Tickborne Diseases of the United States: a Reference Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

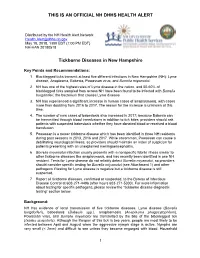

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Vector Hazard Report: Ticks of the Continental United States

Vector Hazard Report: Ticks of the Continental United States Notes, photos and habitat suitability models gathered from The Armed Forces Pest Management Board, VectorMap and The Walter Reed Biosystematics Unit VectorMap Armed Forces Pest Management Board Table of Contents 1. Background 4. Host Densities • Tick-borne diseases - Human Density • Climate of CONUS -Agriculture • Monthly Climate Maps • Tick-borne Disease Prevalence maps 5. References 2. Notes on Medically Important Ticks • Ixodes scapularis • Amblyomma americanum • Dermacentor variabilis • Amblyomma maculatum • Dermacentor andersoni • Ixodes pacificus 3. Habitat Suitability Models: Tick Vectors • Ixodes scapularis • Amblyomma americanum • Ixodes pacificus • Amblyomma maculatum • Dermacentor andersoni • Dermacentor variabilis Background Within the United States there are several tick-borne diseases (TBD) to consider. While most are not fatal, they can be quite debilitating and many have no known treatment or cure. Within the U.S., ticks are most active in the warmer months (April to September) and are most commonly found in forest edges with ample leaf litter, tall grass and shrubs. It is important to check yourself for ticks and tick bites after exposure to such areas. Dogs can also be infected with TBD and may also bring ticks into your home where they may feed on humans and spread disease (CDC, 2014). This report contains a list of common TBD along with background information about the vectors and habitat suitability models displaying predicted geographic distributions. Many tips and other information on preventing TBD are provided by the CDC, AFPMB or USAPHC. Back to Table of Contents Tick-Borne Diseases in the U.S. Lyme Disease Lyme disease is caused by the bacteria Borrelia burgdorferi and the primary vector is Ixodes scapularis or more commonly known as the blacklegged or deer tick. -

Tick-Borne Diseases Primary Tick-Borne Diseases in the Southeastern U.S

Entomology Insect Information Series Providing Leadership in Environmental Entomology Department of Entomology, Soils, and Plant Sciences • 114 Long Hall • Clemson, SC 29634-0315 • Phone: 864-656-3111 email:[email protected] Tick-borne Diseases Primary tick-borne diseases in the southeastern U.S. Affecting Humans in the Southeastern United Disease (causal organism) Tick vector (Scientific name) States Lyme disease Black-legged or “deer” tick (Borrelia burgdorferi species (Ixodes scapularis) Ticks are external parasites that attach themselves complex) to an animal host to take a blood meal at each of Rocky Mountain spotted fever American dog tick their active life stages. Blood feeding by ticks may (Rickettsia rickettsii) (Dermacentor variabilis) lead to the spread of disease. Several common Southern Tick-Associated Rash Lone star tick species of ticks may vector (transmit) disease. Many Illness or STARI (Borrelia (Amblyomma americanum) tick-borne diseases are successfully treated if lonestari (suspected, not symptoms are recognized early. When the disease is confirmed)) Tick-borne Ehrlichiosis not diagnosed during the early stages of infection, HGA-Human granulocytic Black-legged or “deer” tick treatment can be difficult and chronic symptoms anaplasmosis (Anaplasma (Ixodes scapularis) may develop. The most commonly encountered formerly Ehrlichia ticks in the southeastern U.S. are the American dog phagocytophilum) tick, lone star tick, blacklegged or “deer” tick and HME-Human monocytic Lone star tick brown dog tick. While the brown dog tick is notable Ehrlichiosis (Amblyomma americanum) because of large numbers that may be found indoors (Ehrlichia chafeensis ) American dog tick when dogs are present, it only rarely feeds on (Dermacentor variabilis) humans. -

Mitochondrial DNA Sequence Variation in Ixodes Paci®Cus (Acari: Ixodidae)

Heredity 83 (1999) 378±386 Received 20 August 1998, accepted 7 July 1999 Mitochondrial DNA sequence variation in Ixodes paci®cus (Acari: Ixodidae) DOUGLAS E. KAIN*, FELIX A. H. SPERLING , HOWELL V. DALY & ROBERT S. LANE Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, Division of Insect Biology, University of California at Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720, U.S.A. The western black-legged tick, Ixodes paci®cus, is a primary vector of the spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi, that causes Lyme disease. We used variation in a 355-bp DNA portion of the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase III gene to assess the population structure of the tick across its range from British Columbia to southern California and east to Utah. Ixodes paci®cus showed considerable haplotype diversity despite low nucleotide diversity. Maximum parsimony and isolation- by-distance analyses revealed little genetic structure except between a geographically isolated Utah locality and all other localities. Loss of mtDNA polymorphism in Utah ticks is consistent with a post- Pleistocene founder event. The pattern of genetic dierentiation in the continuous part of the range of Ixodes paci®cus reinforces recent recognition of the diculties involved in using genetic frequency data to infer gene ¯ow and migration. Keywords: gene ¯ow, Ixodes paci®cus, Ixodidae, Lyme disease, mitochondrial DNA, population structure. Introduction stages of I. paci®cus each feed once and then drop from the host to moult or lay eggs under leaf litter (Peavey & The western black-legged tick, Ixodes paci®cus, is one of Lane, 1996). Eective gene ¯ow is likely to occur only the most medically important ticks in western North when there is sucient rainfall, ground cover and soil America. -

Ehrlichiosis

Ehrlichiosis What is ehrlichiosis and can also have a wide range of signs Who should I contact, if I what causes it? including loss of appetite, weight suspect ehrlichiosis? Ehrlichiosis (air-lick-ee-OH-sis) is a loss, prolonged fever, weakness, and In Animals – group of similar diseases caused by bleeding disorders. Contact your veterinarian. In Humans – several different bacteria that attack Can I get ehrlichiosis? the body’s white blood cells (cells Contact your physician. Yes. People can become infected involved in the immune system that with ehrlichiosis if they are bitten by How can I protect my animal help protect against disease). The an infected tick (vector). The disease organisms that cause ehrlichiosis are from ehrlichiosis? is not spread by direct contact with found throughout the world and are Ehrlichiosis is best prevented by infected animals. However, animals spread by infected ticks. Symptoms in controlling ticks. Inspect your pet can be carriers of ticks with the animals and humans can range from frequently for the presence of ticks bacteria and bring them into contact mild, flu-like illness (fever, body aches) and remove them promptly if found. with humans. Ehrlichiosis can also to severe, possibly fatal disease. Contact your veterinarian for effective be transmitted through blood tick control products to use on What animals get transfusions, but this is rare. your animal. ehrlichiosis? Disease in humans varies from How can I protect myself Many animals can be affected by mild infection to severe, possibly fatal ehrlichiosis, although the specific infection. Symptoms may include from ehrlichiosis? bacteria involved may vary with the flu-like signs (chills, body aches and The risk for infection is decreased animal species. -

And Toxoplasmosis in Jackass Penguins in South Africa

IMMUNOLOGICAL SURVEY OF BABESIOSIS (BABESIA PEIRCEI) AND TOXOPLASMOSIS IN JACKASS PENGUINS IN SOUTH AFRICA GRACZYK T.K.', B1~OSSY J.].", SA DERS M.L. ', D UBEY J.P.···, PLOS A .. ••• & STOSKOPF M. K .. •••• Sununary : ReSlIlIle: E x-I1V\c n oN l~ lIrIUSATION D'Ar\'"TIGENE DE B ;IB£,'lA PH/Re El EN ELISA ET simoNi,cATIVlTli t'OUR 7 bxo l'l.ASMA GONIJfI DE SI'I-IENICUS was extracted from nucleated erythrocytes Babesia peircei of IJEMIiNSUS EN ArRIQUE D U SUD naturally infected Jackass penguin (Spheniscus demersus) from South Africo (SA). Babesia peircei glycoprotein·enriched fractions Babesia peircei a ele extra it d 'erythrocytes nue/fies p,ovenanl de Sphenicus demersus originoires d 'Afrique du Sud infectes were obto ined by conca navalin A-Sepharose affinity column natulellement. Des fractions de Babesia peircei enrichies en chromatogrophy and separated by sod ium dodecyl sulphate glycoproleines onl ele oblenues par chromatographie sur colonne polyacrylam ide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE ). At least d 'alfinite concona valine A-Sephorose et separees par 14 protein bonds (9, 11, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, electrophorese en gel de polyacrylamide-dodecylsuJfale de sodium 120, 204, and 205 kDa) were observed, with the major protein (SOS'PAGE) Q uotorze bandes proleiques au minimum ont ete at 25 kDa. Blood samples of 191 adult S. demersus were tes ted observees (9, 1 I, 13, 20, 22, 23, 24, 43, 62, 90, 120, 204, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assoy (ELISA) utilizing B. peircei et 205 Wa), 10 proleine ma;eure elant de 25 Wo. -

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Weekly March 20, 2009 / Vol

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report www.cdc.gov/mmwr Weekly March 20, 2009 / Vol. 58 / No. 10 Trends in Tuberculosis — World TB Day — March 24, 2009 United States, 2008 World TB Day is observed each year on March 24 to commemorate the date in 1882 when Dr. Robert Koch In 2008, a total of 12,898 incident tuberculosis (TB) cases announced the discovery of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the were reported in the United States; the TB rate declined 3.8% bacterium that causes tuberculosis (TB). Worldwide, TB from 2007 to 4.2 cases per 100,000 population, the lowest remains one of the leading causes of death from infectious rate recorded since national reporting began in 1953. This disease. An estimated 2 billion persons are infected with report summarizes provisional 2008 data from the National M. tuberculosis (1). In 2006, approximately 9.2 million TB Surveillance System and describes trends since 1993. persons became ill from TB, and 1.7 million died from Despite this overall improvement, progress has slowed in the disease (1). World TB Day provides an opportunity recent years; the average annual percentage decline in the TB for TB programs, nongovernmental organizations, and rate decreased from 7.3% per year during 1993–2000 to 3.8% other partners to describe problems and solutions related during 2000–2008.* Foreign-born persons and racial/ethnic to the TB pandemic and to support worldwide TB minorities continued to bear a disproportionate burden of TB control efforts. The U.S. theme for this year’s observance disease in the United States. In 2008, the TB rate in foreign- is Partnerships for TB Elimination. -

Transmission and Evolution of Tick-Borne Viruses

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Transmission and evolution of tick-borne viruses Doug E Brackney and Philip M Armstrong Ticks transmit a diverse array of viruses such as tick-borne Bourbon viruses in the U.S. [6,7]. These trends are driven encephalitis virus, Powassan virus, and Crimean-Congo by the proliferation of ticks in many regions of the world hemorrhagic fever virus that are reemerging in many parts of and by human encroachment into tick-infested habitats. the world. Most tick-borne viruses (TBVs) are RNA viruses that In addition, most TBVs are RNA viruses that mutate replicate using error-prone polymerases and produce faster than DNA-based organisms and replicate to high genetically diverse viral populations that facilitate their rapid population sizes within individual hosts to form a hetero- evolution and adaptation to novel environments. This article geneous population of closely related viral variants reviews the mechanisms of virus transmission by tick vectors, termed a mutant swarm or quasispecies [8]. This popula- the molecular evolution of TBVs circulating in nature, and the tion structure allows RNA viruses to rapidly evolve and processes shaping viral diversity within hosts to better adapt into new ecological niches, and to develop new understand how these viruses may become public health biological properties that can lead to changes in disease threats. In addition, remaining questions and future directions patterns and virulence [9]. The purpose of this paper is to for research are discussed. review the mechanisms of virus transmission among Address vector ticks and vertebrate hosts and to examine the Department of Environmental Sciences, Center for Vector Biology & diversity and molecular evolution of TBVs circulating Zoonotic Diseases, The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, in nature. -

Bitten Enhance.Pdf

bitten. Copyright © 2019 by Kris Newby. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales pro- motional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Frontispiece: Tick research at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, in Hamilton, Mon- tana (Courtesy of Gary Hettrick, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], National Institutes of Health [NIH]) Maps by Nick Springer, Springer Cartographics Designed by William Ruoto Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Newby, Kris, author. Title: Bitten: the secret history of lyme disease and biological weapons / Kris Newby. Description: New York, NY: Harper Wave, [2019] Identifiers: LCCN 2019006357 | ISBN 9780062896278 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Lyme disease— History. | Lyme disease— Diagnosis. | Lyme Disease— Treatment. | BISAC: HEALTH & FITNESS / Diseases / Nervous System (incl. Brain). | MEDICAL / Diseases. | MEDICAL / Infectious Diseases. Classification: LCC RC155.5.N49 2019 | DDC 616.9/246—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006357 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Appendix I: Ticks and Human Disease Agents -

Zoonotic Significance and Prophylactic Measure Against Babesiosis

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2015) 4(7): 938-953 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 4 Number 7 (2015) pp. 938-953 http://www.ijcmas.com Review Article Zoonotic significance and Prophylactic Measure against babesiosis Faryal Saad, Kalimullah Khan, Shandana Ali and Noor ul Akbar* Department of Zoology, Kohat University of Science and Technology, Kohat, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Babesiosis is a vector borne disease by the different species of genus Babesia, affecting a large no of mammals worldwide. Babesiosis has zoonotic significance all over the world, causing huge loss to livestock industry and health hazards in human population. The primary zoonotic vector of babesia is ixodes ticks. Keywo rd s Different species have different virulence, infectivity and pathogenicity. Literature was collected from the individual researchers published papers. Table was made in Babesiosis , the MS excel. The present study review for the current knowledge about the Prophylactic, babesia species ecology, host specificity, life cycle and pathogenesis with an Tick borne, emphasis on the zoonotic significance and prophylactic measures against Vector, Babesiosis. Prophylactic measure against Babesiosis in early times was hindered Zoonosis. but due to advancement in research, the anti babesial drugs and vaccines have been developed. This review emphasizes on the awareness of public sector, rural communities, owners of animal husbandry and health department about the risk of infection in KPK and control measure should be implemented. Vaccines of less price tag should be designed to prevent the infection of cattles and human population. Introduction Babesiosis is a tick transmitted disease, At specie level there is considerable infecting a wide variety of wild and confusion about the true number of zoonotic domestic animals, as well as humans. -

Distribution, Seasonality, and Hosts of the Rocky Mountain Wood Tick in the United States Author(S): Angela M

Distribution, Seasonality, and Hosts of the Rocky Mountain Wood Tick in the United States Author(s): Angela M. James, Jerome E. Freier, James E. Keirans, Lance A. Durden, James W. Mertins, and Jack L. Schlater Source: Journal of Medical Entomology, 43(1):17-24. 2006. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585(2006)043[0017:DSAHOT]2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/ full/10.1603/0022-2585%282006%29043%5B0017%3ADSAHOT%5D2.0.CO %3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/ terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. SAMPLING,DISTRIBUTION,DISPERSAL Distribution, Seasonality, and Hosts of the Rocky Mountain Wood Tick in the United States ANGELA M. JAMES, JEROME E. FREIER, JAMES E. KEIRANS,1 LANCE A. DURDEN,1 2 2 JAMES W. MERTINS, AND JACK L. SCHLATER USDAÐAPHIS, Veterinary Services, Centers of Epidemiology and Animal Health, 2150 Centre Ave., Building B, Fort Collins, CO 80526Ð8117 J. -

Anaplasmosis: an Emerging Tick-Borne Disease of Importance in Canada

IDCases 14 (2018) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect IDCases journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/idcr Case report Anaplasmosis: An emerging tick-borne disease of importance in Canada a, b,c d,e e,f Kelsey Uminski *, Kamran Kadkhoda , Brett L. Houston , Alison Lopez , g,h i c c Lauren J. MacKenzie , Robbin Lindsay , Andrew Walkty , John Embil , d,e Ryan Zarychanski a Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada b Cadham Provincial Laboratory, Government of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada c Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada d Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Medical Oncology and Hematology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada e CancerCare Manitoba, Department of Medical Oncology and Hematology, Winnipeg, MB, Canada f Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Section of Infectious Diseases, Winnipeg, MB, Canada g Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Infectious Diseases, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada h Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada i Public Health Agency of Canada, National Microbiology Laboratory, Zoonotic Diseases and Special Pathogens, Winnipeg, MB, Canada A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (HGA) is an infection caused by the intracellular bacterium Received 11 September 2018 Anaplasma phagocytophilum.