1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conditionality Impact and Prejudice in EU Turkey Relations

CONDITIONALITY, IMPACT AND PREJUDICE IN EU-TURKEY RELATIONS IAI-TEPAV REPORT edited by Nathalie Tocci Quaderni IAI ISTITUTO AFFARI INTERNAZIONALI This Quaderno has been made possible by the support of TEPAV and the Compagnia di San Paolo, IAI’s strategic partner. Quaderni IAI Direzione: Roberto Aliboni Redazione: Sandra Passariello Tipografia Città Nuova della P.A.M.O.M., Via S. Romano in Garfagnana, 23 - 00148 Roma - tel. 066530467 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface, Nathalie Tocci 5 Report Unpacking European Discourses: Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations, Nathalie Tocci 7 1. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Poland, Andrzej Ananicz 33 2. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Slovenia and ‘New Europe’, Borut Grgic 42 3. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Austria, Cengiz Günay 46 4. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Greece, Kostas Ifantis 58 5. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A ‘Northern’ View, Dietrich Jung 66 6. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from France, Anne-Marie Le Gloannec 75 7. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Brussels, Luigi Narbone 84 8. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice in EU-Turkey Relations: A View from Finland, Hanna Ojanen 93 9. Turkey’s EU Bid: A View from Germany, Constanze Stelzenmüller 105 10. The United Kingdom and Turkish Accession: The Enlargement Instinct Prevails, Richard G. Whitman 119 11. Conditionality, Impact and Prejudice: A Concluding View from Turkey, Mustafa Aydin and Asli Toksabay Esen 129 Chronology, by Marcello Vitale 141 Glossary, by Marcello Vitale 147 Note on Contributors 152 3 4 PREFACE Since 1999, EU-Turkey relations have become the focus of growing aca- demic and policy interest in Europe. -

Der Oberbergische Kreis Auf Einen Blick (Stand: Dezember 2008)

Der Oberbergische Kreis auf einen Blick Der dem nördlichen rechtsrheinischen Schiefergebirge zugehörige Oberbergi- sche Kreis ist ein Übergangsgebiet zwischen der Talebene des Rheins und dem sauerländischen Bergland. Das Gummersbacher Bergland in der Kreismit- te bildet den höchsten Teil des Bergischen Landes. Dort sind zugleich die Quellgebiete der Agger und der Wupper. Schwerpunkte verdichteter Siedlung liegen in den industriedurchsetzten Tälern. In seiner derzeitigen Form entstand der Oberbergische Kreis durch die kom- munale Neugliederung zum 1.1.1975. Er zeichnet sich in besonderer Weise durch landschaftlichen Zusammenhang, Einheitlichkeit der Siedlungsstruktur und gemeinsame historische Beziehungen aus. Die aktuellen Berufspendler- verflechtungen weisen den Kreis als eigenständigen Wirtschaftsraum aus. Oberberg ist zwar Teil des hochverdichteten Agglomerationsraumes an Rhein und Ruhr, ist jedoch deutlich anders strukturiert als die ballungskernnahen Kreise. Derzeit weist der Oberbergische Kreis bei einer Fläche von gut 918 Km² rund 286.000 Einwohner auf. Die Industrie ist mittelständisch. Maschinen- und Fahrzeugbau, Edelstahlerzeugung, Stahl- und Leichtmetallbau, Eisen-, Blech- und Metallverarbeitung, Elektrotechnische Industrie und Kunststoffverarbei- tung sind die wichtigsten Branchen. Oberberg ist Bestandteil des Agglomera- tionsraumes Köln. Solche hochverdichteten Wirtschaftsräume sind Kristallisa- tionspunkte für Innovationen. Letzteres kommt u. a. in der Patentdichte (Pa- tentanmeldungen je 100.000 Einwohner) zum Ausdruck. -

LASER CUTTING. Individual

ALLES. GUT. LASER CUTTING. Individual. Precise. This long-established accurate technology makes possibly required rework due to thermal distortion unnecessary and offers § Low thermal distortion and small heat-affected zone despite thermal cutting § Free selection and changeable part geometry, absolutely no arising tool costs § True to gauge, ready-to-fit parts, nearly square cut edges, free of oxide in stainless steel § Simplified subsequent processing in your company by marking the parts or attaching subsidiary lines / points with a laser engraver Technical details. Format: up to 2,000 x 4,000 mm Sheet gauge: Stainless steel: up to 30 mm Steel: up to 25 mm Aluminium: up to 15 mm Subsequent processing: Drilling, thread cutting, edging, rolling, chamfering, welding work in company possible Do you have any questions regarding our laser cutting services? Please contact Alexander Caspari: [email protected] W. Albrecht GmbH & Co. KG | Schlosserstr. 9–11 | 51789 Lindlar, Germany | Tel.: +49 2266 9006-0 ALBRECHT-DBB.DE ALLES. GUT. PLASMA CUTTING. Perfectly. Separated. This clean and highly flexible separation process offers § Cost-efficient thermal cutting § Unproblematic cuts on large sheet gauges § Low wastage – especially when compared to bar stock § Reduced use of material by using intermediate gauges We also offer a 24 h service. Technical details. Format: up to 2,500 x 6,000 mm Sheet gauge: Stainless steel: up to 100 mm Steel: up to 40 mm (plasma-burning) up to 100 mm (autogenous burning) Intermediate gauges: of 16/18/22/26/28/32 mm in stock Dry cutting: from 3 to 120 mm Underwater plasma: up to 50 mm Authorised to reissue 3.1 and 3.2 according to DIN EN 10204 stamps by TÜV: along with in-company US test Do you have any questions regarding our plasma cutting services? Please contact Alexander Caspari: [email protected] W. -

Gemeinde Lindlar Der Bürgermeister

Gemeinde Lindlar Der Bürgermeister Beteiligungsbericht zum 31. Dezember 2016 gemäß § 117 GO NRW Lindlar, den 17. Oktober 2016 Gemeinde Lindlar Beteiligungsbericht Der Bürgermeister 31.12.2016 Inhaltsverzeichnis A. ALLGEMEINER TEIL 3 I Grundlagen 3 II Überblick über die Beteiligungen der Gemeinde Lindlar 6 III Wesentliche Finanz- und Leistungsbeziehungen 7 IV Bericht über die wirtschaftliche Tätigkeit 8 B. WIRTSCHAFTLICHE BETEILIGUNGEN DER GEMEINDE LINDLAR 9 BGW Bau-, Grundstücks- und Wirtschaftsförderungsgesellschaft mbH 9 SFL Sport- und Freizeitbad Lindlar GmbH 19 OAG Oberbergische Aufbau GmbH 26 GTC Gründer- und TechnologieCentrum Gummersbach GmbH 32 Volksbank Wipperfürth-Lindlar eG 37 Wasserversorgungsgenossenschaft Schmitzhöhe eG 41 EGBL Energiegenossenschaft Bergisches Land eG 45 KoPart eG 48 C. NICHTWIRTSCHAFTLICHE BETEILIGUNGEN DER GEMEINDE LINDLAR 53 Gemeindewerk Wasser und Abwasser 52 TeBEL Technischer Betrieb Engelskirchen-Lindlar 56 Civitec 60 Seite 2 Gemeinde Lindlar Beteiligungsbericht Der Bürgermeister 31.12.2016 A. Allgemeiner Teil I Grundlagen Als Gebietskörperschaften haben die Gemeinden eine Vielzahl von Aufgaben zu erfüllen. Neben dem verfassungsrechtlich garantierten Recht, alle Angelegenheiten der örtlichen Gemeinschaft in eigener Verantwortung zu regeln, wodurch den Gemeinden ein Aufgabenbestand zugesichert ist, beinhaltet das Recht der kommunalen Selbstverwaltung auch die Befugnis, diese Angelegenheiten nach eigener Entscheidung und in eigener Verwaltung zu führen. Die Gemeinden können deshalb nicht nur darüber entscheiden, -

Bestens Informiert Sein Regional Investor

... BESTENS INFORMIERT SEIN REGIONAL INVESTOR Jennifer surft hier scheinbar ganz gemütlich durch die Weltgeschichte. Aber in Wirklichkeit unterstützt sie die Region. Denn die Energie, die sie benötigt, kommt von AggerEnergie – dem einzigen Energieversorger, bei dem von jedem Euro Gemeinsam für unsere Region Umsatz immer 37 Cent in unsere Region zurückfließen. Mehr auf aggerenergie.de 1505541_Anzeigen_Shooting_A5_quer_V2.indd 1 22.06.15 17:27 Inhaltsverzeichnis WILLKOMMEN BÜRGER-SERVICE Bergneustadt – Informativ . 5 Das Rathaus . 28 Heiraten in Bergneustadt . 29 WISSENSWERTES IN ALLER KÜRZE BERGNEUSTADT IM BLICK Zahlen, Daten, Fakten . 6 Bevölkerungsentwicklung / Flächennutzung . 7 Das Amtsblatt von Bergneustadt . 30 Ortsteile . 8 Personennahverkehr/ Taxi /Parken . 10 Bergneustadts Innenstadt . 11 Anzeigen . 32 Der Stadtrat und seine Mitglieder . 12 Impressum . 42 KONTAKTE UND ADRESSEN Öffentliche Einrichtungen / Notrufe . 15 Kinderbetreuung . 16 Bildungseinrichtungen . 17 Soziale Einrichtungen . 18 Ehrenamt . 19 Kulturelle Einrichtungen . 19 Einrichtungen für Senioren . 20 Einrichtungen für Jugendliche . 20 Kirchen und religiöse Gemeinschaften . 21 Apotheken / Krankenhaus / Notfallnummern . 22 Ärzte . 23 Sonstige Gesundheitsangebote . 24 Naherholung & Tourismus . 25 Vereine . 26 INHALT 3 Bergneustadt Unser Motto „Informativ, servicefreundlich und hilfreich.“ Ein Service für alle, die mehr über Bergneustadt wissen wollen, ist unsere Informationsbroschüre. Die erste Ausgabe der Informationsbroschüre der Stadt zialen Einrichtungen und der ärztlichen Versorgung in Bergneustadt . Bergneustadt ist erschienen . Sie ist ein umfassendes und Beachtenswert ist auch die lange Liste der Vereine im Stadtgebiet . Ist informatives Nachschlagewerk für Gäste, Neubürger, Bür- da vielleicht was für Sie dabei? gerschaft und Unternehmen unserer Stadt . Sie wird regelmäßig aktua- Besser informiert: lisiert und liegt in der Stadtverwaltung sowie in der Tourist-Information Das Heft dient aber nicht allein der Orientierung, es soll Sie auch an- im Heimatmuseum aus . -

How to Find Us

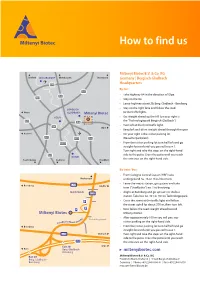

How to find us Miltenyi Biotec B.V. & Co. KG Krefeld DÜSSELDORF Oberhausen Dortmund Germany | Bergisch Gladbach A 46 Headquarters By car: A 1 • Take highway A4 in the direction of Olpe. A 3 A 57 • Stay on the A4. • Leave highway at exit 20, Berg. Gladbach - Bensberg. • Stay on the right lane and follow the road BERGISCH Venlo GLADBACH Miltenyi Biotec to the traffic lights. KÖLN • Go straight ahead up the hill (on your right is A 61 the “Technologiepark Bergisch Gladbach”). A 4 • Turn left at the third traffic light. A 4 Olpe • Keep left and drive straight ahead through the gate. Aachen • On your right is the visitor parking lot A 1 A 59 A 3 (Besucherparkplatz). A 555 • From the visitor parking lot turn half left and go straight forward until you passed house 1. Turn right and take the steps on the right-hand A 61 side to the patio. Cross the patio until you reach BONN Saarbrücken Koblenz Frankfurt the entrance on the right-hand side. By train / bus: • From Cologne Central Station (HBF) take Herkenrath underground no. 16 or 18 to Neumarkt. • Leave the metro station, go upstairs and take Bensberg L 298 Lindlar tram (“Stadtbahn“) no. 1 to Bensberg. MOITZFELD L 195 • Alight at Bensberg and go upstairs to the bus station. Take bus no. 421 or 454 to Technologiepark. P • Cross the street at the traffic light and follow the street uphill for about 200 m, then turn left. P P • Now follow the road straight ahead toward Miltenyi Biotec Miltenyi Biotec. -

Der Oberbergische Kreis Auf Einen Blick

Der Oberbergische Kreis auf einen Blick Der dem nördlichen rechtsrheinischen Schiefergebirge zugehörige Oberbergische Kreis ist ein Übergangsgebiet zwischen der Talebene des Rheins und dem sauerländischen Bergland. Das Gummersbacher Bergland in der Kreismitte bildet den höchsten Teil des Bergischen Landes. Dort sind zugleich die Quellgebiete der Agger und der Wupper. Schwerpunkte verdichteter Siedlung liegen in den industriedurchsetzten Tälern. In seiner derzeitigen Form entstand der Oberbergische Kreis durch die kommunale Neugliederung zum 1.1.1975. Er zeichnet sich in besonde- rer Weise durch landschaftlichen Zusammenhang, Einheitlichkeit der Siedlungsstruktur und gemeinsame historische Beziehungen aus. Die aktuellen Berufspendlerverflechtungen weisen den Kreis als eigenstän- digen Wirtschaftsraum aus. Oberberg ist zwar Teil des hochverdichte- ten Agglomerationsraumes an Rhein und Ruhr, weist jedoch deutlich andere Strukturen auf als die ballungskernnahen Kreise. Derzeit hat der Oberbergische Kreis bei einer Fläche von gut 918 km² rund 290.000 Einwohner. Die Industrie ist mittelständisch. Maschinen- bau, Fahrzeugbau, Edelstahlerzeugung, Stahl- und Leichtmetallbau, Eisen-, Blech- und Metallverarbeitung, Elektrotechnische Industrie und Kunststoffverarbeitung sind die wichtigsten Branchen. Prognosen las- sen bis 2010 weiteres Wachstum an Einwohnern und Arbeitsplätzen erwarten. Als zentraler Bestandteil des Naturparks Bergisches Land ist der Kreis Ziel von zahlreichen Erholungssuchenden. Wichtiger Standortfaktor ist die Abteilung Gummersbach der Fachhoch- schule Köln. Sie hat ein für die Wirtschaft in Oberberg sehr leistungsfä- higes Fächerspektrum. In den Standort eingebunden ist ein Studien- zentrum der Fernuniversität Hagen. Die Verkehrsverbindungen nach Köln (RB 25 'Oberbergische Bahn' und BAB A 4) und in Nord-Süd-Richtung (BAB A 45) sind gut. Die für 2005 vorgesehene Weiterführung der RB 25 bis Lüdenscheid stellt eine we- sentliche Verbesserung der Anbindung an den nord- und mitteldeut- schen Raum dar. -

Zu- Und Fortzüge Reichshof; Zahlen, Daten, Fakten; 11/2013

Zahlen, Daten, Zu- und Fortzüge Fakten Reichshof 11 | 2013 Daten 2011 OBERBERGISCHER KREIS DER LANDRAT Zahlen, Daten, Fakten 11 | 2013 Zum Download Zu- und Fortzüge Reichshof Mit dieser Ausgabe der Zahlen, Daten, Fakten liegt Ihnen eine von insgesamt 13 Ausgaben über die Zu- und Fortzüge in die kreisangehörigen Städte und Gemeinden vor. Diese ergänzen den als Ausgabe 01/2012 der Reihe Zahlen, Daten, Fakten erschienenen Demograiebericht Oberbergischer Kreis. Alle Ausgaben inden Sie auf der Internetseite des Demograieforums Ober- berg unter www. demograie-oberberg.de >> Demograiebericht >> Zu- und Fortzüge in den Städte und Gemeinden im Oberbergischen Kreis. Wie auch dem Demograiebericht liegen den Zu- und Fortzügen die amtlichen Daten von IT.NRW zum 31.12.2011 zugrunde. Im Einzelfall kann es Abweichungen von den gemeindlichen Meldedaten ge- ben. Zahlen, Daten, Fakten Fragen zu den Zu- und Fortzügen? Ausgabe 1/2012 Demograiebericht Auskunft erteilt beim Oberbergischer Kreis Amt für Immobilienwirtschaft und Infrastruktur: Daten zum 31.12.2011 Kerstin Gipperich, Telefon: 02261 88 - 2318 www.demograie-oberberg.de E-Mail: [email protected] Ergänzungen zum Demograiebericht Die folgenden Veröffentlichungen ergänzen den Demograiebericht. Besonders möchten wir auf die für alle Kommunen erstellten, Präsentationen „Demogra- iebericht Oberbergischer Kreis“ hinweisen. Diese Präsentationen können Sie verwenden, um in Ihrem Verein oder Ihrer Organisation über die demograische Entwicklung Ihres Ortes zu informieren. Impressum Herausgeber: Oberbergischer -

Oberbergischer Kreis Der Landrat

Oberbergischer Kreis Der Landrat Allgemeinverfügung zur Bestimmung des Fahrweges für die Beförderung von gefährlichen Gütern nach § 7 Abs. 3 GGVSE im Bereich des Oberbergischen Kreises Anlage 1: Positivnetz Erklärung der Abkürzungen: B= Bundesstraße L= Landstraße K= Kreisstraße 1. B 55 zwischen der Abzweigung der L 173 in Bergneustadt - Pernze und der Abzweigung der L 302 in Engelskirchen - Hardt, tangierend die Gemeinden Bergneustadt, Gummersbach und Engelskir- chen, 2. B 55 zwischen der Abzweigung der Straße Haus Alsbach in Engelskirchen und der Kreisgrenze zum Rheinisch-Bergischen Kreis, tangierend die Gemeinde Engelskirchen, 3. B 56 zwischen der BAB A 4 AS Wiehl/Bielstein und der Kreisgrenze zum Rhein-Sieg-Kreis, tangierend die Gemeinden Engelskirchen und Wiehl, 4. B 56 zwischen der BAB A 4 AS Gummersbach und der B 256 in Höhe der Abfahrt Rospetalstraße (B 256), tangierend die Stadtgemeinde Gummersbach, 5. B 229 zwischen der Kreisgrenze zum Märkischen Kreis und der Kreisgrenze zur kreisfreien Stadt Rem- scheid, tangierend die Stadtgemeinde Radevormwald, 6. B 237 zwischen der Kreisgrenze zum Märkischen Kreis und der Kreisgrenze zur kreisfreien Stadt Rem- scheid, tangierend die Stadtgemeinden Wipperfürth und Hückeswagen, 7. B 256 zwischen der B 237 in Wipperfürth - Ohl und der B 56/Rospetalstraße in Gummersbach, tangie- rend die Gemeinden Wipperfürth, Marienheide und Gummersbach, Seite 2 8. B 256 zwischen der B 55 in Gummersbach - Derschlag und der L336 in Reichshof - Sengelbusch sowie bis zur L 344, tangierend die Gemeinden Gummersbach und Reichshof, 9. B 256 zwischen der B 478 in Waldbröl und der Abzweigung der Friedrich-Engels-Straße in Waldbröl - Hermesdorf, tangierend die Stadtgemeinde Waldbröl, 10. -

Kreisverwaltung Obk

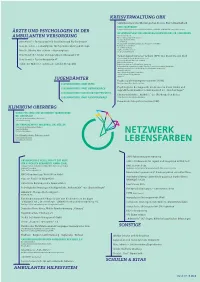

KREISVERWALTUNG OBK Sozialdezernent des Oberbergischen Kreises, Herr Schmallenbach KREISJUGENDAMT ÄRZTE UND PSYCHOLOGEN IN DER Bergneustadt/Engelskirchen/Lindlar/Marienheid/Morsbach/Nümbrecht/Waldbröl/Reichshof/Hückeswagen GESUNDHEITSAMT DES OBERBERGISCHEN KREISES, FR. ELVERMANN Amtsärztlicher Dienst AMBULANTEN VERSORGUNG Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitsdienst Sozialpsychiatrischer Dienst Herr Althoff > Facharztpraxis für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie Soziale Dienste Beratungsstelle für Familienplanung und Schwangerschaftskonflikte Frau Dr. Frohne > Facharztpraxis für Psychiatrie und Psychotherapie Kommunaler sozialer Dienst Gesundheitsförderung Projekt „Verrückt? Na und?“ Herr Dr. Olbeter, Herr Stüttem > Hausarztpraxis Pilotprojekt Familienpaten Frau Wendrich > Kinder und Jugendpsychotherapeutin VT Gemeindepsychiatrischen Verbund (GPV) Süd, Kreismitte und Nord Caritasverband für den Oberbergischen Kreis e.V. Frau Korneli > Psychotherapeutin VT Curt-von-Knobelsdorff-Haus Radevormwald Diakonie Michaelshoven Sabine zur Mühlen > systemische Familientherapeutin Diakonisches Werk des Ev. Kirchenkreises Lennep e.V. Kreiskrankenhaus Gummersbach GmbH / Zentrum für Seelische Gesundheit Marienheide Oberbergische Gesellschaft zur Hilfe für psychisch Behinderte GmbH (OGB) Oberbergischer Kreis RAPS Gemeinnützige Werkstätten GmbH Theodor Fliedner Stiftung, Waldruhe JUGENDÄMTER Alpha e.V. Psychosoziale Arbeitsgemeinschaften (PSAG) JUGENDAMT DER STADT WIEHL Kinder und Jugendliche/Erwachsene/Sucht Psychologische Beraungsstelle des Kreises für Eltern, Kinder -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 109 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 151 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, APRIL 18, 2005 No. 46 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE Accordingly (at 2 o’clock and 4 min- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The utes p.m.), under its previous order, the pore (Mr. RADANOVICH). Chair will lead the House in the Pledge House adjourned until tomorrow, Tues- day, April 19, 2005, at 12:30 p.m., for f of Allegiance. The SPEAKER pro tempore led the morning hour debates. DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Pledge of Allegiance as follows: PRO TEMPORE I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the f The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- United States of America, and to the Repub- lic for which it stands, one nation under God, EXECUTIVE COMMUNICATIONS, fore the House the following commu- indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. ETC. nication from the Speaker: f WASHINGTON, DC, Under clause 8 of rule XII, executive April 18, 2005. COMMUNICATION FROM THE communications were taken from the I hereby appoint the Honorable GEORGE CLERK OF THE HOUSE Speaker’s table and referred as follows: RADANOVICH to act as Speaker pro tempore The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- 1664. A letter from the Director, Regu- on this day. fore the House the following commu- latory Review Group, Farm Service Agency, J. DENNIS HASTERT, nication from the Clerk of the House of Department of Agriculture, transmitting the Speaker of the House of Representatives. -

Wohnungsmarktanalyse Für Den Oberbergischen Kreis - Endbericht

empirica Qualitative Marktforschung, Stadt- und Strukturforschung GmbH Kaiserstr. 29 • D- 53113 Bonn Tel.: 0228 / 914 89-0 Fax: 0228 / 217 410 [email protected] www.empirica-institut.de Wohnungsmarktanalyse für den Oberbergischen Kreis - Endbericht - Auftraggeber: Die Oberbergischen Sparkassen: Kreissparkasse Köln Sparkasse Gummersbach-Bergneustadt Sparkasse der Homburgischen Gemeinden in Wiehl Sparkasse Radevormwald-Hückeswagen Ansprechpartner: Petra Heising, Iris Fryczewski, Katrin Wilbert Projektnummer: 2007113 Bonn: August 2008 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 1. Einleitung 1 1.1 Zukunft des Wohnungsmarkts in unsicheren Zeiten 1 1.2 Ausgangssituation: Ländliche Lage am Rande einer Wachstumsregion 2 2. Wirtschaft und Demografie der letzten zehn Jahre 4 2.1 Wirtschaft und Pendlerströme 4 2.1.1 Wirtschaftsentwicklung mit eigener Dynamik 4 2.1.2 Wirtschaftswachstum vor allem im Norden und Süden des Kreises 7 2.2 Bevölkerung und Wanderungen 12 2.2.1 Einwohnerentwicklung im Abwärtsrutsch: Zuzug von Familien bleibt aus 12 2.2.2 Gemeinden im Süden profitieren: Verjüngung durch Zuwanderung 18 2.3 Fazit: Abwanderung trotz Wirtschaftswachstum 28 3. Wohnungsmarkt und Baulandpolitik 29 3.1 Wohnungsbestand nach Baualter 29 3.2 Baufertigstellungen 32 3.2.1 Sinkende Tendenz in der Bautätigkeit des Oberbergischen Kreises 32 3.2.2 Unterschiedliche Tendenzen der Bautätigkeit in den Teilräumen des Oberbergischen Kreises 34 3.3 Bodenpreisgefälle und Leerstand 35 3.4 Derzeitige Baulandpolitik und demnach zukünftig zu erwartende Qualitäten 39 3.4.1 Unterschiedliche