La Comida Y Las Memorias: Food, Positionality, and the Problematics of Making One's Home

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

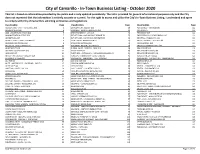

In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This List Is Based on Informa�On Provided by the Public and Is Only Updated Periodically

City of Camarillo - In-Town Business Listing - October 2020 This list is based on informaon provided by the public and is only updated periodically. The list is provided for general informaonal purposes only and the City does not represent that the informaon is enrely accurate or current. For the right to access and ulize the City's In-Town Business Lisng, I understand and agree to comply with City of Camarillo's soliciting ordinances and regulations. Classification Page Classification Page Classification Page ACCOUNTING - CPA - TAX SERVICE (93) 2 EMPLOYMENT AGENCY (10) 69 PET SERVICE - TRAINER (39) 112 ACUPUNCTURE (13) 4 ENGINEER - ENGINEERING SVCS (34) 70 PET STORE (7) 113 ADD- LOCATION/BUSINESS (64) 5 ENTERTAINMENT - LIVE (17) 71 PHARMACY (13) 114 ADMINISTRATION OFFICE (53) 7 ESTHETICIAN - HAS MASSAGE PERMIT (2) 72 PHOTOGRAPHY / VIDEOGRAPHY (10) 114 ADVERTISING (14) 8 ESTHETICIAN - NO MASSAGE PERMIT (35) 72 PRINTING - PUBLISHING (25) 114 AGRICULTURE - FARM - GROWER (5) 9 FILM - MOVIE PRODUCTION (2) 73 PRIVATE PATROL - SECURITY (4) 115 ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE (16) 9 FINANCIAL SERVICES (44) 73 PROFESSIONAL (33) 115 ANTIQUES - COLLECTIBLES (18) 10 FIREARMS - REPAIR / NO SALES (2) 74 PROPERTY MANAGEMENT (39) 117 APARTMENTS (36) 10 FLORAL-SALES - DESIGNS - GRW (10) 74 REAL ESTATE (18) 118 APPAREL - ACCESSORIES (94) 12 FOOD STORE (43) 75 REAL ESTATE AGENT (180) 118 APPRAISER (7) 14 FORTUNES - ASTROLOGY - HYPNOSIS(NON-MED) (3) 76 REAL ESTATE BROKER (31) 124 ARTIST - ART DEALER - GALLERY (32) 15 FUNERAL - CREMATORY - CEMETERIES (2) 76 REAL ESTATE -

Licensee List

UTAH DEPARTMENT OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGE CONTROL Current As Of Licenses by County, DBA Tuesday, September 28, 2021 License Types AL - AIRPORT LOUNGE AR - ARENA LICENSE BC - BANQUET CATERING BE - ON PREMISE BEER BR - BREWER LOCATED OUTSIDE UTAH BW - BEER WHOLESALER CL - BAR ESTABLISHMENT HA - HOSPITALITY AMENITY HC - HEALTH CARE FACILITY HL - HOTEL IN - INDUSTRIAL / MANUFACTURING LB - BAR ESTABLISHMENT LR - RESTAURANT FULL SERVICE LT - LIQUOR TRANSPORT LICENSE LW - LIQUOR WAREHOUSE MB - MANUFACTURING - BREWERY MD - MANUFACTURING - DISTILLERY MO - MASTER OFF PREMISE BEER RETAILER LICENSEMP - MINOR PERMIT/CONCERT-DANCE HALL MR - MANUFACTURER REPRESENTATIVE MW - MANUFACTURING - WINERY OP - OFF PREMISE BEER RETAILER PA - PACKAGE AGENCY PS - PUBLIC SERVICE RB - RESTAURANT/ BEER ONLY RC - RECEPTION CENTER RE - RESTAURANT RL - RESTAURANT LIMITED RS - RESORT SA - RELIGIOUS SC - SCIENTIFIC / EDUCATIONAL SE - SINGLE EVENT TB - TEMPORARY BEER TV - TAVERN - ON PREMISE BEER UNIDENTIFIED COUNTY - (93 Licenses) LICENSE DBA LOCATION ADDRESS CITY ST ZIP COUNTY PHONE BR00192 10 BARREL BREWING, LLC 62970 NE 18TH ST BEND OR 97701 602-396-0020 BR00265 325 BOWERY INC. 1270 BOSTON AVE LONGMONT CO 80501 917-846-6569 BR00287 AKOS WHITE LLC 1301 ARAPAHOE ST GOLDEN CO 80401 443-257-7778 BR00238 ALASKAN BREWING CO. 5429 SHAUNE DR JUNEAU AK 99801 907-780-5866 BR00067 AMSTEL BROUWERIJ B.V. TWEEDE WETERINGPLANTSOEN 21 1017 ZDAMSTERDAM NL BR00267 ANDERSON VALLEY BREWING COMPANY 17700 HWY 253 BOONVILLE CA 95415 707-895-2337 BR00156 ASAHI BEER U.S.A. 3625 DEL AMO BLVD #250 TORRANCE CA 90503 310-214-9051 BR00291 AVERY BREWING COMPANY, LLC 4910 NAUTILUS CT N BOULDER CO 80301 303-440-4324 BR00263 BALEARIC BEVERAGE 8394 E & F TERMINAL RD LORTON VA 22079 703-550-3993 BR00199 BASE CAMP BREWING CO. -

2018 Holiday Menus

2018 HOLIDAY MENUS Proof of the Pudding has been Atlanta’s largest award-winning caterer for more than 39 years. We dish out ‘innovative culinary creations’ that are locally sourced from our purveyors to ensure the freshest, seasonally inspired ingredients. We do our best to create the vision of our clients through careful planning and collaboration. Our passionate team creates customized, creative menus for you and your guests to make your event more than memorable! testimonials “Your sales and operations team did a fabulous job for our visiting team and the all-day and night Leadership Sponsored events on that date. The Proof of the Pudding team was there with spot on, top notch service from early in the morning setting a beautiful breakfast buffet, quick change over to a perfect lunch and into the evening reception showcase event with great VEN service and great food. I was proud to have recommended Proof of the Pudding to handle the day, and our out of town team were well pleased. PRO Please pass along my gratitude to the team that took care of us on this day and I look forward to working with you on future events. Voted ‘BEST CULINARY INNOVATION ‘,’ BEST MENU Booz | Allen | Hamilton DESIGN’, ‘BEST OFF-PREMISE CATERING’, ‘ BEST ON-PREMISE CATERING’, – 2017 Allie Awards “You should know we’ve received a number of comments from attendees Proud Member of ‘Leading Caterers of America’ all positive -- regarding the quality of the dinner and overall experience. 2013 – 2017 One attendee made a specific point to tell us “The beef was the best I have had so far in my entire life!” Georgia State University Top 25 Caterers List in U.S. -

Salads Platters Eggs Wraps

SALADS *Add Chicken 4.00 | Shrimp 8.00 | Steak 8.00 House Salad* 9.00 Greek Salad* 10.00 Fresh romaine lettuce, tomatoes, onions, red & green Fresh romaine lettuce, tomatoes, onions, red & green peppers, black olives, cucumbers, avocado, shredded peppers, black olives, cucumbers, feta cheese, anchovies, carrots & cheddar cheese. avocado & grape leaves. Caesar Salad* 9.00 Salmon Nicoise Salad 18.00 Fresh romaine lettuce, cherry tomatoes, parmesan cheese, Grilled salmon fillet over romaine lettuce, tomatoes, onions, croutons & caesar dressing. red & green peppers, black olives, cucumbers, avocado, hard boiled eggs, steamed green beans, chopped baby Cobb Salad* 9.00 potatos, cappers, balsamic & olive oil. Fresh romaine lettuce, tomatoes, onions, red & green peppers, black olives, cucumbers, sweet corn, blue Taco Salad 12.00 cheese crumbles & avocado. Fried tortilla bowl with shredded lettuce, onions, red & green peppers, tomatoes, olives, cheddar cheese & avocado. Popeye’s Salad * 10.00 Choice of grilled chicken, ground beef or beans & sweet corn. Baby spinach, sundried tomatoes & avocado dressing. Taco Salad with Steak 17.00 Steak Salad 18.00 Sautéed skirt steak with soy sauce & balsamic Taco Salad with Shrimp 17.00 vingear over arugula with lime juice & olive oil. PLATTERS Served with Mexican rice & black beans. Pollo 5 de Mayo 12.00 Flautas 13.00 Sautéed chicken breast in a reduction of white wine, Rolled fried tortilla with shredded chicken. Topped with green fresh tomato, garlic, capers, & lemon juice. tomatillo sauce, lettuce, queso fresco, avocado & sour cream. Chimichangas de Carne o Pollo 12.00 Chiles Rellenos 13.00 (2) Stuffed fried flour tortilla with chicken or ground beef. -

180307 Dos Mares Diptico Carta Cenas Tres Mares 04

COCINA SALMOREJO CORDOBÉS 5.00 € GAMBAS CON SALSA DE CURRY 9.00 € SALTEADO DE LANGOSTINOS, CEBOLLA, CURRY Y LECHE DE COCO, ENSALADA DE ESPINACAS 7.00 € LIGERAMENTE PICANTE ESPINACAS FRESCAS CON FRUTOS SECOS Y CREMA FRESCA CON MIEL HAMBURGUESA CON PAN DE PITA 11.00 € HAMBURGUESA DE TERNERA ESPECIADA ENSALADA CON FETA 9.50 € ENSALADA CON QUESO FETA, OLIVAS NEGRAS, PEPINOS POLLO AL TANDORI 12.00 € Y SALSA DE YOGUR BROCHETA DE POLLO MACERADO EN PIMENTÓN HINDÚ TABOULÉ 7.00 € TAGINE DE POLLO 13.50 € ENSALADA DE SÉMOLA DE TRIGO, VEGETALES FRESCOS, GUISO DE POLLO AL ESTILO ÁRABE CON ACEITUNAS PASAS, PIÑONES Y HOJAS DE MENTA Y LIMONES CONFITADOS PIRIÑACA DE GARBANZOS TAGINE DE CORDERO 15.00 € CON TORTITAS DE PATATAS 7,00 € GUISO DE CORDERO ESPECIADO CON CIRUELAS ENSALADA DE GARBANZOS, PIMIENTOS, PEPINO Y OLIVAS ACOMPAÑADO CON TORTITAS DE PATATAS TAGINE DE RAPE 17.00 € GUISO DE RAPE CON LANGOSTINOS Y PISTACHOS SAMOSAS DE PATATAS 6.00 € TRIANGULITOS FRITOS RELLENOS DE PATATA, GUISANTE MADRÁS DE TERNERA (PICANTE) 17.00 € Y COL ESPECIADA CURRY ROJO DE TERNERA BÖREKS 7.00 € CRUJIENTE DE ATÚN A LAS 5 ESPECIAS 17.00 € PASTELITOS CRUJIENTES RELLENOS DE QUESO FETA, LOMO DE ATÚN ENVUELTO EN 5 ESPECIAS Y PASTA FILO MOZZARELLA Y FRUTOS SECOS CON CULIS DE MELOCOTÓN Wi Fi FALAFEL 6.00 € 10% IVA INCLUIDO ALBÓNDIGAS DE GARBANZOS, CEBOLLA Y PEREJIL ZONE CON SALSA DE YOGUR Y MENTA “En cumplimiento de la normativa sanitaia vigente, este establecimiento garantiza que los produc- tos de la pesca de consumo en crudo o los que por su proceso de elaboración no han recibido un calentamiento superior a 60º C en el centro de producción, se han congelado a -20º durante al menos 24 horas” El Real Decreto 1420/2006 del 1 de diciembre, sobre prevención de la parasitosis DEGUSTACIÓN ÁRABE 12.00 € por anisakis en productos de la pesca suministrados por establecimientos que sirven comida a los TABOULÉ, PIRIÑACA, SAMOSAS, BÖREKS Y FALAFEL consumidores finales o colectividades. -

El Menu Apps Substantials Guacamole 14 Carne Asada 28 with Crispy Tortilla Chips

El Menu Apps Substantials Guacamole 14 Carne Asada 28 with crispy tortilla chips. can be spicy upon request VGF Grilled flank steak, roasted onion, black beans & Mexican style rice Cali Cauli 9 Fajitas chicken 24 steak 26 crispy fish 28 veggie 25 crispy roasted cauliflower with a warm verde sauce VGF served with warm flour tortillas, lettuce, pico de gallo & guacamole Chicken Quesadilla 14 GF 19 grilled flour tortillas filled with cheese, chicken, onions and peppers Chicken Enchiladas with Verde Sauce Veggie Quesadilla 14 Vegan Enchiladas with Roja Sauce VGF 18 grilled flour tortillas with cheese, seasonal vegetables, onions and peppers servied with freshly pressed corn tortillas Queso Fundido GF 12 zingy, creamy, cheesy goodness. Served with crispy tortilla chips Tortas & Burgers Buffalo Chicken Wings GF 15 Baja Chicken Torta 11 mild, hot or dry-rubbed traditional Mexican sandwich of crispy chicken, homemade chipotle mayo, cabbage slaw, black beans, queso fresco Avocado Fries V 10 avocados elevated & paired with chipotle aioli Pepito Short Ribs Torta 13 braised short ribs, caramelized onion, artisan Jack cheese, black beans, Tijuana Fries V 9 pickled jalapeños French fries topped with queso, jalapenos, pico de gallo & sour cream. Salsa Trio VGF 8 Piquante Heritage Pork Torta 12 crispy chips served with 3 salsas seasoned rotisserie pork loin, bacon, black beans & sliced avocado Nachos with Chicken GF 14 Blues Burger 14 tex-mex classic corn chips topped with cheese, beans, peppers hand-formed burger topped with cheddar cheese and caramelized -

Burguer Kebab Málaga 1

Para Compartir Ensaladas Burguer Kebab Málaga 1. PATATAS FRITAS...........2,50 1. COMPLETA.............5,50 2. PATATAS CON QUESO . 4,00 lechuga, tomate, queso, jamón, maíz, desde 1998 yogur, bacon y queso atún y aceitunas C/ Gerona, 45 desde 1998 3. PATATAS KEBAB...........5,50 2. TROPICAL..............5,50 ) queso, shawarma y salsas de la casa 605 11 94 44 (RESERVAS Y PEDIDOS PARA RECOGER) lechuga, maíz, piña, bocas de mar, 4. PATATAS GAJO ............3,20 5. PATATAS REJILLA . 3,50 langostinos y salsa rosa 6. PALITOS DE QUESO 3. KEBAB .................6,00 l 00 % 3 ud. 2,20 / 6 ud. 4,00 / 12 ud. 7,00 lechuga, tomate, cebolla y shawarma EL PO AB L ORAC LO IO N CA Shaw arma Caser o SE 7. ALITAS MARINADAS 4. CÉSAR .................6,20 RA 6 ud. 3,50 / 12 ud. 6,00 lechuga, queso en dados, picatostes, patata 8. BOCADITOS CHEDDAR PICANTE pollo crujiente y salsa césar pita rollo campero asada 6 ud. 3,20 / 12 ud. 6,00 5. SUPREMA ..............6,60 9. AROS DE CEBOLLA lechuga gourmet, bacon, nueces, a 1. COMPLETO . 4,00 . 4,50 . 4,70. 4,00 6 ud. 2,80 / 12 ud. 5,00 queso dados, picatostes, pollo g lechuga, tomate, cebolla, pepinillo, yogur, picante y alioli a crujiente y salsa mostaza miel l + QUESO...............4,20.4,70 ..4,90...4,20 á M ,50 Pulguitas € 2. SOLO CARNE . 4,50 . 4,80 . 5,00. 4,50 1 b salsa yogur, picante, salsa rosa y alioli Patatas A sadas a 1. ATÚN, TOMATE, CEBOLLA Y b + QUESO...............4,70.5,00 ..5,00...4,80 MAYONESA Ingrediente adicional: +0,60 e K 2. -

Lunch Through Dinner

QTY Entradas Guacamole & Totopos $8 traditional setup with warm tortilla chips Arroz con Frijoles $2.5 MEXICAN rice / epazote black beans Corn Esquites $5 mayo/ chile/ cotija CHIPS & Salsa $3 HOUSE MADE ORGANIC CHIPS / SALSAS Taquitos $6 crispy potato & cheese filled tortillas Tacos Al Pastor $3 spit roasted pork / pineapple Pollo $2.5 Achiote grilled chicken / black bean / pico Chicharron de Pescado $3.5 crispy local skate / lemon mayo / cabbage Camaron $4 CRISPY shrimp / SALSA VERDE / CABBAGE Dorado $3.5 grilled mahi mahi / cabbage Lengua $3.5 beef tongue/ bacon / poblano Barbacoa $3.5 slow roasted beef shoulder / onion Carne Asada $4 steak/ onion Champignon $3 mushroom/ poblano / GUAJILLO Carnitas $3.5 mexican coca cola pork Chorizo $3.5 langenfeller farms HOUSE sausage / QUESO Queso $2.5 crispy cheese / avocado Tostadas Atun $6 ahi tuna / guacamole / SESAME SaNGRITA MARISCADA $7 Shrimp / crab / spicy tomato / guacamole QTY Quesadillas Pollo $8 chicken / oaxaca cheese / poblano El Machete $7 organic masa / oaxaca cheese / poblano / corn Tortas Milanesa $9 fried chicken / bean puree / avocado Pepito $13 chopped ribeye / bean puree / avocado Carnitas Ahogado $11 spicy smothered pork / onion / radish Choriqueso $11 langenfeller farms house chorzo / oaxaCa cheese Cubana $12 ham / carnitas / hot dog / gruyere / CHICHARRON hamburguesa $13 roSeda farms beef / house bacon / guacamole / gruyere Dulces & SHAKES Churros $5 Cajeta / chocolate LECHE DE COCO $7 COCONUT MILK / almond BUTTER / RASPBERRY SORBET MANI $7 VANILLA ICE CREAM / PEANUT / CHOCOLATE / MARSHMALLOW LA MALTA CABRA $7 VANILLA ICE CREAM / GOATS MILK CARAMEL / MALT BANANA / WHITE CHOCOLATE AZTECA $7 CHOCOLATE ICE CREAM / PECAN BRITTLE / SMOKED AGAVE AGUA FRESCAS TAMARIND | JAMAICA PINEAPPLE MINT | HORCHATA $4. -

Menu Template.Qxd 10/27/20 2:52 PM Page 2

Angelos Pizza 10.20_Menu Template.qxd 10/27/20 2:51 PM Page 1 A e 3 M g d 2 , t a # t e S LUNCH D s t g I i t Hot Grinders o Seafood d r A i P s m r P r r b S e Dinner salad & garlic bread included Cold Upon Request P 8In. 16In. r P U u t COUPONS MEATBALL .....................................................................6.50 12.75 S FISH N CHIPS ......................................................... 12.50 AVAILABLE TUES.- FRI. FRIED CLAM STRIP .............................................12.50 11 am - 2 pm ONLY PEPPERONI ...................................................................7.25 14.00 SAUSAGE ........................................................................7.25 14.00 NEW! FRIED SCALLOPS ........15.50 FRIED SHRIMP ........15.50 EGGPLANT ......................................................................7.25 14.00 FRIED SEAFOOD PLATTER Fish, Scallops, Shrimp, Clam Strips .....16.50 L1 DOUBLE CHICKEN CUTLET PARM .......................................8.75 17.00 Above served with French Fries and Cole Slaw SHRIMP PARMESAN OVER PASTA .......................................15.95 CHEESEBURGER ABOVE come with Sauce, Provolone, Red Roasted Peppers VEGGIE BURGER .........................................................6.50 12.75 DELUXE 12 OZ (Extra Lean) Italian Dinners (Lettuce, tomato & pickle) HAM ...............................................................6.50 12.75 GENOA ...........................................................................6.50 12.75 Dinner salad & garlic bread included WITH FRIES CAPICOLA -

Appetizers Salads from the Sea from the Land Mexican Specialties

MENU Salads Appetizers Lol-Ha Guacamole Lettuce mixed with tomato, bacon, avocado, celery, Served with fresh tortilla chips, ideal for sharing. Monterrey Jack cheese and our famous house dressing. Prepared at your table. Apple Mini Empanadas Tender mixture of lettuces with apple slices, Order of four, stuffed with shrimp, chicken mole, chorizo goat cheese, cranberries and caramelized walnut. with potato and slices of poblano chili with cheese. Sprinkled with sweet and sour balsamic dressing. Accompanied by green tomatillo sauce and sour cream. Caesar Tuna Tartar Served with parmesan cheese and our homemade Marinated tuna pieces in soy sauce and ginger, avocado, Caesar dressing. Add chicken. mango, seaweed and pita bread to accompany. Delicious! Blue Cheese Seafood Cakes Iceberg lettuce wedge with a homemade Delicate seafood cakes with a chipotle dressing and mini salad. blue cheese dressing and crispy bacon. Queso Fundido Mixture of grated cheeses, served with flour and corn tortillas. From the Land Add arrachera or chorizo. Veal Osso Buco Octopus Tostadas Octopus sautéed in garlic, red onion, ginger and guajillo chile, Juicy and tender veal cut, slowly cooked in the oven, flambéed with a chile liqueur, and topped with avocado. accompanied by mashed potatoes with parmesan cheese. Fillet Mignon 8oz./240gms. From the Sea Juicy cut wrapped with bacon, cooked on the grill. Served with baked potato and vegetable of the day. Tropical Tuna Grilled Tuna loin with grilled sesame seeds, wasabi flavored Rib Eye Steak 14oz./420gms. mashed potatoes, seaweed salad and a ginger soy sauce. Delicately cut cooked on the grill, with baked potato and vegetables of the day. -

Voluptajpm & Associés Fotografía: Marielys Lorthios Groupe SEB

Concepto y realización gráfica: voluptaJPM & Associés Fotografía: Marielys Lorthios Groupe SEB Realización culinaria: Marion Guillemard ©JPM & Associés • marketing - design - communication • www.jpm-associes.com • 02/2018 1520004062-02 volupta recetario SAS SEB-21261 SELONGEY CEDEX RCS 302 412 226 Reservados todos los derechos Edición impresa en Julio de 2017 – Portugal ISBN N° 978-2-37247-035-3 www.moulinex.es Sopas y cremas ................................................. p. 4 - p. 12 Platos fáciles para el dia a dia ....... p. 12 - p. 21 Aperitivos con familia y amigos ..........p. 22 - p. 26 Guisos y estofados .............................................. p. 27 - p. 34 Platos para llevar ............................................ p. 35 - p. 37 Postres rápidos ......................................... p. 38 - p. 45 Meriendas deliciosas ......................p. 46 - p. 51 Bebidas y dulces .................................p. 52 - p. 55 Pastelitos y galletas ..................... p. 56 - p. 59 ¡Volupta tiene un libro de 100 recetas fáciles 5 ACCESORIOS QUE FACILITAN TU VIDA COTIDIANA que te permiten cocinar todos los días una comida diferente desde el aperitivo hasta el postre! No hay necesidad de cortar, mezclar o batir, ¡Volupta se encarga de todo para ti! 5 PROGRAMAS AUTOMÁTICOS PARA COCINAR LO QUE QUIERAS Cocina cremas y sopas, guisos y estofados, platos al vapor, postres y además recalienta tus platos Vapor P opa ost Cuchilla picadora Cuchilla amasadora/ Mezclador S re trituradora go lento Rec ue al f en a t a n r ó i c c o C Batidor Cestillo para vapor Las recetas son para un máximo de 4 personas. Se recomienda respetar las cantidades indicadas para un mejor resultado. Los tiempos de cocción también se pueden adaptar al gusto personal. -

NACHOS Tortilla Chips, Cheese Sauce, Beans, Lettuce

NACHOS Tortilla chips, cheese sauce, beans, lettuce, SOPES Thick fluffy tortilla topped with beans, lettuce, tomato, tomato, sour cream, cotija cheese, Your choice of chicken, sour cream & cotija cheese. Your choice of chicken, steak, chorizo, steak, chorizo, al pastor or carnitas (shredded pork) 8.95 al pastor or carnitas (shredded pork) (Ord of 3) 8.95 QUESADILLA prepared with American & mozzarella CAMARONES AL AJILLO cheese. Your choice of chicken, steak, chorizo, al pastor Shrimp in garlic sauce 10.95 or carnitas (shredded pork) 8.95 (shrimp) 9.95 CHORIZO A LA PLANCHA GUACAMOLE Made with fresh avocado, tomato, Chorizo with green peppers, red peppers and onions 9.95 onion and cilantro ( spicy optional ) M/P DEDOS DE POLLO EN SALSA BUFFALO EMPANADAS DE POLLO O CARNE Buffalo chicken tenders 7.95 Empanadas ( chicken or beef ) (Ord of 3) 8.95 4 Rolled fried tacos TOSTADAS Flat crunchy tortilla topped with beans, FLAUTAS DE POLLO O RES lettuce, tomato, sour cream, cotija cheese. your choice of topped with lettuce, tomato, sour cream & cotija cheese. your choice of chicken or beef 8.95 chicken, steak, carnitas or chorizo (Ord of 3) 8.95 ENCHILADAS VERDES, ROJAS O MOLE In green, red BISTEC ENCEBOLLADO Thin cut sirloin steak or mole sauce. Your choice of chicken, steak, carnitas or chorizo. with sautéed onions (jalapeno optional) 17.95 topped with lettuce, tomato, sour cream & cotija cheese 16.95 BISTEC O POLLO EN SALSA VERDE CON NOPALES FAJITAS Made with green & red peppers, onions and Thin cut sirloin steak or chicken breast with cactus in green sauce 17.95 mozzarella cheese on top.