The Battle for Picasso's Multi- Billion-Dollar Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Ballet De Parade De Picasso Y Su Papel En La Estética Cubista De La Galería De L’Effort Moderne

El ballet de Parade de Picasso y su papel en la estética cubista de la galería de L’Effort Moderne Belén Atencia Conde-Pumpido Universidad de Málaga [email protected] RESUMEN: Tras el estallido de la Primera Guerra Mundial, los artistas parecen haberse alejado de la estética cubista en pos de un clasicis- mo más acorde con la situación político-social del momento. Sin embargo, Léonce Rosenberg aglutinará a una serie de artistas cubistas en torno a una nueva galería, L’Effort Moderne, la cual aún no es conocida ni por el gran público ni por los críticos de arte. En este contexto, y de manera independiente a la galería de Rosenberg, Picasso presenta su último trabajo: los decorados de Parade, realizados para el empresario de ballets rusos Serge Diaghilev y con una decidida estética cubista que beneficiará, sin pretenderlo, la propaganda orquestada por Rosenberg para la inauguración de su galería. PALABRAS CLAVE: Cubismo, Parade, Picasso, Léonce Rosenberg, Diseños, L’Effort Moderne. The Ballet of Parade and its Significations in Cubism Aesthetic of the Galerie L’Effort Moderne ABSTRACT: After the outbreak of the First World War, the artists seem to step away from the cubist aesthetic toward a classicist style which better reflected the socio-political situation at the time. However, Léonce Rosenberg gathers a series of cubist artists around a new gallery, L’Effort Moderne, which is not yet acknowledged by the general public, nor by the art critics. In this context and independently from Rosen- berg’s gallery, Picasso presents his last work: the set designs for Parade made for the Russian ballet impresario Serge Diaghliev and with a decided cubist aesthetic that will unintentionally benefit Rosenberg’s propaganda for the opening of his gallery. -

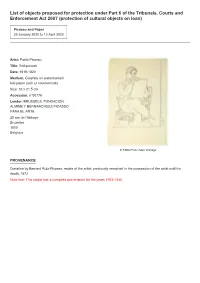

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Self-portrait Date: 1918-1920 Medium: Graphite on watermarked laid paper (with LI countermark) Size: 32 x 21.5 cm Accession: n°00776 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Mother with a Child Sitting on her Lap Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum (with irregular pattern). Invitation card printed on the back Size: 13.8 x 10 cm Accession: n°11684 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; Estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object was made post-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Little Girl Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum. -

Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire

H-France Review Volume 9 (2009) Page 355 H-France Review Vol. 9 (June 2009), No. 86 Peter Read, Picasso and Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory (Ahmanson-Murphy Fine Arts Books). University of California Press: Berkeley, 2008. 334 pp. + illustrations. $49.95 (hb). ISBN 052-0243- 617. Review by John Finlay, Independent Scholar. Peter Read’s Picasso et Apollinaire: Métamorphoses de la memoire 1905/1973 was first published in France in 1995 and is now translated into English, revised, updated and developed incorporating the author’s most recent publications on both Picasso and Apollinaire. Picasso & Apollinaire: The Persistence of Memory also uses indispensable material drawn from pioneering studies on Picasso’s sculptures, sketchbooks and recent publications by eminent scholars such as Elizabeth Cowling, Anne Baldassari, Michael Fitzgerald, Christina Lichtenstern, William Rubin, John Richardson and Werner Spies as well as a number of other seminal texts for both art historian and student.[1] Although much of Apollinaire’s poetic and literary work has now been published in French it remains largely untranslated, and Read’s scholarly deciphering using the original texts is astonishing, daring and enlightening to the Picasso scholar and reader of the French language.[2] Divided into three parts and progressing chronologically through Picasso’s art and friendship with Apollinaire, the first section astutely analyses the early years from first encounters, Picasso’s portraits of Apollinaire, shared literary and artistic interests, the birth of Cubism, the poet’s writings on the artist, sketches, poems and “primitive art,” World War I, through to the final months before Apollinaire’s death from influenza on 9 November 1918. -

Artist Resources – Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) Musée Picasso, Paris Picasso at Moma

Artist Resources – Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973) Musée Picasso, Paris Picasso at MoMA Picasso talks Communism, visual perception, and inspiration in this intimate interview at his home in Cannes in 1957. “My work is a constructive one. I am Building, not tearing down. What people call deformation in my work results from their own misapprehension. It's not a matter of deformation; it's a question of formation. My work oBeys laws I have spent my life in formulating and adhering to. EveryBody has a different idea of what constitutes reality and the suBstance of things….I set [oBjects] down in what my intellect tells me is the order and form in which they appear to me.” In these excerpts from 1943, from his Book, Conversations with Picasso, French photographer and sculpture Brassaï reflects candidly with his friend and contemporary aBout Building on the past, authenticity, and gathering inspiration from nature, history, and museums. “I thought I learned a lot from him. Mostly in terms of the way he worked, the concentration in which he worked, the unity of spirit in thinking in thinking aBout nothing else, giving everything away for that,” reflected Françoise Gilot in an interview with Charlie Rose in 1998. In 2019, she puBlished the groundBreaking memoir of her own life as an artist and her relationship with the untamaBle master, Life with Picasso. MoMA’s monumental 1996 exhiBition Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation emBarked on a Picasso in his Montmartre studio, 1908 tour of over 200 visual representations By the artist of his friends, family, and contemporaries. -

(312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 14, 2013 MEDIA CONTACTS: Erin Hogan Chai Lee (312) 443-3664 (312) 443-3625 [email protected] [email protected] THE ART INSTITUTE HONORS 100-YEAR RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PICASSO AND CHICAGO WITH LANDMARK MUSEUM–WIDE CELEBRATION First Large-Scale Picasso Exhibition Presented by the Art Institute in 30 Years Commemorates Centennial Anniversary of the Armory Show Picasso and Chicago on View Exclusively at the Art Institute February 20–May 12, 2013 Special Loans, Installations throughout Museum, and Programs Enhance Presentation This winter, the Art Institute of Chicago celebrates the unique relationship between Chicago and one of the preeminent artists of the 20th century—Pablo Picasso—with special presentations, singular paintings on loan from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and programs throughout the museum befitting the artist’s unparalleled range and influence. The centerpiece of this celebration is the major exhibition Picasso and Chicago, on view from February 20 through May 12, 2013 in the Art Institute’s Regenstein Hall, which features more than 250 works selected from the museum’s own exceptional holdings and from private collections throughout Chicago. Representing Picasso’s innovations in nearly every media—paintings, sculpture, prints, drawings, and ceramics—the works not only tell the story of Picasso’s artistic development but also the city’s great interest in and support for the artist since the Armory Show of 1913, a signal event in the history of modern art. BMO Harris is the Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago. "As Lead Corporate Sponsor of Picasso and Chicago, and a bank deeply rooted in the Chicago community, we're pleased to support an exhibition highlighting the historic works of such a monumental artist while showcasing the artistic influence of the great city of Chicago," said Judy Rice, SVP Community Affairs & Government Relations, BMO Harris Bank. -

Programming; Providing an Environment for the Growth and Education of Theatre Professionals, Audiences, and the Community at Large

JULY 2017 WELCOME MIKE HAUSBERG Welcome to The Old Globe and this production of King Richard II. Our goal is to serve all of San Diego and beyond through the art of theatre. Below are the mission and values that drive our work. We thank you for being a crucial part of what we do. MISSION STATEMENT The mission of The Old Globe is to preserve, strengthen, and advance American theatre by: creating theatrical experiences of the highest professional standards; producing and presenting works of exceptional merit, designed to reach current and future audiences; ensuring diversity and balance in programming; providing an environment for the growth and education of theatre professionals, audiences, and the community at large. STATEMENT OF VALUES The Old Globe believes that theatre matters. Our commitment is to make it matter to more people. The values that shape this commitment are: TRANSFORMATION Theatre cultivates imagination and empathy, enriching our humanity and connecting us to each other by bringing us entertaining experiences, new ideas, and a wide range of stories told from many perspectives. INCLUSION The communities of San Diego, in their diversity and their commonality, are welcome and reflected at the Globe. Access for all to our stages and programs expands when we engage audiences in many ways and in many places. EXCELLENCE Our dedication to creating exceptional work demands a high standard of achievement in everything we do, on and off the stage. STABILITY Our priority every day is to steward a vital, nurturing, and financially secure institution that will thrive for generations. IMPACT Our prominence nationally and locally brings with it a responsibility to listen, collaborate, and act with integrity in order to serve. -

PICASSO Les Livres D’Artiste E T Tis R a D’ S Vre Li S Le PICASSO

PICASSO LES LIVRES d’ARTISTE The collection of Mr. A*** collection ofThe Mr. d’artiste livres Les PICASSO PICASSO Les livres d’artiste The collection of Mr. A*** Author’s note Years ago, at the University of Washington, I had the opportunity to teach a class on the ”Late Picasso.” For a specialist in nineteenth-century art, this was a particularly exciting and daunting opportunity, and one that would prove formative to my thinking about art’s history. Picasso does not allow for temporalization the way many other artists do: his late works harken back to old masterpieces just as his early works are themselves masterpieces before their time, and the many years of his long career comprise a host of “periods” overlapping and quoting one another in a form of historico-cubist play that is particularly Picassian itself. Picasso’s ability to engage the art-historical canon in new and complex ways was in no small part influenced by his collaborative projects. It is thus with great joy that I return to the varied treasures that constitute the artist’s immense creative output, this time from the perspective of his livres d’artiste, works singularly able to point up his transcendence across time, media, and culture. It is a joy and a privilege to be able to work with such an incredible collection, and I am very grateful to Mr. A***, and to Umberto Pregliasco and Filippo Rotundo for the opportunity to contribute to this fascinating project. The writing of this catalogue is indebted to the work of Sebastian Goeppert, Herma Goeppert-Frank, and Patrick Cramer, whose Pablo Picasso. -

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Jean-Marc Delvaux

JEAN-MARC DELVAUX LUNDI 21 NOVEMBRE 2016 Ventes futures 293 MERCREDI 30 NOVEMBRE, DROUOT SALLE 7. CHASSE, ART ÉQUESTRE, MILITARIA, DÉCORATIONS MILITAIRES, SOLDATS DE PLOMB, TAXIDERMIE, FAÏENCES des XVIIème, XVIIIème et XIXème siècles. 298 295 294 LUNDI 5, MARDI 6 et MERCREDI 7 DECEMBRE, DROUOT SALLE 2. BIJOUX, ARGENTERIE, ARGENTERIE RUSSE, COLLECTION D’ICÔNES. LUNDI 12 DECEMBRE, DROUOT EXTREME-ORIENT 297 296 VENDREDI 16 DECEMBRE, DROUOT CONDITIONS DE VENTE SALLES 5 et 6. La vente sera faite expressément au comptant. TABLEAUX ANCIENS ET MODERNES, Aucune réclamation ne sera recevable dès l’adjudication prononcée, les expositions successives ayant permis aux acquéreurs de constater l’état des objets présentés. DESSINS ANCIENS, L’adjudicataire sera le plus offrant et dernier enchérisseur, et aura pour obligation de remettre ses nom et adresse. MOBILIER ET OBJETS D’ART. Il devra acquitter, en sus du montant de l’enchère, par lot, les frais et taxes suivants : - pour les lots volontaires : 25,20% TTC. - pour les lots judiciaires, précédés d’un astérisque : 14,40% TTC. Dès l’adjudication prononcée, les achats sont sous l’entière responsabilité de l’adjudicataire. Aucun lot ne sera remis aux acquéreurs avant acquittement de l’intégralité des sommes dues. Les acquéreurs pourront obtenir tous renseignements concernant la livraison et l’expédition de leurs achats à la n de la vente. En cas de contestation au moment des adjudications, c’est-à-dire s’il est établi que deux ou plusieurs enchérisseurs ont simultanément porté une enchère équivalente, soit à haute voix, soit par signe, et réclament en même temps cet objet après le prononcé du mot “adjugé”, le-dit objet sera immédiatement remis en adjudication au prix proposé par les enchérisseurs et tout le public présent sera admis à enchérir à nouveau. -

Montmartre the Tour: La Place Des Abbesses (The Abbesses Square), the Small Streets, La Place Du Tertre (The Tertre Square), Le Sacré-Coeur (The Sacred Heart)

MONTMARTRE THE TOUR: LA PLACE DES ABBESSES (THE ABBESSES SQUARE), THE SMALL STREETS, LA PLACE DU TERTRE (THE TERTRE SQUARE), LE SACRÉ-COEUR (THE SACRED HEART) LE SACRÉ-COEUR THE SMALL STREETS LA PLACE DU TERTRE LES ABBESSES Lenght: Means of locomotion: on foot - 3H00 walking, Access for persons with reduced - half a day: walking + visit of the mobility : no Sacré-Coeur, Total distance: 4km - the entire day: walking + visit of Starting point: Place des Abbesses the Sacré-Coeur, the Montmartre (metro line 12, Abbesses station, museum and the Dali area. or the Montmartrobus Abbesses station) Public: All restaurant, « Le Relais de la Butte » (The Mound Inn), once called « Chez Azon » (At Azon’s). At the beginning of the 20th century, Father Azon gladly welcomed and fed all the penniless artists from the bateau- lavoir who paid him with works of art... which did not prevent him from Take rue des Abbesses going bankrupt ! (Abbesses Street) on your right and keep going forward for about 50 Climb the steps of this Emile metres. Goudeau small square (ex Ravignan Square). It is the same quietness At the Abbesses passage entrance, impression that we found in the on your right, graffities, drawings, Place des Abbesses, with benches, stencils and other inlays are trees, the big Wallace fountain, and animating the walls. some funny graffities. Pay close attention, you will have the opportunity to see many others On your left, with your back turned throughout the walk. to the steps, stands a recently cleaned building with white blinds Carry on and take rue Ravignan and green doors is the famous (Ravignan Street) on your right. -

Janet Hawley 2012 Design Copyright © the Slattery Media Group Pty Ltd 2012 First Published by the Slattery Media Group Pty Ltd 2012 All Rights Reserved

JANET H AWL EY ARTISTS IN CONVERSATION The Slattery Media Group Pty Ltd 1 Albert St, Richmond JANET Victoria, Australia, 3121 Text copyright © Janet Hawley 2012 Design copyright © The Slattery Media Group Pty Ltd 2012 First published by The Slattery Media Group Pty Ltd 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval H AWLEY system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the copyright owner. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. ARTISTS IN Portions of the work have been previously published in The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald’s Good Weekend and Sydney magazines, as well as Encounters with Australian Artists by Janet Hawley CONVERSATION (published by University of Queensland Press, 1993) Extracts from Donald Friend’s diaries: © Trustees of the Estate of Late Donald Friend (reproduced with permission from the Estate of the Late Donald Friend) All images and artworks used with permission. See images for credit information. Image on dust jacket of Janet Hawley © Graham Jepson National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Hawley, Janet, 1944 Title: Artists in conversation / Janet Hawley. ISBN: 9781921778735 (hbk.) Subjects: Artists–Australia–Anecdotes. Art, Modern. Dewey Number: 709.94 Group Publisher: Geoff Slattery Editor: Nancy Ianni Image research: Gemma Jungwirth Cover and page design: Kate Slattery Creative Director: Guy Shield Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin slatterymedia.com visit slatterymedia.com For Kimberley, ben, Sam and PhiliP JANET HAWLEY ARTISTS IN CONVERSATION ContentS Introduction ��������������������������������������������������������������� 9 1. Françoise Gilot ............................ 15 17. John Wolseley ..............................