Deterring Player Holdouts: Who Should Do It, How to Do It, and Why It Has to Be Done Basil M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Will Be Golden in Sochi?

February 2014 Volume 18 No. 1 Published by International Ice Hockey Federation Editor-in-Chief Horst Lichtner Editor Szymon Szemberg Design Adam Steiss Who will be golden in Sochi? Photos: Matthew Manor, Jukka Rautio / HHOF-IIHF Images, RIA Novosti Jukka Rautio / HHOF-IIHF Images, Matthew Manor, Photos: For two weeks in February, the Bolshoy Ice Dome will be the center of the hockey universe as the game's elite descend on Sochi, Russia for the 2014 Olympic Winter Games. nn The 2014 season is finally capped it off with a shocking 7-2 win over a previously n 2014 has already seen some exciting hockey as the here, and with it the XXII Olympic dominant Canadian team. Flash forward to 2014, where World Junior Championship concluded in Sweden. I would Winter Games. the Russians will host a Winter Olympics for the first time like to extend a sincere congratulations to the winners ever. While the hosts will undoubtedly ice a very strong Finland, and also to the city of Malmö for putting on an team that will be in the hunt to claim Olympic exceptional tournament. While the hosts were not able to RENÉ fasEL EDITORIAL gold, the outcome is far from certain. see their team take the gold, everyone who attended the games or who watched them on TV were treated to some This is a time that everyone around That is what makes this Winter Olympic tournament so fantastic hockey. the hockey world has looked forward intriguing. On the women’s side, the rivalry between Can- to ever since Sidney Crosby’s over- ada and the United States has never been hotter, but that There will be a few more things to look forward to once time goal capped off a memorable hockey tournament in doesn’t mean either team can look ahead to meeting each the Olympics wrap up. -

Hockey Pools for Profit: a Simulation Based Player Selection Strategy

HOCKEY POOLS FOR PROFIT: A SIMULATION BASED PLAYER SELECTION STRATEGY Amy E. Summers B.Sc., University of Northern British Columbia, 2003 A PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTEROF SCIENCE in the Department of Statistics and Actuarial Science @ Amy E. Summers 2005 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Fall 2005 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author APPROVAL Name: Amy E. Summers Degree: Master of Science Title of project: Hockey Pools for Profit: A Simulation Based Player Selection Strategy Examining Committee: Dr. Richard Lockhart Chair Dr. Tim Swartz Senior Supervisor Simon Fraser University Dr. Derek Bingham Supervisor Simon F'raser University Dr. Gary Parker External Examiner Simon Fraser University Date Approved: SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. -

ˉs All of Them Are in This Post Or If You Find That That Be What the Hail?

Hail, hail,soccer jersey,going to be the gang?¡¥s all of them are in this post Or if you find that that be what the hail? For the first a period of time seeing that if that's so,a person can be aware that,all of them are going to be the players have already been here and now Saturday as well as for going to be the four de.ent elem team meeting that marked the official start of Seahawks training camp. The club set made some all of them are the draft good debt consolidation moves might report everywhere in the a period of time on the basis of signing top are you aware Josh Wilson for more information on an all in one four-year,2011 nfl jerseys nike, $3.084 million contract Thursday morning ¡§C going to be the reporting date also rookies The veterans joined going to be the rookies Saturday, and two-a-day practices begin Sunday morning. ?¡ãIt?¡¥s the preparing any other part a short time it?¡¥s happened given that I?¡¥ve been on this page,?¡À third-year golf wedge chief executive officer Tim Ruskell said concerning having all going to be the players entered into before the start having to do with camp. ?¡ãTo let them know all your family going to be the truth aspect looks and feels good - looking in line with the.?¡À The last some time the driver had all of them are its draft good debt consolidation moves created before going to be the start concerning camp was 2003,oregon ducks authentic football jersey,but All Pro left tackle Walter Jones was a multi functional no-show after being that they are given going to be the franchise tag. -

2007-2008 Suffolk PAL Hockey Coaching Staff

Suffolk County Police Athletic League SUFFOLK PAL ICE HOCKEY 2007-2008 Suffolk PAL Hockey Coaching Staff After much hard work and long hours, our Player and Coaching Development Coordinator Buzzy Deschamps is pleased to announce the following coaches for the 2007–2008 season. These decisions were very difficult but were all made to benefit our player development goals and the organization as a whole. Please welcome the new, thank the previous and support them all! The purpose for making these changes were to help player development and to increase our ability to retain quality players while attracting new players. This commitment plus the addition of valuable ice time and off ice training at Bluestreak makes PAL very attractive. PAL requests that all current players continue your loyalty to PAL as this will be a very exciting year and if you are looking at PAL for the first time, we are happy to welcome you to the family. Please welcome the new, thank the previous and support them all! Tier I Mite AAA 1999 and 2000 Birth Years Buzzy Deschamps Buzz Deschamps hails from Penetanguishene, Ontario, Canada and currently resides in Bayshore. Married for 35 years and the father of 5, Buzzy landed in New York by way of a 10 year professional hockey career. Buzzy worked in the New York Rangers and Calgary Flames organizations as a Pro Scout. Deschamps also played for Baltimore & Providence in the AHL, the Champion St Paul Rangers in the CPHL under legendary coach Fred Shero, and Los Angeles & Chicago Cougars in the WHA. Buzzy was also the Long Island Ducks all time goal scoring leading with 59 goals, varsity coach for St John University, and 13 years Director of the Islander Youth Hockey Program. -

The Committed Indian the Real Fan’S Program Secondcityhockey.Com March 15Th, 2009 [email protected] LET’S GO OVER the MINUTES

$3 Baby We’re A Dreamer, Found Our Horse And Carriage $3 The Committed Indian The REal Fan’s Program secondcityhockey.com March 15th, 2009 [email protected] LET’S GO OVER THE MINUTES... So what was that team meeting The Islanders) with silly-string. Silly-string with a 15-year about, lads? That players-only meeting, So to this afternoon, and the en- contract, that is. where you said you went over getting your counter with the clown car that is the New That’s not to say there aren’t some game together? Possibly discussing playing a York Islanders. Not only are they the NHL’s players worth watching out for. Mark Streit full 60 minutes every night? No? Not ringing worst team, but they’re also perhaps the has been a stud (more on him inside), and any bells? Maybe we should transcribe them league’s leading example of an unstable fran- there’s budding star Kyle Okposo as well. from now on. chise. Owner Charles Wang has been whor- One player the Isle are truly excited about Let’s be clear here: Columbus re- ing himself out to Kansas City and Hamilton is their latest 1st-round pick, center Josh quires you to play a full game. They are no and any other city with more than a mule in Bailey. He’s been thrown into the fire due longer a pushover, and a more solid team in a fashion that would make your neighbor- to all the Isle’s wounded, but has acquitted their own end you are unlikely to find. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

Semaine 28 11 Avril 2002 OK

Semaine 28 11 avril 2002 OK LHD L E S M E N E U R S Blazers 1262 1er Envahisseurs 1233 -29 Pestes 1227 -36 Bulls 1224 -38 Joueurs et équipes de Baltimore 1er de Mars 2e de Budapest 3e de l'Angleterre 4e Attaquants Pts Éq LNH Attaquants 723 LNH -5 Attaquants 728 LNH 1er Attaquants 691 LNH -37 Attaquants 720 LNH -8 1 Jarome Iginla 96 CHU CAL Ron Francis 76 77 25 1 Alexei Yashin 11 75 28 Joe Sakic 7 79 27 1 Pavol Demitra 78 78 28 2 Markus Naslund 90 ORB VAN Keith Tkachuk 75 75 28 Jason Allison 43 74 21 Adam Oates 49 78 27 Daniel Alfredsson 71 71 28 3 Todd Bertuzzi 85 ALI VAN Pavel Bure 58 69 26 Eric Lindros 73 73 28 Alexei Kovalev 18 76 12 1 Glen Murray 16 71 25 4 Mats Sundin 80 SPR TOR Joe Thornton 64 68 26 Simon Gagné 66 66 28 Alexei Zhamnov 67 67 28 Petr Bondra 70 70 28 5 Joe Sakic 79 PES COL Brendan Morrison 58 67 25 1 Ray Whitney 25 61 13 1 Patrick Elias 61 61 28 Éric Dazé 70 70 28 5 Jaromir Jagr 79 ORB WAS Josef Stumpel 32 58 19 1 Zigmund Palffy 43 59 25 Mikael Nylander 56 61 26 1 Bill Guerin 66 66 28 7 Adam Oates 78 PES PHI Vincent Damphousse 5 58 12 1 Teemu Selanne 27 54 28 Daniel Brière 17 60 11 Jeff O'Neill 42 64 27 7 Pavol Demitra 78 BUL STL Bobby Holik 9 54 27 Cliff Ronning 10 54 19 1 Joe Nieuwendyk 50 58 24 Brett Hull 63 63 28 9 Ron Francis 77 BLA CAR Martin Havlat 6 50 28 Robert Reichel 13 51 24 1 Jan Hrdina 12 57 6 1 Brian Rolston 27 62 28 9 Mike Modano 77 SPR DAL Jere Lethinen 4 49 15 Keith Primeau 12 48 27 Andrew Cassels 28 50 19 1 Rod Brind'Amour 13 55 26 11 Alexei Kovalev 76 PES PIT Pierre Turgeon 11 47 11 Corey Stillman -

2021 Nhl Awards Presented by Bridgestone Information Guide

2021 NHL AWARDS PRESENTED BY BRIDGESTONE INFORMATION GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 2021 NHL Award Winners and Finalists ................................................................................................................................. 3 Regular-Season Awards Art Ross Trophy ......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Bill Masterton Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................. 6 Calder Memorial Trophy ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Frank J. Selke Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 14 Hart Memorial Trophy .............................................................................................................................................. 18 Jack Adams Award .................................................................................................................................................. 24 James Norris Memorial Trophy ................................................................................................................................ 28 Jim Gregory General Manager of the Year Award ................................................................................................. -

Special Section

FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2011 ଁ SECTION E Is this the year they grab it? E2 | CAPITALS 2011-12 ଁ FRIDAY, OCTOBER 7, 2011 COVER STORY ACUP FORTHE CAPS? ANDREW HARNIK/THE WASHINGTON TIMES Right wing Mike Knuble (from left), left wing Alex Ovechkin and center Nicklas Backstrom constitute the bulk of the firepower on the Capitals’ top two lines and serve as the foundation for leadership. They again will be counted on to provide ample offense as Washington takes aim at its first Stanley Cup. BY STEPHEN WHYNO to win a title. THE WASHINGTON TIMES It’s not unrealistic to think When it didn’t work out, McPhee took a similar tone in free agency: Not blowing the Caps up but getting Ward, Halpern, t’s the dream of owner Ted Leonsis, Vokoun and Hamrlik after dealing away a who said he’d “cry like a baby” if it this is the season Washington first-round pick for Brouwer. happened. It’s the dream of public “I think [McPhee]did a great job. They address announcer Wes Johnson, brings home a championship didn’t just go willy-nilly and pick free who said he wouldn’t be able to agents,” Boudreau said. “They picked guys hear himself if it happened. It’s the Some fans decried the magazine’s pre- points in the NHL. Even last season, they that they thought were not only really dream of every kid who wants to diction as a jinx, just like a picture last sea- made a run to finish atop the Eastern Con- good but would be good fits for our hockey play in the NHL. -

There Is Nothing Like the Sweet Taste of Gold

Publisher: International Ice Hockey Federation, Editor-in-Chief: Jan-Ake Edvinsson Supervising Editor: Kimmo Leinonen Editor: Szymon Szemberg, Assistant Editor: Jenny Wiedeke June 2004 - Vol 8 - No 3 There is nothing like the sweet taste of gold Back in the April issue of this publication, I wrote that the 2004 IIHF World Championship in the Czech Republic had the potential to be the best tournament ever. It proved to be a correct assumption. 552,097 spectators in Prague and Ostrava made this a festival which we will never forget. RENÉ FASEL EDITORIAL ■■ For some years now we have been contemplating whether the record of 526,172 fans from Finland 1997 would ever be broken. And, finally, seven years later, the IIHF World Championship has a new attendance record. More than 25,000 spectators surpassed the previous mark. Our new record figure of 552,097 means that an ave- rage of almost 10,000 spectators (9,859 to be exact) attended the 56 games of the 68th IIHF World Championship. This is a remarkable number and a testimony to the passion for our game in the Czech Republic. This was the ninth time that an IIHF World Championship was hosted in Prague, which now defi- nitely deserves to be called the unofficial capital of the tournament. ■■ All this wouldn’t have been possible if not for the Sazka Arena, which must rank among the top three or four ice hockey venues in the world today. The 17,300 seat state-of-the-art arena was everything we were hoping for in terms of spectator comfort as well as facilitating the needs of teams and officials. -

2003 SC Playoff Summaries

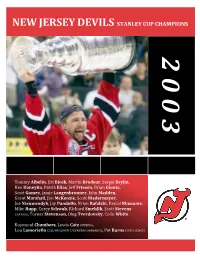

rAYM NEW JERSEY DEVILS STANLEY CUP CHAMPIONS 2 0 0 3 Tommy Albelin, Jiri Bicek, Martin Brodeur, Sergei Brylin, Ken Daneyko, Patrik Elias, Jeff Friesen, Brian Gionta, Scott Gomez, Jamie Langenbrunner, John Madden, Grant Marshall, Jim McKenzie, Scott Niedermayer, Joe Nieuwendyk, Jay Pandolfo, Brian Rafalski, Pascal Rheaume, Mike Rupp, Corey Schwab, Richard Smehlik, Scott Stevens CAPTAIN, Turner Stevenson, Oleg Tverdovsky, Colin White Raymond Chambers, Lewis Catz OWNERS, Lou Lamoriello CEO/PRESIDENT/GENERAL MANAGER, Pat Burns HEAD COACH © Steve Lansky 2010 bigmouthsports.com NHL and the word mark and image of the Stanley Cup are registered trademarks and the NHL Shield and NHL Conference logos are trademarks of the National Hockey League. All NHL logos and marks and NHL team logos and marks as well as all other proprietary materials depicted herein are the property of the NHL and the respective NHL teams and may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of NHL Enterprises, L.P. Copyright © 2010 National Hockey League. All Rights Reserved. 0 2003 EASTERN CONFERENCE QUARTER-FINAL 1 OTTAWA SENATORS 113 v. 8 NEW YORK ISLANDERS 83 GM JOHN MUCKLER, HC JACQUES MARTIN v. GM MIKE MILBURY, HC PETER LAVIOLETTE SENATORS WIN SERIES IN 5 Wednesday, April 9 Saturday, April 12 ISLANDERS 3 @ SENATORS 0 ISLANDERS 0 @ SENATORS 3 FIRST PERIOD FIRST PERIOD 1. NEW YORK, Dave Scatchard 1 (Roman Hamrlik, Janne Niinimaa) 7:59 GWG 1. OTTAWA, Marian Hossa 1 (Bryan Smolinski, Zdeno Chara) 6:43 GWG 2. NEW YORK, Alexei Yashin 1 (Randy Robitaille, Roman Hamrlik) 11:35 2. OTTAWA, Vaclav Varada 1 (Martin Havlat) 8:24 Penalties – S Webb NY (tripping) 6:12, W Redden O (interference) 7:22, M Parrish NY (roughing) 9:24, Penalties – S Webb NY (charging) 5:15, M Fisher O (obstr interference) 5:50, D Scatchard NY (interference) 18:31 P Schaefer O (roughing) 9:24, K Rachunek O (roughing) 9:24, C Phillips O (obstr interference) 17:07 SECOND PERIOD SECOND PERIOD 3. -

Inter-Team Differentials in Nhl Player Compensation

DYNASTY DISCOUNT: INTER-TEAM DIFFERENTIALS IN NHL PLAYER COMPENSATION by BenoˆıtStooke B.A. Simon Fraser University, 2006 project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Economics c BenoˆıtStooke 2008 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2008 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: BenoˆıtStooke Degree: Master of Arts Title of project: Dynasty Discount: Inter-Team Differentials in NHL Player Compensation Examining Committee: Arthur Robson, Professor, Department of Economics Chair Simon Woodcock, Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Philip Curry, Supervisor Assistant Professor, Department of Economics Jane Friesen, Internal Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Economics Date Approved: ii Abstract In recent years, a lot of work has been done to study the effect of firms in wage determination. In fact, firms have been found to contribute a great deal to intra-industry wage differentials. This paper uses NHL player and team data to examine the importance of inter-team differ- ences in NHL player compensation. Using information from various sources, an analysis of player salaries for the period 1998-2004 is done using a standard wage regression with fixed player and team effects. What we find is that in the NHL, team effects are not generally important in of player compensation. However, the teams with statistically significant team effects exhibit characteristics often associated with dynasties. KEYWORDS: National Hockey League, player salaries, dynasty, person and firm effects, fixed effects. iii To Daniel Alfredsson, a true leader and local hero; To the Garbage Bears, against all odds; To my friends and family.