Arc Ensemble Music, Conscience and Accountability During the Third Reich

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Survivor from Warsaw' Op. 46

„We should never forget this.“ Holocausterinnerungen am Beispiel von Arnold Schönbergs ‚A Survivor from Warsaw’ op. 46 im zeitgeschichtlichen Kontext. Karolin Schmitt A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of a Master of Arts in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2011 Approved by Prof. Severine Neff, Chair Prof. Annegret Fauser Prof. Konrad H. Jarausch © 2011 Karolin Schmitt ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT KAROLIN SCHMITT: „We should never forget this.“ Holocausterinnerungen am Beispiel von Arnold Schönbergs ‚A Survivor from Warsaw’ op. 46 im zeitgeschichtlichen Kontext. Die vorliegende Masterarbeit interpretiert das Werk ‚A Survivor from Warsaw‘ von Arnold Schönberg auf der Grundlage der von dem Historiker Konrad H. Jarausch beschriebenen Holocaust-Erinnerungskategorien „Survival Stories“, „Figures of Remembrance“ und „Public Memory Culture“. Eine Analyse des Librettos zeigt, dass dieses Werk einzelne „Survival Stories“ künstlerisch zu einer „Figure of Remembrance“ transformiert und beleuchtet die musikalische und kulturelle Aussage dieser trilingualen Textvertonung im Hinblick auf den Ausdruck von kultureller Identität. In meiner Betrachtung des Beitrages dieses Werkes zu einer „Public Memory Culture“ steht vor allem die Kulturpolitik der Siegermächte in beiden Teilen Deutschlands im Mittelpunkt, welche Aufführungen dieses Werkes im Rahmen von Umerziehungsmaßnahmen initiierten und somit ihre eigenen ideologischen Konzepte im öffentlichen Bewusstsein zu stärken versuchten. Dabei werden bislang unberücksichtigte Quellen herangezogen. Eine Betrachtung der Rezeption von ‚A Survivor from Warsaw’ im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert zeigt außerdem die Position dieses Werkes innerhalb eines kontinuierlichen Erinnerungsprozesses, welcher bestrebt ist, reflektiertes Handeln zu fördern. iii This thesis interprets Arnold Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw, op. -

Dante Anzolini

Music at MIT Oral History Project Dante Anzolini Interviewed by Forrest Larson March 28, 2005 Interview no. 1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library Transcribed by: Mediascribe, Clifton Park, NY. From the audio recording. Transcript Proof Reader: Lois Beattie, Jennifer Peterson Transcript Editor: Forrest Larson ©2011 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lewis Music Library, Cambridge, MA ii Table of Contents 1. Family background (00:25—CD1 00:25) ......................................................................1 Berisso, Argentina—on languages and dialects—paternal grandfather’s passion for music— early aptitude for piano—music and soccer—on learning Italian and Chilean music 2. Early musical experiences and training (19:26—CD1 19:26) ............................................. 7 Argentina’s National Radio—self-guided study in contemporary music—decision to become a conductor—piano lessons in Berisso—Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music in La Plata, Argentina—Martha Argerich—María Rosa Oubiña “Cucucha” Castro—Nikita Magaloff— Carmen Scalcione—Gerardo Gandini 3. Interest in contemporary music (38:42—CD2 00:00) .................................................14 Enrique Girardi—Pierre Boulez—Anton Webern—Charles Ives—Carl Ruggles’ Men and Mountains—Joseph Machlis—piano training at Gilardo Gilardi Conservatory of Music—private conductor training with Mariano Drago Sijanec—Hermann Scherchen—Carlos Kleiber— importance of gesture in conducting—São Paolo municipal library 4. Undergraduate education (1:05:34–CD2 26:55) -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief Der Gesellschaft Für Exilforschung E. V

Neuer Nachrichtenbrief der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e. V. Nr. 56 ISSN 0946-1957 Dezember 2020 Inhalt In eigener Sache In eigener Sache 1 Jahrestagung 2020 1 Not macht erfinderisch, und die Corona- Protokoll Mitgliederversammlung 5 Not, die es unmöglich machte, sich wie AG Frauen im Exil 8 gewohnt zur Jahrestagung zu treffen, Call for Papers 2021 9 machte die Organisatorinnen so Exposé 2022 11 erfinderisch, dass sie eine eindrucksvolle Nachruf Ruth Klüger 13 Online-Tagung auf die Beine stellten, der Nachruf Lieselotte Maas 14 nichts fehlte – außer eben dem persönlichen Ausstellung Erika Mann 15 Austausch in den Pausen und beim Projekt Ilse Losa 17 Rahmenprogramm. So haben wir gemerkt, Neuerscheinungen 18 dass man virtuell wissenschaftliche Urban Exile 27 Ergebnisse präsentieren und diskutieren Ausstellung Max Halberstadt 29 kann, dass aber der private Dialog zwischen Suchanzeigen 30 den Teilnehmenden auch eine wichtige Leserbriefe 30 Funktion hat, die online schwer zu Impressum 30 realisieren ist. Wir hoffen also im nächsten Jahr wieder auf eine „Präsenz-Tagung“! Katja B. Zaich Aus der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung Fährten. Mensch-Tier-Verhältnisse in Reflexionen des Exils Virtuelle Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V. in Zusammenarbeit mit der Österreichischen Exilbibliothek im Literaturhaus Wien und der Gesellschaft der Freunde der Österreichischen Exilbibliothek vom 22. bis 24. Oktober 2020 Die interdisziplinäre Jahrestagung der Gesellschaft für Exilforschung e.V. fand 2020 unter den besonderen Umständen der Corona-Pandemie statt. Wenngleich die persönliche Begegnung fehlte, ist es den Veranstalterinnen gelungen, einen regen wissenschaftlichen Austausch im virtuellen Raum zu ermöglichen. Durch die Vielfalt medialer Präsentationsformen wurden die Möglichkeiten digitaler Wissenschaftskommunikation für alle Anwesenden erfahrbar. -

Rathaus, Tiessen & Arma Sonatas for Violin and Piano

RATHAUS, TIESSEN & ARMA SONATAS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO JUDITH INGOLFSSON, VIOLIN | VLADIMIR STOUPEL, PIANO RATHAUS, TIESSEN & ARMA SONATAS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO KAROL RATHAUS (1895–1954) SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, OP. 14 (1925) [01] I. Andantino ......................................09:40 [02] II. Intermezzo. Andante ............................. 06:13 [03] III. Rondo. Allegro ma non troppo ..................... 08:41 HEINZ TIESSEN (1887–1971) DUO-SONATA, OP. 35 (1925)* [04] I. Präludium. Allegro non troppo ...................... 01:48 [05] II. Andante quasi adagio .............................06:16 [06] III. Finale. Allegro molto vivace .......................07:48 2 RATHAUS, TIESSEN & ARMA SONATAS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO PAUL ARMA (1905–1987) SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO (1949)* [07] I. Lento .......................................... 15:59 [08] II. Interlude. Sostenuto rubato ........................03:02 [09] III. Allegro .......................................08:36 [10] IV. Postlude. Sostenuto rubato ........................ 02:55 * WORLD PREMIERE RECORDING JUDITH INGOLFSSON, VIOLIN VLADIMIR STOUPEL, PIANO TOTAL 71:04 3 RATHAUS, TIESSEN & ARMA RATHAUS Es war Schrenk, dem Rathaus seine Sona- te für Violine und Klavier Nr. 1 op. 14 widmete. eboren in Tarnopol (damals Öster- Komponiert 1925, wurde sie gemäß sei- Greich-Ungarn) in einer polnisch-jüdi- nem Verlagsvertrag von der Universal Edition schen Familie, begann Karol Rathaus schon veröffentlicht. Die Uraufführung der Sonate früh zu komponieren. An der Akademie für fand im März 1926 in Berlin mit dem Kompo- Darstellende Kunst und Musik Wien nahm nisten am Klavier und seinem Freund Stefan er 1913 sein Studium auf, das jäh durch den Frenkel an der Violine statt. In diesem farben- Ersten Weltkrieg unterbrochen wurde: Vier freudigen und phantasievollen Stück kombi- Jahre lang musste er in der österreichischen niert Rathaus die Innigkeit der Kammermusik Armee dienen. -

TOC 0245 CD Booklet.Indd

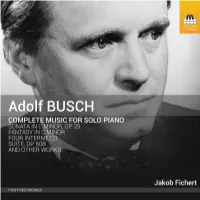

ADOLF BUSCH AND THE PIANO by Jakob Fichert It’s hardly a secret that Adolf Busch (1891–1952) was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century. But only specialists, it seems, are aware that he was also a very fne composer, even though these two artistic identities – performer and composer – were of equal importance to him. In recent years some of his chamber works, his organ music and parts of his symphonic œuvre have been recorded, allowing some appreciation of his stature as a creative fgure. But Busch’s music for solo piano has yet to be discovered – only the Andante espressivo, BoO1 37 22 , has been recorded before now, by Peter Serkin, Busch’s grandson, and that in a private recording, not available commercially. Tis album therefore presents the entirety of Busch’s piano output for the frst time. Busch’s writing for solo piano forms a kind of huge triptych, with the Sonata in C minor, Op. 25, as its central panel; another major work, a Fantasia in C major, BoO 20, was written early in his career; and a later Suite, Op. 60b, dates from the time of his full maturity. Busch also wrote more than a dozen smaller piano pieces, in which he seems to have experimented with various genres in pursuit of the development of his musical language, with four Intermezzi, a Scherzo and other character pieces among them. One can hear the infuence of Brahms, Mendelssohn, Busoni and – especially – Reger, but with familiarity Busch’s style can be heard to be distinctive and personal, displaying a unique and highly expressive world of sound. -

Radical Than Most Gebrauchsjazz: Music for the “Berlin Im Licht”

More Radical Than Most Gebrauchsjazz. Music for the "Berlin im Licht" Festival by Nils Grosch 'The harmonies and melodies are more radical than with their "Berlin im Licht" pieces. On 8July 1928 Butting reported most Gebrauchsjazz" concluded Erwin Stein in his 1928 report to UE, ''I will speak with Weill and Tiessen about the festival to Universal Edition, Vienna (UE) when asked to evaluate the during the next few days." Six weeks later, on 18 August, music composed by Max Butting and Heinz Tiessen for the Butting submitted his two compositions (a "Blues" and a "Berlin im Licht'' festival. Butting and Tiessen, along with Kurt "Marsch") along with a "Foxtrott" and a "Boston" byTiessen. Weill, Wladimir Vogel, Stefan Wolpe, Hanns Eisler, and Philipp Weill's song was to follow in a few days.4 Jarnach , were counted among the leaders of the music section Butting made clear his intentions for the festival in a polemi of the Novembergruppe and considered representatives of cal announcement intended for publication in UE'sMusikblatter Berlin's musical avant-garde. des Anbruch. The open-air concerts were to be an affront to the Some months earlier, Max Butting had explained his ideas devotional behavior of bourgeois German concert-goers as for the "Berlin im Licht" festival in a letter dated 2July 1928 to well as a reaction to the snootiness of many of his colleagues. UE: "Naturally, only popular events "We Germans are a strange people. are planned, featuring about six simul We have an indestructible respect for taneous open-air concerts (Stand things thatwe can scarcely understand musiken). -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Adolf Busch: the Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online

yiMmZ (Ebook pdf) Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online [yiMmZ.ebook] Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Pdf Free Tully Potter DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3756817 in Books Toccata Press 2010-09-17Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 3.97 x 7.32 x 9.02l, 7.55 #File Name: 09076895071408 pagesthe life and times of Adolf Busch, the "honest musician" | File size: 43.Mb Tully Potter : Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set): 9 of 10 people found the following review helpful. An Exemplary Life and Musical History of the TimesBy Edgar SelfLong awaited, this biography of violinist, composer, quartet and trio leader, teacher, and conductor Adolf Busch (1891-1952), co-founder of the Marlboro School of Music, is a history of the violin, of concerts and chamber-music in the first half of the 20th century. The texts, research notes, copious illustrations, and appendices detail virtually every concert and associate of Busch's life with full descriptions of his musical and personal relations with Reger, Busoni, Tovey, Roentgens and hundreds of others, including those unsympathetic to him such as Furtwaengler, Sibelius, Edwin Fischer, and Elly Ney, for musical or political reasons. Busch's early immigration from Germany and his part in creating the Lucerne Festival and Palestine Symphony Orchestra, precursor of the Israel Philharmonic, before settling in the U.S. -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

Eine Dadaistisch-Futuristische Provokation

KLAVIERMUSIK DER BERLINER NOVEMBERGRUPPE: eine dadaistisch-futuristische Provokation Heinz Tiessen GESPRÄCHSKONZERT DER REIHE MUSICA REANIMATA AM 16. MAI 2013 IN BERLIN BESTANDSVERZEICHNIS DER MEDIEN ZUM GLEICHNAMIGEN THEMA IN DER ZENTRAL- UND LANDESBIBLIOTHEK BERLIN LEBENSDATEN Max Butting 1888 - 1976 Hanns Eisler 1898 - 1962 Eduard Erdmann 1896 - 1958 Philipp Jarnach 1892 - 1982 Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt 1901 - 1988 Heinz Tiessen 1887 - 1971 Kurt Weill 1900 - 1950 Stefan Wolpe 1902 - 1972 Wladimir Vogel 1896 - 1984 INHALTSANGABE ELEKTRONISCHE RESSOURCEN Seite 3 KOMPOSITIONEN Noten Seite 3 Tonträger Seite 4 SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR Seite 7 LEGENDE Freihand Bestand im Lesesaal frei zugänglich Magazin Bestand für Leser nicht frei zugänglich, Bestellung möglich Außenmagazin Bestand außerhalb der Häuser, Bestellung möglich AGB Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek, Blücherplatz 1, 10961 Berlin – Kreuzberg BStB Berliner Stadtbibliothek, Breite Str. 30-36, 10178 Berlin – Mitte 2 ELEKTRONISCHE RESSOURCEN (AUSZUG) Zuzüglich zu den nachfolgenden Medien können Sie Audiodateien und weitere Quellen zu den genannten Komponisten vor Ort in der Bibliothek über die Lizenzdatenbank Naxos Music Library recherchieren und anhören. Gerne sind Ihnen die Kolleginnen und Kollegen am Musikpult behilflich. Datenbank-PC: Standort Musikabteilung AGB KOMPOSITIONEN NOTEN (Auszug) Erdmann, Eduard: [Stücke, Kl, op. 6] Fünf Klavierstücke : op. 6 ; [Noten] [Noten] / Eduard Erdmann. - Berlin : Ries & Erler, c 1994. - 11 S. - Hinweis auf die musikalische Form und/oder Besetzung: Für Klavier Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 350 Erd E 1 Jarnach, Philipp: [Stücke, Kl, op. 17] Drei Klavierstücke : (1924) ; opus 17 ; [Noten] = Three piano pieces [Noten] / Philipp Jarnach. - New ed. - Mainz [u.a.] : Schott, c 1999. - 23 S. ; 30 cm. – Exemplare: Standort Magazin AGB Signatur No 350 Jar 1 Stuckenschmidt, Hans Heinz: [Neue Musik] Neue Musik : drei Klavierstücke ; (1919 - 1921) [Noten] / Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt. -

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Beethoven Volume 4 Country: UK Released: 2009 Style: Classical MP3 version RAR size: 1345 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1648 mb WMA version RAR size: 1589 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 721 Other Formats: TTA XM DMF AHX AU AUD APE Tracklist Quartet No.13 In B Flat Op.130 1 I: Adagio Ma non Troppo 8:56 2 II: Presto 1:54 3 III: Andante Con Moto, Ma Non Troppo 5:23 4 IV: Alla Danza Tedesca: Allegro Assai 2:23 5 V. Cavatina: Adagio Molto Espressivo 7:00 6 VI. Finale: Allegro 8:27 Quartet No.15 In A Minor Op.132 7 I: Assai Sostenuto - Allegro 4:03 8 II: Allegro Ma Non Tanto 6:15 III: Heilger Dankesang Eines Genesenen An Die Gottheit, In Der 9 3:45 Lydischen Tonart: Molto Adagio - Andante - Mit Innigster EmpFundung 10 IV: Alla Marcia, Assai Vivace 4:26 11 V. Allegro Appassionato Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dutton Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Credits Cello – Herman Busch* Composed By – Ludwig van Beethoven Ensemble – The Busch Quartet Liner Notes – Tully Potter Remastered By – Michael Dutton* Viola – Karl Doktor Violin – Adolph Busch, Gösta Andreasson (tracks: Gösta Andreassen) Notes Tracks 1 to 6: Recorded at Liederkranz Hall, NY 13 & 16 June 1941 Tracks 7 to 11: Recorded at Abbey Road Studio no. 3, on 7 October 1937 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 65387 97942 3 Rights Society: MCPS SPARS Code: ADD Matrix / Runout: [Manufactured by kdg] 672.658 CDBP 9794 Mould SID Code: IFPI 3066 Related Music albums to Beethoven Volume 4 by The Busch Quartet Mendelssohn – Pacifica Quartet - The Complete String Quartets Beethoven - Alban Berg Quartett - Complete String Quartets Artur Schnabel, Ludwig van Beethoven - Beethoven the Complete Piano Sonatas on Thirteen Discs Beethoven, Paul Lewis - Complete Piano Sonatas John Lill - Beethoven Piano Sonatas Complete Vol I Beethoven, Juilliard String Quartet - Quartet In A Minor Op.