Section 8.8: Improper Integrals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited)

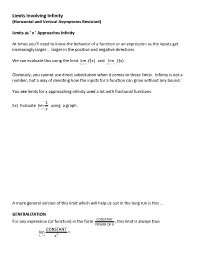

Limits Involving Infinity (Horizontal and Vertical Asymptotes Revisited) Limits as ‘ x ’ Approaches Infinity At times you’ll need to know the behavior of a function or an expression as the inputs get increasingly larger … larger in the positive and negative directions. We can evaluate this using the limit limf ( x ) and limf ( x ) . x→ ∞ x→ −∞ Obviously, you cannot use direct substitution when it comes to these limits. Infinity is not a number, but a way of denoting how the inputs for a function can grow without any bound. You see limits for x approaching infinity used a lot with fractional functions. 1 Ex) Evaluate lim using a graph. x→ ∞ x A more general version of this limit which will help us out in the long run is this … GENERALIZATION For any expression (or function) in the form CONSTANT , this limit is always true POWER OF X CONSTANT lim = x→ ∞ xn HOW TO EVALUATE A LIMIT AT INFINITY FOR A RATIONAL FUNCTION Step 1: Take the highest power of x in the function’s denominator and divide each term of the fraction by this x power. Step 2: Apply the limit to each term in both numerator and denominator and remember: n limC / x = 0 and lim C= C where ‘C’ is a constant. x→ ∞ x→ ∞ Step 3: Carefully analyze the results to see if the answer is either a finite number or ‘ ∞ ’ or ‘ − ∞ ’ 6x − 3 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 5+ 2 x 3− 2x − 5 x 2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . x→ ∞ 2x + 7 5x+ 2 x −2 Ex) Evaluate the limit lim . -

MATH 305 Complex Analysis, Spring 2016 Using Residues to Evaluate Improper Integrals Worksheet for Sections 78 and 79

MATH 305 Complex Analysis, Spring 2016 Using Residues to Evaluate Improper Integrals Worksheet for Sections 78 and 79 One of the interesting applications of Cauchy's Residue Theorem is to find exact values of real improper integrals. The idea is to integrate a complex rational function around a closed contour C that can be arbitrarily large. As the size of the contour becomes infinite, the piece in the complex plane (typically an arc of a circle) contributes 0 to the integral, while the part remaining covers the entire real axis (e.g., an improper integral from −∞ to 1). An Example Let us use residues to derive the formula p Z 1 x2 2 π 4 dx = : (1) 0 x + 1 4 Note the somewhat surprising appearance of π for the value of this integral. z2 First, let f(z) = and let C = L + C be the contour that consists of the line segment L z4 + 1 R R R on the real axis from −R to R, followed by the semi-circle CR of radius R traversed CCW (see figure below). Note that C is a positively oriented, simple, closed contour. We will assume that R > 1. Next, notice that f(z) has two singular points (simple poles) inside C. Call them z0 and z1, as shown in the figure. By Cauchy's Residue Theorem. we have I f(z) dz = 2πi Res f(z) + Res f(z) C z=z0 z=z1 On the other hand, we can parametrize the line segment LR by z = x; −R ≤ x ≤ R, so that I Z R x2 Z z2 f(z) dz = 4 dx + 4 dz; C −R x + 1 CR z + 1 since C = LR + CR. -

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma

Notes on Calculus II Integral Calculus Miguel A. Lerma November 22, 2002 Contents Introduction 5 Chapter 1. Integrals 6 1.1. Areas and Distances. The Definite Integral 6 1.2. The Evaluation Theorem 11 1.3. The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus 14 1.4. The Substitution Rule 16 1.5. Integration by Parts 21 1.6. Trigonometric Integrals and Trigonometric Substitutions 26 1.7. Partial Fractions 32 1.8. Integration using Tables and CAS 39 1.9. Numerical Integration 41 1.10. Improper Integrals 46 Chapter 2. Applications of Integration 50 2.1. More about Areas 50 2.2. Volumes 52 2.3. Arc Length, Parametric Curves 57 2.4. Average Value of a Function (Mean Value Theorem) 61 2.5. Applications to Physics and Engineering 63 2.6. Probability 69 Chapter 3. Differential Equations 74 3.1. Differential Equations and Separable Equations 74 3.2. Directional Fields and Euler’s Method 78 3.3. Exponential Growth and Decay 80 Chapter 4. Infinite Sequences and Series 83 4.1. Sequences 83 4.2. Series 88 4.3. The Integral and Comparison Tests 92 4.4. Other Convergence Tests 96 4.5. Power Series 98 4.6. Representation of Functions as Power Series 100 4.7. Taylor and MacLaurin Series 103 3 CONTENTS 4 4.8. Applications of Taylor Polynomials 109 Appendix A. Hyperbolic Functions 113 A.1. Hyperbolic Functions 113 Appendix B. Various Formulas 118 B.1. Summation Formulas 118 Appendix C. Table of Integrals 119 Introduction These notes are intended to be a summary of the main ideas in course MATH 214-2: Integral Calculus. -

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus

13 Limits and the Foundations of Calculus We have· developed some of the basic theorems in calculus without reference to limits. However limits are very important in mathematics and cannot be ignored. They are crucial for topics such as infmite series, improper integrals, and multi variable calculus. In this last section we shall prove that our approach to calculus is equivalent to the usual approach via limits. (The going will be easier if you review the basic properties of limits from your standard calculus text, but we shall neither prove nor use the limit theorems.) Limits and Continuity Let {be a function defined on some open interval containing xo, except possibly at Xo itself, and let 1 be a real number. There are two defmitions of the· state ment lim{(x) = 1 x-+xo Condition 1 1. Given any number CI < l, there is an interval (al> b l ) containing Xo such that CI <{(x) ifal <x < b i and x ;6xo. 2. Given any number Cz > I, there is an interval (a2, b2) containing Xo such that Cz > [(x) ifa2 <x< b 2 and x :;Cxo. Condition 2 Given any positive number €, there is a positive number 0 such that If(x) -11 < € whenever Ix - x 0 I< 5 and x ;6 x o. Depending upon circumstances, one or the other of these conditions may be easier to use. The following theorem shows that they are interchangeable, so either one can be used as the defmition oflim {(x) = l. X--->Xo 180 LIMITS AND CONTINUITY 181 Theorem 1 For any given f. -

Math 1B, Lecture 11: Improper Integrals I

Math 1B, lecture 11: Improper integrals I Nathan Pflueger 30 September 2011 1 Introduction An improper integral is an integral that is unbounded in one of two ways: either the domain of integration is infinite, or the function approaches infinity in the domain (or both). Conceptually, they are no different from ordinary integrals (and indeed, for many students including myself, it is not at all clear at first why they have a special name and are treated as a separate topic). Like any other integral, an improper integral computes the area underneath a curve. The difference is foundational: if integrals are defined in terms of Riemann sums which divide the domain of integration into n equal pieces, what are we to make of an integral with an infinite domain of integration? The purpose of these next two lecture will be to settle on the appropriate foundation for speaking of improper integrals. Today we consider integrals with infinite domains of integration; next time we will consider functions which approach infinity in the domain of integration. An important observation is that not all improper integrals can be considered to have meaningful values. These will be said to diverge, while the improper integrals with coherent values will be said to converge. Much of our work will consist in understanding which improper integrals converge or diverge. Indeed, in many cases for this course, we will only ask the question: \does this improper integral converge or diverge?" The reading for today is the first part of Gottlieb x29:4 (up to the top of page 907). -

Two Fundamental Theorems About the Definite Integral

Two Fundamental Theorems about the Definite Integral These lecture notes develop the theorem Stewart calls The Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in section 5.3. The approach I use is slightly different than that used by Stewart, but is based on the same fundamental ideas. 1 The definite integral Recall that the expression b f(x) dx ∫a is called the definite integral of f(x) over the interval [a,b] and stands for the area underneath the curve y = f(x) over the interval [a,b] (with the understanding that areas above the x-axis are considered positive and the areas beneath the axis are considered negative). In today's lecture I am going to prove an important connection between the definite integral and the derivative and use that connection to compute the definite integral. The result that I am eventually going to prove sits at the end of a chain of earlier definitions and intermediate results. 2 Some important facts about continuous functions The first intermediate result we are going to have to prove along the way depends on some definitions and theorems concerning continuous functions. Here are those definitions and theorems. The definition of continuity A function f(x) is continuous at a point x = a if the following hold 1. f(a) exists 2. lim f(x) exists xœa 3. lim f(x) = f(a) xœa 1 A function f(x) is continuous in an interval [a,b] if it is continuous at every point in that interval. The extreme value theorem Let f(x) be a continuous function in an interval [a,b]. -

Lecture 13 Gradient Methods for Constrained Optimization

Lecture 13 Gradient Methods for Constrained Optimization October 16, 2008 Lecture 13 Outline • Gradient Projection Algorithm • Convergence Rate Convex Optimization 1 Lecture 13 Constrained Minimization minimize f(x) subject x ∈ X • Assumption 1: • The function f is convex and continuously differentiable over Rn • The set X is closed and convex ∗ • The optimal value f = infx∈Rn f(x) is finite • Gradient projection algorithm xk+1 = PX[xk − αk∇f(xk)] starting with x0 ∈ X. Convex Optimization 2 Lecture 13 Bounded Gradients Theorem 1 Let Assumption 1 hold, and suppose that the gradients are uniformly bounded over the set X. Then, the projection gradient method generates the sequence {xk} ⊂ X such that • When the constant stepsize αk ≡ α is used, we have 2 ∗ αL lim inf f(xk) ≤ f + k→∞ 2 P • When diminishing stepsize is used with k αk = +∞, we have ∗ lim inf f(xk) = f . k→∞ Proof: We use projection properties and the line of analysis similar to that of unconstrained method. HWK 6 Convex Optimization 3 Lecture 13 Lipschitz Gradients • Lipschitz Gradient Lemma For a differentiable convex function f with Lipschitz gradients, we have for all x, y ∈ Rn, 1 k∇f(x) − ∇f(y)k2 ≤ (∇f(x) − ∇f(y))T (x − y), L where L is a Lipschitz constant. • Theorem 2 Let Assumption 1 hold, and assume that the gradients of f are Lipschitz continuous over X. Suppose that the optimal solution ∗ set X is not empty. Then, for a constant stepsize αk ≡ α with 0 2 < α < L converges to an optimal point, i.e., ∗ ∗ ∗ lim kxk − x k = 0 for some x ∈ X . -

Calculus Terminology

AP Calculus BC Calculus Terminology Absolute Convergence Asymptote Continued Sum Absolute Maximum Average Rate of Change Continuous Function Absolute Minimum Average Value of a Function Continuously Differentiable Function Absolutely Convergent Axis of Rotation Converge Acceleration Boundary Value Problem Converge Absolutely Alternating Series Bounded Function Converge Conditionally Alternating Series Remainder Bounded Sequence Convergence Tests Alternating Series Test Bounds of Integration Convergent Sequence Analytic Methods Calculus Convergent Series Annulus Cartesian Form Critical Number Antiderivative of a Function Cavalieri’s Principle Critical Point Approximation by Differentials Center of Mass Formula Critical Value Arc Length of a Curve Centroid Curly d Area below a Curve Chain Rule Curve Area between Curves Comparison Test Curve Sketching Area of an Ellipse Concave Cusp Area of a Parabolic Segment Concave Down Cylindrical Shell Method Area under a Curve Concave Up Decreasing Function Area Using Parametric Equations Conditional Convergence Definite Integral Area Using Polar Coordinates Constant Term Definite Integral Rules Degenerate Divergent Series Function Operations Del Operator e Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Deleted Neighborhood Ellipsoid GLB Derivative End Behavior Global Maximum Derivative of a Power Series Essential Discontinuity Global Minimum Derivative Rules Explicit Differentiation Golden Spiral Difference Quotient Explicit Function Graphic Methods Differentiable Exponential Decay Greatest Lower Bound Differential -

The Infinite and Contradiction: a History of Mathematical Physics By

The infinite and contradiction: A history of mathematical physics by dialectical approach Ichiro Ueki January 18, 2021 Abstract The following hypothesis is proposed: \In mathematics, the contradiction involved in the de- velopment of human knowledge is included in the form of the infinite.” To prove this hypothesis, the author tries to find what sorts of the infinite in mathematics were used to represent the con- tradictions involved in some revolutions in mathematical physics, and concludes \the contradiction involved in mathematical description of motion was represented with the infinite within recursive (computable) set level by early Newtonian mechanics; and then the contradiction to describe discon- tinuous phenomena with continuous functions and contradictions about \ether" were represented with the infinite higher than the recursive set level, namely of arithmetical set level in second or- der arithmetic (ordinary mathematics), by mechanics of continuous bodies and field theory; and subsequently the contradiction appeared in macroscopic physics applied to microscopic phenomena were represented with the further higher infinite in third or higher order arithmetic (set-theoretic mathematics), by quantum mechanics". 1 Introduction Contradictions found in set theory from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th, gave a shock called \a crisis of mathematics" to the world of mathematicians. One of the contradictions was reported by B. Russel: \Let w be the class [set]1 of all classes which are not members of themselves. Then whatever class x may be, 'x is a w' is equivalent to 'x is not an x'. Hence, giving to x the value w, 'w is a w' is equivalent to 'w is not a w'."[52] Russel described the crisis in 1959: I was led to this contradiction by Cantor's proof that there is no greatest cardinal number. -

Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative

1 Notes Chapter 4(Integration) Definition of an Antiderivative: A function F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I if for all x in I. Representation of Antiderivatives: If F is an antiderivative of f on an interval I, then G is an antiderivative of f on the interval I if and only if G is of the form G(x) = F(x) + C, for all x in I where C is a constant. Sigma Notation: The sum of n terms a1,a2,a3,…,an is written as where I is the index of summation, ai is the ith term of the sum, and the upper and lower bounds of summation are n and 1. Summation Formulas: 1. 2. 3. 4. Limits of the Lower and Upper Sums: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The limits as n of both the lower and upper sums exist and are equal to each other. That is, where are the minimum and maximum values of f on the subinterval. Definition of the Area of a Region in the Plane: Let f be continuous and nonnegative on the interval [a,b]. The area if a region bounded by the graph of f, the x-axis and the vertical lines x=a and x=b is Area = where . Definition of a Riemann Sum: Let f be defined on the closed interval [a,b], and let be a partition of [a,b] given by a =x0<x1<x2<…<xn-1<xn=b where xi is the width of the ith subinterval. -

Calculus Formulas and Theorems

Formulas and Theorems for Reference I. Tbigonometric Formulas l. sin2d+c,cis2d:1 sec2d l*cot20:<:sc:20 +.I sin(-d) : -sitt0 t,rs(-//) = t r1sl/ : -tallH 7. sin(A* B) :sitrAcosB*silBcosA 8. : siri A cos B - siu B <:os,;l 9. cos(A+ B) - cos,4cos B - siuA siriB 10. cos(A- B) : cosA cosB + silrA sirrB 11. 2 sirrd t:osd 12. <'os20- coS2(i - siu20 : 2<'os2o - I - 1 - 2sin20 I 13. tan d : <.rft0 (:ost/ I 14. <:ol0 : sirrd tattH 1 15. (:OS I/ 1 16. cscd - ri" 6i /F tl r(. cos[I ^ -el : sitt d \l 18. -01 : COSA 215 216 Formulas and Theorems II. Differentiation Formulas !(r") - trr:"-1 Q,:I' ]tra-fg'+gf' gJ'-,f g' - * (i) ,l' ,I - (tt(.r))9'(.,') ,i;.[tyt.rt) l'' d, \ (sttt rrJ .* ('oqI' .7, tJ, \ . ./ stll lr dr. l('os J { 1a,,,t,:r) - .,' o.t "11'2 1(<,ot.r') - (,.(,2.r' Q:T rl , (sc'c:.r'J: sPl'.r tall 11 ,7, d, - (<:s<t.r,; - (ls(].]'(rot;.r fr("'),t -.'' ,1 - fr(u") o,'ltrc ,l ,, 1 ' tlll ri - (l.t' .f d,^ --: I -iAl'CSllLl'l t!.r' J1 - rz 1(Arcsi' r) : oT Il12 Formulas and Theorems 2I7 III. Integration Formulas 1. ,f "or:artC 2. [\0,-trrlrl *(' .t "r 3. [,' ,t.,: r^x| (' ,I 4. In' a,,: lL , ,' .l 111Q 5. In., a.r: .rhr.r' .r r (' ,l f 6. sirr.r d.r' - ( os.r'-t C ./ 7. /.,,.r' dr : sitr.i'| (' .t 8. tl:r:hr sec,rl+ C or ln Jccrsrl+ C ,f'r^rr f 9. -

Convergence Rates for Deterministic and Stochastic Subgradient

Convergence Rates for Deterministic and Stochastic Subgradient Methods Without Lipschitz Continuity Benjamin Grimmer∗ Abstract We extend the classic convergence rate theory for subgradient methods to apply to non-Lipschitz functions. For the deterministic projected subgradient method, we present a global O(1/√T ) convergence rate for any convex function which is locally Lipschitz around its minimizers. This approach is based on Shor’s classic subgradient analysis and implies generalizations of the standard convergence rates for gradient descent on functions with Lipschitz or H¨older continuous gradients. Further, we show a O(1/√T ) convergence rate for the stochastic projected subgradient method on convex functions with at most quadratic growth, which improves to O(1/T ) under either strong convexity or a weaker quadratic lower bound condition. 1 Introduction We consider the nonsmooth, convex optimization problem given by min f(x) x∈Q for some lower semicontinuous convex function f : Rd R and closed convex feasible → ∪{∞} region Q. We assume Q lies in the domain of f and that this problem has a nonempty set of minimizers X∗ (with minimum value denoted by f ∗). Further, we assume orthogonal projection onto Q is computationally tractable (which we denote by PQ( )). arXiv:1712.04104v3 [math.OC] 26 Feb 2018 Since f may be nondifferentiable, we weaken the notion of gradients to· subgradients. The set of all subgradients at some x Q (referred to as the subdifferential) is denoted by ∈ ∂f(x)= g Rd y Rd f(y) f(x)+ gT (y x) . { ∈ | ∀ ∈ ≥ − } We consider solving this problem via a (potentially stochastic) projected subgradient method.