1 Reevaluating the Nanjing Decade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chinese Civil War (1927–37 and 1946–49)

13 CIVIL WAR CASE STUDY 2: THE CHINESE CIVIL WAR (1927–37 AND 1946–49) As you read this chapter you need to focus on the following essay questions: • Analyze the causes of the Chinese Civil War. • To what extent was the communist victory in China due to the use of guerrilla warfare? • In what ways was the Chinese Civil War a revolutionary war? For the first half of the 20th century, China faced political chaos. Following a revolution in 1911, which overthrew the Manchu dynasty, the new Republic failed to take hold and China continued to be exploited by foreign powers, lacking any strong central government. The Chinese Civil War was an attempt by two ideologically opposed forces – the nationalists and the communists – to see who would ultimately be able to restore order and regain central control over China. The struggle between these two forces, which officially started in 1927, was interrupted by the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937, but started again in 1946 once the war with Japan was over. The results of this war were to have a major effect not just on China itself, but also on the international stage. Mao Zedong, the communist Timeline of events – 1911–27 victor of the Chinese Civil War. 1911 Double Tenth Revolution and establishment of the Chinese Republic 1912 Dr Sun Yixian becomes Provisional President of the Republic. Guomindang (GMD) formed and wins majority in parliament. Sun resigns and Yuan Shikai declared provisional president 1915 Japan’s Twenty-One Demands. Yuan attempts to become Emperor 1916 Yuan dies/warlord era begins 1917 Sun attempts to set up republic in Guangzhou. -

February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation Between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified February 04, 1949 Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong Citation: “Memorandum of Conversation between Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong,” February 04, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, APRF: F. 39, Op. 1, D. 39, Ll. 54-62. Reprinted in Andrei Ledovskii, Raisa Mirovitskaia and Vladimir Miasnikov, Sovetsko-Kitaiskie Otnosheniia, Vol. 5, Book 2, 1946-February 1950 (Moscow: Pamiatniki Istoricheskoi Mysli, 2005), pp. 66-72. Translated by Sergey Radchenko. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/113318 Summary: Anastas Mikoyan and Mao Zedong discuss the independence of Mongolia, the independence movement in Xinjiang, the construction of a railroad in Xinjiang, CCP contacts with the VKP(b), the candidate for Chinese ambassador to the USSR, aid from the USSR to China, CCP negotiations with the Guomindang, the preparatory commisssion for convening the PCM, the character of future rule in China, Chinese treaties with foreign powers, and the Sino-Soviet treaty. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation On 4 February 1949 another meeting with Mao Zedong took place in the presence of CCP CC Politburo members Zhou Enlai, Liu Shaoqi, Ren Bishi, Zhu De and the interpreter Shi Zhe. From our side Kovalev I[van]. V. and Kovalev E.F. were present. THE NATIONAL QUESTION I conveyed to Mao Zedong that our CC does not advise the Chinese Com[munist] Party to go overboard in the national question by means of providing independence to national minorities and thereby reducing the territory of the Chinese state in connection with the communists' take-over of power. -

Guangdong-Guangxi War & Sun Yat-Sen's Return to Canton

Sun Yat-sen's Return To Canton After Expelling Gui-xi by Ah Xiang Excerpts from “Tragedy of Chinese Revolution” at http://www.republicanchina.org/revolution.html For updates and related articles, check http://www.republicanchina.org/RepublicanChina-pdf.htm In Southern Chinese Province of Guangdong, Sun Yat-sen and Chen Jiongming would be entangled in the power struggles. (Liu Xiaobo mistakenly eulogized Chen Jiongming's support for so-called "allying multiple provinces for self-determination" as heralding China's forerunner federationist movement.) Yue-jun (i.e., Guangdong native army), headed by Chen Jiongming, was organized on basis of Zhu Qinglan's police/guard battalions in Dec of 1917. To make Chen Jiongming into a real military support, Sun Yat-sen originally dispatched Hu Hanmin and Wang Zhaoming to Governor Zhu Qinglan for making Chen Jiongming into the so-called "commander of governor's bodyguard column". Governor Zhu Qinglan was forced into resignation by Governor-general Chen Bingkun of Gui-xi faction (i.e., Guangxi Province native army that stationed in Guangdong after the republic restoration war). Sun Yat-sen asked Cheng Biguang negotiate with Lu Rongding for relocation of Chen Bingkun and assignment of twenty battalions of Zhu Qinglan's police/guard army into 'marines' under the command of Cheng Biguang's navy. On Dec 2nd of 1917, Chen Jiongming was conferred the post of "commander of Guangdong army for aiding Fujian Province" and was ordered to lead 4000-5000 'marine' army towards neighboring Fujian Province where he expanded his army and developed it into his private warlord or militarist forces. -

© 2013 Yi-Ling Lin

© 2013 Yi-ling Lin CULTURAL ENGAGEMENT IN MISSIONARY CHINA: AMERICAN MISSIONARY NOVELS 1880-1930 BY YI-LING LIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral committee: Professor Waïl S. Hassan, Chair Professor Emeritus Leon Chai, Director of Research Professor Emeritus Michael Palencia-Roth Associate Professor Robert Tierney Associate Professor Gar y G. Xu Associate Professor Rania Huntington, University of Wisconsin at Madison Abstract From a comparative standpoint, the American Protestant missionary enterprise in China was built on a paradox in cross-cultural encounters. In order to convert the Chinese—whose religion they rejected—American missionaries adopted strategies of assimilation (e.g. learning Chinese and associating with the Chinese) to facilitate their work. My dissertation explores how American Protestant missionaries negotiated the rejection-assimilation paradox involved in their missionary work and forged a cultural identification with China in their English novels set in China between the late Qing and 1930. I argue that the missionaries’ novelistic expression of that identification was influenced by many factors: their targeted audience, their motives, their work, and their perceptions of the missionary enterprise, cultural difference, and their own missionary identity. Hence, missionary novels may not necessarily be about conversion, the missionaries’ primary objective but one that suggests their resistance to Chinese culture, or at least its religion. Instead, the missionary novels I study culminate in a non-conversion theme that problematizes the possibility of cultural assimilation and identification over ineradicable racial and cultural differences. -

002170196E1c16a28b910f.Pdf

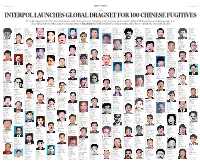

6 THURSDAY, APRIL 23, 2015 DOCUMENT CHINA DAILY 7 JUSTICE INTERPOL LAUNCHES GLOBAL DRAGNET FOR 100 CHINESE FUGITIVES It’s called Operation Sky Net. Amid the nation’s intensifying antigraft campaign, arrest warrants were issued by Interpol China for former State employees and others suspected of a wide range of corrupt practices. China Daily was authorized by the Chinese justice authorities to publish the information below. Language spoken: Liu Xu Charges: Place of birth: Anhui property and goods Language spoken: Zeng Ziheng He Jian Qiu Gengmin Wang Qingwei Wang Linjuan Chinese, English Sex: Male Embezzlement Language spoken: of another party by Chinese Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Male Sex: Female Charges: Date of birth: Chinese, English fraud Charges: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Date of birth: Accepting bribes 07/02/1984 Charges: Embezzlement Embezzlement 15/07/1971 14/11/1965 15/05/1962 03/01/1972 17/07/1980 Place of birth: Beijing Place of birth: Henan Language spoken: Place of birth: Place of birth: Place of birth: Language spoken: Language spoken: Chinese Zhejiang Jinan, Shandong Jilin Chinese, English Chinese Charges: Graft Language spoken: Language spoken: Language spoken: Charges: Corruption Charges: Chinese Chinese, English Chinese Embezzlement Charges: Contract Charges: Commits Charges: fraud, and flight of fraud by means of a Misappropriation of Yang Xiuzhu 25/11/1945 Place of birth: Chinese Zhang Liping capital contribution Chu Shilin letter of credit Dai Xuemin public funds Sex: Female -

Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2019 Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927 Ryan C. Ferro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Scholar Commons Citation Ferro, Ryan C., "Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist Guomindang Split of 1927" (2019). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nationalism and the Communists: Re-Evaluating the Communist-Guomindang Split of 1927 by Ryan C. Ferro A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-MaJor Professor: Golfo Alexopoulos, Ph.D. Co-MaJor Professor: Kees Boterbloem, Ph.D. Iwa Nawrocki, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2019 Keywords: United Front, Modern China, Revolution, Mao, Jiang Copyright © 2019, Ryan C. Ferro i Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….…...ii Chapter One: Introduction…..…………...………………………………………………...……...1 1920s China-Historiographical Overview………………………………………...………5 China’s Long -

Second Northern Expedition 1928: Part II V.1.0 March 7, 2007

Second Northern Expedition 1928: Part II v.1.0 March 7, 2007 An Xiang With permission from the author, whose page “China’s Wars” appears in www.orbat.com [See History]. Formatted by Ravi Rikhye. Editor’s Note The blue area is under direct KMT rule. Pink is under major warlord coalitions. White is under minor warlords. A larger version of this map is available at http://www.dean.usma.edu/history/web03/atlases/ chinese%20civil%20war/chinese%20civil%20war%20index.htm The background to the campaign is that following the deposing of the Chinese Qing Dynasty in 1912, China became a republic and a series of civil wars began. He formed the National Revolutionary Army in 1925. His political part, the Kuomintang, and the NRA operated under the guidance of and with material assistance from the Soviet Comintern. The NRA included the Communists, who formed the 4th and 8th Route Armies of the NRA, and both factions cooperated in the Northern Expedition of 1926-27. The Expedition started from the KMT’s power base in Guangdong with a push north against 3 main warlords. In 1927 Chiang purged the Communists from his alliance. In 1928 he launched the Second Northern Expedition. This culminated in the capture of Beijing and the supremacy of the KMT. Chiang next turned his attention to fighting the Communists. The situation was very complex because of the arrival of the Japanese. The 3-way struggle became a war between the KMT and the Communists when Japan was defeated in 1945, and culminated in the Communist victory of 1949. -

General He Yingqin: the Rise and Fall of Nationalist China. <I>By Peter Worthing</I>

Pacific Affairs: Volume 90, No. 3 – September 2017 The chapters that frame this volume make clear the different approaches that China and the United States have towards energy security. Ideologically, US and Chinese pursuit of energy security reflect radically differing embedded assumptions. As the authors note, while the US has long advocated markets over mercantilism and institutions that help avoid zero-sum approaches in crisis, China has emphasized securing external supply and developing long- term state-to-state relationships. The cases presented here suggest that the US has not used energy to constrain China’s rise, but neither has it focused on safeguarding the US market vision for energy. This volume strongly illustrates China’s long-term commitment to ensuring its access to adequate energy for the future. Meanwhile, the United States, through the development of its resources at home (and radical shifts in price), has become less engaged in energy development and in the concerns of resource-rich states. How China’s participation will change markets and relations in the long term remains to be seen, but this volume offers rare insight into how China’s participation is progressing to date. National War College/National Defense University Theresa Sabonis-Helf Washington, DC, USA *Views expressed in this review are solely the author’s and do not represent the official position of the US Government, Department of Defense, or the National Defense University. GENERAL HE YINGQIN: The Rise and Fall of Nationalist China. By Peter Worthing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. viii, 316 pp. (Maps.) US$99.99, cloth. ISBN 978-1-107-14463-7. -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Across the Geo-political Landscape Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political Networks in the Wartime Era 1937-1949 Guo, Xiangwei Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Across the Geo-political Landscape: Chinese Women Intellectuals’ Political -

Citizenship and Government in Transition in Nationalist China, 1927±1937Ã

IRSH 46 (2001), Supplement, pp. 185±207 DOI: 10.1017/S0020859001000372 # 2001 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis ``Begging the Sages of the Party-State'': Citizenship and Government in Transition in Nationalist China, 1927±1937à Rebecca Nedostup and Liang Hong-ming The premise of the Nationalist government at Nanjing (1927±1937) rested on a precarious balance of democracy and paternalism. The Nationalists drew their power from China's citizens, but they also subjected them to a regimen of training and control. Petitions from the ``Nanjing decade'' highlight the resulting tensions between government and the governed. Citizens from all walks of life accepted the ruling party's invitation to participate in the construction of the republic. Yet they also used petitions to seek redress when they believed the Nationalists had fallen short of their obligations. These documents mark a turbulent period of transition from imperial rule to representative democracy. They also characterize an era when new political ideas, new media, and new social organizations helped people take an old device and transform it into a useful weapon for asserting their rights as modern citizens. TUTELARY GOVERNMENT AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE MODERN PETITION The ®nal Chinese dynasty had been overthrown in 1911 because it was unresponsive to the changing opinions of its subjects. The imperial government had maintained a tradition of court memorials circulated between local and higher of®cials, all the way up to the Emperor.1 But this à The materials used in this article were gathered with support from the Center for Chinese Studies (Taipei, Taiwan), the Fulbright Foundation, the Chiang-Ching Kuo Foundation, the Committee on Scholarly Communication with China, and the American Council of Learned Societies. -

Part II Chapter 1 How China Became a Communist Country

Page 64 Part II Chapter 1 How China Became a Communist Country s we have seen the containment doctrine worked well in western Europe. Indeed, after 1945, the Soviet Union did not take over any country where it did not already have troops. Soviet attempts Ato detach Berlin from the West, to infiltrate into Greece, to capture control of Italy and France through communist party victories at the polls, all failed. The Marshall Plan put Europe back on its feet economically; the Truman Doctrine gave Greece and Turkey the help they needed to resist Soviet advances; the airlift saved Berlin; and NATO provided a guarantee of American military aid if needed. Americans had good reasons to be proud of their successes in this vitally important area of the globe. Unfortunately, success among the relatively established industrialized states of Europe could not be duplicated in the shifting, agricultural societies of Asia. Here, and most particularly in China, Americans were confronted with a far more complex situation than in Europe -and it is to this part of the globe that our attention now must turn. Forty Years of Revolution in China There is an old saying known to people who knew Chinese history and culture that no revolution could succeed there without the support of its scholars and its peasants. Unfortunately, most Americans who evaluated policy decisions about China knew little about either its history or its culture. Chinese civilization has a recorded history of some 4,000 years. These can be divided into a series of dynasties or empires, one following another as internal collapse was triggered by strong pressure from the outside. -

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing

Modernism in Practice: Shi Zhecun's Psychoanalytic Fiction Writing Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Zhu, Yingyue Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 14:07:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/642043 MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING by Yingyue Zhu ____________________________ Copyright © Yingyue Zhu 2020 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2020 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Master’s Committee, we certify that we have read the thesis prepared by Yingyue Zhu, titled MODERNISM IN PRACTICE: SHI ZHECUN’S PSYCHOANALYTIC FICTION WRITING and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Master’s Degree. Jun 29, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Dian Li Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Fabio Lanza Jul 2, 2020 _________________________________________________________________ Date: ____________ Scott Gregory Final approval and acceptance of this thesis is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the thesis to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this thesis prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the Master’s requirement.