Playing in the Sand with Picasso: Relief Sculpture As Game in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 14, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Chai Lee (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE HONORS 100-YEAR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PICASSO AND CHICAGO WITH LANDMARK MUSEUM–WIDE CELEBRATION First Large-Scale Picasso Exhibition Presented by the Art Institute in 30 Years Commemorates Centennial Anniversary of the Armory Show Picasso and Chicago on View Exclusively at the Art Institute February 20–May 12, 2013 Special Loans, Installations throughout Museum, and Programs Enhance Presentation This winter, the Art Institute of Chicago celebrates the unique relationship between Chicago and one of the preeminent artists of the 20th century—Pablo Picasso—with special presentations, singular paintings on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and programs throughout the museum befitting the artist’s unparalleled range and influence. The centerpiece of this celebration is the major exhibition Picasso and Chicago, on view from February 20 through May 12, 2013 in the Art Institute’s Regenstein Hall, which features more than 250 works selected from the museum’s own exceptional holdings and from private collections throughout Chicago. Representing Picasso’s innovations in nearly every media—paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, and ceramics—the works not only tell the story of Picasso’s artistic development but also the city’s great interest in and support for the artist since the Armory Show of 1913, a signal event in the history of modern art. BMO Harris is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago. "As Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago, and a bank deeply rooted in the Chicago community, we're pleased to support an exhibition highlighting the historic works of such a monumental artist while showcasing the artistic influence of the great city of Chicago," said Judy Rice, SVP Community Affairs & Government Relations, BMO Harris Bank. -

Friends of the Institute

FRIENDS OF THE INSTITUTE SEPTEMBER 2012 Lecture Bookmarks THE FITERMAN LECTURE SERIES | THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 13 | PILLSBURY AUDITORIUM, 11 A.M. are Here! Your 2012–2013 Fiterman Pablo Picasso in Vallauris: Lecture Series bookmark is enclosed. Mark your The Artist and the Artisans, 1954–1964 calendar! Luncheons follow the September, December, known, such as Toby Jelinek, Joseph-Marius Tiola, February, and May lectures. and Paul Massier. They participated in the creation of the sheet metal sculptures from 1954–1964 that marked the culmination of formal investiga- tions that had begun in Picasso’s earlier Cubist experiments. Diana Widmaier Picasso is an art historian currently living in New York City. After receiving a Master’s Degree in private law (University Paris-Assas) and a Master’s degree in Art History (University Paris-Sorbonne), she specialized in Old Master drawings. She worked on exhibitions at museums in New York (Metropolitan Museum) and Paris and later became an expert at Sotheby’s. Since 2003 she has been preparing a Catalogue Photograph © Rainer Hosch 2012 Raisonne of the sculptures of Pablo Picasso with Of the great art and artists of the twentieth century, a team of researchers. Widmaier Picasso recently the life and work of Pablo Picasso is perhaps most co-curated with John Richardson an exhibit at familiar. On Thursday, September 13, the Friends Gagosian Gallery in New York called Picasso and are honored to present Diana Widmaier Picasso, Marie-Therese: l’Amour Fou. She is the author of granddaughter of Picasso and Marie-Therese Picasso: Art Can Only be Erotic and several essays Walter, who will tell us a story about Picasso on the work of Picasso. -

The Rutting Bull by Jerry Saltz New York April 24, 2011

New York Magazine April 24 2011 G AGOSIAN GALLERY The Rutting Bull An exhibition devoted to Picasso and a mistress-muse is soaked in sex. By Jerry Saltz All artwork 2011 estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York ‘Picasso and Marie-Thérèse: L’Amour fou,” the rapturous, vagino-maniacal show of more than 80 Pablo Picasso works at Gagosian, is a love story. It tells a tale of a devouring monster, a goddess and doormat, frenzied sex, and abject cruelty. The woman of the show’s title is Marie-Thérèse Walter, called “the greatest sexual passion of Picasso’s life,” “endlessly submissive and willing,” the sumptuous voluptuary who surrendered to his sadomasochistic demands. He himself once called her “a slice of melon,” and she said of herself, “I always cried with Picasso. I bowed my head in front of him.” “L’Amour fou” was curated by John Richardson and Diana Widmaier Picasso, granddaughter of the artist and Marie-Thérèse. Widmaier Picasso once told a British paper that her grandmother talked of their “secrets,” some of which have been widely reported. Richardson (in his acclaimed three-part Picasso biography) says that Picasso enjoyed “the perverse pleasure of denying [Walter] the release of orgasm.” Yet Walter herself rhapsodized, many years later, that sex with Picasso was “completely fulfilling,” describing him as “very virile.” For decades, no one knew of Walter or that she was Picasso’s mistress from 1927 until around 1937. Not only was she his submissive sexual conquest, artistic muse, psychic victim, and mother of his daughter; she’s the fleshy subject of some of his juiciest paintings. -

Boisgeloup, L'atelier Normand De Picasso

DOSSIER DE PRESSE UNE SAISON PICASSO ROUEN 1ER AVRIL / 11 SEPTEMBRE 2017 MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS Boisgeloup, l’atelier normand de Picasso saisonpicassorouen.fr / ticketmaster.fr PICASSO, CE NORMAND… Peu de gens le savent, Picasso a résidé et travaillé pendant cinq années en Normandie, dans son château de Boisgeloup, près de Gisors. Jusqu’ici, aucun ouvrage, aucune exposition n’avaient été consacrés à cette période intensément créative, qui s’étend de 1930 à 1935, et voit Picasso pratiquer particulièrement la sculpture, mais aussi la peinture, le dessin, la gravure, la photographie avant de s’adonner à l’écriture. La Normandie, par ailleurs, n’avait encore jamais accueilli une exposition signifcative dédiée au grand maître du XXe siècle. Pour réparer ces lacunes, nous avons imaginé une véritable Saison Picasso, et réuni les meilleurs partenaires pour déployer pas moins de trois expositions dans autant de musées différents. Le musée national Picasso-Paris, le Centre Pompidou et le Musée national d’art moderne, Le musée Picasso Antibes, la Fundación Almine y Bernard para el Arte, Picasso Administration et les collectionneurs particuliers, le Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster et de nombreux autres musées, sont réunis dans ce projet. Invitation à découvrir les multiples facettes d’un génie en perpétuelle métamorphose, mais aussi de le percevoir dans sa relation avec l’histoire des arts et des techniques, au sein des extraordinaires collections de la Réunion des Musées Métropolitains. En s’installant en Normandie, Picasso ne marchait-il pas sur -

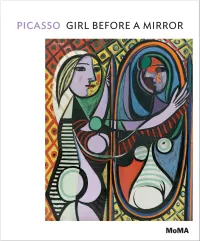

Picasso: Girl Before a Mirror

PICASSO GIRL BEFORE A MIRROR ANNE UMLAND THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK At some point on Wednesday, March 14, 1932, Pablo Picasso stepped back from his easel and took a long, hard look at the painting we know as Girl before a Mirror. Deciding there was nothing more he wanted to change or to add, he recorded the day, month, and year of completion on the back of the canvas and signed it on the front, in white paint, up in the picture’s top-left corner.1 Riotous in color and chockablock with pattern, this image of a young woman and her mirror reflection was finished toward the end of a grand series of can- vases the artist had begun in December 1931, three months before.2 Its jewel tones and compartmentalized composition, with discrete areas of luminous color bounded by lines, have prompted many viewers to compare its visual effect to that of stained glass or cloisonné enamel. To draw close to the painting and scrutinize its surface, however, is to discover that, unlike colored glass, Girl before a Mirror is densely opaque, rife with clotted passages and made up of multiple complex layers, evidence of its having been worked and reworked. The subject of this painting, too, is complex and filled with contradictory symbols. The art historian Robert Rosenblum memorably described the girl’s face, at left, a smoothly painted, delicately blushing pink-lavender profile com- bined with a heavily built-up, garishly colored yellow-and-red frontal view, as “a marvel of compression” containing within itself allusions to youth and old age, sun and moon, light and shadow, and “merging . -

MUSEUM ART Winter Issue 2019

& MUSEUM ART Winter Issue 2019 SPECTRUM MIAMI & RED DOT MIAMI Security. Integrity. Discretion. STORAGE MOVING SHIPPING INSTALLATION London | Paris | Côte d’Azur | New York | Los Angeles | Miami | Chicago | Dubai +44 (0) 208 023 6540 [email protected] www.cadogantate.com 47059 LEX Cadogan Tate A4 Page Advert V2.indd 1 17/06/2019 15:18 CONTENTS 12 ART DUE DILIGENCE PANEL 14 The Ritossa Family Office Summit Dubai under the patronage of Sheikh Ahmed Al Maktoum ART ON BOARD Art on board Superyachts 04 24 SPECTRUM MIAMI & RED DOT MIAMI Modigliani and His Muses Cover image: Artblend - Timothy Rives Rash II CEO & Editor Siruli Studio WELCOME Modigliani Institute in Korea ART & MUSEUM Magazine and will also appear at many of the largest finance, banking and Family MAGAZINE Office Events around the World. Welcome to Art & Museum Magazine. This Media Kit. - www.ourmediakit.co.uk publication is a supplement for Family Office Magazine, the only publication in the world We recently formed several strategic dedicated to the Family Office space. We have partnerships with organisations including 16 a readership of over 46,000 comprising of some The British Art Fair and Russian Art of the wealthiest people in the world and their Week. Prior to this we have attended and advisors. Many have a keen interest in the arts, covered many other international art fairs some are connoisseurs and other are investors. and exhibitions for our other publications. Many people do not understand the role of We are very receptive to new ideas for a Family Office. This is traditionally a private stories and editorials. -

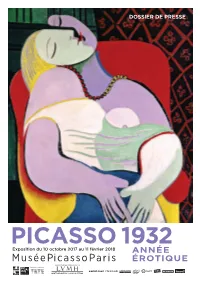

DP Picasso1932 Web FR.Pdf

2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE Du 10 octobre 2017 au 11 février 2018 au Musée national Picasso-Paris, grâce au soutien de LVMH/Moët Hennessy - Louis Vuitton Picasso 1932. Année érotique est la première exposition dédiée à une année de création entière chez Picasso, allant du 1er janvier au 31 décembre dune même année. Lexposition présentera des chefs-duvre essentiels dans la carrière de Picasso comme Le Rêve (huile sur toile, collection particulière) et de nombreux documents darchives replaçant les créations de cette année dans leur contexte. Cet événement, organisé en partenariat avec la Tate Modern de Londres, fait le pari dinviter le visiteur à suivre au quotidien, dans un parcours rigoureusement chronologique, la production dune année particulièrement riche. Il questionnera la célèbre formule de lartiste selon laquelle « luvre que lon fait est une façon de tenir son journal », qui sous-entend lidée dune coïncidence entre vie et création. Parmi les jalons de cette année exceptionnelle se trouvent les séries des baigneuses et les portraits et compositions colorées autour de la figure de Marie-Thérèse Walter, posant la question du rapport au surréalisme. En parallèle de ces uvres sensuelles et érotiques, lartiste revient au thème de la Crucifixion, tandis que Brassaï réalise en décembre un reportage photographique dans son atelier de Boisgeloup. 1932 voit également la « muséification » de luvre de Picasso à travers lorganisation des rétrospectives à la galerie Georges Petit à Paris et au Kunsthaus de Zurich qui exposent, pour la première fois depuis 1911, le peintre espagnol au public et aux critiques. Lannée est enfin marquée par la parution du premier volume du Catalogue raisonné de luvre de Pablo Picasso, publié par Christian Zervos, qui place lauteur des Demoiselles dAvignon dans une exploration de son propre travail. -

Read Dialogues with Japanese Art, Text From

DIALOGUES WITH JAPANESE ART Malén Gual Is there a connection to be found between Picasso and the art of East Asia? Were Japanese prints as important to Picasso as African and Oceanic sculptures and masks, commonly known as ‘Negro art’? Did the artist study the canon of Japanese engravings with the same careful attention he paid to classical archaism? Did he assimilate Oriental teachings in the same way that he absorbed the lessons of the French and Spanish pictorial tradition? Since the early 20th century, many pages and many exhibitions have been devoted to analysing the different influences which came to bear on Picasso and his dialogue with earlier generations of artists,1 but his relationship with Japonism has been either ignored or mentioned only in passing.2 Viewed as a whole, Picasso’s œuvre is far removed from that of the Japanese masters; the vitality and rhythm of his work, his frequent changes of style, and the ways in which his models are metamorphosed are quite unlike the static harmony and repetition of Oriental art. What’s more, Picasso himself told Guillaume Apollinaire how little he cared for this artistic phenomenon. ‘I hasten to add, however, that I detest exoticism. I’ve never liked the Chinese, the Japanese or the Persians.’3 All of the above might discourage any search for connections between the Malaga- born artist and the masters of the Edo period. But a number of factors suggest that Picasso had a solid acquaintance with the Japanese engravers’ methods and a profound admiration for their work. (fig. -

A Granddaughter's Picasso Album

The Wall Street Journal May 21 2011 GAGOSIAN GALLERY ICONS MAY 21, 2011 A Granddaughter's Picasso Album By KELLY CROW Growing up, Diana Widmaier Picasso heard stories galore about her grandfather, Pablo Picasso, but she learned little about her grandmother, Marie-Thérèse Walter. This much she—and the art world—knew: The artist was 45 years old and miserable in his marriage to a Russian ballerina when he spotted Ms. Walter, then 17, outside a Parisian department store in 1927. Picasso quickly wooed the girl, and for the next 14 years the couple carried on a semisecret love affair that produced a daughter, Maya, and inspired some of the artist's best-known paintings and sculptures. (Last spring, a Picasso nude of Ms. Walter sold for $106.5 million—the most ever for an auctioned artwork.) Copyright Estate of Pablo Picasso/ARS, NY/Gagosian Gallery 'Marie-Thérèse in a Red Beret and Fur Collar,' at the Gagosian show. Since Picasso never spoke publicly about Ms. Walter, his descendants felt duty-bound to follow suit—that is, until a year ago when Ms. Widmaier Picasso, a lawyer-turned-art-scholar now living in New York, convinced her mother, Maya, to open up. Out came boxes of family archives brimming with rarely seen artworks, love letters and photos. Now, Ms. Widmaier Picasso and the artist's biographer, John Richardson, are exhibiting a trove of this fresh material in a show, "Picasso and Marie-Thérèse: L'amour Fou," on view at New York's Gagosian Gallery until July 15. Gallery director Valentina Castellani said seven museums also lent pieces to the show, while some others are for sale by the Picasso estate. -

Dossier De Presse Picasso Les Années Vallauris

dossier de presse Picasso Les années Vallauris 23 juin - 22 octobre 2018 Vallauris > Côte d’Azur Musée national Pablo Picasso, La Guerre et la Paix Musée Magnelli, musée de la céramique Eden Madoura, lieu d’Art, d’Histoire et de Création communiqué p.3 press release p.5 comunicato stampa p.7 textes des salles p.9 parcours de l’exposition dans la ville p.13 intention scénographique p.14 chronologie p.15 liste des œuvres exposées p.16 extraits du catalogue de l’exposition p.40 catalogue de l’exposition p.52 programmation culturelle p.54 Musée national Pablo Picasso, La Guerre et la Paix p.56 Musée Magnelli, musée de la céramique p.57 Eden p.58 Madoura, lieu d’Art, d’Histoire et de Création p.59 Nérolium p.60 informations pratiques p.61 visuels disponibles pour la presse p.62 partenaires médias p.68 communiqué Picasso Les années Vallauris 23 juin - 22 octobre 2018 Vallauris > Côte d’Azur Musée national Pablo Picasso, La Guerre et la Paix Musée Magnelli, musée de la céramique Eden Madoura, lieu d’Art, d’Histoire et de Création Cette exposition est organisée par la Ville de Vallauris – Golfe Juan, les Musées du XXe siècle des Alpes Maritimes et la Réunion des Musées Nationaux- Grand Palais Organisée dans le cadre de « Picasso-Méditerranée », l’exposition « Picasso, les années Vallauris » explore, au cœur de Vallauris, dans les lieux mêmes où l’artiste a vécu et travaillé de 1947 à 1955, la vie et l’œuvre de Picasso depuis son installation dans la ville provençale, à la villa « La Galloise », jusqu’à son départ pour Cannes. -

Authenticating Picasso – Art News

AUTHENTICATION IN ART Art News Service Authenticating Picasso BY George Stolz POSTED 2/01/13 Forty years after Picasso’s death, while his paintings are among the most expensive ever sold, the problem of how to authenticate his work remains a challenge. To avoid mistakes, four of his five surviving heirs have clarified the process but have not included his elder daughter Picasso could be capricious when it came to authenticating his own work. On one occasion, he refused to sign a canvas he knew he had painted, saying, “I can paint false Picassos just as well as anybody.” On another, he refused to sign an authentic painting, explaining to the woman who had brought it to him, “If I sign it now, I’ll be putting my 1943 signature on a canvas painted in 1922. No, I cannot sign it, madam, I’m sorry.” And on yet another occasion, an irked Picasso angrily covered a work brought to him for authentication with so many The 33-volume catalogue of Picasso’s work by Christian Zervos. signatures that he defaced and effectively ruined it. CHRISTIE’S IMAGES LTD. 2012 Even today, 40 years after Picasso’s death, the question of how his heirs exercise their right under French law to authenticate his work is a knotty one. Picasso was, by some estimates, one of the wealthiest men in the world when he died, in 1973. In the early 1980s, after years of legal wrangling and well-publicized squabbling over the settlement of his estate, his heirs established a committee to officially authenticate his works. -

Dossier De Presse Une Saison Picasso Rouen 1Er Avril / 11 Septembre 2017

DOSSIER DE PRESSE UNE SAISON PICASSO ROUEN 1ER AVRIL / 11 SEPTEMBRE 2017 MUSÉE DE LA CÉRAMIQUE Picasso : sculptures céramiques saisonpicassorouen.fr / ticketmaster.fr PICASSO, CE NORMAND… Peu de gens le savent, Picasso a résidé et travaillé pendant cinq années en Normandie, dans son château de Boisgeloup, près de Gisors. Jusqu’ici, aucun ouvrage, aucune exposition n’avaient été consacrés à cette période intensément créative, qui s’étend de 1930 à 1935, et voit Picasso pratiquer particulièrement la sculpture, mais aussi la peinture, le dessin, la gravure, la photographie avant de s’adonner à l’écriture. La Normandie, par ailleurs, n’avait encore jamais accueilli une exposition significative dédiée au grand maître du XXe siècle. Pour réparer ces lacunes, nous avons imaginé une véritable Saison Picasso, et réuni les meilleurs partenaires pour déployer pas moins de trois expositions dans autant de musées différents. Le musée national Picasso-Paris, le Centre Pompidou et le Musée national d’art moderne, Le musée Picasso Antibes, la Fundación Almine y Bernard para el Arte, Picasso Administration et les collectionneurs particuliers, le Kunstmuseum Pablo Picasso Münster et de nombreux autres musées, sont réunis dans ce projet. Invitation à découvrir les multiples facettes d’un génie en perpétuelle métamorphose, mais aussi de le percevoir dans sa relation avec l’histoire des arts et des techniques, au sein des extraordinaires collections de la Réunion des Musées Métropolitains. En s’installant en Normandie, Picasso ne marchait-il pas sur les traces