Biodiversity Audit and Objective Setting Exercise for the Green Arc Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Environment Characterisation Project

HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Chelmsford Borough Historic Environment Characterisation Project abc Front Cover: Aerial View of the historic settlement of Pleshey ii Contents FIGURES...................................................................................................................................................................... X ABBREVIATIONS ....................................................................................................................................................XII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................... XIII 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSE OF THE PROJECT ............................................................................................................................ 2 2 THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF CHELMSFORD DISTRICT .................................................................................. 4 2.1 PALAEOLITHIC THROUGH TO THE MESOLITHIC PERIOD ............................................................................... 4 2.2 NEOLITHIC................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.3 BRONZE AGE ............................................................................................................................................... 5 -

London LOOP Section 22 Harold Wood to Upminster Bridge

V4 : May 2011V4 : May London LOOP Directions: Exit Harold Wood station by the stairs at the end of the platform Section 22 to join the LOOP route which passes the station‟s main exit. Harold Wood to Upminster Bridge Once outside the station and on Gubbins Lane turn left then left again into Oak Road. Follow the road straight ahead past Athelstan Road and Ethelburga Road – lots of Saxon names here - and then go down Archibald Road, the third street on the right. Go through the metal barrier onto the gravel road passing the houses on the right and the Ingrebourne River quietly flowing by on the left. Continue on the short stretch of tarmac road to the busier Squirrels Heath Road and turn right. Start: Harold Wood (TQ547905) Station: Harold Wood After a short distance turn left into the modest Brinsmead Road A which Finish: Upminster Bridge (TQ550868) leads to Harold Wood Park. Station: Upminster Bridge Go through the gate and turn immediately right onto the path. Just before Distance: 4 miles (6.9 km) the carpark turn left to follow the tarmac path along the avenue of trees, passing tennis courts on the right. At the end of the path turn left and go past the children‟s playground on the right. A footbridge comes into view on Introduction: This section goes through Pages Wood - a superb new the right. Go over the Ingrebourne River via the wooden footbridge to enter community woodland of 74 hectares, as well as other mysterious woodland, Pages Wood. Turn right and follow the gravel path. -

Archive Page

Archive Page Sightings and news from July to December 2006 Archive Index Photo House Index This page contains sightings details of all the butterflies and moths reported to the Sightings page between July and December 2006. Note: These pages have been copied from the original sightings page and some links will no longer work. All images of butterflies or moths have been removed, but most can be found in the Photo House December 2006 Thursday 28th December When you think it is all over for sightings of butterflies this year, it isn't! On the way to Kew Gardens for the ice skating today the 28th December on the Chiswick roundabout, I spotted a Red Admiral flying past. Then while waiting for the children to get their boots on at the ice rink another Red Admiral flew past, probably disturbed from it's hibernation from the massive influx of people, or the fact it was a very warm day for this time of year? If this is the result of global warming, well it's not all bad!! Helen George My father told me that he saw a butterfly in Bronte Paths, Stevenage this morning. I assume it was a Red Admiral (just hope it wasnt a wind blown leaf!. It was very warm today, with lots of insects and one or two bees in my garden but despite all my attention no butterflies appeared - Phil Bishop Tuesday 26th December I enjoyed today even more with a totally unexpected Red Admiral flying along the eaves of my house and then the neighbours, at about 10.45 this am - weather was grey, dull and 5C. -

Rye Meads Water Cycle Study\F-Reports\Phase 3\5003-Bm01390-Bmr-18 Water Cycle Strategy Final Report.Doc

STEVENAGE BOROUGH COUNCIL RYE MEADS WATER CYCLE STRATEGY DETAILED STUDY REPORT FINAL REPORT Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited 2212959 Aston Cross Business Village 50Rocky Lane Aston Birmingham B6 5RQ United Kingdom Tel: +44 (0)870 000 3007 Fax: +44 (0)870 000 3907 www.hyderconsulting.com STEVENAGE BOROUGH COUNCIL RYE MEADS WATER CYCLE STRATEGY DETAILED STUDY REPORT FINAL REPORT James Latham/ Dan Author Vogtlin Checker Renuka Gunasekara Approver Mike Irwin Report No 5003-BM01390-BMR-18-Water Cycle Strategy Final Report Date 5th October 2009 This report has been prepared for STEVENAGE BOROUGH COUNCIL in accordance with the terms and conditions of appointment for WATER CYCLE STRATEGY dated April 2008. Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited (2212959) cannot accept any responsibility for any use of or reliance on the contents of this report by any third party. RYE MEADS WATER CYCLE STRATEGY—DETAILED STUDY REPORT Hyder Consulting (UK) Limited-2212959 k:\bm01390- rye meads water cycle study\f-reports\phase 3\5003-bm01390-bmr-18 water cycle strategy final report.doc Revisions Prepared Approved Revision Date Description By By - 2/10/2008 Draft Report Structure JL 1 18/11/2008 First Report Draft JL/DV MI 2 27/01/2009 Draft Report JL/DV MI 3-13 03/04/2009 Final Draft Report as amended by stakeholder comments JL/DV RG 14 09/07/2009 Final Draft Report JL/DV RG 15 10/07/2009 Final Draft Report Redacted JL/DV RG 16 21/08/2009 Final Draft Report JL/DV RG 17 21/09/2009 Final Draft following core project team meeting comments JL/DV RG 18 05/10/2009 Final Report JL/DV MI RYE MEADS WATER CYCLE STRATEGY—DETAILED STUDY REPORT Hyder Consulting (UK) Ltd-2212959 k:\bm01390- rye meads water cycle study\f-reports\phase 3\5003-bm01390-bmr-18 water cycle strategy final report.doc CONTENTS 1 Introduction and Summary of Key Outcomes .................................... -

Report on Rare Birds in Great Britain in 1996 M

British Birds Established 1907; incorporating 'The Zoologist', established 1843 Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 1996 M. J. Rogers and the Rarities Committee with comments by K. D. Shaw and G. Walbridge A feature of the year was the invasion of Arctic Redpolls Carduelis homemanni and the associated mass of submitted material. Before circulations began, we feared the worst: a huge volume of contradictory reports with differing dates, places and numbers and probably a wide range of criteria used to identify the species. In the event, such fears were mostly unfounded. Several submissions were models of clarity and co-operation; we should like to thank those who got together to sort out often-confusing local situations and presented us with excellent files. Despite the numbers, we did not resort to nodding reports through: assessment remained strict, but the standard of description and observation was generally high (indeed, we were able to enjoy some of the best submissions ever). Even some rejections were 'near misses', usually through no fault of the observers. Occasionally, one or two suffered from inadequate documentation ('Looked just like bird A' not being quite good enough on its own). Having said that, we feel strongly that the figures presented in this report are minimal and a good many less-obvious individuals were probably passed over as 'Mealies' C. flammea flammea, often when people understandably felt more inclined to study the most distinctive Arctics. The general standard of submissions varies greatly. We strongly encourage individuality, but the use of at least the front of the standard record form helps. -

Essex Bat Group Newsletter 2015 Spring

Spring Newsletter2015 A Bat In The Box... Andrew Palmer on the beginning of an important new bat box monitoring project It has been known for a fair while that Nathusius' pipistrelle are regularly encountered foraging in in the Lee Valley Regional Park just north and south of the M25 in an area dominated by major reservoirs and old flooded gravel workings. These significant water bodies combined with a mosaic of river courses, flood relief channels, permanent conservation grasslands, riparian trees, wet woodland and housing estates of various ages make for pip nirvana. Add in to the mix a large area of nearby woodland (Epping Forest) and the Thames estuary migration corridor and it is no wonder a small bats’ head might be turned. With records of rescued Nathusius' including a juvenile from the area and advertising males nearby, a search of the area was bound to produce more detections. In April 2014 a walk along the flood relief channel near Sewardstone produced an abundance of Nathusius' activity. As a consequence and with the help of Daniel Hargreaves the bat group arranged trapping nights in Gunpowder Park and at Fishers Green in August and September and caught Nathusius' pips on both nights (5 males). With a very positive and well established relationship with the site owners, the Lee Valley Regional Park Authority, we asked if it would be possible to establish a bat box monitoring project, as part of the Essex Nathusius’ Pipistrelle Project, along the lines of that run by Patty Briggs at Bedfont Lakes, west London. Patty regularly finds good numbers of Nathusius' pips in the bat boxes set in wet woodland. -

Winchmore Hill

Enfield Society News No. 194, Summer 2014 Enfield’s ‘mini-Holland’ project: for and against In our last issue we discussed some of the proposals in Enfield Council’s bid under the London Mayor’s “mini-Holland” scheme to make the borough more cycle-friendly. On 10th March the Mayor announced that Enfield was one of three boroughs whose bids had been selected and that we would receive up to £30 million to implement the project. This provides a great opportunity to make extensive changes and improvements which will affect everyone who uses our streets and town centres, but there is not unanimous agreement that the present proposals are the best way of spending this money. The Council has promised extensive consultations before the proposals are developed to a detailed design stage, but it is not clear whether there are conditions attached to the funds which would prevent significant departures from the proposals in the bid. The Enfield Society thinks that it would be premature to express a definitive view until the options have been fully explored, but we are keen to participate in the consultation process, in accordance with the aim in our constitution to “ensure that new developments are environmentally sound, well designed and take account of the relevant interests of all sections of the community”. We have therefore asked two of our members to write columns for and against the current proposals, in order to stimulate discussion. A third column, from the Enfield Town Conservation Area Study Group, suggests a more visionary transformation of Enfield Town. Yes to mini-Holland! Doubts about mini- Let’s start with the people of Enfield. -

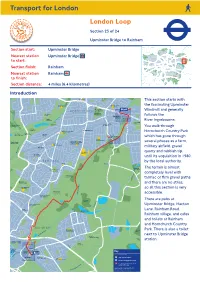

London Loop. Section 23 of 24

Transport for London. London Loop. Section 23 of 24. Upminster Bridge to Rainham. Section start: Upminster Bridge. Nearest station Upminster Bridge . to start: Section finish: Rainham. Nearest station Rainham . to finish: Section distance: 4 miles (6.4 kilometres). Introduction. This section starts with the fascinating Upminster Windmill and generally follows the River Ingrebourne. You walk through Hornchurch Country Park which has gone through several phases as a farm, military airfield, gravel quarry and rubbish tip, until its acquisition in 1980 by the local authority. The terrain is almost completely level with tarmac or firm gravel paths and there are no stiles, so all this section is very accessible. There are pubs at Upminster Bridge, Hacton Lane, Rainham Road, Rainham village, and cafes and toilets at Rainham and Hornchurch Country Park. There is also a toilet next to Upminster Bridge station. Directions. Leave Upminster Bridge station and turn right onto the busy Upminster Road. Go under the railway bridge and past The Windmill pub on the left. Cross lngrebourne River and then turn right into Bridge Avenue. To visit the Upminster Windmill continue along the main road for a short distance. The windmill is on the left. Did you know? Upminster Windmill was built in 1803 by a local farmer and continued to grind wheat and produce flour until 1934. The mill is only open on occasional weekends in spring and summer for guided tours, and funds are currently being raised to restore the mill to working order. Continue along Bridge Avenue to Brookdale Avenue on the left and opposite is Hornchurch Stadium. -

Unacceptable Housing Target Challenged

MARCH 2018 Harold Wood, Hill, Park Residents’ Association THE BULLETIN The Voice of the Community email: [email protected] Delivered by the Residents’ Association www.hwhpra.org.uk Additional Police Unacceptable Housing Officer For Harold Target Challenged Wood Ward We were delighted to meet our new As reported in the January Bulletin, the Mayor of London is proposing that experienced Police Officer Richard Havering build 18,750 (1,875 pa) households over the decade, a 60% increase Clay for the local neighbourhood on the 11,750 (1,175 pa) target already proposed by the Council. We recently team at one of their open meetings debated a motion opposing this target in the Council Chamber and it was agreed recently. Richard will be with the to submit the strongest possible response to the Mayor of London challenging team for about 2 years and we are this unacceptable, unsustainable and unachievable target. We also argued glad that he has joined the team. The that more should be done about the 20,000 households that have been lying petition that residents signed helped empty for two years or more in London and more freedoms given to councils to bring this about as the petition was to replenish Council housing stock sold through Right to Buy. We all need presented to the Mayor Of London. somewhere to live that is sustainable, has character, where we can breathe clean air and somewhere where we are proud to call home. But cramming more and Cllr DARREN WISE, Cllr BRIAN more people into less and less space is just a recipe for disharmony, discontent EAGLING, Martin Goode and choking congestion. -

The Hundred Parishes HUNSDON

The Hundred Parishes An introduction to HUNSDON 4 miles NW of Harlow. Ordnance Survey grid square TL4114. Postcode SG12 8NJ. Access: B180, no train station. The village is served by bus routes 351 (Hertford to Bishop‘s Stortford), C3 (Waltham Cross to Hertford or Harlow) and 5 (South End to Harlow Sats. only). County: Hertfordshire. District: East Hertfordshire. Population: 1,080 in 2011. The village of Hunsdon was registered in the Domesday Book of 1086. The village centre is dominated by the 15th-century village hall, originally a house called ’The Harlowes’ which had previously been the village school as far back as at least 1806. The hall faces one of the village’s original 5 greens, mainly now used as a pub car park but also the site of the war memorial. A number of houses in the village date back to the same period as the hall, including ’White Horses’ to the right of the village hall, while many others are of subsequent centuries. Hunsdon’s greatest claim to fame is as the site of Hunsdon House to the east of the church. The house was built in the 15th century by Sir William Oldhall, but by the 16th century the building and its extensive parks were in the hands of the Crown. Henry VIII rebuilt the house expanding it into a palatial estate in the Tudor style, complete with royal apartments and even a moat, making it into a splendid palace. Henry spent much of his leisure time at Hunsdon hunting in the well stocked deerpark. All of the King’s children lived there, Mary until her accession to the throne, Elizabeth and particularly Prince Edward. -

The Essex County Council (Hatfield Forest Road) (Temporary Stopping Restriction) Order 2020

The Essex County Council (Hatfield Forest Road) (Temporary Stopping Restriction) Order 2020 Notice is hereby given Colchester Borough Council acting on behalf of the North Essex Parking Partnership in exercise of the delegated powers of the traffic authority Essex County Council granted under an Agreement dated 31 March 2011 proposes to make a temporary Order under Sections 14(1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 The effect of the Order: To temporarily replace current double yellow lines (No Waiting At Any Time) with double red lines (No Stopping At Any Time) on the entire lengths of Hatfield Forest Road and Bush End Road, and on each side of the junction with Hatfield Forest Road on The Street (B1256) in the district of Uttlesford. Nothing in the Order shall apply to anything done with the permission or at the direction of a police constable in uniform or a Civil Enforcement Officer. Nothing in the Order shall apply to any emergency vehicles. The Order is proposed come into operation on 29 June 2020 to remain in force for a period of up to 18 months. Date: 18 June 2020 Richard Walker, Parking Partnership Group Manager, Colchester Borough Council, Rowan House, 33 Sheepen Road, Colchester, CO3 3WG Tile Reference: TL545 210 SEE STATIC MAP SCHEDULE LEGEND FOR RESTRICTIONS DIS PROPOSED HHiiiiililllllllllcccrrrrooofffffttttt TTiiiiiimmbbbeeerrrr HHooouuussseee WWoooooodddsssiiiiididdeee CCoootttttttttaaagggeee DDrrrraaakkkeeelllllalaannndddsss P a t h ( u m SStttttaaannnhhhooollllllmm ) TThhheee BBuuunnngggaaalllllloooww WWoooooodddbbbrrrriiiiiaiaarrrr -

Essex Moth Group Newsletter 42 Autumn 2008 AGM Saturday March 21St 2009

Essex Moth Group Newsletter 42 Autumn 2008 AGM Saturday March 21st 2009 The ANNUAL MEETING AND EXHIBITION will once again be at the Venture Centre in Lawford on SATURDAY MARCH 21st 2009 (10:30 - 5:30). The main parts of this newsletter can be found on www.essexfieldclub.org.uk Go to groups in the middle of the first page and choose moths or type http://www.essexfieldclub.org.uk/portal/p/Moths HIGHLIGHTS of 2008 BEAUTIFUL SNOUT Colchester (David Barnard) - FIRST FOR ESSEX The weather looked fine on the evening of Tuesday 15 July 2008, so I decided that it would be a good opportunity to run my moth trap after a long spell of indifferent weather. My trap is a Skinner type operating with a 15w actinic tube and located on the lawn of my average sized suburban garden. The lamp was switched on at 9.30pm and operated until 1.30am on Wednesday 16th with visual inspection until 11.00pm. Garden location is Alresford, near Colchester. An early morning inspection on 16 July revealed 11 species of macro moths plus several species of micros – a typical ‘catch’ for my location. However, one moth was not immediately identified and this was potted for checking. My first thoughts were that it was one of the larger pyralids but when I checked British Pyralid Moths (Goater) I still could not identify it. I then checked with the Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland (Townsend & Waring) and identified it as a fairly worn specimen of a female Beautiful Snout Hypena crassalis (Bradley 2476).