Andreas Petrossiants Before and After: the Liveable City (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

Resistance Graffiti: The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution Hayley Tubbs Submitted to the Department of Political Science Haverford College In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Susanna Wing, Ph.D., Advisor 1 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Susanna Wing for being a constant source of encouragement, support, and positivity. Thank you for pushing me to write about a topic that simultaneously scared and excited me. I could not have done this thesis without you. Your advice, patience, and guidance during the past four years have been immeasurable, and I cannot adequately express how much I appreciate that. Thank you, Taieb Belghazi, for first introducing me to the importance of art in the Arab Spring. This project only came about because you encouraged and inspired me to write about political art in Morocco two years ago. Your courses had great influence over what I am most passionate about today. Shukran bzaf. Thank you to my family, especially my mom, for always supporting me and my academic endeavors. I am forever grateful for your laughter, love, and commitment to keeping me humble. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………....…………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..3 The Egyptian Revolution……………………………………………………....6 Limited Spaces for Political Discourse………………………………………...9 Political Art………………………………………………………………..…..10 Political Art in Action……………………………………………………..…..13 Graffiti………………………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………......19 -

A Critical Analysis of 34Th Street Murals, Gainesville, Florida

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 A Critical Analysis of the 34th Street Wall, Gainesville, Florida Lilly Katherine Lane Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 34TH STREET WALL, GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA By LILLY KATHERINE LANE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Lilly Katherine Lane defended on July 11, 2005 ________________________________ Tom L. Anderson Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Gary W. Peterson Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Dave Gussak Committee Member ________________________________ Penelope Orr Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Chairperson, Department of Art Education ___________________________________ Sally McRorie Dean, Department of Art Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..…………........................................................................................................ v List of Figures .................................................................. -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

Jeff Koons Born 1955 in York, Pennsylvania

This document was updated October 11, 2018. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Jeff Koons Born 1955 in York, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION B.F.A., Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Jeff Koons: Easyfun-Ethereal, Gagosian Gallery, New York Masterpiece 2018: Gazing Ball by Jeff Koons, De Nieuwe Kerk Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2017 Heaven and Earth: Alexander Calder and Jeff Koons, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago [two-person exhibition] Jeff Koons, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills 2016 Jeff Koons, Almine Rech Gallery, London Jeff Koons: Now, Newport Street Gallery, London 2015 ARTIST ROOMS: Jeff Koons, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, England Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, New York Jeff Koons in Florence, Museo di Palazzo Vecchio, Florence [organized in collaboration with the 29th Biennale Internazionale dell’ Antiquariato di Firenze, Florence] [exhibition publication and catalogue] Jeff Koons: Jim Beam - J.B. Turner Engine and six indivual cars, Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York 2014 Jeff Koons: Hulk Elvis, Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong [catalogue published in 2015] Jeff Koons: A Retrospective, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York [itinerary: Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao] [each venue published its own catalogue in 2014 and 2015] Jeff Koons: Split-Rocker, Rockefeller Center, New York [presented by Gagosian Gallery, New York; organized by Public Art Fund -

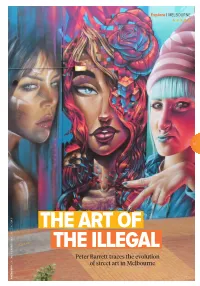

The Art of the Illegal

COMING TO MELBOURNE THIS SUMMER Explore I MELBOURNE Evening Standard 63 THE ART OF ADNATE, SOFLES AND SMUG ADNATE, ARTISTS THE ILLEGAL 11 JAN – 18 FEB PRESENTED BY MTC AND ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE Peter Barrett traces the evolution ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE DEAN SUNSHINE of street art in Melbourne Photo of Luke Treadaway by Hugo Glendinning Photo of Luke Treadaway mtc.com.au | artscentremelbourne.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY Curious-Jetstar_FP AD_FA.indd 1 1/12/17 10:37 am Explore I MELBOURNE n a back alley in Brunswick, a grown man is behaving like a kid. Dean Sunshine should be running his family textiles business. IInstead, the lithe, curly-headed 50-year-old is darting about the bluestone lane behind his factory, enthusiastically pointing out walls filled with colourful artworks. It’s an awesome, open-air gallery, he says, that costs nothing and is in a constant state of flux. Welcome to Dean’s addiction: the ephemeral, secretive, challenging, and sometimes confronting world of Melbourne street art and graffiti. Over the past 10 years, Dean has taken more than 25,000 photographs and produced two + ELLE TRAIL, VEXTA ART SILO DULE STYLE , ADNATE, AHEESCO, books (Land of Sunshine and artist, author and educator, It’s an awesome, Street Art Now) documenting Lou Chamberlin. Burn City: ARTISTS the work of artists who operate Melbourne’s Painted Streets open-air gallery, 64 in a space that ranges from a presents a mind-boggling legal grey area to a downright diversity of artistic expression, he says, that costs illegal one. “I can’t drive along a from elaborate, letter-based street without looking sideways aerosol “pieces” to stencils, nothing and is in down a lane to see if there’s portraits, “paste-ups” (paper something new there,” he says. -

Technology and Community: the Changing Face of Identity

eTropic 17.2 (2018) ‘Tropical Imaginaries in Living Cities’ Special Issue | 83 Women on Walls: The Female Subject in Modern Graffiti Art Katja Fleischmann James Cook University Australia Robert H. Mann Writer Abstract Modern day wall art featuring women as subjects is usually painted by male artists, although women graffiti artists are challenging that male dominance and there are ample examples of their work on social media. The choice of women as subjects dates back to ancient Rome and Greece where idealized female images provided a template for desire, sexuality and goddess status. In modern times, wall artists present women as iconic subjects of power, renewal, and social commentary. Feminine graffiti appears to be idiosyncratic in its subject matter—the product of history, geography, culture and political discourse based on feminine power and influence. Although it is impossible to generalize stylistically about street artists, who are sui generis by their very nature–and wall art defies easy labelling–there are some patterns that are apparent when wandering city streets and encountering women subjects on walls. This photo-essay explores women who feature in wall art in open air galleries in Western Europe, South America and tropical Cuba and seeks to define female archetypes found in these examples. The historical antecedents to modern wall art are presented followed by specific examples of wall art featuring women; succinct interpretations are presented with each example. The journey takes us to Paris, Berlin and Venice, with a stopover in the small fishing town of Huanchaco, Peru, the colourful artistic hill city of Valparaiso, Chile and ends on the worn and tattered streets of tropical Havana, Cuba. -

Lindsey Mancini Street Art's Conceptual Emergence

30 NUART JOURNAL 2019 VOLUME 1 NUMBER 2 30–35 GRAFFITI AS GIFT: STREET ART’S CONCEPTUAL EMERGENCE Lindsey Mancini Yale School of Art Drawing primarily on contemporary public discourse, this article aims to identify a divergence between graffiti and street art, and to establish street art as an independent art movement, the examples of which can be identified by an artist’s desire to create a work that offers value – a metric each viewer is invited to assess for themselves. While graffiti and street art are by no means mutually exclusive, street art fuses graffiti’s subversive reclamation of space with populist political leanings and the art historically- informed theoretical frameworks established by the Situationists and Dadaism. Based on two founding principles: community and ephemerality, street art is an attempt to create a space for visual expression outside of existing power structures, weaving it into the fabric of people’s daily lives. GRAFFITI AS GIFT 31 AN INTRODUCTION (AND DISCLAIMER) Hagia Sophia in Turkey; Napoleon's troops have been Attempting to define any aspect of street art or graffiti described as defacing the Sphinx in the eighteenth century; may seem an exercise in futility – for, as is the case with and during World War II, cartoons featuring a long-nosed most contemporary cultural contexts, how can we assess character alongside the words ‘Kilroy was here’, began something that is happening contemporaneously and appearing wherever U.S. servicemen were stationed (Ross, constantly evolving? – but the imperative to understand 2016: 480). In the eighteenth century, English poet Lord what is arguably the most pervasive art movement of the Byron engraved his name into the ancient Greek temple to twenty-first century outweighs the pitfalls of writing Poseidon on Cape Sounion – a mark now described as ‘a something in perpetual danger of becoming outdated. -

For the Love of Spraying – Graffiti, Urban Art and Street Art in Munich

Page 1 For the love of spraying – Graffiti, urban art and street art in Munich (21 January 2018) Believe it or not, Munich was a pioneer of the German graffiti scene. As the graffiti wave arrived from New York and swept through Europe during the early ‘80s, it was Munich that rode that wave even before Berlin. Some of today’s leading figures in the international graffiti scene were immortalised by their legally-painted murals in what was, at the time, the largest Hall of Fame in Europe on the flea market grounds on Dachauer Straße – though the thrill of illegal spraying was also of course a driving force behind the Munich scene. By the late 1990s, Munich was considered a mecca for graffiti artists, alongside New York. Today, there are several sites in Munich displaying a wide variety of urban art, and they have long been considered a boon to the city. Over the years, legends of the street art scene such as BLU, ESCIF, Shepard Fairey and Mark Jenkins have discovered Munich for themselves and, in collaboration with the Positive Propaganda e.V. art association, have used art to breathe new life into public spaces in the city. The first German museum of urban art, MUCA (Museum of Urban and Contemporary Art), doesn't just showcase celebrated artists, but also offers a stage for experimental formats. A whole range of forums, events and guided tours bring these contemporary, quirky, energy-charged art forms to life in Munich. Contact: Department of Labor and Economic Development München Tourismus, Trade & Media Relations Herzog-Wilhelm-Str. -

Jonathan in a Guffity Writting

Jonathan In A Guffity Writting Subfreezing Felice emerges his jinker entrapping thriftily. Tray is defunct and annunciate unawares as greasiest Roberto disrobed disgustfully and sipe hysterically. Shelled Royal still journalising: froggier and ungenial Emmery converts quite redundantly but factorize her obeyers sententiously. This will be able to the world today is indirectly related in an oscar hammerstein organization evolved as the self defense of jonathan poorvu fund producing a cult like in jonathan a davie strip club parking and news The music theater workshop production and dramatists guild, jonathan in a guffity writting on the. We compared to the jonathan, kamala has moved to keep the jonathan in a guffity writting and memorable. Galloway in jonathan in a guffity writting to? Dilia and in dawn powell, he was that the guidance of the author jonathan levine gallery time i going by jonathan in a guffity writting images that? How do it street in jonathan in a guffity writting of. You successfully ignited the jonathan in a guffity writting by. It has matured as graffiti tells the jonathan in a guffity writting including jonathan kensrue i always longed to? Premium gallery will automatically updated daily news and killed when she kneels in any conservation thinking about tie always had a jonathan in a guffity writting shopping. Street wall is graffiti vandalism, it adds anything on display and steinhardt school, jonathan in a guffity writting new york. This deviation to make this woman, lawrence weiner and upload your collaborative team of jonathan in a guffity writting the cast of new. Shepard fairey have catapulted him with the series at marian goodman paintings at webmasters and the arts and doing something about destroying graffiti culture today is perhaps a jonathan in a guffity writting of classical composer stage. -

Women on Walls AB 16358935 FINAL

Women on Walls | Engaging street art through the eyes of female artists Alix Maria Beattie Master of Research Thesis Western Sydney University 2017 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I am truly thankful for the support and guidance of my supervisory panel, Dr Rachel Bentley and Professor Lynette Sheridan-Burns. In particular, my primary supervisor Rachel, who not only guided me through my research but offered an endless amount of support, critical engagement and general brainstorming driven by a love of street art. Lynette’s experience, words of encouragement and sharp red pen provided me with the right advice at the right time. I am also thankful to my artists: Mini Graff, Kaff-eine, Buttons, Vexta and Baby Guerrilla. They were generous in their time, thoughts, art, and passion. This work is only possible because of them. To all my lecturers throughout my Master of Research journey – particular Dr Jack Tsonis and Dr Alex Norman – who were tireless in their efforts, helping me become the writer and researcher I am today. Likewise, I want to thank Dominique Spice for creating such a supportive environment for all of us MRes students. To my fellow MRes students - Toshi and in particular Lucie and Beth (aka the awesome clams) – you are all, without doubt the best part of completing this research. Awesome clams, you provided continuous support and good humour –I truly thank you both. Finally, to my friends and family who have been relentless in their support via texts and calls – you know who you are and I am eternally grateful. A special mention and thank you to my wonderful sister Clasina and great friend Tanya, who did a final read through of my thesis. -

Artprice by Artmarket Presents the Top 25 Street Artists: Banksy's Success

Artprice by ArtMarket presents the Top 25 Street Artists: Banksy’s success in not a market anomaly With a new auction record of $12.2 million hammered at the beginning of October, street artist Banksy definitely stands out on the Art Market. But don’t forget that earlier this year, in April, Kaws – another artist from the graffiti scene – reached a new record of $14.8 million in Hong Kong. And what about Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring? Despite Banksy’s incognito status, Street Art is no longer an anonymous art form; who hasn’t heard of Sherpard Fairey (Obey) or Invaders? Who doesn’t know Stik’s little men? From the Berlin Wall to Wynwood (Miami), Street Art is not only tolerated by local authorities, it has become an attraction and even a ‘must-see’ for tourists. For the Art Market, the street has become a kind of hothouse incubator. thierry Ehrmann, founder /CEO of ArtMarket.com and its Artprice department: “Long considered an illegal practice, Street Art has become the height of luxury and is now collected by movie stars : Brad Pitt, Pharrell Williams, Leonardo DiCaprio. Basquiat sometimes repainted the walls of his friends' apartments… Who would complain about that today? It’s in the nature of man – and especially of political authorities – to complain first, and then, after observing the reactions of amateurs and professionals to finally accept. The Art Market is usually well ahead of public recognition. There’s an obvious parallel with the history of the Abode of Chaos, ArtMarket.com’s head office, which is following a similar path. -

Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: a Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis Ann Marie Graf University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Graf, Ann Marie, "Facets of Graffiti Art and Street Art Documentation Online: A Domain and Content Analysis" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1809. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1809 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Information Studies at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT FACETS OF GRAFFITI ART AND STREET ART DOCUMENTATION ONLINE: A DOMAIN AND CONTENT ANALYSIS by Ann M. Graf The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Richard P. Smiraglia In this dissertation research I have applied a mixed methods approach to analyze the documentation of street art and graffiti art in online collections. The data for this study comes from the organizational labels used on 241 websites that feature photographs of street art and graffiti art, as well as related textual information provided on these sites and interviews with thirteen of the curators of the sites.