Catherine the Great 1 Catherine the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 By Thomas Lucius Lowish A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Kinch Hoekstra Spring 2021 Abstract Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 by Thomas Lucius Lowish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Historians of Russian monarchy have avoided the concept of sovereignty, choosing instead to describe how monarchs sought power, authority, or legitimacy. This dissertation, which centers on Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia between 1762 and 1796, takes on the concept of sovereignty as the exercise of supreme and untrammeled power, considered legitimate, and shows why sovereignty was itself the major desideratum. Sovereignty expressed parity with Western rulers, but it would allow Russian monarchs to bring order to their vast domain and to meaningfully govern the lives of their multitudinous subjects. This dissertation argues that Catherine the Great was a crucial figure in this process. Perceiving the confusion and disorder in how her predecessors exercised power, she recognized that sovereignty required both strong and consistent procedures as well as substantial collaboration with the broadest possible number of stakeholders. This was a modern conception of sovereignty, designed to regulate the swelling mechanisms of the Russian state. Catherine established her system through careful management of both her own activities and the institutions and servitors that she saw as integral to the system. -

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR

The Changing Depiction of Prussia in the GDR: From Rejection to Selective Commemoration Corinna Munn Department of History Columbia University April 9, 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Volker Berghahn, for his support and guidance in this project. I also thank my second reader, Hana Worthen, for her careful reading and constructive advice. This paper has also benefited from the work I did under Wolfgang Neugebauer at the Humboldt University of Berlin in the summer semester of 2013, and from the advice of Bärbel Holtz, also of Humboldt University. Table of Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 2. Chronology and Context………………………………………………………….4 3. The Geschichtsbild in the GDR…………………………………………………..8 3.1 What is a Geschichtsbild?..............................................................................8 3.2 The Function of the Geschichtsbild in the GDR……………………………9 4. Prussia’s Changing Role in the Geschichtsbild of the GDR…………………….11 4.1 1945-1951: The Post-War Period………………………………………….11 4.1.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………11 4.1.2 Public Symbols and Events: The fate of the Berliner Stadtschloss…14 4.1.3 Film: Die blauen Schwerter………………………………………...19 4.2 1951-1973: Building a Socialist Society…………………………………...22 4.2.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………22 4.2.2 Public Symbols and Events: The Neue Wache and the demolition of Potsdam’s Garnisonkirche…………………………………………..30 4.2.3 Film: Die gestohlene Schlacht………………………………………34 4.3 1973-1989: The Rediscovery of Prussia…………………………………...39 4.3.1 Historiography and Publications……………………………………39 4.3.2 Public Symbols and Events: The restoration of the Lindenforum and the exhibit at Sans Souci……………………………………………42 4.3.3 Film: Sachsens Glanz und Preußens Gloria………………………..45 5. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

The Minor an Eigliteentli-Centuryfarce By

The VO Russian and East European Studies Center is proud to present The Minor an eigliteentli-centuryfarce by Denis Fonvizin HedopoCJlb ,[I;eHHca <POHBH3HHa :9Liapteaby Ju[ia Nimirovs~aya 'With Songs by'Yu[ii 1(jm fJ)irector~ 9{ptes Russia in the 18th century was known as a "woman's kingdom." During the course of almost 70 years there was a woman on the throne. Longer than any other ruled the most powerful, the most clever and educated of them all-Catherine the Great. Many Western philosophers, such as Voltaire and Diderot, considered her a truly enlightened monarch. Denis Fonvizin was the secretary of her personal enemy, Count Panin. Fonviziil wrote his most famous comedy The Minor in 1782; it is one of the 10 most famous Russian plays in the canon and one of the most frequently produced. Contemporaries read it as a criticism of female dominance and a satire on Catherine's reign, with the message that a strong woman is worse than a tyrannical man. The play's other goal was to show the audience that education improves people morally, while ignorance allows them to degrade and become mere beasts (thus the pig-loving Skotinin). In this comedy, all the educated people are kind and good, and all the uneducated people behave like animals. Of course, according to the laws of classical comedy, light and goodness con~er darkness and malice. It was not always this way in the 18t century-goodness did not always win. But we remember this century as a time of brilliant individualities, when strong personalities, eccentrics, and other talented people made their mark. -

Nineteenth-Century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia

Ezequiel Adamovsky Russia as a Space of Hope: Nineteenth-century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia Introduction Beginning with Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois, a particular perception of Russia emerged in France. To the traditional nega- tive image of Russia as a space of brutality and backwardness, Montesquieu now added a new insight into her ‘sociological’ otherness. In De l’esprit des lois Russia was characterized as a space marked by an absence. The missing element in Russian society was the independent intermediate corps that in other parts of Europe were the guardians of freedom. Thus, Russia’s back- wardness was explained by the lack of the very element that made Western Europe’s superiority. A similar conceptual frame was to become predominant in the French liberal tradition’s perception of Russia. After the disillusion in the progressive role of enlight- ened despotism — one must remember here Voltaire and the myth of Peter the Great and Catherine II — the French liberals went back to ‘sociological’ explanations of Russia’s backward- ness. However, for later liberals such as Diderot, Volney, Mably, Levesque or Louis-Philippe de Ségur the missing element was not so much the intermediate corps as the ‘third estate’.1 In the turn of liberalism from noble to bourgeois, the third estate — and later the ‘middle class’ — was thought to be the ‘yeast of freedom’ and the origin of progress and civilization. In the nineteenth century this liberal-bourgeois dichotomy of barbarian Russia (lacking a middle class) vs civilized Western Europe (the home of the middle class) became hegemonic in the mental map of French thought.2 European History Quarterly Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

On the Question of the Main Concepts and Theories of the Origin of the State

Law/1. Theory of State and Law Zhadan V. N. PhD in Law, Associate Professor Kazan Federal University, Elabuga Institute, Russia ON THE QUESTION OF THE MAIN CONCEPTS AND THEORIES OF THE ORIGIN OF THE STATE Abstract. The article is devoted to the discussion of the main concepts and theories of the origin of the state based on the analysis of General theoretical provisions of legal science, scientific approaches and author's understanding. Key words: question, basic, concept, theory, origin, state, analysis, General theoretical provisions, approaches. In the science of state and law (and especially the theory of state and law), there are many scientific materials that consider the laws of the origin, development and functioning of the state and law, historical types, forms, functions and other aspects that characterize the state and law [1-2]. Many scientists specializing in the theory of state and law (and in other areas of scientific research) offer their views on the theoretical characteristics of the state and law, their features, state-political forms and functions, and many other aspects, which does not deprive the author to Express his opinion on some issues related to the discussion of the origin of the state. The subject of this review will be questions about the main concepts and theories of the origin of the state. Based on the research subject of interest the following questions: what is a theory of the origin of the state; what the right science is called basic theory of the origin of the state; what are the terms "concept" and "theory"; which is accepted to highlight the concepts and theories of the origin of the state; how key concepts and theories explain the emergence of the state? The author shares the scientific approach that the study of theories of the origin of the state (and law) is not only cognitive (theoretical), but also political and practical in nature [3, p. -

Rabbi David Fränckel, Moses Mendelssohn, and the Beginning of the Berlin Haskalah

RABBI DAVID FRÄNCKEL, MOSES MENDELSSOHN, AND THE BEGINNING OF THE BERLIN HASKALAH. REATTRIBUTING A PATRIOTIC SERMON (1757) Addenda Gad Freudenthal On December 10, 1757, R. David Fränckel (1707–1762), Chief Rabbi of Berlin Jewry, delivered in German a sermon on the occa- sion of Frederick the Great’s victory at Leuthen five days earlier (5 December). Volume 1 of EJJS carried my article describing the genesis of this so-called “Leuthen Sermon” and established that (contrary to previous consensus) it was written by David Fränckel and not by his former student Moses Mendelssohn (1729–1796).1 Rather, it was written in Hebrew by Fränckel and only translated into German by Mendelssohn. In an appendix, I described the very rich aftermath of the sermon: after having been very elegantly translated into English (we do not know by whom) and published by the ephemeral London publisher W. Reeve in 1758, the translation was reprinted no less than four times in New England. Mr. Shimon Steinmetz from Brooklyn (N.Y.) kindly drew my attention to three earlier relevant items that had escaped my atten- tion. He also supplied copies of them. I herewith thank him warmly for his generous and erudite help and share his findings with readers of EJJS: [1] As early as March 1758, The Scots Magazine, published in Edinburgh, carried the following entry in the section “New Books”: A thanksgiving-sermon from Psal xxii. 23.24 for the King of Prussia’s victory Dec. 5. Preached on the sabbath of the 10th, in the synagogue of the Jews in Berlin. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Istanbul Bids Final Farewell to Mesrob II

MARCH 23, 2019 Mirror-SpeTHE ARMENIAN ctator Volume LXXXIX, NO. 35, Issue 4579 $ 2.00 NEWS The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 INBRIEF Guns Used by New Zealand Terrorist Had Armenian, Georgian Writing YEREVAN (Armenpress) — Armenia’s Foreign Ministry was in contact with the authorities of New Zealand regarding the note in Armenian and other languages found on one of the weapons used for the attack on the two mosques in the city of Christchurch, on Friday, March 15, MFA spokesper- son Anna Naghdalyan noted. “We are in contact with New Zealand’s relevant authorities on all issues linked with the incident,” Naghdalyan said. Brenton Tarrant, a 28-year-old Australian, was charged with the deadly attacks on two mosques in the city, which killed 50 and injured as many. One of the weapons used for the attack on the two mosques in New Zealand was covered with notes in different languages, including Armenian and Georgian, the videos released from the incident show. The Georgian state security service has already The funeral of Armenian Patriarch Mesrob II reacted to these reports, stating that it is cooperat- ing with its partners. The gun covered in white lettering featured the names of King Davit Agmashenebeli and Prince Istanbul Bids Final Farewell to Mesrob II David Soslan, the second husband of Queen Tamar, in Georgian, the Battle of Kagul 1770 (Russian- ISTANBUL (Public Radio of Armenia) referred to the Sisli Armenian cemetery in Zeytinburnu district on March 8 where he Turkish war) and the Battle of Bulair 1913 were — Archbishop Mesrob II Mutafyan, the 84th an area designated for patriarchs for burial. -

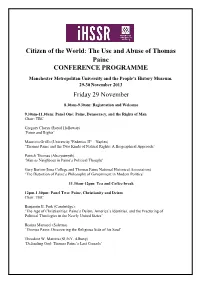

The Use and Abuse of Thomas Paine CONFERENCE PROGRAMME

Citizen of the World: The Use and Abuse of Thomas Paine CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Manchester Metropolitan University and the People’s History Museum, 29-30 November 2013 Friday 29 November 8.30am-9.30am: Registration and Welcome 9.30am-11.30am: Panel One: Paine, Democracy, and the Rights of Man Chair: TBC Gregory Claeys (Royal Holloway) ‘Paine and Rights’ Maurizio Griffo (University "Federico II" – Naples) ‘Thomas Paine and the Two Kinds of Natural Rights: A Biographical Approach’ Patrick Thomas (Aberystwyth) ‘Man as Neighbour in Paine’s Political Thought’ Gary Berton (Iona College and Thomas Paine National Historical Association) ‘The Distortion of Paine’s Philosophy of Government in Modern Politics’ 11.30am-12pm: Tea and Coffee break 12pm-1.30pm: Panel Two: Paine, Christianity and Deism Chair: TBC Benjamin E. Park (Cambridge): ‘The Age of Christianities: Paine’s Deism, America’s Identities, and the Fracturing of Political Theologies in the Newly United States’ Rosina Martucci (Salerno) ‘Thomas Paine: Discovering the Religious Side of his Soul’ Theodore W. Marotta (SUNY, Albany) ‘Defending God: Thomas Paine’s Last Crusade’ 1.30-2.30pm: Lunch 2.30pm-4pm: Panel Three: The Image and Idea of Paine in a Transatlantic Context Chair: Catherine Armstrong (MMU) Matteo Battistini (Bologna) Atlantic Fragments of Thomas Paine: Democratic Language and its Class Meaning in Paine’s Early Nineteenth Century Legacy on both the English and American Shores of the Ocean. Sam Edwards (MMU) ‘He Came From America Didn’t He? Identity, Nationality and the 1964 Thetford