Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seeds and Plants Imported

Issued November 9,1915. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. WILLIAM A. TAYLOR, Chief of Bureau. INVENTORY SEEDS AND PLANTS IMPORTED OFFICE OF FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION DURING THE PERIOD FROM APRIL 1 " " TO JUNE 30,1913. " , r (No. 35; Nos. 35136 TO 3566^..,--"•-****"*"' WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1915. Issued November 9,1915. U. S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. WILLIAM A. TAYLOR, Chief of Bureau. INVENTORY SEEDS AND PLANTS IMPORTED BY THE OFFICE OF FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION DURING THE PERIOD FROM APRIL 1 TO JUNE 30,1913. (No. 35; Nos. 35136 TO 35666.) WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1915. BUREAU OF PLANT INDUSTRY. Chief of Bureau, WILLIAM A. TAYLOR. Assistant Chief of Bureau, KARL F. KELLERMAN. Officer in Charge of Publications, J. E. ROCKWELL. Chief Clerk, JAMES E. JONES. FOREIGN SEED AND PLANT INTRODUCTION. SCIENTIFIC STAFF. David Fairchild, Agricultural Explorer in Charge. P. H. Dorsett, Plant Introducer, in Charge of Plant Introduction Field Stations. Peter Bisset, Plant Introducer, in Charge of Foreign Plant Distribution. Frank N. Meyer and Wilson Popenoe, Agricultural Explorers. H. C. Skeels, S. C. Stuntz, and R. A. Young, Botanical Assistants. Allen M. Groves, Nathan Menderson, and Glen P. Van Eseltine, Assistants. Robert L. Beagles, Superintendent, Plant Introduction Field Station, Chico, Cal. Edward Simmonds, Superintendent, Subtropical Plant Introduction Field Station, Miami, Fla. John M. Rankin, Superintendent, Yarrow Plant Introduction Field Station, Rockville, Md. E. R. Johnston, Assistant in Charge, Plant Introduction Field Station, Brooksville, Fla. Edward Goucher and H. Klopfer, Plant Propagators. Collaborators: Aaron Aaronsohn, Director, Jewish Agricultural Experimental Station, Haifa, Palestine; Thomas W. -

Chagrin River Watershed Action Plan

Chagrin River Watershed Action Plan Chagrin River Watershed Partners, Inc. PO Box 229 Willoughby, Ohio 44096 (440) 975-3870 (Phone) (440) 975- 3865 (Fax) www.crwp.org Endorsed by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and Ohio Department of Natural Resources on December 18, 2006 Revised December 2009 Updated September 2011 i List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... vi List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. vii List of Appendices ..................................................................................................................................... viii Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................... x Endorsement of Plan by Watershed Stakeholders ....................................................................................... xi List of Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................ xii 1 Chagrin River Watershed ............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Administrative Boundaries .......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 History of Chagrin -

Epimedium L) – a Promising Source of Raw Materials for the Creation of Medicines for the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction in Men

Pharmacogn J. 2020; 12(6)Suppl:1710-1715 A Multifaceted Journal in the field of Natural Products and Pharmacognosy Research Article www.phcogj.com Representatives of the Genus Goryanka (Epimedium L) – a Promising Source of Raw Materials for the Creation of Medicines for the Treatment of Erectile Dysfunction in Men Bukinich Darya Dmitrievna, Salova VG, Odintsova EB, Rastopchina OV, Solovyovа NL, Kozlova AM, Krasniuk II (jun), Krasniuk II, Kozlova Zh M* ABSTRACT Erectile dysfunction and multiple mechanisms of its development are one of the most pressing problems of modern medicine. In the twenty-first century, millions of men around the world suffer from sexual disorders, and the number of such patients is only growing from year to Bukinich Darya Dmitrievna, year. The flavonoid icariin, contained in plants of the genusEpimedium L., is a promising Salova VG, Odintsova EB, pharmacologically active substance used for erectile dysfunction, due to its ability to affect Rastopchina OV, Solovyovа type 5 phosphodiesterase, inhibiting its activity. To date, domestic and foreign pharmaceutical NL, Kozlova AM, Krasniuk II companies produce biologically active food additives and herbal preparations, which include (jun), Krasniuk II, Kozlova Zh Goryanka extract. But the range of standardized herbal medicines is very small. M* Key words: Drug, Epimedium Estrellita, Icariin, Impotence. First Moscow state medical university named after I.M. Sechenov, (Sechenov University), Moscow, RUSSIAN INTRODUCTION The purpose of this work is to theoretically FEDERATION. substantiate the possibility of using medicinal plant Erectile dysfunction (ED) is one of the most raw materials of the genus Goryanka (Epimedium Correspondence pressing problems of modern medicine. According L) to create medicines for the treatment of erectile Kozlova Zh. -

Cleveland Tree Plan Appendix a – Guide for Species Selection

Appendix A A Guide for Species Selection Managing trees in a changing climate is challenging for arborists Right Tree Right Place. Improperly siting trees can result and urban foresters. Species that are currently thriving could decline in economic, environmental, and social losses to the as future climatic conditions alter weather events and patterns. community. The “right tree right place” maxim is central Local knowledge and expertise of Cleveland’s urban forest was to changing the conversation around trees, specifically with utilized to produce the following guide for the selection of trees that respect to thinking of trees as assets versus liabilities (Arbor can tolerate extreme environmental conditions. Day Foundation). Tree planting and transplanting projects Trees were selected and compiled into a recommended species list should carefully consider plant characteristics at maturity, for Cleveland’s urban forest by Holden Arboretum’s Plant above- and below-ground site factors, and urban forest Collection and Records Curators. This list is intended to aid species composition. selection for public and private land across the community with A unique tool is also available to assess the urban site index consideration given to trees that tolerate urban conditions like (USI) developed by regional urban foresters at the Ohio compaction, drought, pollution, and salt. Department of Natural Resources Division of Forestry Specific characteristics were considered in selecting species that (Leibowitz 2012). The tool utilizes a rapid assessment of could collectively contribute to a more sustainable urban and factors to score sites between 0 and 20 as a means to community forest, including the promotion of diversity, selective identify planting suitability. -

The Nordic Arboretum Expedition to South Korea 1976

THE NORDIC ARBORETUM EXPEDITION TO SOUTH KOREA 1976 Max. E. Hagman Lars Feilberg Tomas Lagerström Jan Sanda HELSINKI 1978 "... I of the am painfully conscious demerits of this work, but believing that, on the whole, it reflects fairly faith fully the regions of which it treats, I venture to present it to the and to ask for it the same and lenient public? kindly critislsm with which my records of travel in the East and else where have hitherto been and that it received, may be accepted to make the as an honest attempt a contribution to sum of knowledge of Korea and its people and describe things as I saw them. .." Isabella L. Bishop, Korea and Her Neighbours, 1897. This report has bean prepared at the Department of Forest genetics, Forest Research Institute Unioninkatu 40 A, Helsinki, Finland THE NORDIC ARBORETUM EXPEDITION TO SOUTH KOREA 1976 Max. Hagman Lars Feilberg Tomas Lagerström Jan E. Sanda HELSINKI 1978 THE NORDIC ARBORETUM EXPEDITION TO SOUTH KOREA 1976 MAX, HAGMAN LARS FEILBERG TOMAS LAGERSTRÖM JAN E. SANDA Contents 2 Foreword and acknowledgements p. work in Denmark and Korea 7 Preparatory Finland, p. Itinerary and time table p. 9 Korean forestry and forestry research p. 15 Korean arboreta and vegetation research p. 19 22 Climate and ecology p. Collection localities p. 26 Material collected p. 70 and distribution of seeds and Handling plants p. 71 Suggestions for foorther activities p. 74 76 Bibliography p. Adresses of and institutions 80 persons p. Statement of accounts p. 82 Appendix:Maps and seed list p. 84 Front-cover: The Ose-am in B. -

A Systematic Study on DNA Barcoding of Medicinally Important Genus Epimedium L

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article A Systematic Study on DNA Barcoding of Medicinally Important Genus Epimedium L. (Berberidaceae) Mengyue Guo 1 , Yanqin Xu 2, Li Ren 1, Shunzhi He 3 and Xiaohui Pang 1,* 1 Key Lab of Chinese Medicine Resources Conservation, State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine of the People’s Republic of China, Institute of Medicinal Plant Development, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College, Beijing 100193, China; [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (L.R.) 2 College of Pharmacy, Jiangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nanchang 330004, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmacy, Guiyang College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Guiyang 550002, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-57833051 Received: 27 October 2018; Accepted: 10 December 2018; Published: 17 December 2018 Abstract: Genus Epimedium consists of approximately 50 species in China, and more than half of them possess medicinal properties. The high similarity of species’ morphological characteristics complicates the identification accuracy, leading to potential risks in herbal efficacy and medical safety. In this study, we tested the applicability of four single loci, namely, rbcL, psbA-trnH, internal transcribed spacer (ITS), and ITS2, and their combinations as DNA barcodes to identify 37 Epimedium species on the basis of the analyses, including the success rates of PCR amplifications and sequencing, specific genetic divergence, distance-based method, and character-based method. Among them, character-based method showed the best applicability for identifying Epimedium species. As for the DNA barcodes, psbA-trnH showed the best performance among the four single loci with nine species being correctly differentiated. -

Native Or Suitable Plants City of Mccall

Native or Suitable Plants City of McCall The following list of plants is presented to assist the developer, business owner, or homeowner in selecting plants for landscaping. The list is by no means complete, but is a recommended selection of plants which are either native or have been successfully introduced to our area. Successful landscaping, however, requires much more than just the selection of plants. Unless you have some experience, it is suggested than you employ the services of a trained or otherwise experienced landscaper, arborist, or forester. For best results it is recommended that careful consideration be made in purchasing the plants from the local nurseries (i.e. Cascade, McCall, and New Meadows). Plants brought in from the Treasure Valley may not survive our local weather conditions, microsites, and higher elevations. Timing can also be a serious consideration as the plants may have already broken dormancy and can be damaged by our late frosts. Appendix B SELECTED IDAHO NATIVE PLANTS SUITABLE FOR VALLEY COUNTY GROWING CONDITIONS Trees & Shrubs Acer circinatum (Vine Maple). Shrub or small tree 15-20' tall, Pacific Northwest native. Bright scarlet-orange fall foliage. Excellent ornamental. Alnus incana (Mountain Alder). A large shrub, useful for mid to high elevation riparian plantings. Good plant for stream bank shelter and stabilization. Nitrogen fixing root system. Alnus sinuata (Sitka Alder). A shrub, 6-1 5' tall. Grows well on moist slopes or stream banks. Excellent shrub for erosion control and riparian restoration. Nitrogen fixing root system. Amelanchier alnifolia (Serviceberry). One of the earlier shrubs to blossom out in the spring. -

Tagawa Gardens June Snow Giant Dogwood

June Snow Giant Dogwood Cornus controversa 'June Snow-JFS' Height: 30 feet Spread: 40 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 4 Description: June Snow Giant Dogwood flowers Covered with lovely white flower clusters in spring; a Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder large rounded form, with gracefully layered branches make this tree an excellent specimen; attractive fruit in late summer turns deep blue-black; orange to red fall color Ornamental Features June Snow Giant Dogwood features showy clusters of white flowers held atop the branches in late spring. It has dark green foliage throughout the season. The pointy leaves turn an outstanding dark red in the fall. It produces navy blue berries from early to late fall. The warty gray bark and green branches add an interesting dimension to the landscape. June Snow Giant Dogwood in bloom Landscape Attributes Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder June Snow Giant Dogwood is a deciduous tree with a stunning habit of growth which features almost oriental horizontally-tiered branches. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This is a relatively low maintenance tree, and should only be pruned after flowering to avoid removing any of the current season's flowers. It is a good choice for attracting birds to your yard. It has no significant negative characteristics. June Snow Giant Dogwood is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Accent - Shade Planting & Growing June Snow Giant Dogwood will grow to be about 30 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 40 feet. -

Drought Tolerant Trees

Drought Tolerant Trees By Jessamyn Tuttle January 4, 2019 Tree choices for wet winters and dry summers Western Washington has long had a weather pattern of wet winters and dry summers, but if it seemed like the past couple of summers were warmer and dryer than usual, you're right. Many gardeners in the Pacific Northwest have noticed trees, both in their gardens and in the wilderness, wilting, getting leaf burn or insect infestations, even dying. Months without water can be fatal to many plants. When a plant dries out, the stomata on the leaves close up. Stomata allow transpiration, the loss of water through leaves, which helps the plant cool itself. Also, lack of water can increase nutrient deficiency. Eventually symptoms will manifest like leaf scorch on edges, wilted leaves, leaf drop and eventually twig dieback. A tree may survive drought stress after one season but die after several drought exposures. Younger, less established trees are more likely to die. And a drought stressed tree is more likely to succumb to insect damage or disease. The two-spotted spider mite, for example, loves hot and dry conditions. Even fungal diseases, often associated with damp conditions, may set into wood which was damaged years previously from drought. Despite this, the occasional dry spell isn't much of an issue, but the kind of drought we're starting to see may be getting worse. According to some climate projections, annual average global temperatures could rise between 1.5 and 7 degrees Celsius (2.7 to 12.6 degrees Fahrenheit), and it's expected that winters will be wetter, and summers will be dryer. -

2. ACER Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 1054. 1753. 枫属 Feng Shu Trees Or Shrubs

Fl. China 11: 516–553. 2008. 2. ACER Linnaeus, Sp. Pl. 2: 1054. 1753. 枫属 feng shu Trees or shrubs. Leaves mostly simple and palmately lobed or at least palmately veined, in a few species pinnately veined and entire or toothed, or pinnately or palmately 3–5-foliolate. Inflorescence corymbiform or umbelliform, sometimes racemose or large paniculate. Sepals (4 or)5, rarely 6. Petals (4 or)5, rarely 6, seldom absent. Stamens (4 or 5 or)8(or 10 or 12); filaments distinct. Carpels 2; ovules (1 or)2 per locule. Fruit a winged schizocarp, commonly a double samara, usually 1-seeded; embryo oily or starchy, radicle elongate, cotyledons 2, green, flat or plicate; endosperm absent. 2n = 26. About 129 species: widespread in both temperate and tropical regions of N Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central and North America; 99 species (61 endemic, three introduced) in China. Acer lanceolatum Molliard (Bull. Soc. Bot. France 50: 134. 1903), described from Guangxi, is an uncertain species and is therefore not accepted here. The type specimen, in Berlin (B), has been destroyed. Up to now, no additional specimens have been found that could help clarify the application of this name. Worldwide, Japanese maples are famous for their autumn color, and there are over 400 cultivars. Also, many Chinese maple trees have beautiful autumn colors and have been cultivated widely in Chinese gardens, such as Acer buergerianum, A. davidii, A. duplicatoserratum, A. griseum, A. pictum, A. tataricum subsp. ginnala, A. triflorum, A. truncatum, and A. wilsonii. In winter, the snake-bark maples (A. davidii and its relatives) and paper-bark maple (A. -

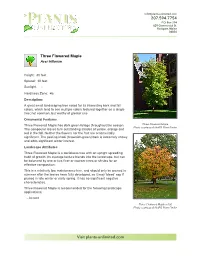

Plants Unlimited Three Flowered Maple

[email protected] 207.594.7754 P.O. Box 374 629 Commercial St. Rockport, Maine 04856 Three Flowered Maple Acer triflorum Height: 30 feet Spread: 30 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 4a Description: A great small landscaping tree noted for its interesting bark and fall colors, which tend to see multiple colors featured together on a single tree; not common, but worthy of greater use Ornamental Features Three Flowered Maple has dark green foliage throughout the season. Three Flowered Maple Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder The compound leaves turn outstanding shades of yellow, orange and red in the fall. Neither the flowers nor the fruit are ornamentally significant. The peeling khaki (brownish-green) bark is extremely showy and adds significant winter interest. Landscape Attributes Three Flowered Maple is a deciduous tree with an upright spreading habit of growth. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This is a relatively low maintenance tree, and should only be pruned in summer after the leaves have fully developed, as it may 'bleed' sap if pruned in late winter or early spring. It has no significant negative characteristics. Three Flowered Maple is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Accent Three Flowered Maple in fall Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder Visit plants-unlimited.com [email protected] 207.594.7754 P.O. Box 374 629 Commercial St. Rockport, Maine 04856 Planting & Growing Three Flowered Maple will grow to be about 30 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 30 feet. -

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to Identify the Level of Threat to Plants

Ex-Situ Conservation at Scott Arboretum Public gardens and arboreta are more than just pretty places. They serve as an insurance policy for the future through their well managed ex situ collections. Ex situ conservation focuses on safeguarding species by keeping them in places such as seed banks or living collections. In situ means "on site", so in situ conservation is the conservation of species diversity within normal and natural habitats and ecosystems. The Scott Arboretum is a member of Botanical Gardens Conservation International (BGCI), which works with botanic gardens around the world and other conservation partners to secure plant diversity for the benefit of people and the planet. The aim of BGCI is to ensure that threatened species are secure in botanic garden collections as an insurance policy against loss in the wild. Their work encompasses supporting botanic garden development where this is needed and addressing capacity building needs. They support ex situ conservation for priority species, with a focus on linking ex situ conservation with species conservation in natural habitats and they work with botanic gardens on the development and implementation of habitat restoration and education projects. BGCI uses the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ to identify the level of threat to plants. In-depth analyses of the data contained in the IUCN, the International Union for Conservation of Nature, Red List are published periodically (usually at least once every four years). The results from the analysis of the data contained in the 2008 update of the IUCN Red List are published in The 2008 Review of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; see www.iucn.org/redlist for further details.