University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parsifal and Canada: a Documentary Study

Parsifal and Canada: A Documentary Study The Canadian Opera Company is preparing to stage Parsifal in Toronto for the first time in 115 years; seven performances are planned for the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts from September 25 to October 18, 2020. Restrictions on public gatherings imposed as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic have placed the production in jeopardy. Wagnerians have so far suffered the cancellation of the COC’s Flying Dutchman, Chicago Lyric Opera’s Ring cycle and the entire Bayreuth Festival for 2020. It will be a hard blow if the COC Parsifal follows in the footsteps of a projected performance of Parsifal in Montreal over 100 years ago. Quinlan Opera Company from England, which mounted a series of 20 operas in Montreal in the spring of 1914 (including a complete Ring cycle), announced plans to return in the fall of 1914 for another feast of opera, including Parsifal. But World War One intervened, the Parsifal production was cancelled, and the Quinlan company went out of business. Let us hope that history does not repeat itself.1 While we await news of whether the COC production will be mounted, it is an opportune time to reflect on Parsifal and its various resonances in Canadian music history. This article will consider three aspects of Parsifal and Canada: 1) a performance history, including both excerpts and complete presentations; 2) remarks on some Canadian singers who have sung Parsifal roles; and 3) Canadian scholarship on Parsifal. NB: The indication [DS] refers the reader to sources that are reproduced in the documentation portfolio that accompanies this article. -

Fraser, C, 2018.Pdf

The PIT: A YA Response to Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature Callum Fraser Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Department of English Language, Literature and Linguistics Newcastle University i ii Abstract This project consists of a Young Adult novel — The PIT — and an accompanying critical component, titled Miltonic Ideas of the Fall in Romantic Literature. The novel follows the story of a teenage boy, Jack, a naturally talented artist struggling to understand his place in a dystopian future society that only values ‘productive’ work and regards art as worthless. Throughout the novel, we see Jack undergo a ‘coming of age’, where he moves from being an essentially passive character to one empowered with a sense of courage and a clearer sense of his own identity. Throughout this process we see him re-evaluate his understanding of friendship, love, and loyalty to authority. The critical component of the thesis explores the influence of John Milton’s epic poem, Paradise Lost, on a range of Romantic writers. Specifically, the critical work examines the way in which these Romantic writers use the Fall, and the notion of ‘falleness’ — as envisioned in Paradise Lost — as a model for writing about their roles as poets/writers in periods of political turmoil, such as the aftermath of the French Revolution, and the cultural transition between what we now regard as the Romantic and Victorian periods. The thesis’s ‘bridging chapter’ explores the connection between these two components. It discusses how the conflicted poet figures and divided narratives discussed in the critical component provide a model for my own novel’s exploration of adolescent growth within a society that seeks to restrict imaginative freedom. -

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23Rd to 27Th September 2020

International Richard Wagner Congress – Bonn 23rd to 27th September 2020 Imprint The Richard Wagner Congress 2020 Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn e.V. programme Andreas Loesch (Vorsitzender) John Peter (stellv. Vorsitzender) was created in collaboration with Zanderstraße 47, 53177 Bonn Tel. +49-(0)178-8539559 [email protected] Organiser / booking details ARS MUSICA Musik- und Kulturreisen GmbH Bachemer Straße 209, 50935 Köln Tel: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 00 Fax: +49-(0)221-16 86 53 01 [email protected] RICHARD-WAGNER-VERBAND BONN E.V. and is sponsored by Image sources frontpage from left to right, from top to bottom - Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Deutsche Post / Richard-Wagner-Verband Bonn - StadtMuseum Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Beethovenhaus Bonn - Stadt Königswinter - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Stadtmuseum Siegburg - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn Current information about the program backpage - Michael Sondermann/Bundesstadt Bonn rwv-bonn.de/kongress-2020 Congress Programme for all Congress days 2 p.m. | Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Dear Members of the Richard Wagner Societies, dear Friends of Richard Wagner’s Music, Conference Hotel Hilton Richard Wagner – en miniature Symposium: »Beethoven, Wagner and the political “Welcome” to the Congress of the International Association of Richard Wagner Societies in 2020, commemorating Ludwig “Der Meister” depicted on stamps movements of their time « (simultaneous translation) van Beethoven’s 250th birthday worldwide. Richard Wagner appreciated him more than any other composer in his life, which Prof. Dr. Dieter Borchmeyer, PD Dr. Ulrike Kienzle, is why the Congress in Bonn, Beethoven’s hometown, is going to centre on “Beethoven and Wagner”. -

Wagner and Bayreuth Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Brahms and Detmold

MUSIC DOCUMENTARY 30 MIN. VERSIONS Wagner and Bayreuth Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) No city in the world is so closely identified with a composer as Bayreuth is with Richard Wag- ner. Towards the end of the 19th century Richard Wagner had a Festival Theatre built here and RIGHTS revived the Ancient Greek idea of annual festivals. Nowadays, these festivals are attended by Worldwide, VOD, Mobile around 60,000 people. ORDER NUMBER 66 3238 VERSIONS Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Berlin Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Felix Mendelssohn, one of the most important composers of the 19th century, was influenced decisively by Berlin, which gave shape to the form and development of his music. The televi- RIGHTS sion documentary traces Mendelssohn’s life in the Berlin of the 19th century, as well as show- Worldwide, VOD, Mobile ing the city today. ORDER NUMBER 66 3305 VERSIONS Brahms and Detmold Arabic, English, French, German, Portuguese, Spanish (01 x 30 min.) Around the middle of the 19th century Detmold, a small town in the west of Germany, was a centre of the sort of cultural activity that would normally be expected only of a large city. An RIGHTS artistically-minded local prince saw to it that famous artists came to Detmold and performed in Worldwide, VOD, Mobile the theatre or at his court. For several years the town was the home of composer Johannes Brahms. Here, as Court Musician, he composed some of his most beautiful vocal and instru- ORDER NUMBER ment works. 66 3237 dw-transtel.com Classics | DW Transtel. -

Wagner in Comix and 'Toons

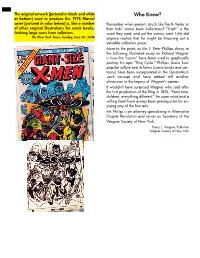

- The original artwork [pictured in black and white Who Knew? at bottom] used to produce the 1975 Marvel cover [pictured in color below] is, like a number Remember when parents struck like Darth Vader at of other original illustrations for comic books, their kids’ comic book collections? “Trash” is the fetching large sums from collectors. word they used, and out the comics went. Little did The New York Times, Sunday, June 30, 2008 anyone realize that he might be throwing out a valuable collectors piece. More to the point, as Mr. F. Peter Phillips shows in the following illustrated essay on Richard Wagner is how the “comix” have been used to graphically portray his epic “Rng Cycle.” Phillips shows how popular culture and its forms (comic books and car- toons) have been incorporated in the Gesamtkust- werk concept and have added still another dimension to the legacy of Wagner’s operas. It wouldn’t have surprised Wagner who said after the first production of the Ring in 1876, “Next time, children, everything different.” An open mind and a willing heart have always been prerequisites for en- joying any of the fine arts. Mr. Phllips is an attorney specializing in Alternative Dispute Resolution and serves as Secretary of the Wagner Society of New York. Harry L. Wagner, Publisher Wagner Society of New York Wagner in Comix and ‘Toons By F. Peter Phillips Recent publications have revealed an aspect of Wagner-inspired literature that has been grossly overlooked—Wagner in graphic art (i.e., comics) and in animated cartoons. The Ring has been ren- dered into comics of substantial integrity at least three times in the past two decades, and a recent scholarly study of music used in animated cartoons has noted uses of Wagner’s music that suggest that Wagner’s influence may even more profoundly im- bued in our culture than we might have thought. -

Wagner: Das Rheingold

as Rhe ai Pu W i D ol til a n ik m in g n aR , , Y ge iin s n g e eR Rg s t e P l i k e R a a e Y P o V P V h o é a R l n n C e R h D R ü e s g t a R m a e R 2 Das RheingolD Mariinsky Richard WAGNER / Рихард ВагнеР 3 iii. Nehmt euch in acht! / Beware! p19 7’41” (1813–1883) 4 iv. Vergeh, frevelender gauch! – Was sagt der? / enough, blasphemous fool! – What did he say? p21 4’48” 5 v. Ohe! Ohe! Ha-ha-ha! Schreckliche Schlange / Oh! Oh! Ha ha ha! terrible serpent p21 6’00” DAs RhEingolD Vierte szene – scene Four (ThE Rhine GolD / Золото Рейна) 6 i. Da, Vetter, sitze du fest! / Sit tight there, kinsman! p22 4’45” 7 ii. Gezahlt hab’ ich; nun last mich zieh’n / I have paid: now let me depart p23 5’53” GoDs / Боги 8 iii. Bin ich nun frei? Wirklich frei? / am I free now? truly free? p24 3’45” Wotan / Вотан..........................................................................................................................................................................René PaPe / Рене ПАПЕ 9 iv. Fasolt und Fafner nahen von fern / From afar Fasolt and Fafner are approaching p24 5’06” Donner / Доннер.............................................................................................................................................alexei MaRKOV / Алексей Марков 10 v. Gepflanzt sind die Pfähle / These poles we’ve planted p25 6’10” Froh / Фро................................................................................................................................................Sergei SeMISHKUR / Сергей СемишкуР loge / логе..................................................................................................................................................Stephan RügaMeR / Стефан РюгАМЕР 11 vi. Weiche, Wotan, weiche! / Yield, Wotan, yield! p26 5’39” Fricka / Фрикка............................................................................................................................ekaterina gUBaNOVa / Екатерина губАновА 12 vii. -

The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology

A-R Online Music Anthology www.armusicanthology.com Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, Part 2: Nationalism and Ideology Joseph E. Jones is Associate Professor at Texas A&M by Joseph E. Jones and Sarah Marie Lucas University-Kingsville. His research has focused on German opera, especially the collaborations of Strauss Texas A&M University-Kingsville and Hofmannsthal, and Viennese cultural history. He co- edited Richard Strauss in Context (Cambridge, 2020) Assigned Readings and directs a study abroad program in Austria. Core Survey Sarah Marie Lucas is Lecturer of Music History, Music Historical and Analytical Perspectives Theory, and Ear Training at Texas A&M University- Composer Biographies Kingsville. Her research interests include reception and Supplementary Readings performance history, as well as sketch studies, particularly relating to Béla Bartók and his Summary List collaborations with the conductor Fritz Reiner. Her work at the Budapest Bartók Archives was supported by a Genres to Understand Fulbright grant. Musical Terms to Understand Contextual Terms, Figures, and Events Main Concepts Scores and Recordings Exercises This document is for authorized use only. Unauthorized copying or posting is an infringement of copyright. If you have questions about using this guide, please contact us: http://www.armusicanthology.com/anthology/Contact.aspx Content Guide: The Nineteenth Century, Part 2 (Nationalism and Ideology) 1 ______________________________________________________________________________ Content Guide The Nineteenth Century, -

Brief History of English and American Literature

Brief History of English and American Literature Henry A. Beers Brief History of English and American Literature Table of Contents Brief History of English and American Literature..........................................................................................1 Henry A. Beers.........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION...................................................................................................................................6 PREFACE................................................................................................................................................9 CHAPTER I. FROM THE CONQUEST TO CHAUCER....................................................................11 CHAPTER II. FROM CHAUCER TO SPENSER................................................................................22 CHAPTER III. THE AGE OF SHAKSPERE.......................................................................................34 CHAPTER IV. THE AGE OF MILTON..............................................................................................50 CHAPTER V. FROM THE RESTORATION TO THE DEATH OF POPE........................................63 CHAPTER VI. FROM THE DEATH OF POPE TO THE FRENCH REVOLUTION........................73 CHAPTER VII. FROM THE FRENCH REVOLUTION TO THE DEATH OF SCOTT....................83 CHAPTER VIII. FROM THE DEATH OF SCOTT TO THE PRESENT TIME.................................98 CHAPTER -

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers by Bwaar Omer

The Impact of the Third Reich on Famous Composers By Bwaar Omer Germany is known as a land of poets and thinkers and has been the origin of many great composers and artists. In the early 1920s, the country was becoming a hub for artists and new music. In the time of the Weimar Republic during the roaring twenties, jazz music was a symbol of the time and it was used to represent the acceptance of the newly introduced cultures. Many conservatives, however, opposed this rise of for- eign culture and new music. Guido Fackler, a German scientist, contends this became a more apparent issue when Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) took power in 1933 and created the Third Reich. The forbidden music during the Third Reich, known as degen- erative music, was deemed to be anti-German and people who listened to it were not considered true Germans by nationalists. A famous composer who was negatively affected by the brand of degenerative music was Kurt Weill (1900-1950). Weill was a Jewish composer and playwright who was using his com- positions and stories in order to expose the Nazi agenda and criticize society for not foreseeing the perils to come (Hinton par. 11). Weill was exiled from Germany when the Nazi party took power and he went to America to continue his career. While Weill was exiled from Germany and lacked power to fight back, the Nazis created propaganda to attack any type of music associated with Jews and blacks. The “Entartete Musik” poster portrays a cartoon of a black individual playing a saxo- phone whose lips have been enlarged in an attempt to make him look more like an animal rather than a human. -

Late Romantic Period 1850-1910 • Characteristics of Romantic Period

Late Romantic Period 1850-1910 • Characteristics of Romantic Period o Emotion design over intellectual design o Individual over society o Music increased in length and changed emotion often in the same piece • Hector Berlioz (1803-1869) o French composer o Known for writing for large orchestras, sometimes over 1000 musicians o An Episode in the Life of an Artist (Symphonie Fantastique) • Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow. • Richard Wagner (1813-1883) o German composer and theatre director o Known for opera – big dramatic works • Built his own opera house in order to be able to accommodate his works • Subjects drawn from Norse mythology o Lohengrin – Bridal Chorus o Die Walkure • Franz Liszt (1811-1886) o Hungarian composer and virtuoso pianist o Used gypsy music as basis for compositions o Created modern piano playing technique o Invented the form of Symphonic Poem or Tone Poem Music based on art, literature, or other “nonmusical” idea One movement with several ‘ideas’ that move freely throughout the piece o Hungarian Rhapsody No. -

Ebook Download Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around

WAGNERS RING TURNING THE SKY AROUND - AN INTRODUCTION TO THE RING OF THE NIBELUNG 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK M Owen Lee | 9780879101862 | | | | | Wagners Ring Turning the Sky Around - An Introduction to the Ring of the Nibelung 1st edition PDF Book It is even possible for the orchestra to convey ideas that are hidden from the characters themselves—an idea that later found its way into film scores. Unfamiliarity with Wagner constitutes an ignorance of, well, Wagnerian proportions. Some of my friends have seen far more than these. This section does not cite any sources. Digital watches chime the hour in half-diminished seventh chords. The daughters of the Rhine come up and pull Hagen into the depth of the Rhine. The plot synopses were helpful, but some of the deep psychological analysis was a bit boring. Next he encounters Wotan his grandfather , quarrels with him and cuts Wotan's staff of power in half. The next possessor of the ring, the giant Fafner, consumed with greed and lust for power, kills his brother, Fasolt, taking the spoils to the deep forest while the gods enter Valhalla to some of the most glorious and ironically triumphant music imaginable. Has underlining on pages. John shares his recipe for Nectar of the Gods. April Learn how and when to remove this template message. It's actually OK because that's what Wotan decreed for her anyway: First one up there shall have you. See Article History. Politics and music often go together. It left me at a whole new level of self-awareness, and has for all the years that have followed given me pleasures and insights that have enriched my life. -

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan Und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding)

4. Wagner Prelude to Tristan und Isolde (For Unit 6: Developing Musical Understanding) Background information and performance circumstances Richard Wagner (1813-1883) was the greatest exponent of mid-nineteenth-century German romanticism. Like some other leading nineteenth-century musicians, but unlike those from previous eras, he was never a professional instrumentalist or singer, but worked as a freelance composer and conductor. A genius of over-riding force and ambition, he created a new genre of ‘music drama’ and greatly expanded the expressive possibilities of tonal composition. His works divided musical opinion, and strongly influenced several generations of composers across Europe. Career Brought up in a family with wide and somewhat Bohemian artistic connections, Wagner was discouraged by his mother from studying music, and at first was drawn more to literature – a source of inspiration he shared with many other romantic composers. It was only at the age of 15 that he began a secret study of harmony, working from a German translation of Logier’s School of Thoroughbass. [A reprint of this book is available on the Internet - http://archive.org/details/logierscomprehen00logi. The approach to basic harmony, remarkably, is very much the same as we use today.] Eventually he took private composition lessons, completing four years of study in 1832. Meanwhile his impatience with formal training and his obsessive attention to what interested him led to a succession of disasters over his education in Leipzig, successively at St Nicholas’ School, St Thomas’ School (where Bach had been cantor), and the university. At the age of 15, Wagner had written a full-length tragedy, and in 1832 he wrote the libretto to his first opera.