British Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Nestling Diet on Growth and Adult Size of Zebra Finches (Poephila Guttata )

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VOL. 104 APRIL 1987 NO. 2 EFFECTS OF NESTLING DIET ON GROWTH AND ADULT SIZE OF ZEBRA FINCHES (POEPHILA GUTTATA ) PETER T. BOAG Departmentof Biology,Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario K7L 3N6, Canada Al•STRACT.--Manipulationof the diet of Zebra Finch (Poephilaguttata) nestlings in the laboratoryshowed that a low-quality diet reducedgrowth ratesof nine externalmorpholog- ical characters,while a high-quality diet increasedgrowth rates.The growth of plumage characterswas least affectedby diet, while growth ratesof tarsusand masswere most af- fected. The treatments also produced differencesin the adult size of experimental birds, differencesnot evident in either their parentsor their own offspring.Diet quality had the strongestimpact on adult massand tarsuslength, while plumage and beak measurements were less affected. Analysis using principal componentsand characterratios showed that the shapeof experimentalbirds was affectedby the experimentaldiets, but to a minor extent comparedwith changesin overall size. Significantshape changes involved ratiosbetween fast- and slow-growingcharacters. The ratios of charactersthat grow at similar, slow rates (e.g. beak shape) were not affected by the diets. Environmental sourcesof morphological variation should not be neglectedin studiesof phenotypicvariation in birds. Received5 June 1986, accepted30 October1986. MORPHOLOGICAL differences between indi- fitness, and weather was seen in the nonran- vidual birds are often assignedfunctional sig- dom survival of House Sparrows collected by nificance, whether those individuals are of dif- Hiram Bumpus following a winter storm ferent species,different sexes,or different-size (O'Donald 1973, Fleischer and Johnston 1982). members of the same sex (Hamilton 1961, Se- Recently, investigators have tried to dem- lander 1966,Clark 1979,James 1982). -

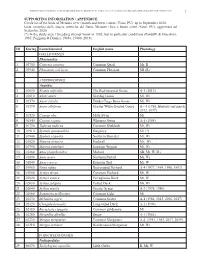

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Birds Checklist STEPPE BIRDS of CALATRAVA

www.naturaindomita.com BIRDS CHECKLIST C = Common R = Resident. All year round. Steppe Birds of Calatrava LC = Less Common S = Spring & Summer. Usually breeding. Calatrava Steppes and Guadiana Steppes R = Rare or Scarce W = Autumn & Winter M = Only on migration Familia Nombre Científico Inglés Español Frequency Season 1 Podicipedidae Podiceps nigricollis Black-Necked Grebe Zampullín Cuellinegro 2 Podicipedidae Tachybaptus ruficollis Little Grebe Zampullín Común 3 Podicipedidae Podiceps cristatus Great Crested Grebe Somormujo Lavanco 4 Phalacrocoracidae Phalacrocorax carbo Great Cormorant Cormorán Grande 5 Ardeidae Botaurus stellaris Great Bittern Avetoro 6 Ardeidae Ixobrychus minutus Little Bittern Avetorillo Común R S 7 Ardeidae Nycticorax nycticorax Black-Crowned Night Heron Martinete Común LC S 8 Ardeidae Bubulcus ibis Cattle Egret Garcilla Bueyera CR 9 Ardeidae Ardeola ralloides Squacco Heron Garcilla Cangrejera RS 10 Ardeidae Egretta garzetta Little Egret Garceta Común CR 11 Ardeidae Egretta alba Great Egret Garceta Grande LC R 12 Ardeidae Ardea cinerea Grey Heron Garza Real LC R 13 Ardeidae Ardea purpurea Purple Heron Garza Imperial RS 14 Ciconiidae Ciconia ciconia White Stork Cigüeña Blanca CR 15 Ciconiidae Ciconia nigra Black Stork Cigüeña Negra 16 Threskiornithidae Plegadis falcinellus Glossy Ibis Morito Común LC S 17 Threskiornithidae Platalea leucorodia Eurasian Spoonbill Espátula Común LC S 18 Phoenicopteridae Phoenicopterus ruber Greater Flamingo Flamenco Común 19 Anatidae Anser albifrons Greater White-Fronted Goose Ánsar -

Urbanisation and Nest Building in Birds Reynolds, Silas; Ibáñezálamo, Juan Diego; Sumasgutner, Petra; Mainwaring, Mark

University of Birmingham Urbanisation and nest building in birds Reynolds, Silas; IbáñezÁlamo, Juan Diego; Sumasgutner, Petra; Mainwaring, Mark DOI: 10.1007/s10336-019-01657-8 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Reynolds, S, IbáñezÁlamo, JD, Sumasgutner, P & Mainwaring, M 2019, 'Urbanisation and nest building in birds: a review of threats and opportunities', Journal of Ornithology, vol. 160, pp. 841-860. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10336-019-01657-8 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

Weed Management Increases the Detrimental Effect of an Invasive

Biological Conservation 233 (2019) 93–101 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Weed management increases the detrimental effect of an invasive parasite on arboreal Darwin's finches T Arno Cimadoma, Heinke Jägerb, Christian H. Schulzec, Rebecca Hood-Nowotnyd, ⁎ Christian Wappla, Sabine Tebbicha, a Department of Behavioural Biology, University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria b Charles Darwin Research Station, Charles Darwin Foundation, Santa Cruz Island, Galápagos, Ecuador c Department of Botany and Biodiversity Research, University of Vienna, 1030 Vienna, Austria d Institute of Soil Research, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, 1180 Vienna, Austria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The detrimental effects of invasive parasites on hosts often increase under poor environmental conditions. Both Philornis downsi natural fluctuations in environmental conditions and habitat management measures can temporarily cause Darwin's finches adverse environmental effects. In this study, we investigated the interaction between the invasive parasitic fly Invasive species Philornis downsi, control of invasive plants and precipitation on the breeding success of Darwin's finches. Parasitism Introduced plant species have invaded a unique forest on the Galapagos island of Santa Cruz, which is a key Arthropod biomass habitat for Darwin's finches. The Galapagos National Park Directorate applies manual control and herbicides to Weed management combat this invasion. We hypothesized that these measures led to a reduction in the arthropod food supply during chick rearing, which in turn caused mortality in chicks that were already weakened by parasitism. We compared food availability in three study sites of varying degrees of weed management. To assess the interaction of parasitism and weed management, we experimentally reduced P. -

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material Aleksi Lehikoinen*, Alison Johnston & Dario Massimino 2021: Climate and land use changes: similarity in range and abundance changes of birds in Finland and Great Britain and structure of a breeding. — Ornis Fennica 98: 1–15. A. Lehikoinen, The Helsinki Lab of Ornithology, Finnish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 17, Helsinki, Finland * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] A. Johnston, The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA. Department of Zoology, Conservation Science Group, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. The British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU, UK D. Massimino, The British Trust for Ornithology, The Nunnery, Thetford, Norfolk IP24 2PU, UK Supplementary Table 1. Annual rate of range size change and shift in mean weighted latitude of 56 species in Britain and Finland, that were used in distribution analyses. The main habitat type (Hab; F = forest, W = wetland, O = open), mean northerness in terms of latitude of distribution (Lat) as well as taxonomy (Genus, Family and Order) of species are given. Range change Distribution shift Species Hab Lat Genus Family Order Britain Finland Britain Finland Mute Swan Cygnus olor 1.002 1.038 0.828 2.536 W 0.271 Cygnus Anatidae Anseriformes Canada Goose Branta canadensis 1.024 1.155 2.482 3.781 W 0.244 Branta Anatidae Anseriformes Gadwall Anas strepera 1.039 1.105 –1.095 2.453 W 0.309 Mareca Anatidae Anseriformes Garganey Anas querquedula 1.01 0.997 2.91 -

Checklist of Alaska Birds

CHECKLIST OF ALASKA BIRDS 22nd edition—2016 As of 1 January 2016 the list of avian taxa known in Alaska included 510 naturally-occurring species in 65 families and 20 orders. Phylogenetic sequence, limits of orders and families, and English and scientific names of species follow The A.O.U. Check-list of North American Birds (7th ed., American Ornithologists’ Union 1998) and supplements (through 2015). Founded on archived specimens, this checklist increasingly includes new species known in Alaska only from (archived) photos, videotapes, and/or audio recordings. An appended “unsubstantiated” list comprises an additional 24 species –including two species pairs—attributed to Alaska without specimen or photo substantiation. -

Type Specimens of Birds in the Collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 174 Type Specimens of Birds in the Collections of the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology Robert W. Storer Museum of Zoology and Department of Biology The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48 109-1079 Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN July 6, 1988 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 174 The publications of the Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, initiated in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, the Museum will supply a title page, table of contents, and an index to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of Occasional Papers, were established in 1916 and are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1079. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. -

Cultural Responses to the Migration of the Barn Swallow in Europe Ashleigh Green University of Melbourne

Cultural responses to the migration of the barn swallow in Europe Ashleigh Green University of Melbourne Abstract: This paper investigates the place of barn swallows in European folklore and science from the Bronze Age to the nineteenth century. It takes the swallow’s natural migratory patterns as a starting point, and investigates how different cultural groups across this period have responded to the bird’s departure in autumn and its subsequent return every spring. While my analysis is focused on classical European texts, including scientific and theological writings, I have also considered the swallow’s representation in art. The aim of this article is to build alongue durée account of how beliefs about the swallow have evolved over time, even as the bird’s migratory patterns have remained the same. As I argue, the influence of classical texts on medieval and Renaissance thought in Europe allows us to consider a temporal progression (and sometimes regression) in the way barn swallow migration was explained and understood. The barn swallow The barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) has two defining characteristics that have shaped how people living in Europe have responded to its presence over the centuries. The first relates to its movement across continents. The swallow migrates to Africa every autumn and returns to Asia in spring for breeding. Second, it is a bird that is often found in urban environments, typically nesting in or on buildings to rear its young.1 These two characteristics have meant that the barn swallow has been a feature of European life for centuries and has prompted a myriad of responses in science and folklore—particularly in Greek mythology. -

The First Record of Common House-Martin (Delichon Urbicum) for British Columbia. by Rick Toochin, Peter Hamel, Margo Hearne and Martin Williams

The First Record of Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) for British Columbia. By Rick Toochin, Peter Hamel, Margo Hearne and Martin Williams. Introduction and Distribution The Common House-Martin (Delichon urbicum) is a small passerine found in the Old World from Europe and Asia. There are 2 subspecies and most size differences between north and southern populations are clinal (Turner and Rose 1989). In Europe, the nominate subspecies (D. u. urbicum) is found breeding from Great Britain, to Russia, also in North Africa and across the Mediterranean Sea to Turkey and Israel and further east to central Asia (Mullarney and Zetterstrom 2009). This subspecies of the Common House-Martin winters throughout west and southeast Africa (Mullarney and Zetterstrom 2009). In Far East Asia, the subspecies (D. u. lagopodum) of Common-House Martin is a widespread breeding species from the Yenisei to North-east China, North-east Russia, Yakutia, Chukotka, north Koryakia coast and possibly in Kamchatka (Brazil 2009). The Common House-Martin is a rare migrant in Japan and Korea (Brazil 2009). This subspecies does winter in small numbers in South Eastern China, but the bulk of the population winters in Southeast Asia (Brazil 2009). In North America, the Common House-Martin is an accidental to casual vagrant (Dunn and Alderfer 2011). In Alaska, there is one specimen record of the Common House-Martin which belongs to the Asian subspecies (D. u. lagopodum), which is assumed to be the rest of the observations in Alaska, and this species is classified as casual with scattered records from Nome, St. Paul Island, Gambell, Buldir Island, St. -

Avibase Page 1Of 15

Avibase Page 1of 15 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Skåne 2 Number of species: 445 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 22 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2012-01-20 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2019. Checklist of the birds of Skåne. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc- eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=sesn&list=clements&format=1 [19/03/2019]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Ecography ECOG-00540 Thornton, D

Ecography ECOG-00540 Thornton, D. H. and Fletcher, Jr R. J. 2014. Body size and spatial scales in avian response to landscapes: a meta-analysis. – Ecography 37: xxx–xxx. Supplementary material Appendix 1: List of species and number of times each species appeared in the various studies of this meta‐analysis. Number of Species Family Order occurrences across studies Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, and Anas discors Waterfowl) Anseriformes 1 Anatidae (Ducks, Geese, and Anas platyrhynchos Waterfowl) Anseriformes 1 Archilochus colubris Trochilidae (Hummingbirds) Apodiformes 2 Selasphorus rufus Trochilidae (Hummingbirds) Apodiformes 1 Charadrius vociferus Charadriidae (Plovers and Lapwings) Charadriiformes 1 Vanellus vanellus Charadriidae (Plovers and Lapwings) Charadriiformes 1 Bartramia longicauda Scolopacidae (Sandpipers and Allies) Charadriiformes 1 Gallinago delicata Scolopacidae (Sandpipers and Allies) Charadriiformes 1 Limosa fedoa Scolopacidae (Sandpipers and Allies) Charadriiformes 1 Phalaropus tricolor Scolopacidae (Sandpipers and Allies) Charadriiformes 1 Columba oenas Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Columba palumbus Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Hemiphaga novaeseelandiae Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Patagioenas fasciata Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Patagioenas nigrirostris Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Phaps elegans Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Streptopelia turtur Columbidae (Pigeons and Doves) Columbiformes 1 Zenaida macroura Columbidae