Children's Lexical Knowledge of English in Flanders and the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philippines Arrests Kuwaiti Terror Suspect, Syrian Wife

‘Eagle Resolve’; Chelsea edge Kuwait, US hold towards title; military exercise4 Hazard45 shines Min 20º Max 32º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 17191 - Friday, April 7, 2017 Philippines arrests Kuwaiti terror suspect, Syrian wife Page 9 MANILA: Kuwaiti national (2nd left) and Syrian national (2nd right) are escorted by National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) personnel after a press conference in Manila yesterday. — AFP Local FRIDAY, APRIL 7, 2017 Local Spotlight Local VIEWPOINT No more licenses for expats A Make-up Society: Depression loneliness because they are just too scared to tell the directions at peak times. I also do not know By Sana Kalim truth. And the blinding truth is that: They can’t cope. By Muna Al-Fuzai the objective of enlarging roundabouts They are not strong. The sun doesn’t look like it has without traffic lights to organize traffic flow! [email protected] been lovingly crafted for them just to see them hap- If we want to reduce the number of vehi- py. Sure, there are times where their makeup cakes cles, we should have an alternative, such as off though; these are the times where they say “I do how to develop public transportation, con- [email protected] uwait, this oasis within the hostility of the not want to live”, or “I will say goodbye in a few trol taxis, and build a metro, because we all world, was thought to be the epitome of hap- moments.” Most of the time, these statements are know that taxi services are not fully effective piness. Sadly this is not the case. -

Netanyahu Formally Denies Charges in Court

WWW.JPOST.COM THE Volume LXXXIX, Number 26922 JERUSALEFOUNDED IN 1932 M POSTNIS 13.00 (EILAT NIS 11.00) TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2021 27 SHVAT, 5781 Eye in the sky A joint goal Feminist religious art IAI unveils aerial Amos Yadlin on the need to When God, Jesus surveillance system 6 work with Biden to stop Iran and Allah were women Page 6 Page 9 Page 16 How did we miss Netanyahu formally denies charges in court Judges hint witnesses to be called only after election • PM leaves hearing early the exit • By YONAH JEREMY BOB two to three weeks to review these documents before wit- Prime Minister Benjamin nesses are called, that would ramp? Netanyahu’s defense team easily move the first witness fought with the prosecution beyond March 23. ANALYSIS on Monday at the Jerusalem Judge Rivkah Friedman Feld- • By YONAH JEREMY BOB District Court over calling man echoed the prosecution’s witnesses in his public cor- arguments that the defense A lifetime ago when living ruption trial before the March had between one to two years in northern New Jersey, I 23 election. to prepare for witnesses. But often drove further north for It seemed that the judges ultimately the judges did not work. were leaning toward calling seem anxious to call the first Sometimes the correct exit the first witness in late March witness before March 23. was small and easy to miss. or early April, which they A parallel fight between the But there were around five would present as a compro- sides was the prosecution’s or so exits I could use to avoid mise between the sides. -

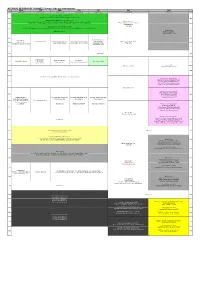

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July(Easiness)

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL Program Schedule July(easiness) MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN 6.13.20.27 7.14.21.28 1.8.15.22.29 2.9.16.23.30 3.10.17.24.31 4.11.18.25 5.12.19.26 Supercars/Technology(1st~3rd) Megafactories、Top Gear USA Season3、Strippers: Cars For Cash 400 400 NATGEO WILD HOUR(6th~21st、30th、31st) Witness Disaster Animal Genius、Superpride、Animal Fight Club、Ninja Shrimp、Return of The Clouded Leopards、Speed Kills、 →Next Megaquake(11th ~6:00) Search For The Giant Octopus、Sixgill Shark: Into the Abyss、Humpbacks: Cracking The Code、Sloth Bears →Megafactories →Car SOS PADI presents Marine Week(22nd~28th) 430 Secrets of The Mediterranean、Sharks of Lost Island、One Ocean、Seas Strangest Square Mile、Fur Seals: Battle For Survival 430 Military Hour Zeb's River Journey Taiwan's Frog Men →Bugging Hitler's Army 500 500 Inside: Talibanistan、 Storm Worlds、 Top Gear Season2 Seconds From Disaster 5、 Seconds From Disaster VI、 THE BORDER、 Witness: Disaster In Japan War Generals、 Inside Combat Rescue Convoy: War For The Atlantic Nazi Death Camp: →Car SOS The Man Who Saved The World The Great Escape 530 530 600 information 600 Brain Games 4、 Science of Stupid、 Do Or Die、 630 Hacking The System Do Or Die、 Grand Mama's Boy 630 Brain Games 2 None of The Above Season 2 Danger Decoded Car Sos III Top Gear Season2 →Top Gear USA Season4 700 700 Is it Real?、Scam City、UFOs: The Untold Stories2 、Invasion Earth Entertain Your Brain Special Hacking The System[Restaurant Ruses] 730 /Hacking The System[Travel Tricks] 730 /Hacking The System[Holiday Hacks] /Hacking The System[Survival Hacks] Highway Thru Hell 2 Entertain Your Brain Special Brain Games 4 [Peer Pressure] 800 /Do Or Die[Killer Tsunami!] 800 /Do Or Die[Fire In The Sky] Wingsuit Daredevil、 NATGEO WILD HOUR(1st) NATGEO WILD HOUR(2nd) NATGEO WILD HOUR(3rd) /Danger Decoded[#1] Inside Maritime Singapore、 Animals Gone Wild Animal Genius Animal Genius Inside: The Shanghai Bund、 Don't Tell My Mother 4 The Lost Diary of Dr. -

ELAINE HOWARD ECKLUND Rice University Sociology Department, MS-28 P.O

ELAINE HOWARD ECKLUND Rice University Sociology Department, MS-28 P.O. Box 1892 Houston, TX 77251-1892 Phone: 713-348-6761 Email: [email protected] August 1, 2019 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2013-Present Herbert S. Autrey Chair in Social Sciences, School of Social Sciences, Rice University. 2013-Present Professor, Department of Sociology, Rice University. 2011-2013 Associate Professor, Department of Sociology, Rice University. 2008-2011 Assistant Professor, Sociology Department, Rice University. 2006-2008 Assistant Professor, Sociology Department, University at Buffalo, SUNY. 2004-2006 Postdoctoral Fellow, Sociology Department, Rice University. ACADEMIC LEADERSHIP 2018-2019 President, Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2010-Present Founding Director, Religion and Public Life Program, Rice University. 2017-Present Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Sociology, Rice University. 2013-2015 Director, Boniuk Institute for the Study and Advancement of Religious Tolerance, Rice University. 2011-2014 Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Sociology, Rice University. 2008-2009 Associate Director, Center on Race, Religion, and Urban Life, Rice University. AFFILIATE ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS AND HONORS 2018 Gifford Lecturer, University of Edinburgh, Scotland 2018-Present Faculty Affiliate, Chao Center for Asian Studies, Rice University. 2014-Present Faculty Affiliate, Department of Religion, Rice University. 2010-Present Rice Scholar, James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. EDUCATION 2001-2004 Ph.D., Sociology, Cornell University, August, 2004. 2001-2002 Visiting Graduate Student Fellow, Princeton University. 1998-2001 MA, Sociology, Cornell University, January, 2001. 1991-1995 BS, Human Development, Cornell University, May, 1995. MAJOR GRANTS 2018-2020 Ecklund, Elaine Howard, PI (Christopher P. Scheitle, Co-PI), “Religion-Related Bias Victimization: Addressing a Blind-Spot,” National Science Foundation ($249,998, Grant #1753972). -

Science of Stupid

Forces Science of Stupid We are going to watch a clip from National Geographic, Science of Stupid, where we will see how gravity, resistance, and gradient affect acceleration. Task: as we watch, complete the True or False activity. If false, right the correct answer below in the space provided. True / False 1. Wheels build up speed when going downhill due to gravitational acceleration. 2. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ True / False Wheels have low rolling resistance, meaning that they do not pose much opposition to gravity’s pull. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ True / False 3. The steeper the hill, the smaller the acceleration. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ True / False 4. To stay balanced, you must keep your centre of mass above the narrow base of support (i.e. the wheels) - if you move your centre of mass outside of the base of support, you will become unbalanced. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ True / False 5. A sudden hit of resistance will make you slow down gradually. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ True / False 6. A wider base of support and a lower centre of mass makes something less stable. ____________________________________________ ____________________________________________ Forces Science of Stupid We are going to watch a clip from National Geographic, Science of Stupid, where we will see how gravity, resistance, and gradient affect acceleration. Answers 1. Wheels build up speed when going downhill due to gravitational acceleration. 2. Wheels have low rolling resistance, meaning that they do not pose much opposition to gravity’s pull. 3. The steeper the hill, the greater the acceleration. 4. To stay balanced, you must keep your centre of mass above the base of support (e.g. -

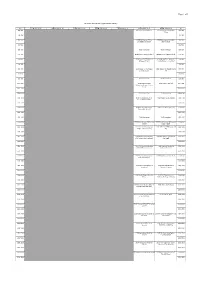

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule February

Page 1 of 5 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC Program Schedule February (ET) 月曜日 2020/01/27 火曜日 2020/01/28 水曜日 2020/01/29 木曜日 2020/01/30 金曜日 2020/01/31 土曜日 2020/02/01 日曜日 2020/02/02 (ET) 400-430 04:00 War Generals[Part 2] 04:00 Apocalypse World War 400-430 I[Rage] 430-500 430-500 500-530 05:00 War Heroes of The 05:00 Apocalypse World War 500-530 Skies[Battle of Britain] I[Deliverance] 530-600 530-600 600-630 06:00 information 06:00 information 600-630 630-700 06:30 Science of Stupid 3[#11] 06:30 Science of Stupid 3[#12] 630-700 700-730 07:00 Cesar To The Rescue 07:00 Wicked Tuna: North vs. 700-730 2[Raging Pit Bull] South 2[Down To The Wire] 730-800 730-800 800-830 08:00 Cesar To The Rescue 08:00 Alaska Fish Wars[#1 Game 800-830 2[Twice Bitten] On] 830-900 830-900 900-930 09:00 information 09:00 information 900-930 930-1000 09:30 Europe's Great 09:30 PHOTO ARK[#2] 930-1000 Wildernesses[Europe's Green Heart] 1000-1030 1000-1030 1030-1100 10:30 information 10:30 information 1030-1100 1100-1130 11:00 The Incredible Dr. Pol 11:00 Hostile Planet[Deserts] 1100-1130 Season 6[Mamma Mia!] 1130-1200 1130-1200 1200-1230 12:00 The Incredible Dr. Pol 12:00 Hostile Planet[Oceans] 1200-1230 Season 6[K-9 To 5] 1230-1300 1230-1300 1300-1330 13:00 information 13:00 information 1300-1330 1330-1400 13:30 Primal Survivor 3[Crocodile 13:30 Primal Survivor 3[Operation 1330-1400 Hunter] Deep Freeze] 1400-1430 14:00 Air Crash Investigation 14:00 CAR S.O.S.Ⅵ[Peugeot 205 1400-1430 S13[Fatal Transmission] Gti] 1430-1500 1430-1500 1500-1530 15:00 Air Crash Investigation 15:00 -

Sam Mangan ONLINE EDITOR & COLOURIST

Sam Mangan ONLINE EDITOR & COLOURIST 1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] CREDITS: Doctor Jeff: Rocky Mountain Vet Series 02 12 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Double Act TV for Discovery Super Scary Plane Landings 1 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Peacock for Channel 5 Nev’s Indian Call Centre 6 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Liberty Bell for Watch Science of Stupid Series 3 15 x 30’ Factual Entertainment IWC Media for National Geographic Mozart in London 1 x 60’ Documentary Matchlight for BBC One Imagine: David Chipperfield 1 x 60’ Documentary BBC for BBC One You’ve been A Lovely Audience 3 x 60’ Documentary Liberty Bell for BBC One My Life (Fashion Designer) 1 x 20’ Documentary CTVC for CBBC Sugar Free Farm 3 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Liberty Bell for ITV Miracle Weddings 1 x 60’ Documentary Raw TV for ITV Imagine: Shylock’s Ghost 1 x 60’ Documentary Storyvault for BBC Arts Home Away From Home Series 02 20 x 60 Factual Entertainment BBC Factual for BBC One How To Win At Everything 14 x 30’ Factual Entertainment IWC Media for National Geographic Life On Marbs 12 x 60’ Reality Entertainment Lime Pictures for ITVBe Flockstars 8 x 30’ Reality Entertainment Liberty Bell for ITV The Prince of Newton Square 1 x 90’ Documentary Raw Television Metropolis 6 x 60’ Documentary Nutopia for Travel Channel Doctor Jeff: Rocky Mountain Vet Series 01 10 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Double Act TV for Discovery Council House Crooks 5 x 60’ Factual Entertainment Shine Media for BBC The Erotic Adventures -

After 33 Years, a Diploma P.M

2014 Columbia County Serious injuries in crash, see GUIDE INSIDE below. WEEKEND EDITION FRIDAY & SATURDAY, JUNE 20-21, 2014 | YOUR COMMUNITY NEWSPAPER SINCE 1874 | 75¢ Lake City Reporter LAKECITYREPORTER.COM New principal named From staff reports elementary schools have been moted to principal at Columbia said, to give the candidate time to filled, Supt. Terry Huddleston said City. inform his or her current employer June 20 Vacant principal’s chairs at Thursday. Huddleston’s pick at Fort White Art Reception Columbia City and Fort White Hope Jernigan has been pro- will be announced Monday, he PRINCIPALS continued on 3A The community is invit- ed to a wine and cheese reception at the Gateway Art Gallery, 168 North 91 years Marion Street, from 5:30-7 After 33 years, a diploma p.m. Guest artist will be John Rice. later, cold Farmers Market The Live Oak farm- case still ers market is now open Fridays from 12-6 p.m. at unsolved John H Hale Park, 215 NE Duval Street. Bones from 1923 Dearly Departed were discovered in “Dearly Departed,” a underwater cavern. drop dead comedy by Bottrell and Jones, will show tonight at the High By MEGAN REEVES Springs Community [email protected] Theatre, 130 NE 1st Ave, High Springs. Three Lake A 91-year-old cold case has City actors will perform: the Columbia County Sheriff’s Pam Register, Shelly Office looking for answers. Dukes, and Catherine JASON MATTHEW WALKER/Lake City Reporter Jessie Preston’s supposed Summers. Tickets are Fort White resident Carlos Southers, 48, grad- Carlos Southers dropped out remains, which were found available at The Framery of uated from the Columbia Career and Adult of school to help his family. -

Ng Dark 00:55 00:55

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC - BULGARIA APRIL MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY 06:00 WILD CHRONICLES -> 11.04 DO OR DIE 06:00 06:20 I DIDN'T KNOW THAT 3 -> 06.04 STREET GENIUS 06:20 06:45 DANGER DECODED -> 13.04 SCIENCE OF STUPID 06:45 07:10 HIGHWAY THRU HELL: USA -> THE INCREDIBLE DR. POL 1 & 2 07:10 LAWLESS ISLAND 1 & 2 08:05 DEAD END EXPRESS -> 13.04 ALASKA WING MEN 1 & 2 08:05 09:00 BIG FISH TEXAS -> 20.04 BIG FIX ALASKA 09:00 09:30 BANGED UP ABROAD THE INCREDIBLE DR. POL 09:30 10:00 6 & 7 1 & 2 10:00 11:00 SECONDS FROM DISASTER 6 - > 10.04 AIR CRASH INVESTIAGATION DANGER DECODED -> 22.04 11:00 11:30 DANGEROUS ENCOUNTERS ACCESS 360 WORLD 11:30 12:00 URBAN JUNGLE - > 10.04 AIR CRASH INVESTIAGATION 12:00 12:30 12:30 13:00 NAZI MEGASTRUCTURES 13:00 13:30 13:30 14:00 BIG, BIGGER, BIGGEST 3 -> 04.04 ENGINEERING CONNECTIONS -> 27.04 MEGA BREAKDOWN 14:00 14:30 ICE ROAD RESCUE 14:30 15:00 HIGHWAY THRU HELL 2 -> 22.04 WORLD'S 15:00 16:00 HIGHWAY THRU HELL DOOMSDAY TOUGHEST FIXES 16:00 PREPPERS 2 17:00 ALASKA WING MEN 1 & 2 -> 26.04 YUKON GOLD 1 17:00 18:00 BIG FISH TEXAS -> 13.04 BIG FIX ALASKA -> 25.04 COLD WATER GOLD 18:00 19:00 19:00 20:00 20:00 ACI 16 -> 17.04 MARS RT -> 26.04 STRIPPERS: CARS FOR 20:55 ORIGINS RT CAR SOS 5 CASH RT-> 14.04 ORIGINS 20:55 PARCHED GENIUS MEGASTRUCTURES RT EARTH WEEK AIR CRASH SPECIALS -> 12.04 GEN X -> 09.04 HISTORY'S SCIENCE OF EASTER -> 22.04 21:55 CRIME LAB INVESTIGATION 15 CAR SOS 5 RT WATER & POWER: 21:55 SECRETS 2 STUPID 4 EARTH DAY -> 29.04 RT CALIFORNIA HEIST -> YEARS OF LIVING DEATH OF HITLER LAWLESS OCEANS -> 10.04 DRUGS INC. -

TVLISTINGS the LEADING SOURCE for PROGRAM INFORMATION MIP APP 2013 Layout 1 9/26/14 3:17 PM Page 1

LIST_1014_COVER_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/26/14 2:20 PM Page 1 WWW.WORLDSCREENINGS.COM OCTOBER 2014 MIPCOM EDITION TVLISTINGS THE LEADING SOURCE FOR PROGRAM INFORMATION MIP_APP_2013_Layout 1 9/26/14 3:17 PM Page 1 World Screen App UPDATED FOR MIPCOM For iPhone and iPad DOWNLOAD IT NOW Program Listings | Stand Numbers | Event Schedule | Daily News Photo Blog | Hotel and Restaurant Directories | and more... Sponsored by Brought to you by *LIST_1014_LIS_1006_LISTINGS 9/26/14 3:25 PM Page 3 TV LISTINGS 3 3 In This Issue 41 ENTERTAINMENT 500 West Putnam Ave., 4/Fl. 3 22 Greenwich, CT 06830, U.S.A. 41 Entertainment Imira Entertainment 4K Media IMPS Tel: (1-203) 717-1120 Incendo e-mail: [email protected] 4 INK Global 9 Story Entertainment A+E Networks ITV-Inter Medya website: www.41e.tv ABC Commercial AFL Productions 23 ITV Studios Global Entertainment 4K's Yu-Gi-Oh! ZEXAL 5 Kanal D Alfred Haber Distribution Keshet International all3media international Lightning Entertainment PROGRAM HIGHLIGHTS American Cinema International Yu-Gi-Oh! ARC-V: Season 1 (Animation, Animasia Studio 24 Lionsgate Entertainment Stand: R7.E59 49x30 min.) Yuya Sakaki’s dream is to become 6 m4e/Telescreen Contact: Allen Bohbot, mng. dir.; Kiersten the greatest “duel-tainer” in history–and he APT Worldwide MarVista Entertainment Armoza Formats MediaBiz Morsanutto, sales & mktg. mgr.; Francisco just might pull it off when he discovers a nev- ARTE France Urena, prod. brand assurance dir. er-before-seen technique that lets him sum- Artear 25 & MediaCorp mon many monsters at once. 7 Mediatoon Distribution Artist View Entertainment Miramax Atlantyca Entertainment Mondo TV S.p.A. -

UPV Celebrates Women's Month

March - April 2015 UPViews 1 Vol. 19 No. 2 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF U.P. VISAYAS March - April 2015 Read UPViews online at www.upv.edu.ph UPV celebrates Women’s Month A VARIETY of events and programs for the month-long celebration of Women’s Month in March was organized by the UP Visayas Gender and Development Program in partnership with UGSAD, a Western Visayas Regional Gender Resource Center. The March 6, 2015 Purple Caravan from Plaza Libertad to the Iloilo Provincial Capitol kicked-off the festivities. This L-R: 1)Atty. Hiballes of IBP (top) addresses women rights advocates during the public forum. 2) Chancellor Espinosa (right) was followed by an opening receives a token from GDP Dir. Badayos-Jover. 3) Atty. Hiballes likewise leads the ribbon-cutting for the opening of Women Bazaar program at the Capitol after which and Exhibits at the Iloilo City campus. medical services for women were services group. A public forum on the role also very much involved in the provided by a women’s health The induction of the new set of women as decision makers celebration of Women’s Month of offi cers of the National was held on March 11 at the UP through the “Student Orgs Fair” Network on Women in Fisheries Visayas auditorium. Atty. Maricar on March 12-13, which was Gallaza leads (WINFISH) was also held the Villanueva-Hiballes, president- held simultaneously at the UPV same day at Diversion 21 Hotel. elect of the Integrated Bar of Miagao and Iloilo City campuses. UPHSI On March 8, 2015, the the Philippines-Iloilo Chapter On March 16, 17, 19, and Municipality of Oton, Iloilo served as the resource person. -

Documentary – Factual

DANIEL TAYLOR DUBBING MIXER 1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA 44-48 Bloomsbury Street, London, WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Documentary – Factual Great Ormond Street 1 x 60’ Films of Record for BBC Two Grand Designs: House of the Year 3 x 60 Boundless for Channel 4 The Autistic Gardener 2 x 60' Betty TV for Channel 4 Life and Death Row: Love Triangle 8 x 10' BBC Three What a Performance! Pioneers of Popular Entertainment 1 x 60 Liberty Bell for BBC 4 Dr Jeff: Rocky Mountain Vet 4 x 60' Double Act for Discovery Survival in the Skies 1 x 60 Arrow Media for Smithsonian Channel End of the World Night 1 x 90' Oxford Film and Television for Channel 4 Meet the Devotees 1 x 25' BBC Three Metropolis 2 x 60 Nutopia for Travel Channel Science of Stupid 35 x 30' IWC for National Geographic What Britain Bought in 2016 1 x 60' Sundog Pictures for Channel 4 Hidden Histories: Britain’s Oldest Family Businesses 3 x 60’ Raw TV for BBC Four The Fabulous Baker Brothers: A Bite of Britain 6 x 60' Betty TV for Discovery My Phone Sex Secrets 1 x 60’ Back2back Productions for Channel 4 Embarrassing Bodies: The Man with Half a Face 1 x 60’ Maverick TV for Channel 4 Children of the Revolution 1 x 75’ Nayanaya Pictures Good Morning Rocinha 1 x 60' TVE For Al-Jazeera The Crane Gang 2 x 60’ Liberty Bell for BBC Two Black Ops 2 x 60’ World Media Rights for Discovery Katie: The Science of Seeing Again 1 x 60’ Mentorn Media for Channel 4 Food Inspectors 1 x 60' Betty TV for BBC One Shocking Breastfeeding 1 x 60' Betty TV