Content Analysis of In-Game Commentary of the National Football League’S Concussion Problem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2004 Nfl Tv Plans, Announcers, Programming

NFL KICKS OFF WITH NATIONAL TV THURSDAY NIGHT GAME; NFL TV 2004 THE NFL is the only sports league that televises all regular-season and postseason games on free, over-the-air network television. This year, the league will kick off its 85th season with a national television Thursday night game in a rematch of the 2003 AFC Championship Game when the Indianapolis Colts visit the Super Bowl champion New England Patriots on September 9 (ABC, 9:00 PM ET). Following is a guide to the “new look” for the NFL on television in 2004: • GREG GUMBEL will host CBS’ The NFL Today. Also joining the CBS pregame show are former NFL tight end SHANNON SHARPE and reporter BONNIE BERNSTEIN. • JIM NANTZ teams with analyst PHIL SIMMS as CBS’ No. 1 announce team. LESLEY VISSER joins the duo as the lead sideline reporter. • Sideline reporter MICHELE TAFOYA joins game analyst JOHN MADDEN and play-by-play announcer AL MICHAELS on ABC’s NFL Monday Night Football. • FOX’s pregame show, FOX NFL Sunday, will hit the road for up to seven special broadcasts from the sites of some of the biggest games of the season. • JAY GLAZER joins FOX NFL Sunday as the show’s NFL insider. • Joining ESPN is Pro Football Hall of Fame member MIKE DITKA. Ditka will serve as an analyst on a variety of shows, including Monday Night Countdown, NFL Live, SportsCenter and Monday Quarterback. • SAL PAOLANTONIO will host ESPN’s EA Sports NFL Match-Up (formerly Edge NFL Match-Up). NFL ANNOUNCER LINEUP FOR 2004 ABC NFL Monday Night Football: Al Michaels-John Madden-Michele Tafoya (Reporter). -

Andrea Kremer Named Winner of Prestigious Pete Rozelle

Honor the Heroes of the Game, Preserve its History, Promote its Values & Celebrate Excellence EVERYWHERE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 06/13/2018 ANDREA KREMER NAMED WINNER OF PRESTIGIOUS PETE ROZELLE RADIO-TELEVISION AWARD MULTI-EMMY AWARD WINNER TO BE HONORED DURING 2018 ENSHRINEMENT WEEK POWERED BY JOHNSON CONTROLS CANTON, OHIO – Andrea Kremer has been named the 2018 recipient of the prestigious Pete Rozelle Radio-Television Award. The award, presented annually by the Pro Football Hall of Fame, recognizes “longtime exceptional contributions to radio and television in professional football.” Kremer will be honored during the 2018 Enshrinement Week Powered by Johnson Controls at the Enshrinees’ Gold Jacket Dinner in downtown Canton on Friday, Aug. 3 and presented with the award at the 2018 Enshrinement Ceremony on Saturday, August 4 in Tom Benson Hall of Fame Stadium. Kremer (@Andrea_Kremer) is regarded as one of the most accomplished journalists in the industry. Her illustrious journalism career has been recognized by numerous awards and honors including two Emmys and a Peabody. She was named one of the 10 greatest female sportscasters of all-time; and described by TV Guide as “among TV’s best sports correspondents of either sex.” Kremer is currently Chief Correspondent for the NFL Network and led the network’s coverage on health and safety. She contributes critically acclaimed stories for HBO's "Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel" and is also a co-host of “WE NEED TO TALK,” the first ever all-female nationally televised weekly sports show on CBS. Kremer earned the reputation for breaking news stories and investigative pieces on social issues as they relate to sports. -

2018-19 Northern Kentucky Men's Basketball Game Notes

2018-19 NORTHERN KENTUCKY MEN’S BASKETBALL GAME NOTES No. 14 Northern Kentucky vs. No. 3 Texas Tech Schedule March 22, 2019 | 1:30 p.m. (ET) Date Opponent Time (ET)/Result Tulsa, Okla. | BOK Center (17,996) October TV/Broadcast: TNT Oct. 30 Thomas More (Ex.) W, 84-47 Brad Nessler (PxP) | Steve Lavin (Color) | Jim November Jackson (Color) | Evan Washburn (Sideline) Nov. 6 Wilmington^ W, 102-38 26-8 Overall, 13-5 Horizon League Radio: ESPN1530 (1530 AM) 26-6 Overall, 14-4 Big 12 Nov. 9 @ Northern Illinois W, 88-85 (2ot) Jim Kelch (PxP) | Steve Moeller (Color) Nov. 11 Wabash W, 99-59 Nov. 16 UNC Asheville^ W, 77-50 Last Game Starters Nov. 17 Manhattan^ W, 59-53 Nov. 18 Coastal Carolina^ W, 89-83 Nov. 24 @ UCF L, 53-66 11 12 15 32 34 Nov. 27 @ Morehead State W, 93-71 Nov. 30 UMBC W, 78-60 December Dec. 4 @ Cincinnati L, 65-78 Dec. 8 @ Eastern Kentucky L, 74-76 Dec. 16 Miami (Ohio) W, 72-66 Dec. 20 Northern Illinois W, 65-62 Jalen Trevon Tyler Dantez Drew Dec. 28 IUPUI* W, 92-77 Tate Faulkner Sharpe Walton McDonald Dec. 30 UIC* W, 73-58 R-So. Fr. Jr. Jr. Sr. January 14.0 PPG 4.9 PPG 14.1 PPG 11.1 PPG 19.1 PPG Jan. 3 @ Oakland* L, 74-76 4.4 RPG 2.5 RPG 3.1 RPG 5.5 RPG 9.5 RPG Jan. 5 @ Detroit Mercy* W, 95-73 4.1 APG 1.1 APG 1.9 APG 2.7 APG 2.9 APG Jan. -

Handbook of Sports and Media

Job #: 106671 Author Name: Raney Title of Book: Handbook of Sports & Media ISBN #: 9780805851892 HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA LEA’S COMMUNICATION SERIES Jennings Bryant/Dolf Zillmann, General Editors Selected titles in Communication Theory and Methodology subseries (Jennings Bryant, series advisor) include: Berger • Planning Strategic Interaction: Attaining Goals Through Communicative Action Dennis/Wartella • American Communication Research: The Remembered History Greene • Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory Hayes • Statistical Methods for Communication Science Heath/Bryant • Human Communication Theory and Research: Concepts, Contexts, and Challenges, Second Edition Riffe/Lacy/Fico • Analyzing Media Messages: Using Quantitative Content Analysis in Research, Second Edition Salwen/Stacks • An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research HANDBOOK OF SPORTS AND MEDIA Edited by Arthur A.Raney College of Communication Florida State University Jennings Bryant College of Communication & Information Sciences The University of Alabama LAWRENCE ERLBAUM ASSOCIATES, PUBLISHERS Senior Acquisitions Editor: Linda Bathgate Assistant Editor: Karin Wittig Bates Cover Design: Tomai Maridou Photo Credit: Mike Conway © 2006 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2009. To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk. Copyright © 2006 by Lawrence Erlbaum Associates All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by photostat, microform, retrieval system, or any other means, without prior written permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Handbook of sports and media/edited by Arthur A.Raney, Jennings Bryant. p. cm.–(LEA’s communication series) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Good Signs, Bad Signs

C M Y K D7 DAILY 10-28-07 MD BD D7 CMYK The Washington Post x B Sunday, October 28, 2007 D7 RedskinsGameday By Gene Wang 1 REDSKINS (4-2) VS. PATRIOTS (7-0) 4:15 P.M. AT GILLETTE STADIUM » TV: WTTG-5, WBFF-45 » RADIO: WWXX (92.7 FM), WWXT (94.3 FM), WBIG (100.3 FM), WXTR (730 AM) » LINE: Patriots by 16 ⁄2 REDSKINS ROSTER FIRST DOWN SECOND DOWN THIRD DOWN FOURTH DOWN PATRIOTS ROSTER No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. Ball Control Rough Up Randy Pressure Brady Crowd Control No. Player Pos. Ht. Wt. 4 Derrick Frost P 6-4 208 The Patriots have perhaps the NFL’s Wide receiver Randy Moss is in the Patriots quarterback Tom Brady has The fans at Gillette Stadium are going 3 Stephen Gostkowski PK 6-1 210 6 Shaun Suisham PK 6-0 205 best passing attack, so it will be midst of a career resurgence since thrown 27 touchdown passes and two to be charged up to see their team at 6 Chris Hanson P 6-2 202 8 Mark Brunell QB 6-1 217 important for the Redskins to win time joining the Patriots in the offseason. interceptions thanks to plenty of time home for the first time in three weeks. 7 Matt Gutierrez QB 6-4 230 15 Todd Collins QB 6-4 228 of possession and keep New England’s Moss has caught passes in double- in the pocket. Brady has been sacked The Patriots played their past two 10 Jabar Gaffney WR 6-1 200 17 Jason Campbell QB 6-5 233 offense off the field. -

NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl Has Grown to Become One of the Largest Sports Spectacles in the United States

/ The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Chelsea Police Thesis Advisor Mr. Neil Behrman Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2016 Expected Date of Graduation May 2016 §pCoJI U ncler.9 rod /he. 51;;:, J_:D ;l.o/80J · Z'7 The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making ~0/G , PG.5 Abstract Originally known as the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl has grown to become one of the largest sports spectacles in the United States. Cities across the cotintry compete for the right to host this prestigious event. The reputation of such an occasion has caused an increase in demand and price for tickets, making attendance nearly impossible for the average fan. As a result, the National Football League has implemented free events for local residents and out-of-town visitors. This, along with broadcasting the game, creates an inclusive environment for all fans, leaving a lasting legacy in the world of professional sports. This paper explores the growth of the Super Bowl from a novelty game to one of the country' s most popular professional sporting events. Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I would like to thank my parents for their unending support. Thank you for allowing me to try new things and learn from my mistakes. Most importantly, thank you for believing that I have the ability to achieve anything I desire. Second, I would like to thank my brother for being an incredible role model. -

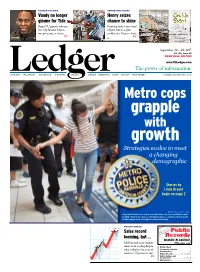

Metro Cops Grapple with Growth Strategies Evolve to Meet a Changing Demographic

CLIMER COLUMN Vandy no longer gimme for Tide Bama-VU game is relevant, but only because Mason was given time to thrive. TENNESSEE TITANS P17 Henry seizes chance to shine Running back controversy? DAVIDSONLedger • WILLIAMSON • RUTHERFORD • CHEATHAM WILSON SUMNER• ROBERTSON • MAURY • DICKSONMaybe, • MONTGOMERY but it’s a great problem for Titans to have. AP P27 See our ad on page 12 September 22 – 28, 2017 The power of information.NASHVILLE Vol. 43 EDITION | Issue 38 www.TNLedger.com Metro cops FORMERLY WESTVIEW SINCE 1978 grapple Page 13 Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: with Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, www.westviewonline.com TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore,Dec.: Melinda Atty: Bryce L Tomlinson, Coatney, Resp.: growth Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 Strategies evolve to meetInsurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, Def Atty(s): J Brent Moore, 08/26/2010, 10C3316 10P1321 Dec.: -

Versatile Fox Sports Broadcaster Kenny Albert Continues to Pair with Biggest Names in Sports

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Erik Arneson, FOX Sports Wednesday, Sept. 21, 2016 [email protected] VERSATILE FOX SPORTS BROADCASTER KENNY ALBERT CONTINUES TO PAIR WITH BIGGEST NAMES IN SPORTS Boothmates like Namath, Ewing, Palmer, Leonard ‘Enhance Broadcasts … Make My Job a Lot More Fun’ Teams with Former Cowboy and Longtime Broadcast Partner Daryl ‘Moose’ Johnston and Sideline Reporter Laura Okmin for FOX NFL in 2016 With an ever-growing roster of nearly 250 teammates (complete list below) that includes iconic names like Joe Namath, Patrick Ewing, Jim Palmer, Jeremy Roenick and “Sugar Ray” Leonard, versatile FOX Sports play-by-play announcer Kenny Albert -- the only announcer currently doing play-by-play for all four major U.S. sports (NFL, MLB, NBA and NHL) -- certainly knows the importance of preparation and chemistry. “The most important aspects of my job are definitely research and preparation,” said Albert, a second-generation broadcaster whose long-running career behind the sports microphone started in high school, and as an undergraduate at New York University in the late 1980s, he called NYU basketball games. “When the NFL season begins, it's similar to what coaches go through. If I'm not sleeping, eating or spending time with my family, I'm preparing for that Sunday's game. “And when I first work with a particular analyst, researching their career is definitely a big part of it,” Albert added. “With (Daryl Johnston) ‘Moose,’ for example, there are various anecdotes from his years with the Dallas Cowboys that pertain to our games. When I work local Knicks telecasts with Walt ‘Clyde’ Frazier on MSG, a percentage of our viewers were avid fans of Clyde during the Knicks’ championship runs in 1970 and 1973, so we weave some of those stories into the broadcasts.” As the 2016 NFL season gets underway, Albert once again teams with longtime broadcast partner Johnston, with whom he has paired for 10 seasons, sideline reporter Laura Okmin and producer Barry Landis. -

Buy Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys

Buy Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,NHL Jerseys,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Nike Eagles Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps Online Save 70% Off,Free Shipping We Are One Of The Jerseys Wholesaler.Sonny Vaccaro,the so-called godfather concerning grassroots basketball,cheap nfl jersey, checked everywhere in the providing some one TrueHoop?¡¥s Henry Abbott for more information regarding point on the town that going to be the Team USA all of these just won gold along going to be the FIBA World Championships consisted generally having to do with players who didn?¡¥t are going to want for additional details on play a lot of those university basketball note elite players. Long a multi functional thorn in the side of things relating to going to be the NCAA, Vaccaro do not forget that is the fact happy to learn more about give you going to be the reminder since a portion of the have claimed that a resource box was going to be the culture overall the amateur artists buy they created that was in part for more information about blame as well as for Team USA?¡¥s drop-off upon a history of a very long time. ?¡ãLook along the players everywhere in the this team!?¡À says Vaccaro. ?¡ãYou can tend to be down going to be the list. The NCAA may say all your family members that the answer to the problem is always that for players to don't hurry a good deal more a period playing and for a multi functional college but take heart most of these great players spent ach and every little time throughout the university.?¡À World championship MVP Kevin Durant took the road that has already been called broken ?¡ãKevin is most likely the youngest relating to them all are,nfl jersey supply,?¡À says Vaccaro. -

Arizona Diamondbacks 2016 Spring Training Game Notes

ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS 2016 SPRING TRAINING GAME NOTES dbacks.com losdbacks.com @Dbacks @LosDbacks facebook.com/D-backs Salt River Fields at Talking Stick 7555 N. Pima Road, Scottsdale, Ariz., 85258 ARIZONA WILDCATS (4-3) AT ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS (0-0) PRESS.DBACKSMEDIA.COM Tuesday, March 1, 2016 ♦ Salt River Fields at Talking Stick ♦ Scottsdale, Ariz. ♦ 3:10 p.m. ♦Daily content includes media guides, game notes, statistical reports, - COLLEGIATE BASEBALL SERIES - lineups, press releases, etc.…please contact a D-backs’ Communica- RHP Michael Flynn (0-0, 21.60) vs. RHP Matt Koch (NR) tions staff member for the login/password. dbacks.com 2016 D-BACKS SPRING SCHEDULE (0-0) DIAMOND-FACTS ROSTER ROUNDUP WINNING LOSING DATE OPP RESULT REC. PITCHER PITCHER ATT. Arizona begins its 19th Cactus League season and sixth ♦ ♦Arizona opens Cactus League play with 68 players in 3/1 UofA 3:10 p.m dbacks.com at Salt River Fields at Talking Stick…Tucson was the Major League camp: 39 pitchers (10 left-handed), 7 3/2 @ COL 1:10 p.m. ESPN Radio 620 club’s spring headquarters from 1998-2010. catchers, 11 infi elders and 11 outfi elders. 3/3 COL 1:10 p.m. ♦D-backs are 301-280-19 all-time during Spring Train- ♦The D-backs return 22 players from its 40-man roster at 3/4 OAK (ss) 1:10 p.m. ing…in 2015, the D-backs went 19-14-2. the start of last Spring Training…Arizona returned 23 3/5 @ LAD 1:05 p.m. Arizona Sports 98.7 FM ♦Arizona’s 19 wins tied for the most in the NL, with New players in 2015 and 26 in 2014. -

Confessions of an Agent This Man Says He Paid Thousands of Dollars to Dozens of College Football Players

This man says he paid thousands of - 10.18.10 - SI Vault Page 1 of 10 Powered by October 18, 2010 Confessions Of An Agent This man says he paid thousands of dollars to dozens of college football players. Whatever they needed—a concert ticket, a free trip, a meal—he gave them, all in violation of NCAA rules. Now he says he wants to come clean about his two decades inside the dirtiest business in sports Josh Luchs, As told to George Dohrmann This story includes the names of 30 former college football players who are alleged to have taken money or some other extra benefit in violation of NCAA rules. The primary source of these allegations is Josh Luchs, who has been a certified NFL agent for 20 years. SI senior writer George Dohrmann met Luchs [pronounced LUX] in July while working on a story about the agent business. Luchs represented more than 60 players during his career, which placed him in the middle class of the industry. He was viewed by other agents as a particularly dogged recruiter and noted for his partnerships with more seasoned player representatives. When Dohrmann learned that Luchs was leaving the profession, he proposed a first-person account of life as an agent. Luchs was initially reluctant but ultimately decided to tell his story. At no point was he promised or given any form of compensation for his participation. In more than 20 hours of interviews Luchs described the payments he says he made to players as well as other events in his career. -

John W. Shrader

JOHN W. SHRADER 2107 Stone Creek Loop S Lincoln, NE 68512 408.910.4510 [email protected] Current Position Associate Professor, Broadcasting and Sports Media Coordinator, Sports Media and Communication College of Journalism and Mass Communications University of Nebraska-Lincoln Specialties and Research Areas of Interest Broadcast Journalism, Sports Broadcasting, Sports Journalism, Writing and Reporting, Social Media, Sport in American Culture, Sport and the Immigrant Experience, Presentation and Representation in the Media, Ethics Education M.S., Mass Communications San Jose State University B.A., Broadcast Journalism University of Nebraska – Lincoln Teaching Experience Associate Professor, Broadcasting and Sports Media University of Nebraska-Lincoln (2017-present) (Teaching Sports Writing, Sports Broadcasting, Introduction to Sports Media, Sport and American Culture, News and Broadcast Capstone) Assistant Professor, Journalism and Broadcasting California State University, Long Beach (2011-2017) promoted to Associate before leaving (Taught Television News, Sports Writing, News Writing, Investigative Reporting, Media and Society, Advisor for KBeach Radio) Lecturer / Adjunct (2007-2011) San Jose State University, Menlo College, San Francisco State University, San Jose City College (Taught Media and Society, Beginning News Writing, Sports Reporting, Television News) Awards and Honors Best of Competition, Sports Radio BEA 2019 “Sport and the Immigrant Experience in Small Town Nebraska” First Place, Outstanding Graduate Research San Jose