the Southern Shore of Enriquillo Lake and Pedernales. 2. Habitat monitoring and vigilance of the total area of presence of the species in Pedernales and the Southern Shore of Lake Enriquillo. -

Pearly-Eyed Thrasher) Wayne J

Urban Naturalist No. 23 2019 Colonization of Hispaniola by Margarops fuscatus Vieillot (Pearly-eyed Thrasher) Wayne J. Arendt, María M. Paulino, Luis R. Pau- lino, Marvin A. Tórrez, and Oksana P. Lane The Urban Naturalist . ♦ A peer-reviewed and edited interdisciplinary natural history science journal with a global focus on urban areas ( ISSN 2328-8965 [online]). ♦ Featuring research articles, notes, and research summaries on terrestrial, fresh-water, and marine organisms, and their habitats. The journal's versatility also extends to pub- lishing symposium proceedings or other collections of related papers as special issues. ♦ Focusing on field ecology, biology, behavior, biogeography, taxonomy, evolution, anatomy, physiology, geology, and related fields. Manuscripts on genetics, molecular biology, anthropology, etc., are welcome, especially if they provide natural history in- sights that are of interest to field scientists. ♦ Offers authors the option of publishing large maps, data tables, audio and video clips, and even powerpoint presentations as online supplemental files. ♦ Proposals for Special Issues are welcome. ♦ Arrangements for indexing through a wide range of services, including Web of Knowledge (includes Web of Science, Current Contents Connect, Biological Ab- stracts, BIOSIS Citation Index, BIOSIS Previews, CAB Abstracts), PROQUEST, SCOPUS, BIOBASE, EMBiology, Current Awareness in Biological Sciences (CABS), EBSCOHost, VINITI (All-Russian Institute of Scientific and Technical Information), FFAB (Fish, Fisheries, and Aquatic Biodiversity Worldwide), WOW (Waters and Oceans Worldwide), and Zoological Record, are being pursued. ♦ The journal staff is pleased to discuss ideas for manuscripts and to assist during all stages of manuscript preparation. The journal has a mandatory page charge to help defray a portion of the costs of publishing the manuscript.