Balangiga Massacre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to loe removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI* Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 WASHINGTON IRVING CHAMBERS: INNOVATION, PROFESSIONALIZATION, AND THE NEW NAVY, 1872-1919 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctorof Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Stephen Kenneth Stein, B.A., M.A. -

An Analysis of US Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization During

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2017 Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 Laurence M. Nelson III Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Nelson, Laurence M. III, "Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934" (2017). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 6536. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/6536 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INNOVATION IN INTELLIGENCE: AN ANALYSIS OF U.S. MARINE CORPS INTELLIGENCE MODERNIZATION DURING THE OCCUPATION OF HAITI, 1915-1934 by Laurence Merl Nelson III A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Robert McPherson, Ph.D. James Sanders, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Jeannie Johnson, Ph.D. Mark R. McLellan, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2017 ii Copyright © Laurence Merl Nelson III 2017 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Innovation in Intelligence: An Analysis of U.S. Marine Corps Intelligence Modernization during the Occupation of Haiti, 1915-1934 by Laurence M. -

The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900

07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 1 11/19/08 12:53:03 PM 07-02574 China Relief Cover.indd 2 11/19/08 12:53:04 PM The China Relief Expedition Joint Coalition Warfare in China Summer 1900 prepared by LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory This essay reflects the views of the author alone and does not necessarily imply concurrence by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHU/APL) or any other organization or agency, public or private. About the Author LTC(R) Robert R. Leonhard, Ph.D., is on the Principal Professional Staff of The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and a member of the Strategic Assessments Office of the National Security Analysis Department. He retired from a 24-year career in the Army after serving as an infantry officer and war planner and is a veteran of Operation Desert Storm. Dr. Leonhard is the author of The Art of Maneuver: Maneuver-Warfare Theory and AirLand Battle (1991), Fighting by Minutes: Time and the Art of War (1994), The Principles of War for the Informa- tion Age (1998), and The Evolution of Strategy in the Global War on Terrorism (2005), as well as numerous articles and essays on national security issues. Foreign Concessions and Spheres of Influence China, 1900 Introduction The summer of 1900 saw the formation of a perfect storm of conflict over the northern provinces of China. Atop an anachronistic and arrogant national government sat an aged and devious woman—the Empress Dowager Tsu Hsi. -

Abbott, Judge , of Salem, N. J., 461 Abeel Family, N. Y., 461

INDEX Abbott, Judge , of Salem, N. J., 461 Alexandria, Va., 392 Abeel family, N. Y., 461 Alleghany County: and Pennsylvania Abercrombie, Charlotte and Sophia, 368 Canal, 189, 199 (n. 87) ; and Whiskey Abercrombie, James, 368 Rebellion, 330, 344 Abington Meeting, 118 Alleghany River, proposals to connect by Abolition movement, 119, 313, 314, 352, water with Susquehanna River and Lake 359; contemporary attitude toward, Erie, 176-177, 180, 181, 190, 191, 202 145; in Philadelphia, 140, 141; meeting Allen, James, papers, 120 in Boston (1841), 153. See also under Allen, Margaret Hamilton (Mrs. Wil- Slavery liam), portrait attributed to James Clay- Academy of Natural Sciences, library, 126 poole, 441 (n. 12) Accokeek Lands, 209 Allen, William, 441 (n. 12) ; papers, 120, Adams, Henry, History of the United 431; petition to, by William Moore, States . , 138-139 and refusal, 119 Adams, John: feud with Pickering, 503; Allen, William Henry, letters, 271 on conditions in Pennsylvania, 292, 293, Allhouse, Henry, 203 (n. 100) 300, 302; on natural rights, 22 Allinson, Samuel, 156, 157 Adams, John Quincy: position on invasion Allinson, William, 156, 157 of Florida, 397; President of U. S., 382, Almanacs, 465, 477, 480, 481-482 408, 409, 505, 506; presidential candi- Ambrister, Robert, 397-398 date, 407, 502-503, 506 American Baptist Historical Society, 126 Adams, John Stokes, Autobiographical American Catholic Historical Society of Sketch by John Marshall edited by, re- Philadelphia, 126 viewed, 414-415 American Historical Association: Little- Adams and Loring, 210 ton-Griswold committee, publication of Adams County, 226; cemetery inscriptions, Bucks Co. court records, 268; meeting, 273 address by T. -

Us Marines, Manhood, and American Culture, 1914-1924

THE GLOBE AND ANCHOR MEN: U.S. MARINES, MANHOOD, AND AMERICAN CULTURE, 1914-1924 by MARK RYLAND FOLSE ANDREW J. HUEBNER, COMMITTEE CHAIR DANIEL RICHES LISA DORR JOHN BEELER BETH BAILEY A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2018 Copyright Mark Ryland Folse 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that between 1914 and 1924, U.S. Marines made manhood central to the communication of their image and culture, a strategy that underpinned the Corps’ effort to attract recruits from society and acquire funding from Congress. White manhood informed much of the Marines’ collective identity, which they believed set them apart from the other services. Interest in World War I, the campaigns in Hispaniola, and the development of amphibious warfare doctrine have made the Marine Corps during this period the focus of traditional military history. These histories often neglect a vital component of the Marine historical narrative: the ways Marines used masculinity and race to form positive connections with American society. For the Great War-era Marine Corps, those connections came from their claims to make good men out of America’s white youngsters. This project, therefore, fits with and expands the broader scholarly movement to put matters of race and gender at the center of military history. It was along the lines of manhood that Marines were judged by society. In France, Marines came to represent all that was good and strong in American men. -

THE BELLS of BALANGIGA Journey Home a Tale of Tenacity and Truth by Rear Admiral Daniel W

THE BELLS OF BALANGIGA Journey Home A Tale of Tenacity and Truth by Rear Admiral Daniel W. McKinnon, Jr., SC, U.S. Navy (Retired) The three “Bells of Balangiga” on display in front of the church of San Lorenzo de Martir, Balangiga, Eastern Samar, Republic of the Philippines. The two bells on the left are those that became the famous “Bells of Balangiga.” The smaller one on the right, the “Manchu Bell,” discovered to be the real signal bell, joining the others with all now known as, “The Bells of Balangiga.” This is a story about three sailors who were able to achieve the return of two Bells to the Church of San Lorenzo de Martir in the coastal town of Balangiga, Province of Easter Samar, Republic of the Philippines, from a museum on a United States Air Force (USAF) missile base in Wyoming, when the administrations of four Philippine and four United States presidents could not. On December 14, 2018, the “Bells of Balangiga” returned to the Church of San Lorenzo de Martir on the island of Samar in the Philippines. For over 100 years they were on a military base near Cheyenne, Wyoming; first U.S. Army Fort D.A. Russell, a cavalry post and home of three regiments of the famous African-American “Buffalo Soldiers,” then renamed Francis E. Warren U. S. Air Force Base (AFB), home of the ICBM Minuteman III 90th Missile Wing and Twentieth Air Force. In 1904 two 600-pound church bells were brought to Wyoming by the U.S. Army 11th Infantry Regi- ment as souvenirs from the “Philippine Insurrection,” now officially the “Philippine-American War.” They were originally believed used to signal a September 1901 Saturday morning surprise attack by Philippine revolutionaries against Company C, 9th Infantry Regiment. -

Brown Man's Burden: a Commentary

1 Brown Man's Burden: A Commentary By Bea C. Rodriguez "The masses of the Filipino people have yet to learn the lessons of political honesty, of thrift and of self-reliance; they have yet to learn that political office is a public trust. Possibly the United States is not the best teacher of this lesson; it must be learned none the less. They have yet to learn that mutual concession, the graceful yielding of the minority to the will of the majority and respect for the rights of others are essentials of successful democracy. Not until they have developed these homely civic virtues can they expect to have an efficient self-government." —E. W. Kemmerer, 1908 In July 2017, Philippine President Duterte asked for the United States to return the Balangiga bells to the Filipino people. Since the 1990s, the Philippine government has asked for what's rightfully theirs; but the US has repeatedly refused. The Clinton administration insisted that the bells were the property of the American government. Not losing hope, the former American colony continued to ask for the bells in 2002 and 2004. Alas, nothing happened. Finally, in 2006, three American lawmakers—Bob Filner, Dana Rohracher and Ed Case—urged President Bush to authorize the return of the bells. Again, nothing happened. In January 2018, two American lawmakers objected to Duterte's recent request, expressing their "deepest concerns with the human rights record" by Duterte's Philippine Drug War. In a letter, Representatives Randy Hultgren and Jim McGovern asked US Defense Secretary Jim Mattis not to provide certification for the return of the bells until the Philippine government puts an end to the extrajudicial killings. -

The Bells of Balangiga: a Tale of Missed Opportunity

The Bells of Balangiga: A Tale of Missed Opportunity Carole Butcher North Dakota State University Department of History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies 4727 Arbor Crossing #324 Alexandria, MN 56308 218-731-5672 [email protected] 1 The Bells of Balangiga: A Tale of Missed Opportunity Carole Butcher The Philippine-American War broke out in 1899 hard on the heels of the Spanish American War. Although the conflict began as conventional warfare, American troops unexpectedly found themselves engaged in a guerilla war. This article examines one small incident that occurred on the island of Samar. It demonstrates how American soldiers completely misread a situation that resulted in a massacre that was the American Army’s worst defeat since Custer’s demise in 1876. KEY WORDS: Philippine-American War; United States Army; Philippines; Balangiga; Samar; Leyte Gulf; massacre; guerilla war; insurgency; insurrection In October, 1897, a major typhoon struck the Leyte Gulf. The storm had a terrible impact on the Philippines. Father Jose Algue of the Observatorio de Manila described the ‘montaña o masa de agua’ (the mountain or mass of water) and reported that Samar and Leyte bore the brunt of the storm.1 As a result of the typhoon, fishermen and farmers lost their livelihoods. Virtually all provisions that had been stored were destroyed. The Barrier Miner, a newspaper from Broken Hill, New South Wales, reported that an estimated 7,000 people were killed. Numerous ships were wrecked and the crews were lost.2 The few photographs that exist of the aftermath clearly show vast areas wiped clean of trees, houses, churches, and crops. -

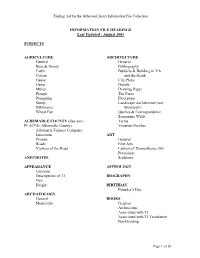

INFORMATION FILE HEADINGS Last Updated : August 2003

Finding Aid for the Jefferson Library Information File Collection INFORMATION FILE HEADINGS Last Updated : August 2003 SUBJECTS AGRICULTURE ARCHITECTURE General General Bees & Honey Bibliography Cattle Builders & Building in VA Cotton and the South Geese City Plans Hemp Details Mules Drawing Paper Plough The Farm Ploughing Floorplans Sheep Landscape Architecture (not Silkworms Monticello Wheat Fan Queries & Correspondence Serpentine Walls ALBEMARLE COUNTY (See also: Terms PLACES--Albemarle County) Venetian Porches Albemarle Furnace Company Limestone ART Prisons General Roads Fine Arts Viewers of the Road Lantern of Demosthenes (M) Portraiture ANECDOTES Sculpture APPEARANCE ASTROLOGY Cartoons Descriptions of TJ BIOGRAPHY Hair Height BIRTHDAY Founder’s Day ARCHAEOLOGY General BOOKS Monticello General Architecture Associated with TJ Associated with TJ Translation Bookbinding Page 1 of 20 Finding Aid for the Jefferson Library Information File Collection BOOKS (CONT’D) CONSTITUTION (See: POLITICAL Book Dealers LIFE--Constitution) Book Marks Book Shelves CUSTOMS Catalogs Goose Night Children’s Reading Classics DEATH Common Place Epitaphs Dictionaries Funeral Encyclopedias Last Words Ivory Books Law Books EDUCATION Library of Congress General Notes on the State of Virginia Foreign Languages Poplar Forest Reference Bibliographies ENLIGHTENMENT Restored Library Retirement Library FAMILY Reviews of Books Related to TJ Coat of Arms Sale of 1815 Seal Skipwith Letter TJ Copies Surviving FAMILY LIFE Children CALENDAR Christmas Marriage CANALS The "Monticello -

The Ball Was a Blast! for the First Time As the Barker Detachment, the Membership Gathered Together to Celebrate the 241St Year of Our Beloved Corps

Preserving and Promoting the Time Honored Traditions Of Our Beloved Marine Corps Now and Forever! Semper Fidelis dec The Ball Was a Blast! For the first time as the Barker Detachment, the membership gathered together to celebrate the 241st year of our beloved Corps. The evening started out with a great cocktail hour where everyone mingled and had a great time. At the sound of the bugle, the ceremonies began. The Detachment membership along with guests from West Hudson and other organizations as well as two active warriors from the Corps and the Navy marched in! Commandant Poole then escorted the Guest of Honor Col. Bill Murray forward and the Honor Guard presented the LCPL Burns and PFC (Then Pvt) Colors. Following the National Anthem the Colors were Gavin Escort the cake posted and the cake was brought forward. Col. Murray 2016 received the first piece of cake. Bobby Re then received the second piece as the oldest Marine present. He then passed to Warriors the youngest Marine LCpl John Burns. The Commandants’ messages were read and the Missing Man Table was contributing to presented. We all enjoyed some great chow, fine music and Scoopthis issue dancing. The Commandant then presented the annual awards and the Marine of the Year Committee then bestowed the title Tim Daudelin of Marine of the Year on Ed Ebel. Carlos Poole Video presentations, more music and great times continued Dan Hoffmann on until the end of the evening. A great evening of camaraderie and fun, and we cant wait until 8 November 2017 Commandant Poole with Albert Paul GOH Col. -

Download/Csipubs/Modernwarfare.Pdf

DOING WHAT YOU KNOW THE UNITED STATES AND 250 YEARS OF IRREGULAR WAR DAVID E. JOHNSON DOING WHAT YOU KNOW THE UNITED STATES AND 250 YEARS OF IRREGULAR WARFARE DAVID E. JOHNSON 2017 ABOUT THE CENTER FOR STRATEGIC AND BUDGETARY ASSESSMENTS (CSBA) The Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments is an independent, nonpartisan policy research institute established to promote innovative thinking and debate about national security strategy and investment options. CSBA’s analysis focuses on key questions related to existing and emerging threats to U.S. national security, and its goal is to enable policymakers to make informed decisions on matters of strategy, security policy, and resource allocation. ©2017 Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments. All rights reserved. ABOUT THE AUTHOR David E. Johnson is a Senior Fellow at CSBA. He joined CSBA after eighteen years with the RAND Corporation, where he was a Principal Researcher. His work focuses on military innovation, land warfare, joint operations, and strategy. Dr. Johnson is also an adjunct professor at Georgetown University where he teaches a course on strategy and military operations and an Adjunct Scholar at the Modern War Institute at West Point. From June 2012 until July 2014, he was on a two-year loan to the United States Army to establish and serve as the first director of the Chief of Staff of the Army Strategic Studies Group. Before joining RAND, he served as a vice president at Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) following a 24-year career in the U.S. Army, where he served in command and staff positions in the Infantry, Quartermaster Corps, and Field Artillery branches in the continental United States, Korea, Germany, Hawaii, and Belgium. -

Virginia's Civil

Virginia’s Civil War A Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A A., Jim, Letters, 1864. 2 items. Photocopies. Mss2A1b. This collection contains photocopies of two letters home from a member of the 30th Virginia Infantry Regiment. The first letter, 11 April 1864, concerns camp life near Kinston, N.C., and an impending advance of a Confederate ironclad on the Neuse River against New Bern, N.C. The second letter, 11 June 1864, includes family news, a description of life in the trenches on Turkey Hill in Henrico County during the battle of Cold Harbor, and speculation on Ulysses S. Grant's strategy. The collection includes typescript copies of both letters. Aaron, David, Letter, 1864. 1 item. Mss2AA753a1. A letter, 10 November 1864, from David Aaron to Dr. Thomas H. Williams of the Confederate Medical Department concerning Durant da Ponte, a reporter from the Richmond Whig, and medical supplies received by the CSS Stonewall. Albright, James W., Diary, 1862–1865. 1 item. Printed copy. Mss5:1AL155:1. Kept by James W. Albright of the 12th Virginia Artillery Battalion, this diary, 26 June 1862–9 April 1865, contains entries concerning the unit's service in the Seven Days' battles, the Suffolk and Petersburg campaigns, and the Appomattox campaign. The diary was printed in the Asheville Gazette News, 29 August 1908. Alexander, Thomas R., Account Book, 1848–1887. 1 volume. Mss5:3AL276:1. Kept by Thomas R. Alexander (d. 1866?), a Prince William County merchant, this account book, 1848–1887, contains a list, 1862, of merchandise confiscated by an unidentified Union cavalry regiment and the 49th New York Infantry Regiment of the Army of the Potomac.