The New Realism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pussy Riot Affair: Gender and National Identity in Putin's Russia 1 Peter Rutland 2 the Pussy Riot Affair Was a Massive In

The Pussy Riot affair: gender and national identity in Putin’s Russia 1 Peter Rutland 2 The Pussy Riot affair was a massive international cause célèbre that ignited a widespread movement of support for the jailed activists around the world. The case tells us a lot about Russian society, the Russian state, and Western perceptions of Russia. It also raises interest in gender as a frame of analysis, something that has been largely overlooked in 20 years of work by mainstream political scientists analyzing Russia’s transition to democracy.3 There is general agreement that the trial of the punk rock group signaled a shift in the evolution of the authoritarian regime of President Vladimir Putin. However, there are many aspects of the affair still open to debate. Will the persecution of Pussy Riot go down in history as one of the classic trials that have punctuated Russian history, such as the arrest of dissidents Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel in 1966, or the trial of revolutionary Vera Zasulich in 1878? Or is it just a flash in the pan, an artifact of media fascination with attractive young women behaving badly? The case also poses a challenge for feminists. While some observers, including Janet Elise Johnson (below), see Pussy Riot as part of the struggle for women’s rights, others, including Valerie Sperling and Marina Yusupova, raise questions about the extent to Pussy Riot can be seen as advancing the feminist cause. Origins Pussy Riot was formed in 2011, emerging from the underground art group Voina which had been active since 2007. -

The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution

Resistance Graffiti: The Role of Political Art in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution Hayley Tubbs Submitted to the Department of Political Science Haverford College In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts Professor Susanna Wing, Ph.D., Advisor 1 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to Susanna Wing for being a constant source of encouragement, support, and positivity. Thank you for pushing me to write about a topic that simultaneously scared and excited me. I could not have done this thesis without you. Your advice, patience, and guidance during the past four years have been immeasurable, and I cannot adequately express how much I appreciate that. Thank you, Taieb Belghazi, for first introducing me to the importance of art in the Arab Spring. This project only came about because you encouraged and inspired me to write about political art in Morocco two years ago. Your courses had great influence over what I am most passionate about today. Shukran bzaf. Thank you to my family, especially my mom, for always supporting me and my academic endeavors. I am forever grateful for your laughter, love, and commitment to keeping me humble. 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements……………………………………………………....…………. 1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….……..3 The Egyptian Revolution……………………………………………………....6 Limited Spaces for Political Discourse………………………………………...9 Political Art………………………………………………………………..…..10 Political Art in Action……………………………………………………..…..13 Graffiti………………………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………......19 -

A Critical Analysis of 34Th Street Murals, Gainesville, Florida

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 A Critical Analysis of the 34th Street Wall, Gainesville, Florida Lilly Katherine Lane Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS AND DANCE A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE 34TH STREET WALL, GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA By LILLY KATHERINE LANE A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Art Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Lilly Katherine Lane defended on July 11, 2005 ________________________________ Tom L. Anderson Professor Directing Dissertation ________________________________ Gary W. Peterson Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Dave Gussak Committee Member ________________________________ Penelope Orr Committee Member Approved: ____________________________________ Marcia Rosal Chairperson, Department of Art Education ___________________________________ Sally McRorie Dean, Department of Art Education The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ..…………........................................................................................................ v List of Figures .................................................................. -

Full Study (In English)

The Long Shadow of Donbas Reintegrating Veterans and Fostering Social Cohesion in Ukraine By JULIA FRIEDRICH and THERESA LÜTKEFEND Almost 400,000 veterans who fought on the Ukrainian side in Donbas have since STUDY returned to communities all over the country. They are one of the most visible May 2021 representations of the societal changes in Ukraine following the violent conflict in the east of the country. Ukrainian society faces the challenge of making room for these former soldiers and their experiences. At the same time, the Ukrainian government should recognize veterans as an important political stakeholder group. Even though Ukraine is simultaneously struggling with internal reforms and Russian destabilization efforts, political actors in Ukraine need to step up their efforts to formulate and implement a coherent policy on veteran reintegration. The societal stakes are too high to leave the issue unaddressed. gppi.net This study was funded by the Konrad Adenauer Foundation in Ukraine. The views expressed therein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect the official position of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation. The authors would like to thank several experts and colleagues who shaped this project and supported us along the way. We are indebted to Kateryna Malofieieva for her invaluable expertise, Ukraine-language research and support during the interviews. The team from Razumkov Centre conducted the focus group interviews that added tremendous value to our work. Further, we would like to thank Tobias Schneider for his guidance and support throughout the process. This project would not exist without him. Mathieu Boulègue, Cristina Gherasimov, Andreas Heinemann-Grüder, and Katharine Quinn-Judge took the time to provide their unique insights and offered helpful suggestions on earlier drafts. -

A Militant Reconfiguration of Peter Bürger's “Neo-Avant-Garde”

Counter Cultural Production: A Militant Reconfiguration of Peter Bürger’s “Neo-Avant-Garde” Martin Lang Abstract This article re-examines Peter Bürger’s negative assessment of the neo-avant-garde as apolitical, co-opted and toothless. It argues that his conception can be overturned through an analysis of different sources – looking beyond the usual examples of individual artists to instead focus on the role of more politically committed collectives. It declares that, while the collectives analysed in this text do indeed appropriate and develop goals and tactics of the ‘historical avant-garde’ (hence meriting the appellation ‘neo-avant-garde’), they cannot be accused of being co-opted or politically uncommitted due to the ferocity of their critique of, and attack on, art and political institutions. Introduction Firstly, the reader should be aware that my understanding of the avant-garde has nothing to do with how Clement Greenberg used the term.1 I am aligning myself with Peter Bürger’s position that the ‘historical avant-garde’ was, primarily, Dada and Surrealism, but also the Russian avant-gardes after the October revolution and Futurism.2 These are movements that Greenberg saw as peripheral to the avant-garde. Greenberg did, however, share some of Bürger’s concerns about the avant-garde’s institutionalisation, or ‘academisation’ as he would put it. I borrow the term ‘neo-avant-garde’ from Bürger, but with some trepidation. In Theorie der Avantgarde (1974 – translated into English as Theory of the Avant-Garde 1984) he describes the neo-avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s as movements that revisit the historical avant- garde, but he dismisses them as inherently compromised: The neo-avant-garde institutionalizes the avant-garde as art and thus negates genuinely avant-gardiste intentions. -

Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected]

Vol 1 No 2 (Autumn 2020) Online: jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/nexj Visit our WebBlog: newexplorations.net Street Art Rising Marshall Soules—[email protected] This illustrated article discusses the various manifestations of street art—graffiti, posters, stencils, social murals—and the impact of street art on urban environments. Continuing perceptions of street art as vandalism contributing to urban decay neglects to account for street art’s full spectrum of effects. As freedom of expression protected by law, as news from under-privileged classes, as images of social uplift and consciousness-raising, and as beautification of urban milieux, street art has social benefits requiring re-assessment. Street art has become a significant global art movement. Detailed contextual history includes the photographer Brassai's interest in Parisian graffiti between the world wars; Cézanne’s use of passage; Walter Benjamin's assemblage of fragments in The Arcades Project; the practice of dérive (passage through diverse ambiances, drifting) and détournement (rerouting, hijacking) as social and political intervention advocated by Guy Debord and the Situationist International; Dada and Surrealist montage and collage; and the art of Quebec Automatists and French Nouveaux réalistes. Present street art engages dynamically with 20th C. art history. The article explores McLuhan’s ideas about the power of mosaic style to subvert the received order, opening spaces for new discourse to emerge, new patterns to be discovered. The author compares street art to advertising, and raises questions about appropriation, authenticity, and style. How does street art survive when it leaves the streets for galleries, design shops, and museums? Street art continues to challenge communication strategies of the privileged classes and elected officials, and increasingly plays a reconstructive role in modulating the emotional tenor of urban spaces. -

2.2. What Does the Balaclava Stand For? Pussy Riot: Just Some Stupid Girls Or Punk with Substance?

2.2. What does the Balaclava stand for? Pussy Riot: just some stupid girls or punk with substance? Alexandre M. da Fonseca 1 Abstract 5 punk singers walk into the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow, address the Mother of God herself, ask her to free Russia from Putin and “become a feminist”. They are stopped by the security and three members are later arrested. The rest is history… Nevertheless, Pussy Riot have proven to be more complex. This article aims to go beyond the dichotomies and the narratives played out in Western and Russian media. Given the complexity of the affair, this article aims to dissect the political thought, the ideas (or ideology), the philosophy behind their punk direct actions. Focusing on their statements, lyrics and letters and the brechtian way they see “art as a transformative tool”, our aim is to ask what does the balaclava stand for? Are they really just some stupid punk girls or is there some substance to their punk? Who are (politically) the Pussy Riot? Keywords: Pussy Riot; Punk and Direct Action; Political Thought; Critical Discourse Analysis; 3rd wave feminism Who are the Pussy Riot? Are they those who have been judged in court and sentenced to prison? Or those anonymous member who have shunned the two persecuted girl? Or maybe it’s everyone who puts a balaclava and identifies with the rebellious attitude of the Russian group? Then, are Pussy Riot an “Idea” or are they impossible to separate from the faces of Nadia and Masha? This is the first difficulty of discussing Pussy Riot – defining who their subject is. -

Gerasimov Doctrine” Why the West Fails to Beat Russia to the Punch

FRIDMAN In August 2018, service members from many nations were represented in the Ukrainian Independence Day parade. Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine has been ongoing since 2015 and seeks to contribute to Ukraine’s internal defense capabilities and training capacity. (Tennessee Army National Guard) 100 | FEATURES PRISM 8, NO. 2 On the “Gerasimov Doctrine” Why the West Fails to Beat Russia to the Punch By Ofer Fridman he first week of March 2019 was very exciting for Western experts on Russian military affairs. On March 2, the Russian Academy of Military Sciences held its annual defense conference with Chief of the General Staff, Army General Valery Gerasimov, giving the keynote address. Two days Tlater, official Ministry of Defense newspaper Krasnaya Zvesda published the main outlines of Gerasimov’s speech, igniting a new wave of discourse on Russian military affairs among Western experts.1 The New York Times’ claim that “Russian General Pitches ‘Information’ Operations as a Form of War” was aug- mented by an interpretation claiming that Gerasimov had unveiled “Russia’s ‘strategy of limited actions,’” which was “a new version of the ‘Gerasimov Doctrine’” that was to be considered the “semi-official ‘doc- trine’ of the Russian Armed Forces and its General Staff.”2 Interestingly enough, this echo chamber–style interpretation of Gerasimov’s speech emphasized only the one small part of it that discussed information/ propaganda/subversion/nonmilitary aspects of war. The main question, however, is whether this part deserves such attention—after all, this topic was discussed only in one short paragraph entitled “Struggle in Informational Environment.” Was there something in his speech that deserved greater attention? And if so, why was it missed? Did Russia Surprise the West? Or Was the West Surprised by Russia? Since 2014, Western experts on Russian military affairs have been trying to understand the Russian dis- course on the character of war in the 21st century, as it manifested itself in Ukraine and later in Syria. -

Dangerous Myths How Crisis Ukraine Explains

Dangerous Myths How the Crisis in Ukraine Explains Future Great Power Conflict Lionel Beehner A Contemporary Battlefield Assessment Liam Collins by the Modern War Institute August 18, 2020 Dangerous Myths: How the Crisis in Ukraine Explains Future Great Power Conflict Table of Contents Acknowledgments........................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter I — Russian Intervention in Ukraine: A Troubled History ............................................. 12 Chapter II — Russian Military Modernization and Strategy ........................................................... 21 Chapter III — Hybrid Warfare Revisited .............................................................................................. 26 Chapter IV — A Breakdown of Russian Hybrid Warfare ................................................................. 31 Proxy Warfare ..................................................................................................................................... 32 Information Warfare .......................................................................................................................... 38 Maritime/Littoral -

Jeff Koons Born 1955 in York, Pennsylvania

This document was updated October 11, 2018. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. Jeff Koons Born 1955 in York, Pennsylvania. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION B.F.A., Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, Maryland SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 Jeff Koons: Easyfun-Ethereal, Gagosian Gallery, New York Masterpiece 2018: Gazing Ball by Jeff Koons, De Nieuwe Kerk Amsterdam, Amsterdam 2017 Heaven and Earth: Alexander Calder and Jeff Koons, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago [two-person exhibition] Jeff Koons, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills 2016 Jeff Koons, Almine Rech Gallery, London Jeff Koons: Now, Newport Street Gallery, London 2015 ARTIST ROOMS: Jeff Koons, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, England Jeff Koons: Gazing Ball Paintings, Gagosian Gallery, New York Jeff Koons in Florence, Museo di Palazzo Vecchio, Florence [organized in collaboration with the 29th Biennale Internazionale dell’ Antiquariato di Firenze, Florence] [exhibition publication and catalogue] Jeff Koons: Jim Beam - J.B. Turner Engine and six indivual cars, Craig F. Starr Gallery, New York 2014 Jeff Koons: Hulk Elvis, Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong [catalogue published in 2015] Jeff Koons: A Retrospective, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York [itinerary: Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao] [each venue published its own catalogue in 2014 and 2015] Jeff Koons: Split-Rocker, Rockefeller Center, New York [presented by Gagosian Gallery, New York; organized by Public Art Fund -

Pussy Riot and Its Aftershocks: Politics and Performance in Putin’S Russia

Pussy Riot and Its Aftershocks: Politics and Performance in Putin’s Russia Victoria Kouznetsov Senior Thesis May 6, 2013 When the all-female anarcho-punk group Pussy Riot staged a protest performance at the Cathedral of Christ the Savior—the spiritual heart of Moscow—in February of 2012, which led to the arrests of three members, they provoked a flood of public responses that quickly spilled over the borders of the Russian Federation. The significance of their “performance” can be gauged by the strength and diversity of these responses, of support and condemnation alike, that were voiced so vocally in the months leading up to and following the trial of Yekaterina Samutsevich, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, and Maria Alyokhina (ages 30, 23, and 24, respectively). The discourse surrounding the group’s performance, amplified by the passions surrounding the imminent reelection of Vladimir Putin to a third term as president on May 7, 2012, reveals many emerging rifts in Russia’s social and political fabric. At a time when Russia faces increasingly challenging questions about its national identity, leadership, and role in the post-Soviet world, the action, arrest and subsequent trial of Pussy Riot serves as an epicenter for a diverse array of national and international quakes. The degree to which politicians, leaders of civil society, followers of the Russian Orthodox faith, and influential figures of the art scene in Russia rallied around the Pussy Riot trial speaks to the particularly fraught timing of the performance and its implications in gauging Russia’s emerging social and political trends. The disproportionately high degree of media attention given to the case by the West, however, has added both temporal and spatial dimensions to the case, evoking Cold War rhetoric both in Russia and abroad. -

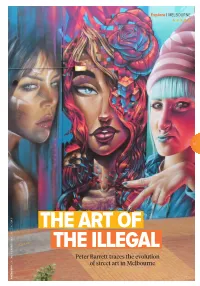

The Art of the Illegal

COMING TO MELBOURNE THIS SUMMER Explore I MELBOURNE Evening Standard 63 THE ART OF ADNATE, SOFLES AND SMUG ADNATE, ARTISTS THE ILLEGAL 11 JAN – 18 FEB PRESENTED BY MTC AND ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE Peter Barrett traces the evolution ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE, PLAYHOUSE DEAN SUNSHINE of street art in Melbourne Photo of Luke Treadaway by Hugo Glendinning Photo of Luke Treadaway mtc.com.au | artscentremelbourne.com.au PHOTOGRAPHY Curious-Jetstar_FP AD_FA.indd 1 1/12/17 10:37 am Explore I MELBOURNE n a back alley in Brunswick, a grown man is behaving like a kid. Dean Sunshine should be running his family textiles business. IInstead, the lithe, curly-headed 50-year-old is darting about the bluestone lane behind his factory, enthusiastically pointing out walls filled with colourful artworks. It’s an awesome, open-air gallery, he says, that costs nothing and is in a constant state of flux. Welcome to Dean’s addiction: the ephemeral, secretive, challenging, and sometimes confronting world of Melbourne street art and graffiti. Over the past 10 years, Dean has taken more than 25,000 photographs and produced two + ELLE TRAIL, VEXTA ART SILO DULE STYLE , ADNATE, AHEESCO, books (Land of Sunshine and artist, author and educator, It’s an awesome, Street Art Now) documenting Lou Chamberlin. Burn City: ARTISTS the work of artists who operate Melbourne’s Painted Streets open-air gallery, 64 in a space that ranges from a presents a mind-boggling legal grey area to a downright diversity of artistic expression, he says, that costs illegal one. “I can’t drive along a from elaborate, letter-based street without looking sideways aerosol “pieces” to stencils, nothing and is in down a lane to see if there’s portraits, “paste-ups” (paper something new there,” he says.