Martial Arts (An Introduction To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Behind the Mask: My Autobiography

Contents 1. List of Illustrations 2. Prologue 3. Introduction 4. 1 King for a Day 5. 2 Destiny’s Child 6. 3 Paris 7. 4 Vested Interests 8. 5 School of Hard Knocks 9. 6 Rolling with the Punches 10. 7 Finding Klitschko 11. 8 The Dark 12. 9 Into the Light 13. 10 Fat Chance 14. 11 Wild Ambition 15. 12 Drawing Power 16. 13 Family Values 17. 14 A New Dawn 18. 15 Bigger than Boxing 19. Illustrations 20. Useful Mental Health Contacts 21. Professional Boxing Record 22. Index About the Author Tyson Fury is the undefeated lineal heavyweight champion of the world. Born and raised in Manchester, Fury weighed just 1lb at birth after being born three months premature. His father John named him after Mike Tyson. From Irish traveller heritage, the“Gypsy King” is undefeated in 28 professional fights, winning 27 with 19 knockouts, and drawing once. His most famous victory came in 2015, when he stunned longtime champion Wladimir Klitschko to win the WBA, IBF and WBO world heavyweight titles. He was forced to vacate the belts because of issues with drugs, alcohol and mental health, and did not fight again for more than two years. Most thought he was done with boxing forever. Until an amazing comeback fight with Deontay Wilder in December 2018. It was an instant classic, ending in a split decision tie. Outside of the ring, Tyson Fury is a mental health ambassador. He donated his million dollar purse from the Deontay Wilder fight to the homeless. This book is dedicated to the cause of mental health awareness. -

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema

Fighters and Fathers: Managing Masculinity in Contemporary Boxing Cinema JOSH SOPIARZ In Antoine Fuqua’s film Southpaw (2015), just as Jake Gyllenhaal’s character Billy Hope attempts suicide by crashing his luxury sedan into a tree in the front yard, his ten-year-old daughter, Leila, sends him a text message asking: “Daddy. Where are you?” (00:46:04). Her answer comes seconds later when, upon hearing a crash, she finds her father in a heap concussed and bleeding badly on the white marble floor of their home’s entryway. Upon waking, Billy’s first and only concern is Leila. Hospital workers, in an effort to calm him, tell Billy that Leila is safe “with child services” (00:48:08-00:48:10) This news does not comfort Billy. Instead, upon learning that Leila is in the state’s custody, the former light heavyweight champion of the world, with face bloodied and muscles rippling, makes his most concerted effort to get up and leave—presumably, to find his daughter. Before he can rise, however, a doctor administers a large dose of sedative and the heretofore unrestrainable Billy fades into unconsciousness as the scene ends. Leila’s simple question—“Daddy. Where are you?”—is central not only to Southpaw but is also relevant for most major boxing films of the 21st century.1 This includes Clint Eastwood’s Million Dollar Baby (2004), David O. Russell’s The Fighter (2010), Ryan Coogler’s Creed (2015), Jonathan Jakubowic’s Hands of Stone (2016), and Stephen Caple, Jr.’s Creed II (2018). These films establish fighter/trainer relationships as alternatives to otherwise biological or “traditional” father/son relationships. -

South African Combat Sports Bill, 2009

1 SOUTH AFRICAN COMBAT SPORTS BILL, 2009 To provide for the regulation, control and general supervision of combat sports in the Republic; to ensure the effective and efficient administration of combat sports in the Republic; to recognise amateur combat sports; to create synergy between professional and amateur combat sports to ensure the effective and efficient administration of combat sports in the Republic;; and to provide for matters connected therewith. BE IT ENACTED by the Parliament of the Republic of South Africa, as follows— Definitions 1. In this Act, unless the context indicates otherwise— “amateur combat sports” means any form of combat sports without a pecuniary incentive for a participant in combat sports; “contact sport” means a sport where the rules of a sport allow for significant physical contact between its participants; “combat sports” means a competitive contact sport where two combatants fight against each other using certain rules of engagement, typically with the aim of simulating parts of real hand to hand combat involving techniques which encompass strikes, kicks, elbows and knees, grappling, superior positions, throws, both striking and grappling, hybrid martial arts and weaponry; “controlling body” means - (a) a national federation as defined in section 1 of the National Sport and Recreation Act, 1998 (Act No. 110 of 1998); South African Combat Bill 2 (b) a provincial federation; (c) an international controlling body; or (d) an other body governing a code of combat sports in the Republic under whose auspices a specific combat sports as indicated in the definition of “combat sports” fall; “elbow” means a strike with the point of the elbow, the part of the forearm nearest to the elbow, or the part of the upper arm nearest to the elbow and can be thrown sideways similarly to a hook, upwards similarly to an uppercut, or downwards with the point of the elbow. -

An Analytical Study on Wrestling in India

International Journal of Enhanced Research in Educational Development (IJERED), ISSN: 2320-8708 Vol. 2, Issue 5, Sept.-Oct., 2014, pp: (10-15), Impact Factor: 1.125, Available online at: www.erpublications.com An analytical study on Wrestling in India Rekha Narwal MKJK College, MDU Rohtak, Haryana, India Abstract: This manuscript gives an analytical study on Wrestling in India. In preparing young wrestlers (16-17 years of age) the design often follows a relatively well-developed system of training for adult masters of sport. In general, the youthful body is characterized by a high intensity cardio-respiratory and blood systems during physical stress. So far, no data on the impact of intense competitive activity on the dynamics of individual aspects of preparedness of young wrestlers is available. Our objective was to study the impact of competitive activity on the functional training state in young wrestlers. Keywords: Competitions, Rules, Female Wrestling, Factor Analysis, Technique Wrestlers, training, weight management. INTRODUCTION Wrestling is unique among athletics. It is considered to be one of the most physically demanding sports among high school and college athletics. Wrestling was one of the most favored events in the Olympic Games in Ancient Greece. The first organized national wrestling tournament took place in New York City in 1888. From the Athens Games in 1896, until today, the wrestling events are also an important part of the modern Olympic Games. The International Federation of Associated Wrestling Styles (FILA) originated in 1912 in Antwerp, Belgium. The 1st NCAA Wrestling Championships were also held in 1912, in Ames, Iowa. USA Wrestling, located in Colorado Springs, Colorado, became the national governing body of amateur wrestling in 1983. -

Gary Russell, Patrick Hyland, Jose Pedraza, Stephen Smith

APRIL 16 TRAINING CAMP NOTES: GARY RUSSELL, PATRICK HYLAND, JOSE PEDRAZA, STEPHEN SMITH NEW YORK (April 7, 2016) – The boxers who will be fighting Saturday, April 16 on a SHOWTIME CHAMPIONSHIP BOXING® world title doubleheader are deep into their respective training camps as they continue preparation for their bouts at Foxwoods Resort Casino in Mashantucket, CT. In the main event, live on SHOWTIME® (11 p.m. ET/8 p.m. PT), the talented and speedy southpaw Gary Russell Jr. (26-1, 15 KOs) makes the first defense of his WBC Featherweight World Title against Irish contender Patrick Hyland (31-1, 15 KOs). In the SHOWTIME co-feature, unbeaten sniper Jose Pedraza (21-0, 12 KOs) risks his IBF 130-pound world title as he defends his title for the second time against a mandatory challenger, Stephen Smith (23-1, 13 KOs). Russell, who won the 126-pound title with a fourth-round knockout over defending champion Jhonny Gonzalez on March 28, 2015, trains in Washington, D.C. Hyland, whose only loss suffered was to WBA Super Featherweight World Champion Javier Fortuna, has been training at a gym in Dublin, Ireland, owned and operated by his trainer, Paschal Collins, whose older brother Steve was a former two-time WBO world champion. Paschal Collins also boxed as a pro but is best known for being Irish heavyweight Kevin McBride’s head trainer during his shocking knockout of Mike Tyson. The switch-hitting Pedraza, a 2012 Puerto Rican Olympian, has been working out in his native Puerto Rico. Smith, of Liverpool, England, has been training in the UK. -

Name: Wally Thom Born: 1926-06-14 Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Birkenhead, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: Click

1 Name: Wally Thom Born: 1926-06-14 Nationality: United Kingdom Hometown: Birkenhead, Merseyside, United Kingdom Boxing Record: click The digger you dig into the ring record of Birkenhead Wally Thom the more impressive becomes the fight career of a man who must rank very high on the list of Merseyside’s all time boxing greats. As an amateur he was a junior ABA finalist on two occasions, a senior ABA finalist, was to box internationally against Denmark, reaching the finals of the European Championships in Dublin, and also won a Welsh title. As a professional boxer he suffered greatly from cuts around his eyes in the later stages of his career yet he met and beat some of the top fighters in the world. He reigned as the British and Empire welterweight champion and in a professional career lasting from 1949 to 1956 he won 42 of his 54 contests, with 11 defeats – mostly due to cuts -, and one draw. He was one of the most effective southpaws of all time, yet if the old Birkenhead club trainer Tommy Murray would have had his way Wally would have been an orthodox boxer. Wally’s interest in boxing was stirred by his father who bought him a speed ball from a sports shop in Grange road Birkenhead. “ I had great fun with it but had not thought of taking up boxing until one day at school – Tollemache road , Birkenhead – a teacher called for volunteers to represent the school in the Birkenhead boys championship for the Blake cup. I had a go and won through to the event at Byrne Avenue Swimming Baths, Birkenhead, only to be declared half a stone under the weight required”. -

The Southpaw Advantage? - Lateral Preference in Mixed Martial Arts

The Southpaw Advantage? - Lateral Preference in Mixed Martial Arts Joseph Baker1*,Jo¨ rg Schorer2 1 School of Kinesiology and Health Science, York University, Toronto, Canada, 2 Institute of Sport Science, University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany Abstract Performers with a left-orientation have a greater likelihood of obtaining elite levels of performance in many interactive sports. This study examined whether combat stance orientation was related to skill and success in Mixed Martial Arts fighters. Data were extracted for 1468 mixed martial artists from a reliable and valid online data source. Measures included fighting stance, win percentage and an ordinal measure of skill based on number of fights. The overall analysis revealed that the fraction of fighters using a southpaw stance was greater than the fraction of left-handers in the general population, but the relationship between stance and hand-preference is not well-understood. Furthermore, t-tests found no statistically significant relationship between laterality and winning percentage, although there was a significant difference between stances for number of fights. Southpaw fighters had a greater number of fights than those using an orthodox stance. These results contribute to an expanding database on the influence of laterality on sport performance and a relatively limited database on variables associated with success in mixed martial arts. Citation: Baker J, Schorer J (2013) The Southpaw Advantage? - Lateral Preference in Mixed Martial Arts. PLoS ONE 8(11): e79793. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0079793 Editor: Robert J. van Beers, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands Received March 26, 2013; Accepted September 25, 2013; Published November 19, 2013 Copyright: ß 2013 Baker, Schorer. -

Mixed Martial Arts

COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 Mixed Martial Arts - Overview Mixed Martial Arts is an action-packed sport filled with striking and grappling techniques from a variety of combat sports and martial arts. During the early 1900s, many different mixed-style competitions were held throughout Europe, Japan and the Pacific Rim. CV Productions Inc. showed the first regulated MMA league in the US in 1980 called the Tough Guy Contest, which was later renamed as Battle of the Superfighters. In 1983, the Pennsylvania State Senate passed a bill which prohibited the sport. However, in 1993, it was brought back into the US TVs by the Gracie family who found the Ultimate Fighting Championships (UFC) which most of us have probably heard about on our TVs. These shows were promoted as a competition which intended in finding the most effective martial arts in an unarmed combat situation. The competitors fought each other with only a few rules controlling the fight. Later on, additional rules were established ensuring a little more safety for the competitors, although it still is quite life-threatening. A Brief History of Mixed Martial Arts THANKS FOR READING – VISIT OUR WEBSITE www.educatererindia.com COMPILED BY : - GAUTAM SINGH STUDY MATERIAL – SPORTS 0 7830294949 The history of MMA dates back to the Greek era. There was an ancient Olympic combat sport called as Pankration which had features of combination of grappling and striking skills. Later, this sport was passed on to the Romans. An early example of MMA is Greco-Roman Wrestling (GRW) in the late 1880s, where players fought without few to almost zero safety rules. -

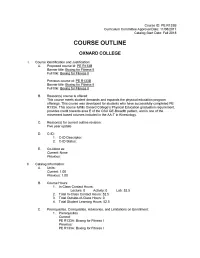

Oxnard Course Outline

Course ID: PE R133B Curriculum Committee Approval Date: 11/08/2017 Catalog Start Date: Fall 2018 COURSE OUTLINE OXNARD COLLEGE I. Course Identification and Justification: A. Proposed course id: PE R133B Banner title: Boxing for Fitness II Full title: Boxing for Fitness II Previous course id: PE R133B Banner title: Boxing for Fitness II Full title: Boxing for Fitness II B. Reason(s) course is offered: This course meets student demands and expands the physical education program offerings. This course was developed for students who have successfully completed PE R133A. This course fulfills Oxnard College’s Physical Education graduation requirement, provides credit towards area E of the CSU GE-Breadth pattern, and is one of the movement based courses included in the AA-T in Kinesiology. C. Reason(s) for current outline revision: Five year update D. C-ID: 1. C-ID Descriptor: 2. C-ID Status: E. Co-listed as: Current: None Previous: II. Catalog Information: A. Units: Current: 1.00 Previous: 1.00 B. Course Hours: 1. In-Class Contact Hours: Lecture: 0 Activity: 0 Lab: 52.5 2. Total In-Class Contact Hours: 52.5 3. Total Outside-of-Class Hours: 0 4. Total Student Learning Hours: 52.5 C. Prerequisites, Corequisites, Advisories, and Limitations on Enrollment: 1. Prerequisites Current: PE R133A: Boxing for Fitness I Previous: PE R133A: Boxing for Fitness I 2. Corequisites Current: Previous: 3. Advisories: Current: Previous: 4. Limitations on Enrollment: Current: Previous: D. Catalog description: Current: This course is designed to increase cardiorespiratory conditioning and fitness through the use of intermediate boxing techniques. -

Our Exclusive Rankings

#1 #10 #53 #14 #9 THE BIBLE OF BOXING + OUR EXCLUSIVE + RANKINGS P.40 + + ® #3 #13 #12 #26 #11 #8 #29 SO LONG CANELO BEST I TO A GEM s HBO FACED DAN GOOSSEN WHAT ALVAREZ’S HALL OF FAMER MADE THE BUSINESS ROBERTO DURAN JANUARY 2015 JANUARY MOVE MEANS FOR MORE FUN P.66 THE FUTURE P.70 REVEALS HIS TOP $8.95 OPPONENTS P.20 JANUARY 2015 70 What will be the impact of Canelo Alvarez’s decision to jump from FEATURES Showtime to HBO? 40 RING 100 76 TO THE POINT #1 #10 #53 #14 #9 THE BIBLE OF BOXING + OUR OUR ANNUAL RANKING OF THE REFS MUST BE JUDICIOUS WHEN EXCLUSIVE + RANKINGS P.40 WORLD’S BEST BOXERS PENALIZING BOXERS + + ® By David Greisman By Norm Frauenheim #3 #13 66 DAN GOOSSEN: 1949-2014 82 TRAGIC TURN THE LATE PROMOTER THE DEMISE OF HEAVYWEIGHT #12 #26 #11 #8 #29 SO LONG CANELO BEST I TO A GEM s HBO FACED DAN GOOSSEN WHAT ALVAREZ’S HALL OF FAMER MADE THE BUSINESS ROBERTO DURAN DREAMED BIG AND HAD FUN ALEJANDRO LAVORANTE 2015 JANUARY MOVE MEANS FOR MORE FUN P.66 THE FUTURE P.70 REVEALS HIS TOP $8.95 OPPONENTS P.20 By Steve Springer By Randy Roberts COVER PHOTOS: MAYWEATHER: ETHAN MILLER/ GETTY IMAGES; GOLOVKIN: ALEXIS CUAREZMA/GETTY 70 CANELO’S BIG MOVE IMAGES; KHAN/FROCH: SCOTT HEAVEY; ALVAREZ: CHRIS TROTMAN; PACQUIAO: JOHN GURZINSKI; HOW HIS JUMP TO HBO COTTO: RICK SCHULTZ: HOPKINS: ELSA/GOLDEN BOY; WILL IMPACT THE SPORT MAIDANA: RONALD MARTINEZ; DANNY GARCIA: AL BELLO; KLITSCHKO: DANIEL ROLAND/AFP/GETTY By Ron Borges IMAGES; BRONER: JEFF BOTTARI DENIS POROY/GETTY IMAGES DENIS POROY/GETTY 1.15 / RINGTV.COM 3 DEPARTMENTS 6 RINGSIDE 7 OPENING SHOTS 12 COME OUT WRITING 15 ROLL WITH THE PUNCHES Jabs and Straight Writes by Thomas Hauser 20 BEST I FACED: ROBERTO DURAN By Tom Gray 22 READY TO GRUMBLE By David Greisman 25 OUTSIDE THE ROPES By Brian Harty 27 PERFECT EXECUTION By Bernard Hopkins 32 RING RATINGS PACKAGE 86 LETTERS FROM EUROPE By Gareth A Davies 90 DOUGIEÕS MAILBAG By Doug Fischer 92 NEW FACES: JOSEPH DIAZ JR. -

Box'tag Information Guide

BBooxx’’TTaagg IInnffoorrmmaattiioonn GGuuiiddee IIddeeaass ffoorr CCooaacchheess aanndd AAtthhlleetteess Paul Perkins Box’Tag Information Guide – Ideas for coaches and athletes Table of contents 1. SUMMARY………………………………………………………………………………....5 1.1 Purpose…………………………………………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Aim...……………………………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Concept of Box’Tag……..………………………………………………………………………………….5 1.4 Values of Box’Tag...………………………………………………………………………………………...5 1.5 Mission of Box’Tag......……………………………………………………………………………….........5 1.6 Scope…………..……………………………………………………………………………………..................5 1.7 Methodology...………....…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.8 Terminology………………………………………………………………………………………….…........6 1.9 Intention………………………………………………………………………………………………….........6 1.10 Potential users…………...……………………………………………………………............................6 1.11 Maximise the use of this guide………………………………………………………………………7 2. INTRODUCTION..……………..……………………………………………………......9 3. COMPETITION………………....…………….….…………………………………....11 3.1 Concept….……………………………………………………………………………………………….…...11 3.2 Purpose………………………………………………………………………………………………….……11 3.3 Rules………...…………………………………………………………………………………………….......11 3.4 Conduct and behavior………………………………………………………………………….……….11 3.5 Prerequisites………….…...…………………………………………………………………………........11 3.6 Preferred distance……….…………………………………………………………………………........11 3.7 Preferred attacking actions………..……………………………………………………..................11 3.8 Preferred defensive action…...………………………………………………………………….…...12 3.9 Tactical appreciations……………………………………………………..........................................12 -

ORTHODOX STANCE TEACHER RESOURCE PACKAGE Prepared By: Susan Starkman, B.A., M.Ed

ORTHODOX STANCE TEACHER RESOURCE PACKAGE Prepared by: Susan Starkman, B.A., M.Ed Synopsis: Dimitriy Salita is a Russian immigrant, professional boxer and religious Jew. Orthodox Stance portrays his integration of these seemingly disparate and incompatible cultures, ultimately amalgamating both his pursuit of a professional boxing title with his devotion to Orthodox Judaism. In the end, the film is not just about boxing and religion, but about a young man’s search for meaningful expression. Significance of Title In boxing terms, an orthodox stance refers to the traditional right-handed boxing position (as opposed to a left-handed, or “southpaw” stance). In the context of the film, the title is a clever play on words that incorporates both the language of boxing and the strict branch of Orthodox Judaism that Dimitriy Salita practises. Context After reading an article in The Washington Post about Dimitriy Salita, director Jason Hutt contacted Salita’s rabbi and arranged to meet Dimitriy. According to Hutt, “after reading the article and meeting Dimitriy, it wasn’t the anomalous ‘religious Jewish boxer’ or the ‘will he become the next Jewish champ?’ angles that attracted me, but rather the diverse and wholly original characters that intersect at Dimitriy – an elderly African-American trainer, a Hasidic rabbi, a Las Vegas boxing promoter; as well as the diversity of Dimitriy’s experience – a Russian immigrant, a religious Jew, a top boxing prospect” (Orthodox Stance media kit). Indeed, what sets Orthodox Stance apart from other films in the boxing genre is its focus on how a sport like boxing can bridge racial, ethnic and religious divisions, uniting people from disparate backgrounds.