A Cognitive Analysis of Cauchy's Conceptions of Function, Continuity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited)

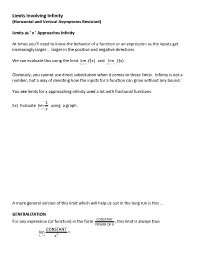

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited) Limits as ‘ x ’ Approaches Infinity At times you’ll need to know the behavior of a function or an expression as the inputs get increasingly larger … larger in the positive and negative directions. We can evaluate this using the limit limf ( x ) and limf ( x ) . x→ ∞ x→ −∞ Obviously, you cannot use direct substitution when it comes to these limits. Infinity is not a number, but a way of denoting how the inputs for a function can grow without any bound. You see limits for x approaching infinity used a lot with fractional functions. 1 Ex) Evaluate lim using a graph. x→ ∞ x A more general version of this limit which will help us out in the long run is this … GENERALIZATION For any expression (or function) in the form CONSTANT , this limit is always true POWER OF X CONSTANT lim = x→ ∞ xn HOW TO EVALUATE A LIMIT AT INFINITY FOR A RATIONAL FUNCTION Step 1: Take the highest power of x in the function’s denominator and divide each term of the fraction by this x power. Step 2: Apply the limit to each term in both numerator and denominator and remember: n limC / x = 0 and lim C= C where ‘C’ is a constant. x→ ∞ x→ ∞ Step 3: Carefully analyze the results to see if the answer is either a finite number or ‘ ∞ ’ or ‘ − ∞ ’ 6x − 3 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 5+ 2 x 3− 2x − 5 x 2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 2x + 7 5x+ 2 x −2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . -

Section 8.8: Improper Integrals

Section 8.8: Improper Integrals One of the main applications of integrals is to compute the areas under curves, as you know. A geometric question. But there are some geometric questions which we do not yet know how to do by calculus, even though they appear to have the same form. Consider the curve y = 1=x2. We can ask, what is the area of the region under the curve and right of the line x = 1? We have no reason to believe this area is finite, but let's ask. Now no integral will compute this{we have to integrate over a bounded interval. Nonetheless, we don't want to throw up our hands. So note that b 2 b Z (1=x )dx = ( 1=x) 1 = 1 1=b: 1 − j − In other words, as b gets larger and larger, the area under the curve and above [1; b] gets larger and larger; but note that it gets closer and closer to 1. Thus, our intuition tells us that the area of the region we're interested in is exactly 1. More formally: lim 1 1=b = 1: b − !1 We can rewrite that as b 2 lim Z (1=x )dx: b !1 1 Indeed, in general, if we want to compute the area under y = f(x) and right of the line x = a, we are computing b lim Z f(x)dx: b !1 a ASK: Does this limit always exist? Give some situations where it does not exist. They'll give something that blows up. -

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus We have· developed some of the basic theorems in calculus without reference to limits. However limits are very important in mathematics and cannot be ignored. They are crucial for topics such as infmite series, improper integrals, and multi variable calculus. In this last section we shall prove that our approach to calculus is equivalent to the usual approach via limits. (The going will be easier if you review the basic properties of limits from your standard calculus text, but we shall neither prove nor use the limit theorems.) Limits and Continuity Let {be a function defined on some open interval containing xo, except possibly at Xo itself, and let 1 be a real number. There are two defmitions of the· state ment lim{(x) = 1 x-+xo Condition 1 1. Given any number CI < l, there is an interval (al> b l ) containing Xo such that CI <{(x) ifal <x < b i and x ;6xo. 2. Given any number Cz > I, there is an interval (a2, b2) containing Xo such that Cz > [(x) ifa2 <x< b 2 and x :;Cxo. Condition 2 Given any positive number €, there is a positive number 0 such that If(x) -11 < € whenever Ix - x 0 I< 5 and x ;6 x o. Depending upon circumstances, one or the other of these conditions may be easier to use. The following theorem shows that they are interchangeable, so either one can be used as the defmition oflim {(x) = l. X--->Xo 180 LIMITS AND CONTINUITY 181 Theorem 1 For any given f. -

Math 137 Calculus 1 for Honours Mathematics Course Notes

Math 137 Calculus 1 for Honours Mathematics Course Notes Barbara A. Forrest and Brian E. Forrest Version 1.61 Copyright c Barbara A. Forrest and Brian E. Forrest. All rights reserved. August 1, 2021 All rights, including copyright and images in the content of these course notes, are owned by the course authors Barbara Forrest and Brian Forrest. By accessing these course notes, you agree that you may only use the content for your own personal, non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, transmit, adapt, or change in any way the content of these course notes for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of the course authors. Author Contact Information: Barbara Forrest ([email protected]) Brian Forrest ([email protected]) i QUICK REFERENCE PAGE 1 Right Angle Trigonometry opposite ad jacent opposite sin θ = hypotenuse cos θ = hypotenuse tan θ = ad jacent 1 1 1 csc θ = sin θ sec θ = cos θ cot θ = tan θ Radians Definition of Sine and Cosine The angle θ in For any θ, cos θ and sin θ are radians equals the defined to be the x− and y− length of the directed coordinates of the point P on the arc BP, taken positive unit circle such that the radius counter-clockwise and OP makes an angle of θ radians negative clockwise. with the positive x− axis. Thus Thus, π radians = 180◦ sin θ = AP, and cos θ = OA. 180 or 1 rad = π . The Unit Circle ii QUICK REFERENCE PAGE 2 Trigonometric Identities Pythagorean cos2 θ + sin2 θ = 1 Identity Range −1 ≤ cos θ ≤ 1 −1 ≤ sin θ ≤ 1 Periodicity cos(θ ± 2π) = cos θ sin(θ ± 2π) = sin -

G-Convergence and Homogenization of Some Sequences of Monotone Differential Operators

Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Östersund 2009 G-CONVERGENCE AND HOMOGENIZATION OF SOME SEQUENCES OF MONOTONE DIFFERENTIAL OPERATORS Liselott Flodén Supervisors: Associate Professor Anders Holmbom, Mid Sweden University Professor Nils Svanstedt, Göteborg University Professor Mårten Gulliksson, Mid Sweden University Department of Engineering and Sustainable Development Mid Sweden University, SE‐831 25 Östersund, Sweden ISSN 1652‐893X, Mid Sweden University Doctoral Thesis 70 ISBN 978‐91‐86073‐36‐7 i Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Mittuniversitetet framläggs till offentlig granskning för avläggande av filosofie doktorsexamen onsdagen den 3 juni 2009, klockan 10.00 i sal Q221, Mittuniversitetet, Östersund. Seminariet kommer att hållas på svenska. G-CONVERGENCE AND HOMOGENIZATION OF SOME SEQUENCES OF MONOTONE DIFFERENTIAL OPERATORS Liselott Flodén © Liselott Flodén, 2009 Department of Engineering and Sustainable Development Mid Sweden University, SE‐831 25 Östersund Sweden Telephone: +46 (0)771‐97 50 00 Printed by Kopieringen Mittuniversitetet, Sundsvall, Sweden, 2009 ii Tothememoryofmyfather G-convergence and Homogenization of some Sequences of Monotone Differential Operators Liselott Flodén Department of Engineering and Sustainable Development Mid Sweden University, SE-831 25 Östersund, Sweden Abstract This thesis mainly deals with questions concerning the convergence of some sequences of elliptic and parabolic linear and non-linear oper- ators by means of G-convergence and homogenization. In particular, we study operators with oscillations in several spatial and temporal scales. Our main tools are multiscale techniques, developed from the method of two-scale convergence and adapted to the problems stud- ied. For certain classes of parabolic equations we distinguish different cases of homogenization for different relations between the frequen- cies of oscillations in space and time by means of different sets of local problems. -

Two Fundamental Theorems About the Definite Integral

Two Fundamental Theorems about the Definite Integral These lecture notes develop the theorem Stewart calls The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in section 5.3. The approach I use is slightly different than that used by Stewart, but is based on the same fundamental ideas. 1 The definite integral Recall that the expression b f(x) dx ∫a is called the definite integral of f(x) over the interval [a,b] and stands for the area underneath the curve y = f(x) over the interval [a,b] (with the understanding that areas above the x-axis are considered positive and the areas beneath the axis are considered negative). In today's lecture I am going to prove an important connection between the definite integral and the derivative and use that connection to compute the definite integral. The result that I am eventually going to prove sits at the end of a chain of earlier definitions and intermediate results. 2 Some important facts about continuous functions The first intermediate result we are going to have to prove along the way depends on some definitions and theorems concerning continuous functions. Here are those definitions and theorems. The definition of continuity A function f(x) is continuous at a point x = a if the following hold 1. f(a) exists 2. lim f(x) exists xœa 3. lim f(x) = f(a) xœa 1 A function f(x) is continuous in an interval [a,b] if it is continuous at every point in that interval. The extreme value theorem Let f(x) be a continuous function in an interval [a,b]. -

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: an Investigation of the Henstock Integral

Generalizations of the Riemann Integral: An Investigation of the Henstock Integral Jonathan Wells May 15, 2011 Abstract The Henstock integral, a generalization of the Riemann integral that makes use of the δ-fine tagged partition, is studied. We first consider Lebesgue’s Criterion for Riemann Integrability, which states that a func- tion is Riemann integrable if and only if it is bounded and continuous almost everywhere, before investigating several theoretical shortcomings of the Riemann integral. Despite the inverse relationship between integra- tion and differentiation given by the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus, we find that not every derivative is Riemann integrable. We also find that the strong condition of uniform convergence must be applied to guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Riemann integrable functions remains in- tegrable. However, by slightly altering the way that tagged partitions are formed, we are able to construct a definition for the integral that allows for the integration of a much wider class of functions. We investigate sev- eral properties of this generalized Riemann integral. We also demonstrate that every derivative is Henstock integrable, and that the much looser requirements of the Monotone Convergence Theorem guarantee that the limit of a sequence of Henstock integrable functions is integrable. This paper is written without the use of Lebesgue measure theory. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Patrick Keef and Professor Russell Gordon for their advice and guidance through this project. I would also like to acknowledge Kathryn Barich and Kailey Bolles for their assistance in the editing process. Introduction As the workhorse of modern analysis, the integral is without question one of the most familiar pieces of the calculus sequence. -

0.999… = 1 an Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson

0 1 2 0.9999999999999999 0.999… = 1 An Infinitesimal Explanation Bryan Dawson know the proofs, but I still don’t What exactly does that mean? Just as real num- believe it.” Those words were uttered bers have decimal expansions, with one digit for each to me by a very good undergraduate integer power of 10, so do hyperreal numbers. But the mathematics major regarding hyperreals contain “infinite integers,” so there are digits This fact is possibly the most-argued- representing not just (the 237th digit past “Iabout result of arithmetic, one that can evoke great the decimal point) and (the 12,598th digit), passion. But why? but also (the Yth digit past the decimal point), According to Robert Ely [2] (see also Tall and where is a negative infinite hyperreal integer. Vinner [4]), the answer for some students lies in their We have four 0s followed by a 1 in intuition about the infinitely small: While they may the fifth decimal place, and also where understand that the difference between and 1 is represents zeros, followed by a 1 in the Yth less than any positive real number, they still perceive a decimal place. (Since we’ll see later that not all infinite nonzero but infinitely small difference—an infinitesimal hyperreal integers are equal, a more precise, but also difference—between the two. And it’s not just uglier, notation would be students; most professional mathematicians have not or formally studied infinitesimals and their larger setting, the hyperreal numbers, and as a result sometimes Confused? Perhaps a little background information wonder . -

Understanding Student Use of Differentials in Physics Integration Problems

PHYSICAL REVIEW SPECIAL TOPICS - PHYSICS EDUCATION RESEARCH 9, 020108 (2013) Understanding student use of differentials in physics integration problems Dehui Hu and N. Sanjay Rebello* Department of Physics, 116 Cardwell Hall, Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas 66506-2601, USA (Received 22 January 2013; published 26 July 2013) This study focuses on students’ use of the mathematical concept of differentials in physics problem solving. For instance, in electrostatics, students need to set up an integral to find the electric field due to a charged bar, an activity that involves the application of mathematical differentials (e.g., dr, dq). In this paper we aim to explore students’ reasoning about the differential concept in physics problems. We conducted group teaching or learning interviews with 13 engineering students enrolled in a second- semester calculus-based physics course. We amalgamated two frameworks—the resources framework and the conceptual metaphor framework—to analyze students’ reasoning about differential concept. Categorizing the mathematical resources involved in students’ mathematical thinking in physics provides us deeper insights into how students use mathematics in physics. Identifying the conceptual metaphors in students’ discourse illustrates the role of concrete experiential notions in students’ construction of mathematical reasoning. These two frameworks serve different purposes, and we illustrate how they can be pieced together to provide a better understanding of students’ mathematical thinking in physics. DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevSTPER.9.020108 PACS numbers: 01.40.Àd mathematical symbols [3]. For instance, mathematicians I. INTRODUCTION often use x; y asR variables and the integrals are often written Mathematical integration is widely used in many intro- in the form fðxÞdx, whereas in physics the variables ductory and upper-division physics courses. -

Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗

SIAM REVIEW c 2008 Walter Gautschi Vol. 50, No. 1, pp. 3–33 Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works∗ Walter Gautschi† Abstract. On the occasion of the 300th anniversary (on April 15, 2007) of Euler’s birth, an attempt is made to bring Euler’s genius to the attention of a broad segment of the educated public. The three stations of his life—Basel, St. Petersburg, andBerlin—are sketchedandthe principal works identified in more or less chronological order. To convey a flavor of his work andits impact on modernscience, a few of Euler’s memorable contributions are selected anddiscussedinmore detail. Remarks on Euler’s personality, intellect, andcraftsmanship roundout the presentation. Key words. LeonhardEuler, sketch of Euler’s life, works, andpersonality AMS subject classification. 01A50 DOI. 10.1137/070702710 Seh ich die Werke der Meister an, So sehe ich, was sie getan; Betracht ich meine Siebensachen, Seh ich, was ich h¨att sollen machen. –Goethe, Weimar 1814/1815 1. Introduction. It is a virtually impossible task to do justice, in a short span of time and space, to the great genius of Leonhard Euler. All we can do, in this lecture, is to bring across some glimpses of Euler’s incredibly voluminous and diverse work, which today fills 74 massive volumes of the Opera omnia (with two more to come). Nine additional volumes of correspondence are planned and have already appeared in part, and about seven volumes of notebooks and diaries still await editing! We begin in section 2 with a brief outline of Euler’s life, going through the three stations of his life: Basel, St. -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

Infinitesimal Calculus

Infinitesimal Calculus Δy ΔxΔy and “cannot stand” Δx • Derivative of the sum/difference of two functions (x + Δx) ± (y + Δy) = (x + y) + Δx + Δy ∴ we have a change of Δx + Δy. • Derivative of the product of two functions (x + Δx)(y + Δy) = xy + Δxy + xΔy + ΔxΔy ∴ we have a change of Δxy + xΔy. • Derivative of the product of three functions (x + Δx)(y + Δy)(z + Δz) = xyz + Δxyz + xΔyz + xyΔz + xΔyΔz + ΔxΔyz + xΔyΔz + ΔxΔyΔ ∴ we have a change of Δxyz + xΔyz + xyΔz. • Derivative of the quotient of three functions x Let u = . Then by the product rule above, yu = x yields y uΔy + yΔu = Δx. Substituting for u its value, we have xΔy Δxy − xΔy + yΔu = Δx. Finding the value of Δu , we have y y2 • Derivative of a power function (and the “chain rule”) Let y = x m . ∴ y = x ⋅ x ⋅ x ⋅...⋅ x (m times). By a generalization of the product rule, Δy = (xm−1Δx)(x m−1Δx)(x m−1Δx)...⋅ (xm −1Δx) m times. ∴ we have Δy = mx m−1Δx. • Derivative of the logarithmic function Let y = xn , n being constant. Then log y = nlog x. Differentiating y = xn , we have dy dy dy y y dy = nxn−1dx, or n = = = , since xn−1 = . Again, whatever n−1 y dx x dx dx x x x the differentials of log x and log y are, we have d(log y) = n ⋅ d(log x), or d(log y) n = . Placing these values of n equal to each other, we obtain d(log x) dy d(log y) y dy = .