Avian Reactions Towards Human Approaches in Different Urban Greenery Structures in Nanaimo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Birding Tour South Africa: Western Cape Custom Tour

BIRDING TOUR SOUTH AFRICA: WESTERN CAPE CUSTOM TOUR 8-12 OCTOBER 2016 By Chris Lotz Orange-breasted Sunbird (photo John Tinkler) www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Western Cape custom tour October 2016 ITINERARY Date (2016) Location Overnight 8-Oct Cape Town to Tankwa Karoo Sothemba Lodge, Tankwa 9-Oct Full day in the Karoo Sothemba Lodge, Tankwa 10-Oct Tankwa Karoo to the Overberg Mudlark River Front Lodge 11-Oct Agulhas Plains Mudlark River Front Lodge 12-Oct Betty's Bay and Rooiels (back in Cape Town) Day 1: 8 October 2016 I fetched Robert and Elizabeth from Hotel Verde at Cape Town International Airport at 7:30 a.m., and we immediately started heading toward the amazingly endemic-rich Tankwa Karoo. But we had lots of birding to do before getting to the Karoo. En route we stopped in the famous Cape wine town of Paarl for an hour or two, as Paarl boasts some excellent birding sites and is perfectly right on the way to the Karoo. Just as we entered Paarl we were glad to be able to stop for a pale-phase Booted Eagle soaring above us – we actually ended up seeing a good number of this small eagle throughout our tour. After admiring the eagle we headed for the botanical garden within the Paarl Mountain Nature Reserve, where we got acquainted with a bunch of fynbos endemics and other goodies. This trip proved excellent for raptors. As we arrived at the botanical garden, we saw a Black Harrier hunting, then later we got amazingly close views of a perched African Goshawk – a two-accipiter morning is always a good morning! Three species of beautiful sunbirds were much in evidence: Malachite, Southern Double-collared, and Orange-breasted Sunbirds. -

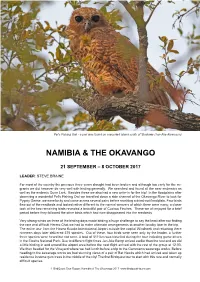

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Coleoptera: Lampyridae)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-03-23 Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Martin, Gavin Jon, "Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae)" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8895. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8895 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Seth M. Bybee, Chair Marc A. Branham Jamie L. Jensen Kathrin F. Stanger-Hall Michael F. Whiting Department of Biology Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Gavin Jon Martin All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin Department of Biology, BYU Doctor of Philosophy Fireflies are a cosmopolitan group of bioluminescent beetles classified in the family Lampyridae. The first catalogue of Lampyridae was published in 1907 and since that time, the classification and systematics of fireflies have been in flux. Several more recent catalogues and classification schemes have been published, but rarely have they taken phylogenetic history into account. Here I infer the first large scale anchored hybrid enrichment phylogeny for the fireflies and use this phylogeny as a backbone to inform classification. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Describing Species

DESCRIBING SPECIES Practical Taxonomic Procedure for Biologists Judith E. Winston COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 1999 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © Winston, Judith E. Describing species : practical taxonomic procedure for biologists / Judith E. Winston, p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-231-06824-7 (alk. paper)—0-231-06825-5 (pbk.: alk. paper) 1. Biology—Classification. 2. Species. I. Title. QH83.W57 1999 570'.1'2—dc21 99-14019 Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 98765432 p 10 98765432 The Far Side by Gary Larson "I'm one of those species they describe as 'awkward on land." Gary Larson cartoon celebrates species description, an important and still unfinished aspect of taxonomy. THE FAR SIDE © 1988 FARWORKS, INC. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Universal Press Syndicate DESCRIBING SPECIES For my daughter, Eliza, who has grown up (andput up) with this book Contents List of Illustrations xiii List of Tables xvii Preface xix Part One: Introduction 1 CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION 3 Describing the Living World 3 Why Is Species Description Necessary? 4 How New Species Are Described 8 Scope and Organization of This Book 12 The Pleasures of Systematics 14 Sources CHAPTER 2. BIOLOGICAL NOMENCLATURE 19 Humans as Taxonomists 19 Biological Nomenclature 21 Folk Taxonomy 23 Binomial Nomenclature 25 Development of Codes of Nomenclature 26 The Current Codes of Nomenclature 50 Future of the Codes 36 Sources 39 Part Two: Recognizing Species 41 CHAPTER 3. -

Avifauna Survey

AVIFAUNA SURVEY Prepared by: Dr W. Richard J Dean, Research Associate at the DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology at the University of Cape Town Reviewed and edited by: Dr Penn Lloyd, Principal Ecologist and Director at Biodiversity Assessment and Management Pty Ltd; and Patrick Morant, SACNASP Professional Natural Scientist (Reg. No. 401514/83). Table of content II. SURVEY RESULTS 3 III. INFRASTRUCTURE AND POTENTIAL IMPACTS ON BIRDS 10 IV. CONSERVATION RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER LONG-TERM MONITORING AND RESEARCH PROGRAMME WITHIN THE SKA CORE AREA AND KCAAA1 13 V. LIST OF ALL BIRD SPECIES RECORDED WITHIN KCAAA1 14 VI. REFERENCES 22 I. Introduction The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) is situated in the Nama Karoo, so only those bird species that occur in the Nama Karoo will be discussed here. The study area of the strategic environmental assessment (SEA) for the first phase of the SKA project (SKA1_MID) covers 153 Quarter Degree Grid Cells (QDGC)1, fairly well covered by participants in the Bird Atlas project in the late 1980s and early 1990s with lists of bird species for all 153 QDGC. Data for the 153 QDGC are a combination of the South African Bird Atlas Project data, museum specimen data and sight data (WRJD pers. obs.) and includes a recent bird list compiled by Etienne Marais. The avifauna of the Nama Karoo is not distinctive, and there are no families of birds endemic to the Karoo, but there are 25 species that are near-endemic to the region (Table 1). Only two species, Red Lark Calendulauda burra and Sclater's Lark Spizocorys sclateri, whose distribution ranges are almost entirely within the Nama Karoo, can be considered true endemics to the Nama Karoo. -

Climatic Effects on Niche Evolution in a Passerine Bird Clade Depend on Paleoclimate Reconstruction Method

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.14209 Climatic effects on niche evolution in a passerine bird clade depend on paleoclimate reconstruction method Alison Eyres,1,2,3,4 Jussi T. Eronen,5,6 Oskar Hagen,7,8 Katrin Böhning-Gaese,1,2 and Susanne A. Fritz1,2,9 1Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Frankfurt 60325, Germany 2Department of Biological Sciences, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt 60438, Germany 3RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, United Kingdom 4E-mail: [email protected] 5Ecosystems and Environment Research Program and Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS), Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, Helsinki 00014, Finland 6BIOS Research Unit, Helsinki 00170, Finland 7Landscape Ecology, Institute of Terrestrial Ecosystems, D-USYS, ETH Zürich, Zürich CH-8092, Switzerland 8Swiss Federal Research Institute WSL, Birmensdorf CH-8903, Switzerland 9Institut für Geowissenschaften, Goethe University Frankfurt, Frankfurt 60438, Germany Received August 7, 2019 Accepted February 12, 2021 Climatic niches describe the climatic conditions in which species can persist. Shifts in climatic niches have been observed to coincide with major climatic change, suggesting that species adapt to new conditions. We test the relationship between rates of climatic niche evolution and paleoclimatic conditions through time for 65 Old-World flycatcher species (Aves: Muscicapidae). We combine niche quantification for all species with dated phylogenies to infer past changes in the rates of niche evolution for temperature and precipitation niches. Paleoclimatic conditions were inferred independently using two datasets: a paleoelevation reconstruction and the mammal fossil record. We find changes in climatic niches through time, but no or weak support for a relationship between niche evolution rates and rates of paleoclimatic change for both temperature and precipitation niche and for both reconstruction methods. -

Alternatives to Taxonomic Hierarchy: the Sahaptin Case

J. Ethnobiol. 4(1): 73-92 May 1984 ALTERNATIVES TO TAXONOMIC HIERARCHY: THE SAHAPTIN CASE EUGENE S. HUNN Department ofAnthropology University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195 DAVID H. FRENCH Department ofAnthropology Reed College Portland, Oregon 97202 ABSTRACT.-The folk biological classification system of the Sahaptin-speaking Indians, a hunting-gathering people of the Columbia River Plain, is compared with other well docu mented systems. The Sahaptin system is notable for its lack of taxonomic hierarchy, especially in the rarity of binomial names. Such names imply taxonomic subordination of the binomially labeled taxon. Sahaptin speakers more frequently employ complex names which employ coordination of core and conceptually related peripheral taxa. An inventory of such names from one Sahaptin dialect group is analyzed. Explanations for the lack of hierarchy in Sahaptin folk biological classification and nomenclature are discussed. An evo lutionary Ifunctional explanation based on the relative sizes of the folk biological domains of hunter-gatherers versus subsistence agriculturalists is preferred. INTRODUCTION Studies of folk biological classification begin with the matching of names to corres ponding segments of the biota. Since they do not end there, the next step is to seek to discover and analyze the organizing principles that structure these systems, which may then be compared cross-culturally_ Berlin's universal principles of folk biological classification and nomenclature (1973: Berlin, Breedlove, and Raven 1973), though based on limited comparative data, represent a pioneering effort at such cross-cultural analysis, and provide the framework for most subsequent studies of the structure of folk biological classification systems. His proposals have been supported (e.g., BruneI 1974: Hays 1974, 1983; Hunn 1975), extended (Brown 1977: Brown et aJ. -

Essential Namibia: Custom Trip Report 10 – 19 October 2019

ESSENTIAL NAMIBIA: CUSTOM TRIP REPORT 10 – 19 OCTOBER 2019 www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Essential Namibia custom tour October 2019 Overview Namibia is a must-visit African country since it is so very unique, with the world’s oldest desert including the highest sand dunes in the world of a spectacular red color, rugged desert mountains along the bird-rich Namibian Escarpment, and one of the world’s greatest game parks, the vast Etosha National Park. And, last but not least, Namibia hosts a number of birds that are only found there or in adjacent Angola. This tour was a uniquely crafted departure searching for as many bird species as possible in central Namibia with limited time at our disposal. In terms of finding key species we did very well – locating basically all of the desired targets. A total of 218 bird species were seen (plus eight species heard only). A full bird list can be found at the end of this report. After some initial, productive birding around Windhoek and a wonderful evening in the capital the clients set off to Sossusvlei via a highly scenic charter flight over awe-inspiring dunes and rugged topography. After spending the day at the red sand sea of Sossusvlei they took another incredible flight along the Atlantic coastline, taking in Cape Fur Seal colonies and more dune scenery, to Walvis Bay, where we continued our trip. What follows in an annotated report of the key birding and wildlife localities visited as well as some of the respective highlights enjoyed at each. -

2016 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours NAMIBIA, OKAVANGO AND VICTORIA FALLS BIRD LIST NOVEMBER 2016 Bold = Southern African endemic Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CE = Critically Endangered Common name (IOC 6.4) Scientific name (IOC 6.4) Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES OstricHes Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 South African SHelducK Tadorna cana 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Cape Shoveler Anas smithii 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 Hottentot Teal Anas hottentota 1 Southern Pochard Netta erythrophthalma 1 Maccoa Duck - NT Oxyura maccoa 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 PHeasants and allies PHasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi 1 Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 SPHENISCIFORMES Penguins SpHeniscidae African Penguin - EN Spheniscus demersus 1 PROCELLARIIFORMES Petrels, SHearwaters Procellariidae Sooty Shearwater - NT Ardenna grisea 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Eagle-Eye Tours Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos PHoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias -

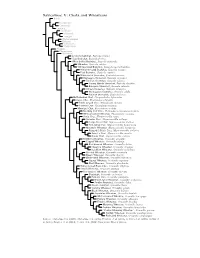

Saxicolinae Species Tree, Part 5

Saxicolinae V: Chats and Wheatears Irania Hodgsonius Cyanecula Luscinia ?Calliope Myiomela Tarsiger ?Heteroxenicus Enicurus Cinclidium Myophonus Ficedula Phoenicurus Monticola Jerdon’s Bushchat, Saxicola jerdoni Gray Bushchat, Saxicola ferreus White-bellied Bushchat, Saxicola gutturalis Whinchat, Saxicola rubetra White-browed Bushchat, Saxicola macrorhynchus White-throated Bushchat, Saxicola insignis Pied Bushchat, Saxicola caprata White-tailed Stonechat, Saxicola leucurus Stejneger’s Stonechat, Saxicola stejnegeri Siberian Stonechat, Saxicola maurus Canary Islands Stonechat, Saxicola dacotiae European Stonechat, Saxicola rubicola African Stonechat, Saxicola torquatus Madagascan Stonechat, Saxicola sibilla Reunion Stonechat, Saxicola tectes Buff-streaked Chat, Campicoloides bifasciatus Karoo Chat, Emarginata schlegelii Sickle-winged Chat, Emarginata sinuata Tractrac Chat, Emarginata tractrac Moorland Chat, Pinarochroa sordida Mocking Cliff-Chat, Thamnolaea cinnamomeiventris White-crowned Cliff-Chat, Thamnolaea coronata Sooty Chat, Myrmecocichla nigra Anteater Chat, Myrmecocichla aethiops Congo Moor Chat, Myrmecocichla tholloni Ant-eating Chat, Myrmecocichla formicivora Mountain Wheatear, Myrmecocichla monticola Rueppell’s Black Chat, Myrmecocichla melaena Arnott’s Chat, Myrmecocichla arnotti Ruaha Chat, Myrmecocichla collaris Northern Wheatear, Oenanthe oenanthe Capped Wheatear, Oenanthe pileata Red-breasted Wheatear, Oenanthe bottae Heuglin’s Wheatear, Oenanthe heuglini Isabelline Wheatear, Oenanthe isabellina Hooded Wheatear, Oenanthe monacha