Baseball and the Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Nfl Tv Plans, Announcers, Programming

NFL KICKS OFF WITH NATIONAL TV THURSDAY NIGHT GAME; NFL TV 2004 THE NFL is the only sports league that televises all regular-season and postseason games on free, over-the-air network television. This year, the league will kick off its 85th season with a national television Thursday night game in a rematch of the 2003 AFC Championship Game when the Indianapolis Colts visit the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots on September 9 (ABC, 9:00 PM ET). Following is a guide to the “new look” for the NFL on television in 2004: • GREG GUMBEL will host CBS’ The NFL Today. Also joining the CBS pregame show are former NFL tight end SHANNON SHARPE and reporter BONNIE BERNSTEIN. • JIM NANTZ teams with analyst PHIL SIMMS as CBS’ No. 1 announce team. LESLEY VISSER joins the duo as the lead sideline reporter. • Sideline reporter MICHELE TAFOYA joins game analyst JOHN MADDEN and play-by-play announcer AL MICHAELS on ABC’s NFL Monday Night Football. • FOX’s pregame show, FOX NFL Sunday, will hit the road for up to seven special broadcasts from the sites of some of the biggest games of the season. • JAY GLAZER joins FOX NFL Sunday as the show’s NFL insider. • Joining ESPN is Pro Football Hall of Fame member MIKE DITKA. Ditka will serve as an analyst on a variety of shows, including Monday Night Countdown, NFL Live, SportsCenter and Monday Quarterback. • SAL PAOLANTONIO will host ESPN’s EA Sports NFL Match-Up (formerly Edge NFL Match-Up). NFL ANNOUNCER LINEUP FOR 2004 ABC NFL Monday Night Football: Al Michaels-John Madden-Michele Tafoya (Reporter). -

Reign Men Taps Into a Compelling Oral History of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series

Reign Men taps into a compelling oral history of Game 7 in the 2016 World Series. Talking Cubs heads all top CSN Chicago producers need in riveting ‘Reign Men’ By George Castle, CBM Historian Posted Thursday, March 23, 2017 Some of the most riveting TV can be a bunch of talking heads. The best example is enjoying multiple airings on CSN Chicago, the first at 9:30 p.m. Monday, March 27. When a one-hour documentary combines Theo Epstein and his Merry Men of Wrigley Field, who can talk as good a game as they play, with the video skills of world-class producers Sarah Lauch and Ryan McGuffey, you have a must-watch production. We all know “what” happened in the Game 7 Cubs victory of the 2016 World Series that turned from potentially the most catastrophic loss in franchise history into its most memorable triumph in just a few minutes in Cleveland. Now, thanks to the sublime re- porting and editing skills of Lauch and McGuffey, we now have the “how” and “why” through the oral history contained in “Reign Men: The Story Behind Game 7 of the 2016 World Series.” Anyone with sense is tired of the endless shots of the 35-and-under bar crowd whooping it up for top sports events. The word here is gratuitous. “Reign Men” largely eschews those images and other “color” shots in favor of telling the story. And what a tale to tell. Lauch and McGuffey, who have a combined 20 sports Emmy Awards in hand for their labors, could have simply done a rehash of what many term the greatest Game 7 in World Series history. -

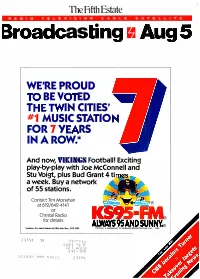

Broadcasting Ii Aug 5

The Fifth Estate R A D I O T E L E V I S I O N C A B L E S A T E L L I T E Broadcasting ii Aug 5 WE'RE PROUD TO BE VOTED THE TWIN CITIES' #1 MUSIC STATION FOR 7 YEARS IN A ROW.* And now, VIKINGS Football! Exciting play -by-play with Joe McConnell and Stu Voigt, plus Bud Grant 4 times a week. Buy a network of 55 stations. Contact Tim Monahan at 612/642 -4141 or Christal Radio for details AIWAYS 95 AND SUNNY.° 'Art:ron 1Y+ Metro Shares 6A/12M, Mon /Sun, 1979-1985 K57P-FM, A SUBSIDIARY OF HUBBARD BROADCASTING. INC. I984 SUhT OGlf ZZ T s S-lnd st-'/AON )IMM 49£21 Z IT 9.c_. I Have a Dream ... Dr. Martin Luther KingJr On January 15, 1986 Dr. King's birthday becomes a National Holiday KING... MONTGOMERY For more information contact: LEGACY OF A DREAM a Fox /Lorber Representative hour) MEMPHIS (Two Hours) (One-half TO Written produced and directed Produced by Ely Landau and Kaplan. First Richard Kaplan. Nominated for MFOXILORBER by Richrd at the Americ Film Festival. Narrated Academy Award. Introduced by by Jones. Harry Belafonte. JamcsEarl "Perhaps the most important film FOX /LORBER Associates, Inc. "This is a powerful film, a stirring documentary ever made" 432 Park Avenue South film. se who view it cannot Philadelphia Bulletin New York, N.Y. 10016 fail to be moved." Film News Telephone: (212) 686 -6777 Presented by The Dr.Martin Luther KingJr.Foundation in association with Richard Kaplan Productions. -

Download Preview

DETROIT TIGERS’ 4 GREATEST HITTERS Table of CONTENTS Contents Warm-Up, with a Side of Dedications ....................................................... 1 The Ty Cobb Birthplace Pilgrimage ......................................................... 9 1 Out of the Blocks—Into the Bleachers .............................................. 19 2 Quadruple Crown—Four’s Company, Five’s a Multitude ..................... 29 [Gates] Brown vs. Hot Dog .......................................................................................... 30 Prince Fielder Fields Macho Nacho ............................................................................. 30 Dangerfield Dangers .................................................................................................... 31 #1 Latino Hitters, Bar None ........................................................................................ 32 3 Hitting Prof Ted Williams, and the MACHO-METER ......................... 39 The MACHO-METER ..................................................................... 40 4 Miguel Cabrera, Knothole Kids, and the World’s Prettiest Girls ........... 47 Ty Cobb and the Presidential Passing Lane ................................................................. 49 The First Hammerin’ Hank—The Bronx’s Hank Greenberg ..................................... 50 Baseball and Heightism ............................................................................................... 53 One Amazing Baseball Record That Will Never Be Broken ...................................... -

University of Nebraska Press Sports

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS SPORTS nebraskapress.unl.edu | unpblog.com I CONTENTS NEW & SELECTED BACKLIST 1 Baseball 12 Sports Literature 14 Basketball 18 Black Americans in Sports History 20 Women in Sports 22 Football 24 Golf 26 Hockey 27 Soccer 28 Other Sports 30 Outdoor Recreation 32 Sports for Scholars 34 Sports, Media, and Society series FOR SUBMISSION INQUIRIES, CONTACT: ROB TAYLOR Senior Acquisitions Editor [email protected] SAVE 40% ON ALL BOOKS IN THIS CATALOG BY nebraskapress.unl.edu USING DISCOUNT CODE 6SP21 Cover credit: Courtesy of Pittsburgh Pirates II UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS BASEBALL BASEBALL COBRA “Dave Parker played hard and he lived hard. Cobra brings us on a unique, fantastic A Life of Baseball and Brotherhood journey back to that time of bold, brash, and DAVE PARKER AND DAVE JORDAN styling ballplayers. He reveals in relentless Cobra is a candid look at Dave Parker, one detail who he really was and, in so doing, of the biggest and most formidable baseball who we all really were.”—Dave Winfield players at the peak of Black participation “Dave Parker’s autobiography takes us back in the sport during the late 1970s and early to the time when ballplayers still smoked 1980s. Parker overcame near-crippling cigarettes, when stadiums were multiuse injury, tragedy, and life events to become mammoth bowls, when Astroturf wrecked the highest-paid player in the major leagues. knees with abandon, and when Blacks had Through a career and a life noted by their largest presence on the field in the achievement, wealth, and deep friendships game’s history. -

'Race' for Equality

American Journalism, 26:2, 99-121 Copyright © 2009, American Journalism Historians Association A ‘Race’ for Equality: Print Media Coverage of the 1968 Olympic Protest by Tommie Smith and John Carlos By Jason Peterson During the Summer Olympics in 1968, Tommie Smith and John Carlos made history. Although they won the gold and bronze medals, respectively, in the 200-meter dash, their athletic accom- plishments were overshadowed by their silent protest during the medal ceremony. Images of Smith and Carlos each holding up a single, closed, gloved fist have become iconic reminders of the Civil Rights movement. What met the two men after their protest was criticism from the press, primarily sportswriters. This article examines media coverage of the protest and its aftermath, and looks at how reporters dealt with Smith’s and Carlos’s political and racial statement within the context of the overall coverage of the Olympic Games. n the night of October 16, 1968, at the Olympic Games in Mexico City, U.S. sprinter Tommie Smith set a world record for the 200-meter dash by finishing O 1 in 19.8 seconds. The gold medal winner celebrated in a joyous embrace of fellow Olympian, college team- Jason Peterson is an mate, and good friend, John Carlos, who won instructor of journalism the bronze medal. However, Smith and Carlos at Berry College and a had something other than athletic accolades or Ph.D. candidate at the University of Southern the spoils of victory on their minds. In the same Mississippi, Box 299, year the Beatles topped the charts with the lyr- Rome, GA 30149. -

Cubs Daily Clips

November 4, 2016 ESPNChicago.com From 1908 until now: Cubs' run of heartache finally ends By Bradford Doolittle We want to say this all began in 1945 because a colorful tavern owner tried to drag a smelly goat named Murphy with him to a World Series game. We then employ what Joe Maddon likes to call "outcome bias" as proof of this alleged curse, bringing up such hobgoblins as the black cat in 1969, Leon Durham's glove in 1984 and Steve Bartman's eager hands in 2003. In reality, this began long before any of that. It started with a poor soul named Fred Merkle, in the year 1908 -- the last time the Chicago Cubs won a World Series. On Wednesday night, the 2016 Cubs put an end date on that cursed year by winning the franchise's first World Series in 108 years, beating the Cleveland Indians in extra innings in Game 7, 8-7. The reasons the Cubs didn't win it all for so long aren't easy to distill in a work less than book length. There are a few wide-umbrella factors that one can easily point to. With the 2016 World Series over after a stunning comeback from Chicago's North Siders, there's a good reason to revisit those factors. A very good reason in fact: They no longer exist. HOW IT STARTED There is an old book called "Baseball's Amazing Teams" by a writer named Dave Wolf. The book chronicles the most interesting team from each decade of the 20th century. -

A Summer Wildfire: How the Greatest Debut in Baseball History Peaked and Dwindled Over the Course of Three Months

The Report committee for Colin Thomas Reynolds Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: A Summer Wildfire: How the greatest debut in baseball history peaked and dwindled over the course of three months APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Co-Supervisor: ______________________________________ Tracy Dahlby Co-Supervisor: ______________________________________ Bill Minutaglio ______________________________________ Dave Sheinin A Summer Wildfire: How the greatest debut in baseball history peaked and dwindled over the course of three months by Colin Thomas Reynolds, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May, 2011 To my parents, Lyn & Terry, without whom, none of this would be possible. Thank you. A Summer Wildfire: How the greatest debut in baseball history peaked and dwindled over the course of three months by Colin Thomas Reynolds, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 SUPERVISORS: Tracy Dahlby & Bill Minutaglio The narrative itself is an ageless one, a fundamental Shakespearean tragedy in its progression. A young man is deemed invaluable and exalted by the public. The hero is cast into the spotlight and bestowed with insurmountable expectations. But the acclamations and pressures are burdensome and the invented savior fails to fulfill the prospects once imagined by the public. He is cast aside, disregarded as a symbol of failure or one deserving of pity. It’s the quintessential tragedy of a fallen hero. The protagonist of this report is Washington Nationals pitcher Stephen Strasburg, who enjoyed a phenomenal rookie season before it ended abruptly due to a severe elbow injury. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Letter to collector and introduction to catalog ........................................................................................ 4 Auction Rules ............................................................................................................................................... 5 January 31, 2018 Major Auction Top Ten Lots .................................................................................................................................................. 6-14 Baseball Card Sets & Lots .......................................................................................................................... 15-29 Baseball Card Singles ................................................................................................................................. 30-48 Autographed Baseball Items ..................................................................................................................... 48-71 Historical Autographs ......................................................................................................................................72 Entertainment Autographs ........................................................................................................................ 73-77 Non-Sports Cards ....................................................................................................................................... 78-82 Basketball Cards & Autographs ............................................................................................................... -

Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’S Concussion Problem

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2016 No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem Jeffrey Parker Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Criminology Commons, Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Health Policy Commons, Mass Communication Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Public Relations and Advertising Commons, Social Influence and oliticalP Communication Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sports Studies Commons, and the Television Commons Recommended Citation Parker, Jeffrey, "No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem" (2016). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1800. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1800 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No More Mind Games: Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’s Concussion Problem by Jeffrey Parker B.A. (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2013 THESIS Submitted to the Department of Criminology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Master of Arts in Criminology Wilfrid Laurier University © Jeffrey Parker 2015 ii Abstract American (gridiron) football played at the professional level in the National Football League (NFL) is an inherently physical spectator sport, in which players frequently engage in significant contact to the head and upper body. -

Pioneer Las Vegas Bowl Sees Its Allotment of Public Tickets Gone Nearly a Month Earlier Than the Previous Record Set in 2006 to Mark a Third-Straight Sellout

LAS VEGAS BOWL 2016 MEDIA GUIDE A UNIQUE BLEND OF EXCITEMENT ian attraction at Bellagio. The world-famous Fountains of Bellagio will speak to your heart as opera, classical and whimsical musical selections are carefully choreo- graphed with the movements of more than 1,000 water- emitting devices. Next stop: Paris. Take an elevator ride to the observation deck atop the 50-story replica of the Eiffel Tower at Paris Las Vegas for a panoramic view of the Las Vegas Valley. For decades, Las Vegas has occupied a singular place in America’s cultural spectrum. Showgirls and neon lights are some of the most familiar emblems of Las Vegas’ culture, but they are only part of the story. In recent years, Las Vegas has secured its place on the cultural map. Visitors can immerse themselves in the cultural offerings that are unique to the destination, de- livering a well-rounded dose of art and culture. Swiss artist Ugo Rondinone’s colorful, public artwork Seven Magic Mountains is a two-year exhibition located in the desert outside of Las Vegas, which features seven towering dayglow totems comprised of painted, locally- sourced boulders. Each “mountain” is over 30 feet high to exhibit the presence of color and expression in the There are countless “excuses” for making a trip to Las feet, 2-story welcome center features indoor and out- Vegas, from the amazing entertainment, to the world- door observation decks, meetings and event space and desert of the Ivanpah Valley. class dining, shopping and golf, to the sizzling nightlife much more. Creating a city-wide art gallery, artists from around that only Vegas delivers. -

Obituary Index 3Dec2020.Xlsx

Last First Other Middle Maiden ObitSource City State Date Section Page # Column # Notes Naber Adelheid Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 9/26/1928 1 3 Naber Anna M. Carrollton Gazette Patriot Carrolton IL 9/23/1960 1 2 Naber Bernard Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 11/17/1910 1 6 Naber John B. Carrollton Gazette Carrolton IL 6/13/1941 1 1 Nace Joseph Lewis Carthage Republican Carthage IL 3/8/1899 5 2 Nachtigall Elsie Meler Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 3/27/1909 15 1 Nachtigall Henry C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 11/30/1909 18 4 Nachtigall William C. Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 10/5/1925 38 3 Nacke Mary Schleper Effingham Democrat Effingham IL 8/6/1874 3 4 Nacofsky Lillian Fletcher Chicago Daily News Chicago IL 2/22/1922 29 1 Naden Clifford Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1990 Countywide 2 2 Naden Earl O. Waukegan News Sun Waukegan IL 11/2/1984 7A 4 Naden Elizabeth Broadbent Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 1/17/1900 8 4 Naden Isaac Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 2/28/1900 4 1 Naden James Darby Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/25/1935 4 5 Naden Jane Green Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 4/10/1912 9 3 Naden John M. Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 9/13/1944 5 4 Naden Martha Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 12/6/1866 3 1 Naden Obadiah Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 11/8/1911 1 1 Naden Samuel Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 6/17/1942 7 1 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/15/1878 4 3 Naden Samuel Mrs Kendall County Journal Yorkville IL 8/8/1878 1 4 Naden Thomas Kendall County