Autism As a Natural Human Variation: Reflections on the Claims of the Neurodiversity Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working with Students on the Autism Spectrum

Supporting students on the autism spectrum student mentor guidelines By Catriona Mowat, Anna Cooper and Lee Gilson Supporting students on the autism spectrum All rights reserved. No part of this book can be reproduced, stored in a retrievable system or transmitted, in any form or by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other wise without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published by The National Autistic Society 2011 Printed by RAP Spiderweb © The National Autistic Society 2011 Chapters Introduction 3 1. Understanding the autism spectrum 4-9 2. Your role as a student mentor 10-15 3. Getting started 16-23 4. Supporting a student with Asperger syndrome to… 24-29 5. Useful resources 30-33 6. Further reading 34 7. Glossary of terms 35 1 2 Introduction These guidelines were initially prepared as a resource for newly appointed student mentors supporting students with autism and Asperger syndrome at the University of Strathclyde. This guide has been rewritten as a useful resource for any university employing and training its own student mentors, or considering doing so. Readers may reproduce the guidelines, or relevant sections of the guidelines, as long as they acknowledge the source. This new version was made possible by a grant from the Scottish Funding Council in 2009, which has supported not only this publication, but also a research project (led by Charlene Tait of the National Centre for Autism Studies, University of Strathclyde) into transition and retention for students on the autism spectrum, and the delivery of a series of workshops on this topic (jointly delivered by the University of Strathclyde and The National Autistic Society Scotland). -

The Life and Times Of'asperger's Syndrome': a Bakhtinian Analysis Of

The life and times of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’: A Bakhtinian analysis of discourses and identities in sociocultural context Kim Davies Bachelor of Education (Honours 1st Class) (UQ) Graduate Diploma of Teaching (Primary) (QUT) Bachelor of Social Work (UQ) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 The School of Education 1 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the sociocultural history of ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ in a Global North context. I use Bakhtin’s theories (1919-21; 1922-24/1977-78; 1929a; 1929b; 1935; 1936-38; 1961; 1968; 1970; 1973), specifically of language and subjectivity, to analyse several different but interconnected cultural artefacts that relate to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and exemplify its discursive construction at significant points in its history, dealt with chronologically. These sociocultural artefacts are various but include the transcript of a diagnostic interview which resulted in the diagnosis of a young boy with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’; discussion board posts to an Asperger’s Syndrome community website; the carnivalistic treatment of ‘neurotypicality’ at the parodic website The Institute for the Study of the Neurologically Typical as well as media statements from the American Psychiatric Association in 2013 announcing the removal of Asperger’s Syndrome from the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5 (APA, 2013). One advantage of a Bakhtinian framework is that it ties the personal and the sociocultural together, as inextricable and necessarily co-constitutive. In this way, the various cultural artefacts are examined to shed light on ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ at both personal and sociocultural levels, simultaneously. -

Autism: Resource List

Autism: Resource List Books for Children: Ages 4 to 8 Andy and His Yellow Frisbee; by Mary Thompson; Woodbine House, 1996 Asperger's huh? A Child's Perspective; by Rosina Schnurr; Anisor, 1999 Autism; Sudipta Bardhan-Quallen; KidHaven Press, 2005 Ian's Walk: A Story About Autism; by Laurie Lears; illustrated by Karen Ritz; Albert Whitman, 1998 When My Autism Gets Too Big: A Relaxation Book for Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders; by Kari Dunn Baron; Autism Asperger Publ Co, 2004 Ages 9 to 12 Autism; Elaine Landau; Franklin Watts, 2001 Autism; by Carol Baldwin; Heinemann Library, 2002 Autism; Sarah Lennard-Brown; Raintree, 2004 Different Like Me: My Book Of Autism Heroes; Jennifer Elder; illustrations by Marc Thomas and Jennifer Elder; Jessica Kingsley, 2005 Mori's Story: A Book About a Boy With Autism; by Zachary M. Gartenberg; Lerner Publications Co., 1998 (for siblings) To Be Me; by Rebecca Elinger: WPS Creative Therapy Store, 2005 Teen Coping With Asperger Syndrome; Maxine Rosaler; The Rosen Pub. Group, 2004 Everything You Need to Know When a Brother or Sister Is Autistic; Marsha S. Rosenberg; Rosen Pub. Group, 1999 Your Life is Not a Label: A Guide to Living Fully with Autism and Asperger's Syndrome; by Jerry Newport; Future Horizons, 2001 Books for Adults: Activity Schedules for Children with Autism: Teaching Independent Behavior; by Lynn McClannahan; Woodbine House, 2003 The Asperger Parent: How to Raise a Child with Asperger Syndrome and Maintain Your Sense of Humor; by Jeffrey Cohen; Autism Asperger Publ. Co, -

Gesnerus 2020-2.Indb

Gesnerus 77/2 (2020) 279–311, DOI: 10.24894/Gesn-de.2020.77012 Vom «autistischen Psychopathen» zum Autismusspektrum. Verhaltensdiagnostik und Persönlichkeitsbehauptung in der Geschichte des Autismus Rüdiger Graf Abstract Der Aufsatz untersucht das Verhältnis von Persönlichkeit und Verhalten in der Defi nition und Diagnostik des Autismus von Kanner und Asperger in den 1940er Jahren bis in die neueren Ausgaben des DSM und ICD. Dazu unter- scheidet er drei verschiedene epistemische Zugänge zum Autismus: ein exter- nes Wissen der dritten Person, das über Verhaltensbeobachtungen, Testver- fahren und Elterninterviews gewonnen wird; ein stärker praktisches Wissen der zweiten Person, das in der andauernden, alltäglichen Interaktion bei El- tern und Betreuer*innen entsteht, und schließlich das introspektive Wissen der ersten Person, d.h. der Autist*innen selbst. Dabei resultiert die Kerndif- ferenz in der Behandlung des Autismus daraus, ob man meint, die Persönlich- keit eines Menschen allein über die Beobachtung von Verhaltensweisen er- schließen zu können oder ob es sich um eine vorgängige Struktur handelt, die introspektiv zugänglich ist, Verhalten prägt und ihm Sinn verleihen kann. Die Entscheidung hierüber führt zu grundlegend anderen Positionierungen zu verhaltenstherapeutischen Ansätzen, wie insbesondere zu Ole Ivar Lovaas’ Applied Behavior Analysis. Autismus; Psychiatriegeschichte; Wissensgeschichte; Verhaltenstherapie; Neurodiversität PD Dr. Rüdiger Graf, Leibniz-Zentrum für Zeithistorische Forschung Potsdam, Am Neuen Markt 1, 14467 Potsdam, [email protected]. Gesnerus 77 (2020) 279 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 01:45:02AM via free access «Autistic Psychopaths» and the Autism Spectrum. Diagnosing Behavior and Claiming Personhood in the History of Autism The article examines how understandings of personality and behavior have interacted in the defi nition and diagnostics of autism from Kanner and As- perger in the 1940s to the latest editions of DSM and ICD. -

Overview of Biomedical Treatments Presentation

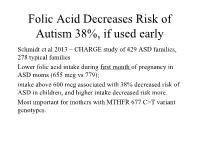

Folic Acid Decreases Risk of Autism 38%, if used early Schmidt et al 2013 – CHARGE study of 429 ASD families, 278 typical families Lower folic acid intake during first month of pregnancy in ASD moms (655 mcg vs 779); intake above 600 mcg associated with 38% decreased risk of ASD in children, and higher intake decreased risk more. Most important for mothers with MTHFR 677 C>T variant genotypes. Folic Acid decreases risk of ASD if taken near conception (cont.) Suren et al 2013 – study of 85,176 Norwegian children, including 270 with ASD. In children whose mothers took folic acid (400 mcg) between 4 weeks prior to conception to 8 weeks after conception, 0.10% (64/61 042) had autistic disorder, compared with 0.21% (50/24 134) in those unexposed to folic acid. 39% lower risk of ASD in those who took prenatal folic acid (400 mcg); Little benefit if taken after 8 weeks Overview of Dietary, Nutritional, and Medical Treatments for Autism James B. Adams, Ph.D. President’s Professor, Arizona State University President, Autism Society of Greater Phoenix President, Autism Nutrition Research Center Chair of Scientific Advisory Board, Neurological Health Foundation Father of a daughter with autism http://autism.asu.edu Our research group is dedicated to finding the causes of autism, how to prevent autism, and how to best help people with autism. Nutrition: vitamins, minerals, fatty acids, amino acids Metabolism: glutathione, methylation, sulfation, oxidative stress Mitochondria – ATP, muscle strength, carnitine Toxic Metals and Chelation Gastrointestinal -

The Relationship Between Social Skills and Challenging Behaviors in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 The elr ationship between social skills and challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders Jonathan Wilkins Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Wilkins, Jonathan, "The er lationship between social skills and challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorders" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 766. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/766 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SOCIAL SKILLS AND CHALLENGING BEHAVIORS IN CHILDREN WITH AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in The Department of Psychology by Jonathan Wilkins M.A., Louisiana State University 2008 B.A., Carleton College 1998 August 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................... -

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play As an Intervention to Support

Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis by Gregory V. Boerio Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Education in the Educational Leadership Program Youngstown State University May, 2021 Measuring the Effectiveness of Play as an Intervention to Support Language Development in Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Hierarchically- Modeled Meta-Analysis Gregory V. Boerio I hereby release this dissertation to the public. I understand that this dissertation will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: _______________________________________________________________ Gregory V. Boerio, Student Date Approvals: _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Karen H. Larwin, Dissertation Chair Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Patrick T. Spearman, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Carrie R. Jackson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew J. Erickson, Committee Member Date _______________________________________________________________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ii © G. Boerio 2021 iii Abstract The purpose of the current investigation is to analyze extant research examining the impact of play therapy on the development of language skills in young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). As rates of ASD diagnoses continue to increase, families and educators are faced with making critical decisions regarding the selection and implementation of evidence-based practices or therapies, including play-based interventions, to support the developing child as early as 18 months of age. -

Autism Entangled – Controversies Over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture

Autism Entangled – Controversies over Disability, Sexuality, and Gender in Contemporary Culture Toby Atkinson BA, MA This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sociology Department, Lancaster University February 2021 1 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Furthermore, I declare that the word count of this thesis, 76940 words, does not exceed the permitted maximum. Toby Atkinson February 2021 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank my supervisors Hannah Morgan, Vicky Singleton, and Adrian Mackenzie for the invaluable support they offered throughout the writing of this thesis. I am grateful as well to Celia Roberts and Debra Ferreday for reading earlier drafts of material featured in several chapters. The research was made possible by financial support from Lancaster University and the Economic and Social Research Council. I also want to thank the countless friends, colleagues, and family members who have supported me during the research process over the last four years. 3 Contents DECLARATION ......................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................. 3 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................. 9 PART ONE: ........................................................................................ -

Sensory Integration Used with Children with Asperger's Syndrome

Sensory Integration Used with Children with Asperger’s Syndrome Analisa L. Smith, Ed.D. Abstract Sensory Integration Program on Children with Asperger’s Syndrome This literature review will document the effects of a parent implemented Sensory Integration Program upon children diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome in order to discern its influence upon these children’s overall ability to attend to learning and social development. The infrequency of research on Asperger’s Syndrome and sensory-based programs indicates a need for further study into the potential relationship between evaluation regarding Asperger’s Syndrome and sensory- based approaches. The following literature review reflects the findings of current research within the fields of psychology, education, neurology, medicine, and occupational therapy as they pertain to Asperger’s Syndrome. Asperger’s Syndrome Volkmar and Klin (2000) state that Asperger’s Syndrome (AS) is a neuro- developmental disability that can be distinguished by limited interests and social deficits. Viennese pediatrician Hans Asperger (1943) identified the features of AS in the early 1940s and Wing (1981) gave further details about the disability's features decades later. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR, 2004), Asperger’s is classified as a Pervasive Developmental Disorder (PDD). Although, Asperger’s differs from other PDDs in that children diagnosed with AS meet normal developmental milestones in the area of language acquisition and cognitive ability. There is a continued need to research Asperger’s Syndrome (Bashe, Kirby, & Attwood, 2001). Although an AS diagnosis does not look at sensory processing deficits (DSM-IV-TR, 2004), numerous studies note that sensory deficits are common in people with AS (Barnhill, 2001; Dunn, et. -

Becoming Autistic: How Do Late Diagnosed Autistic People

Becoming Autistic: How do Late Diagnosed Autistic People Assigned Female at Birth Understand, Discuss and Create their Gender Identity through the Discourses of Autism? Emily Violet Maddox Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of Sociology and Social Policy September 2019 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................................................................. 7 CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................................. 8 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 1.1 RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ........................................................................................................................................ 8 1.2 TERMINOLOGY ................................................................................................................................................ 14 1.3 OUTLINE OF CHAPTERS .................................................................................................................................... -

Girls on the Autism Spectrum

GIRLS ON THE AUTISM SPECTRUM Girls are typically diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders at a later age than boys and may be less likely to be diagnosed at an early age. They may present as shy or dependent on others rather than disruptive like boys. They are less likely to behave aggressively and tend to be passive or withdrawn. Girls can appear to be socially competent as they copy other girls’ behaviours and are often taken under the wing of other nurturing friends. The need to fit in is more important to girls than boys, so they will find ways to disguise their difficulties. Like boys, girls can have obsessive special interests, but they are more likely to be typical female topics such as horses, pop stars or TV programmes/celebrities, and the depth and intensity of them will be less noticeable as unusual at first. Girls are more likely to respond to non-verbal communication such as gestures, pointing or gaze-following as they tend to be more focused and less prone to distraction than boys. Anxiety and depression are often worse in girls than boys especially as their difference becomes more noticeable as they approach adolescence. This is when they may struggle with social chat and appropriate small-talk, or the complex world of young girls’ friendships and being part of the in-crowd. There are books available that help support the learning of social skills aimed at both girls and boys such as The Asperkid’s Secret Book of Social Rules, by Jennifer Cook O’Toole and Asperger’s Rules: How to make sense of school and friends, by Blythe Grossberg. -

Autism & Faith Resources

AUTISM & FAITH RESOURCES BOOKS: Autism and Spirituality: Psyche, Self, and Spirit in People on the Autism Spectrum Olga Bogdashina The author argues persuasively that the spiritual development of those on the autism spectrum is in fact way ahead of that of their neurotypical peers. She describes differences in sensory perceptual, cognitive and linguistic development that make spiritual and religious experiences come more easily to those on the autism spectrum, and presents a coherent framework for understanding the routes of spiritual development and spiritual intelligence of giftedness within this group. Using research evidence and many real examples to illustrate her hypotheses, she suggests practical ways of supporting the spiritual needs of people on the autism spectrum and their families. Autism and Alleluias Kathleen Deyer Bolduc Almost everyone knows a family that has been affected by autism. What is the role that faith plays in helping families cope? In this series of slice-of-life vignettes, God's grace glimmers through as Joel, an intellectually challenged young adult with autism, teaches those who love him that life requires a childlike faith, humility, trust, and forgiveness. A Place Called Acceptance: Ministry With Families of Children With Disabilities Kathleen Deyer Bolduc The book describes how to welcome and minister to families of children with disabilities. The author discusses theology and disability, the grief process some parents experience, and the impact of disabilities on family systems. Including People with Disabilities in Faith Communities: A Guide for Service Providers, Families & Congregations Eric Carter This book addresses how faith communities, service providers, and families can work together to support the full participation of individuals with disabilities in the faith community of their choice.