Harness Racing, Group Identity, and the Creation of a Maine-New Brunswick Sporting Region, 1870-1930

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cowl As a New Candidate, Does Tenure Guarantee," Asked Should Insure Successful Bicentennial and Was Actually His Class' Vice See DRANS

THl Vol. XXIX No. 3 Wednesday. February 4, 1976 12 Pages AAUP Backs Drans Appeal By Bruce Antonelll tenure. Drans contends that the With the legal and financial newer policy stated in the Faculty support of the American Manual does not apply to him. Association of University Drans lost his case in Superior Professors, Jean-Yves Drans, a Court in November of last year professor of French, will appeal his because, said the Court, although suit against Providence College to "it is clear from the record that the Rhode Island Supreme Court. there was no compulsory It has been nearly five years retirement age at Providence since Professor Drans first College until 1969," the contract questioned the College's man• signed by Drans in 1970 (after the datory retirement age of 65 years. promulgation of the new policy) In 1974 he f.ied suit in Rhode Island superceded the 1969 contract Superior Court contesting this between the parties (in which the policy Drans, now 64, sought a old policy was presumably still in declaratory judgement to the ef• effect!. Drans decided in fect that he is not bound by the December to file an appeal with retirement rule announced in the the R.I. Supreme Court. Faculty Manual in September of The professor meanwhile 1969. Cowl Photo by Jim Muldoon brought his case to the national A typical set of apartment houses on Oakland Avenue in Providence. According to Father John Mc- Drans joined the faculty in 1948, office of the American Association Mahon of Student Affairs, more and more PC students are moving off-campus each year to gain "experience" one of a small group of lay in• of University Professors in and improve study habits. -

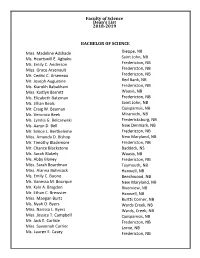

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019

Faculty of Science Dean's List 2018-2019 BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Miss. Madeline Adshade Dieppe, NB Ms. Heartswill E. Agbaku Saint John, NB Ms. Emily C. Anderson Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace Arsenault Fredericton, NB Mr. Cedric C. Arseneau Fredericton, NB Mr. Joseph Augustine Red Bank, NB Ms. Kiarokh Babakhani Fredericton, NB Miss. Kaitlyn Barrett Waasis, NB Ms. Elizabeth Bateman Fredericton, NB Ms. Jillian Beals Saint John, NB Mr. Craig W. Beaman Quispamsis, NB Ms. Veronica Beek Miramichi, NB Ms. Lyndia G. Belczewski Fredericksburg, NB Ms. Aaryn D. Bell New Denmark, NB Mr. Simon L. Bertheleme Fredericton, NB Miss. Amanda D. Bishop New Maryland, NB Mr. Timothy Blackmore Fredericton, NB Mr. Chance Blackstone Baddeck, NS Ms. Sarah Blakely Waasis, NB Ms. Abby Blaney Fredericton, NB Miss. Sarah Boardman Taymouth, NB Miss. Alanna Bohnsack Hanwell, NB Ms. Emily C. Boone Beechwood, NB Ms. Vanessa M. Bourque New Maryland, NB Mr. Kyle A. Bragdon Riverview, NB Mr. Ethan C. Brewster Hanwell, NB Miss. Maegan Burtt Burtts Corner, NB Ms. Nyah D. Byers Wards Creek, NB Miss. Narissa L. Byers Wards, Creek, NB Miss. Jessica T. Campbell Quispamsis, NB Mr. Jack E. Carlisle Fredericton, NB Miss. Savannah Carrier Lorne, NB Ms. Lauren E. Casey Fredericton, NB Mr. Kevin D. Comeau Mr. Nicholas F. Comeau Miss Emma M. Connell BACHELOR OF SCIENCE Ms. Jennifer Chan Fredericton, NB Mr. Benjamin Chase Fredericton, NB Mr. Matthew L. Clinton Fredericton, NB Miss. Grace M. Coles North Milton, PE Ms. Emma A. Collings Montague, PE Mr. Jordan W. Conrad Dartmouth, NS Mr. Samuel R. Cookson Quispamsis, NB Ms. Kelsey E. -

Don't Be Shut Out!

FRIDAY, JANUARY 11, 2019 ©2019 HORSEMAN PUBLISHING CO., LEXINGTON, KY USA • FOR ADVERTISING INFORMATION CALL (859) 276-4026 Horses, Health Keep Anette Lorentzon Busy DON’T BE SHUT OUT! From a professional standpoint, 2018 was a very solid year for trainer Anette Lorentzon. Her 739 starters in 2018 banked enter now for the hottest sale this winter $2,247,362 in purses, topping her 2017 money-winnings of $2,188,191 from 651 starts. Personally, 2018 was a very difficult year for Lorentzon and her family. Her father, John Erik Magnusson, was killed in a farming accident in July. Anette’s father founded ACL JGS Photo Farm and she trains and races the farm’s many homebreds. Then in December Anette, just February 12 & 13, 2019 35, underwent surgery to re- pair her femur. The procedure ENTER ONLINE NOW was required because of prior www.bloodedhorse.com surgery on her femur when she was diagnosed with can- ENTRIES CLOSING SOON! cer several years ago. “They said the cement that holds the bone together had Anette fallen apart so I had to have a Lorentzon new femur,” shared Lorent- zon. “The femur was sup- “There’s No Substitute for Experience” posed to last 15 years, but mine obviously didn’t. The JERRY HAWS • P.O. Box 187 • Wilmore, Kentucky 40390 cement that held it all in place fell apart.” Phone: (859) 858-4415 • Fax: (859) 858-8498 Lorentzon has been fitting physical therapy into her busy schedule with her other responsibilities. She has 55 horses in training at the family’s ACL Farm in Paris, Ky., and her sis- WHAT’S INSIDE . -

Industrial Park

VILLAGE OF PERTH-ANDOVER, N.B. Village of WH ET ERE P LS ME Perth-Andover EOPLE AND T RAI Perth-Andover Industrial Park "Home of the Best Power Rates in New Brunswick” CONTACT Mr. Dan Dionne Chief Administrative Officer Village of Perth-Andover 1131 West Riverside Drive Perth-Andover, New Brunswick E7H 5G5 Telephone: (506) 273-4959 Facsimile: (506) 273-4947 Email: [email protected] Website: www.perth-andover.com HISTORY OVERVIEW In 1991 the municipality established a 25 acre block of land for an industrial Perth-Andover is located on the Saint John River, 40 kilometres south of park. Several businesses have established themselves in the Industrial Grand Falls near the mouth of the Tobique River. Perth is located on the Park, and the municipality is currently expanding the park to accommodate east side of the river and Andover is located on the west side. The two future demand. Businesses wishing to establish in the park can expect the villages were amalgamated in 1966 and have a population service area in Mayor and Council to do whatever possible to assist them. Perth-Andover excess of 6,000 people. Nestled between the rolling hills of the upper river is ideally located for businesses looking for excellent access to the United valley, this picturesque village is often referred to as the "Gateway to the States and to Ontario and Quebec. Combine this with an excellent quality of Tobique". The Municipality is ten kilometres west of the U.S. border and life and you have one of the most attractive areas in the province for approximately 80 kilometres north of Woodstock and the entrance to locating new industry. -

New Sweden, Westmanland, Madawaska Lake, Stockholm, Woodland, Perham, & Caribou PB

1870 -2010 Maine Swedish Colony MIDSOMMAR 18-20 June, 2010 Friday-Sunday Maine Midsommar Festival m n.co unca lliamLD 1870 ©2009 Wi Free Souvenir Calendar, Guide, and Map Maine Swedish Colony: New Sweden, Westmanland, Madawaska Lake, Stockholm, Woodland, Perham, & Caribou PB Local Banking since 1936! Keep your money at Home, where it helps build AROOSTOOK our Community. Monday-Saturday • Swedish Specialty Foods SAVINGS & LOAN 10:00 AM – 5:30 PM • Scandinavian Sweaters [email protected] • Crystal Dinnerware Aroostook County Federal • Clogs • Jewelry • Platinum Troll Beads Dealer Your Home Bank Savings and Loan Association • Table Linens • Bridal Registry FDIC Insured Equal Housing Lender PB Places to stay Places To Eat Caribou Within the Colony Burger Boy . Sweden Street . .498-2291 * Fieldstone Cabins and RV Park, Madawaska Lake Burger King . Bennett Drive . 498-3500 * Aunties Cabin, New Sweden, 207-896-7905 Delivering on Cindy’s Sub Shop . Sweden Street . .498-6021 * Up North Cabins, New Sweden (+camping & trailer sites) 207- Far East Kitchen . Bennett Drive . 493-7858 896-3328 SM Farm's Bakery . 118 Bennett Drive . 493-4508 * Paul Bondeson camping, New Sweden, 207-896-5553 A promise. Frederick’s South Side . South Main St. .498-3464 Greenhouse Restaurant . Rt. 1 & 164 . 498-3733 Caribou Houlton Farms Dairy (about 10 minutes south of New Sweden) (Ice Cream) . Bennett Drive . 498-8911 * Old Iron Inn B&B, 207-492-4766, 4 bedrooms Jade Palace Restaurant . Skyway Plaza, * Russell’s Motel, 207-498-2567, 14 units . Bennett Drive . 498-3648 * Caribou Inn and Convention Center, 73 rooms, McDonald’s . Bennett Drive . 498-2181 207-498-3733, Napoli's . -

Annual Report 2015 HORSE SPORT IRELAND Annual Report 2015 HORSE SPORT IRELAND

HORSE SPORT IRELAND Annual Report 2015 HORSE SPORT IRELAND Annual Report 2015 HORSE SPORT IRELAND Department of Department Department of Culture, Arts & of Transport Agriculture, Food Structures Leisure (NI) Tourism & Sport and the Marine Fédération Sport Northern Irish Sports Equestre Olympic Council Paralympic Ireland (SNI) Council (ISC) Internationale of Ireland (OCI) Council of Ireland (FEI) HSI Sport Sub Horse Sport Ireland (HSI) HSI Breeding Board Board of Directors Sub Board HSI Affiliate Organisations in 2015 Irish Horse Board, Northern Ireland Horse Board, Connemara Army Equitation School Pony Breeders Society Association of Irish Riding Clubs & Irish Pony Society Association of Irish Riding Establishments Carriage Driving Section of HSI Dressage Ireland HSI High Eventing Ireland HSI Finance HSI Rules Performance Committee Committee Federation of Irish Polo Clubs Structures Hunting Association of Ireland Irish Harness Racing Club Irish Long Distance Riding Association Irish Polocrosse Association Horse Sport Ireland – What We Do Irish Pony Club Irish Pony Society Interface with the Government and Government agencies on behalf of the sector. Irish Quarter Horse Association Irish Shows Association Act as the national governing body for equestrian sport as recognised by the Fédération Equestre Internationale (FEI), Irish Irish Universities Riding Clubs Association Sports Council (ISC), Olympic Council of Ireland (OCI) and Sport Medical Equestrian Association NI (SNI). Mounted Games Association of Ireland Maintain the Irish Horse Register which incorporates the Irish Para Equestrian Ireland Sport Horse (ISH) and Irish Draught Horse (IDH) studbooks, under licence from the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Pentathlon Ireland Marine. Riding for the Disabled Association Ireland Issue identification (ID) documents for horses under licence from Royal Dublin Society the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. -

Fredericton Trail Guide Guide Des Sentiers De Fredericton

Trails / Sentiers Fredericton Trail Guide Information Explore Over 120 kms of Trails! Trail Visitor Centre, 180 Station Road, (May - October) / Centre des visiteurs du sentier, 180, ch. Station (mai - octobre), 506-460-2023 Guide des sentiers de Thanks to our Coalition Members: Trans Canada Trail Foundation / Remerciement aux membres de la Coalition : Fondation du Sentier transcanadien, TcTrail.ca Fredericton Outdoor Enthusiasts of Fredericton, Découvrez plus de 120 km OutdoorEnthusiasts.weebly.com City of Fredericton / Ville de Fredericton de sentiers! Capital City Road Runners, CCRR.ca 506-460-2020, Fredericton.ca Wostawea Ski Club, Wostawea.ca Fredericton Trails Coalition / Folks On Spokes, Coalition des sentiers de Fredericton facebook.com/FolksonSpokesFredericton 2021-2022 FrederictonTrailsCoalition.com Thanks to our sponsors: PO Box 3715 / C.P. 3715 Remerciement aux commanditaires : Station B / Succursale B Fredericton, NB / Fredericton (N-B) E3A 5L7 The Fredericton Trails Coalition shall be the community Fredericton.ca TourismFredericton.ca voice for the promotion of an environmentally - friendly Fredericton.ca transportation network and recreational trail system that aims to enhance the health and quality of life for those who live in and visit our city. La Coalition des sentiers de Fredericton se veut la voix de la communauté pour la promotion d’un réseau de transport écologique et de sentiers récréatifs dans le but d’améliorer la Picaroons.ca Wostawea.ca RadicalEdge.ca santé et la qualité de vie de ceux et celles qui demeurent ici ou qui visitent notre ville. TrailwayBrewing.com Trail Etiquette / Savages.ca Règles de civisme dans les sentiers : WheelsAndDeals.ca • Obey all signs / Respecter la signalisation. -

SOILS of the WOODSTOCK - FLORENCEVILLE AREA CARLETON COUNTY, NEW BRUNSWICK VOLUME 1 New Brunswick Soil Survey Report No

SOILS OF THE WOODSTOCK - FLORENCEVILLE AREA CARLETON COUNTY, NEW BRUNSWICK VOLUME 1 New Brunswick Soil Survey Report No. 14 Agriculture I 9 I Canada Research Branch Y L SOILS OF THE WOODSTOCK - FLORENCEVILLE AREA - CARLETON COUNTY, NEW BRUNSWICK :- VOLUME 1 New Brunswick Soi1 Survey Report No. 14 Sherif H. Fahmy and Herbert W. Rees Land Resource Research Centre Fredericton, New Brunswick LRRC Contribution No. 88-85 Research Branch Agriculture Canada 1989 - +,.’ > \ ERRATA - Please correct the following errors: 1. in table 7 pages 19 and 25 under drainage replace a11“NS” by “U”, 2. on the bottom of pages 18 to 31 (i.e.,: key to table) under - Drainage, Deer, Ripping add: “S = Severe to very severe limitation” and “U = Unsuitable”, - Farm Roads replace: “S = Severe to very severe limitation” by “S = Suitable” ! J ii Copies of tlis report are available froc Agriculture Canada LRRC, Soil Survey Unit P.O. Box 20280 Fredericton Research Station Fredericton, N.B. E3B 427 New Brunswick Department of Agriculture P.O. Box 6OW Fredericton, N.B. E3B 5Hl Caver photograph: Carleton Soi1 Landscape (Photo: Karel Michalica, NBDA) . L 111 -Listoffigunsandtabks. ................................................................................................................................................................. iv AckIKnvledgments. ............................................................................................................................................................................... V S- ............................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Curriculum Vitae

ROBERT CVORNYEK, Ph.D. Florida State University Holly Building A111-A Panama City, Florida 32408 [email protected] CURRICULUM VITAE EDUCATION Ph.D. History, Columbia University, 1993 M.Phil. History, Columbia University, 1981 M.A. History, University of Akron, 1978 B.A. Political Science, University of Delaware, 1975 TEACHING/ADMINISTRATIVE EXPERIENCE Professor of History/Secondary Rhode Island College 2008-Present Education Interim Department Chair/ Rhode Island College Spring 2016 Department of Educational Studies Chair/History Rhode Island College 2008-2014 Associate Professor of History/ Secondary Education Rhode Island College 2002-2008 Assistant Chair/History 2002-2008 Interim Associate Dean/ Feinstein School of Education Rhode Island College 2000-2002 Assistant Professor of History/ Secondary Education Rhode Island College 1993-2000 Assistant Professor of History Rhode Island College 1990-1993 NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION Faculty Athletic Representative Rhode Island College 2012-Present RELATED EXPERIENCE Consultant/Co-Curator Rhode Island College. Exhibit Curator for “The Providence Steamroller: Providence’s Football Tradition,” October 1-31, 2018, Adams Library, Providence, Rhode Island. Rhode Island PBS. Writer/Consultant for WSBE production on race, community, and sports in Rhode Island, 2015-present. Providence City Archives. Contributed text and images for an exhibit at Providence City Hall titled “Baseball in Providence,” May 2015. Museum of African American History. Co-Curator and Principal Scholar for an exhibit titled “The Color of Baseball: The History of Black Teams, the Players, and a Sporting Community,” Boston, Massachusetts, May 10-October 31, 2012. New York Yankees. Contributed text and images and edited final manuscript for an exhibit at Yankee Stadium titled “Reaching the Pinnacle: Yankee Stadium and Negro League Baseball.” January 2009. -

FROM the HORSE's MOUTH Spirit Open Equestrian Program Newsletter November/December 2015

FROM THE HORSE'S MOUTH Spirit Open Equestrian Program Newsletter November/December 2015 Calendar of Events Ride4SPIRIT - 11/14 10a.m. Abilities Expo – 12/4-6 Season’s Greetings & Happy Holidays from SPIRIT Silent Auction & Social at Kalypso in Reston – 12/12 Dear Friends, 5p.m. – 9p.m. As we enter the holiday season and reflect on the moments that made this year so Winter Dressage Series – special, we are so grateful for your friendship. This was a year of wonderful 1/23/16, 2/27/16, accomplishments. You made these moments possible and brought joy to so many! 3/12/16, 4/30/16 We wish you joy and peace and look forward to a very Happy New Year! Winter Sessions – ~ Dada & the SPIRIT Team 1/18/16 – 2/8/16, 2/22/16-3/7/16 Summer Camps – 6/20/16 – 6/24/16, 6/27/16 – 7/1/16, 8/15/16 – 8/19/16, The Year in Review 8/22/16 – 8/26/16 Thank you to everyone for making 2015 one of our best years! It may be tough to remember back to those cold and snowy days in January but SPIRIT has grown and shone throughout the year! Our achievements in 2015 will carry SPIRIT into 2016 with hope, courage and strength! SPIRIT Board Our SPIRIT family increased in our number of clients and service hours! We renewed our existing contract with the Fairfax County Park Authority (FCPA) for the next 7 years! We Welcomes 1 More! received a new contract with the Community Service Act (CSA). -

Feed Grain Transportation and Storage Assistance Regulations

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Feed Grain Transportation and Règlement sur l’aide au Storage Assistance Regulations transport et à l’emmagasinage des céréales C.R.C., c. 1027 C.R.C., ch. 1027 Current to November 21, 2016 À jour au 21 novembre 2016 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (3) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (3) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. publié, sauf preuve contraire. -

OTL Summer 2006.PUB

A publication of the Society for American Baseball Research Business of Baseball Committee Volume XII Issue 2 Summer2006 Why is THAT Executive a Hall of Famer? From the Editor Have You Seen His Leadership Stats? By Steve Weingarden, Christian Resick (Florida Interna- The theme of this issue of Outside the Lines is Business of tional University) and Daniel Whitman (Florida Interna- Baseball at SABR 36. Most of the presenters with topics tional University) involving the business of baseball at SABR 36 in Seattle have agreed to recast their presentations as articles for this With another Baseball Hall of Fame induction ceremony and the fall issues of Outside the Lines. now complete, many ecstatic fans have witnessed their en- dorsed candidates immortalized in bronze. As always, fans The set of articles presented here from SABR 36 approach will passionately debate whether or not those enshrined business of baseball from a number of disciplines— actually belong in the hall and will also grumble over psychology, history, geography, American studies, law and which players were snubbed. When compared to their statistics. They reflect the breadth of inquiry in our corner “player-debating” counterparts, those baseball fans pas- of baseball research. We thank each of the authors for their sionately debating which executives should and should not contribution to our understanding of the game. be in the Hall of Fame are relatively less conspicuous. Per- haps some of this can be attributed to the fact that players The only piece not presented in Seattle is an analysis by are measured in so many statistical categories and can be Gary Gillette and Pete Palmer of interleague play and the compared easily while executive performance, in MLB, is MLB’s claims of its significant impact on attendance.