The Enoch Pratt Free Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Public Libraries Directory In

October 2021 Directory Local Touch Global Reach https://directory.sailor.lib.md.us/pdf/ Maryland Public Library Directory Table of Contents Allegany County Library System........................................................................................................................1/105 Anne Arundel County Public Library................................................................................................................5/105 Baltimore County Public Library.....................................................................................................................11/105 Calvert Library...................................................................................................................................................17/105 Caroline County Public Library.......................................................................................................................21/105 Carroll County Public Library.........................................................................................................................23/105 Cecil County Public Library.............................................................................................................................27/105 Charles County Public Library.........................................................................................................................31/105 Dorchester County Public Library...................................................................................................................35/105 Eastern -

IDEALS @ Illinois

ILLINOIS- UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Library Trends / VOLUME 14 NUMBER 4 APRIL, 1966 Current Trends in Branch Libraries ANDREW GEDDES Issue Editor CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS ISSUE ANDREW GEDDES . 365 Introduction MILTON S. BYAM . 368 History of Branch Libraries JOHN T. EASTLICK AND HENRY G. SHEAROUSE, JR. 374 Organization of a Branch System JOHN M. CARROLL . 385 Establishing Branch Libraries * WYMAN H. JONES . 401 The Role of the Branch Lidrary ih the Progrim of Metropolitai Library Service HAROLD L. HAMILL . 407 Selection, Training, and Staffing for Branch Libraries MEREDITH BLOSS . 422 The Branch Cdllectidn * LEARNED T. BULMAN . 434 Young Adult Work in Branch Libraries WALTER H. KAISER . 440 Libraries in Non-Co&olidaied Sistems' EMERSON GREENAWAY . 451 New Trends in Branch Public Liirary Sen& This Page Intentionally Left Blank Introduction ANDREW GEDDES FORALMOST one hundred years the means of ex- tending library service in metropolitan areas has been through the development of branch outlets. In general these units have been con- sidered as miniature main libraries conveniently located for easy access by all residents of the neighborhood and offering a varied range of services. Because of this structure, a substantial portion of the budget of any consolidated system is allocated to branch library operations for staff, for library materials and for building maintenance. It is also safe to assume that a great deal of administrative time as well is de- voted to the many aspects of this phase of the library program. Despite the acknowledged growth and importance of the branch library structure, it is equally clear that professional literature dealing with branch administration is almost totally lacking. -

Green V. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore's

Green v. Garrett: How the Economic Boom of Professional Sports Helped to Create, and Destroy, Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium 1953 Renovation and upper deck construction of Memorial Stadium1 Jordan Vardon J.D. Candidate, May 2011 University of Maryland School of Law Legal History Seminar: Building Baltimore 1 Kneische. Stadium Baltimore. 1953. Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore. Courtesy of Enoch Pratt Free Library, Maryland’s State Library Resource Center, Baltimore, Maryland. Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................3 II. Historical Background: A Brief History of the Location of Memorial Stadium..............................................................................................................6 A. Ednor Gardens.............................................................................................8 B. Venable Park..............................................................................................10 C. Mount Royal Reservoir..............................................................................12 III. Venable Stadium..............................................................................................16 A. Financial History of Venable Stadium.......................................................19 IV. Baseball in Baltimore.......................................................................................24 V. The Case – Not a Temporary Arrangement.....................................................26 -

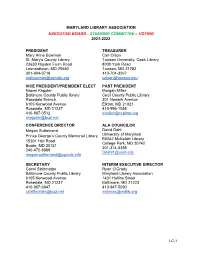

MLA Organizational Structure

MARYLAND LIBRARY ASSOCIATION EXECUTIVE BOARD - STEERING COMMITTEE – VOTING 2021-2022 PRESIDENT TREASURER Mary Anne Bowman Carl Olson St. Mary’s County Library Towson University, Cook Library 23630 Hayden Farm Road 8000 York Road Leonardtown, MD 20650 Towson, MD 21252 301-904-0718 410 - 704 - 3267 [email protected] [email protected] VICE PRESIDENT/PRESIDENT ELECT PAST PRESIDENT Naomi Keppler Morgan Miller Baltimore County Public library Cecil County Public Library Rosedale Branch 301 Newark Avenue 6105 Kenwood Avenue Elkton, MD 21921 Rosedale, MD 21237 410 - 996 - 1055 410-887-0512 [email protected] [email protected] CONFERENCE DIRECTOR ALA COUNCILOR Megan Sutherland David Dahl Prince George’s County Memorial Library University of Maryland B0242 McKeldin Library 15301 Hall Road College Park, MD 20742 Bowie, MD 20721 301-314-0395 240-472-8889 [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY INTERIM EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Conni Strittmatter Ryan O’Grady Baltimore County Public Library M ary land Library Association 6105 Kenwood Avenue 1401 Hollins Street Rosedale, MD 21237 Baltimore, MD 21223 410-887-6047 410 - 947 - 5090 [email protected] [email protected] I-C-1 EXECUTIVE BOARD – APPOINTED OFFICERS - VOTING 2021-2022 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT LEGISLATIVE Tyler Wolfe Andrea Berstler Baltimore County Public Library Carroll County Public Library 3202 Bayonne Avenue 1100 Green Valley Road Baltimore, MD 21214 New Windsor, MD 21776 410-905-6866 443-293-3136 cell: 443-487-1716 [email protected] [email protected] INTELLECTUAL FREEDOM Andrea -

History of Urban Main Library Service

History of Urban Main Library Service JACOB S. EPSTEIN THEMOST IMPORTANT early date for urban public libraries would certainly be 1854, the year the Boston Public Library opened its doors. But as Jesse Shera has noted: “The opening, on March 20,1854, of the reading room of the Boston Public Library. ..was not a signal that a new agency had suddenly been born into American urban life. Behind the act were more than two centuries of experimentation, uncertainty, and change.”l Before the advent of public libraries there were numerous social li- braries, mercantile libraries and other efforts to have a community store of books which could be borrowed or consulted. A common prin- ciple evident in each of them was the belief that the printed word was important and should be made available to the ordinary citizen who could not own all the literature which was of value. Although it was a subscription library, rather than a public library as we think of it today, Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Phila- delphia, organized in 1731, was the first library in America to circulate books and the first to pay a librarian for his services. In his Autobiogra- phy, Franklin declared, “These libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans, made the common tradesmen and farm- ers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the stand so generally made throughout the colonies in defense of their privileges.”2 Here is that recurrent theme of self-improvement that runs throughout the Ameri- can public library movement. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Baltimore East/South Clifton Park Historic District (B-5077) other names 2. Location Area approx. bounded by Clifton Park on the north, North Broadway on the street & number west, E. Chase St. on the south, and N. Rose St on the east • not for publication city or town Baltimore • vicinity state Maryland code MP county Independent City _ code 510 zip code 21213 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this S nomination • quest for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Groufi Serwices in Public Libraries GRACE T

ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. Librarv/ Trends VOLUME 17 NUMBER 1 JULY, 1968 Groufi Serwices in Public Libraries GRACE T. STEVENSON Issue Editor CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS I,SSUE GRACE T. STEVENSON , 3 Introduction RUTHWARNCKE . * 6 Library Objectives and Commur& Needs RUTH W. GREGORY ' 14 The Search for information' Aboui Comrnunik Nekds KATHERINE LORD O'BRIEN . 22 The Library and Continuing Edkation DOROTHY SINCLAIR . 36 Materials to Meet Special Needs ' MILDRED T. STIBITZ . 48 Getting the Word Ardund ' JEWELL MANSFIELD ' 58 A Public Affairs Progiam-?he &troit'Publib Libiary LILLIAN BRADSHAW * 62 Cultural Programs-~e Dailas kblic Libra& FERN LONG 68 The Live Lon :and Like It'Library ClAb-fhe Cleveland Public Li%rary EMILY W. REED , 72 Working with Local Organization's-"& Endch PrHtt Frke Lidrary ' ELLEN L. WALST-I . 77 A Program Planners Skries-The Sea& Pubiic Library ' EDITH P. BISHOP , . 81 Service to the Disadvantage>: A Pilot Projeci-Thk Los 'Angeies Public Library R. RUSSELL h."N . 86 Library Leadership through Adult Group Services-An Assessment ELEANOR PHLNNEY . 96 Trends and Neehs: The Present Condiiion ahd Fiture * Improvement of Group Services Introduction GRACE T. STEVENSON THECONCEPT OF “group services” on which the articles in this issue of Library Trends are based is not original, but was formulated out of years of observation, discussion and practice. Formulated in late 1965, it is the same as that stated by Robert E. Lee in his Continuing Education for Adults Through the American Public Library, which was published in 1966. -

Market Center Strategic Revitalization Plan Advisory Committee (In Alphabetical Order)

Market Center Strategic Revitalization Plan Advisory Committee (in alphabetical order) The following entities have been invited to participate on the Advisory Committee, but we are open to adding more Advisory Committee members. To serve on the Advisory Committee, you must be willing to commit time to meetings and reviewing documents between meetings. If you are interested in serving on the Advisory Committee, please contact Kristen Mitchell at 443-478-3014. There are also other substantive ways to participate in this planning process, including focus groups, subcommittee meetings on specific subjects, such as housing and transportation, and public meetings. 1. Baltimore Development Corporation, Kyree West 2. Baltimore Heritage, Johns Hopkins 3. Baltimore Leadership School for Young Women (Invited) 4. Behavioral Health System Baltimore, Mark Slater 5. Bromo Arts & Entertainment District 6. Catholic Relief Services, Janee Franklin 7. City Center Residents Association 8. Downtown Partnership of Baltimore 9. Enoch Pratt Free Library (Invited) 10. Greater Baltimore Urban League (Invited) 11. Lexington Market, Inc., Robert Thomas 12. Market Center Community Development Corporation, Wendy Blair 13. Market Center Merchants Association, Judson Kerr 14. University of Maryland, Baltimore, Stuart Sirota 15. University of Maryland Medical Center, Samuel Burris 16. Veterans Administration Hospital, Stephanie O’Connell Resource Team: 1. Baltimore City Department of Planning, Reni Lawal 2. Baltimore City Department of Transportation, Theo Ngongang 3. Maryland Transit Administration, Patrick McMahon 4. Maryland Stadium Authority, Rachelina Bonacci 5. Maryland Department of Planning, Victoria Olivier 6. Maryland Department of Housing & Community Development, Nick Mayr 7. Representative of Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young 8. Representative of Council President Brandon Scott, Scott Davis 9. -

Dukedomlarge00reynrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley of California Oral History Office University Regional California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, Library School Oral. History Series and Leaders Series University of California, Source of Community Flora Elizabeth Reynolds S ENOUGH": FORTY YEARS IN NORTHERN CALIFORNIA "A DUKEDOM LARGE PUBLIC AND ACADEMIC LIBRARIES, 1936-1976 With an Introduction by Charles and Grace Larsen Interviews Conducted by Laura McCreery in 1999 the of California Copyright O 2000 by The Regents of University Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Flora Elizabeth Reynolds dated June 14, 1999. -

Special Libraries, July-August 1965

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1965 Special Libraries, 1960s 7-1-1965 Special Libraries, July-August 1965 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1965 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, July-August 1965" (1965). Special Libraries, 1965. 6. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1965/6 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1960s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1965 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Putting Knowledge to Work OFFICERS DIRECTORS President WILLIAMK. BEATTY ALLEENTHOMPSON Northwestern University Medical General Electric Company, Sun Jose, California School, Chicago, Illinois President-Elect HELENEDECHIEF DR. F. E. MCKENNA Canadian National Railways, Air Reduction Company, Inc., Murray Hill, New Iersey Montreal, Quebec Advisory Council Chairman PHOEBEF. HAYES(Secretary) HERBERTS. WHITE Bibliographical Center for Re- NASA Facility, Documerztation, Inc., Bethesda, Maryland .tearch, Denver, Colorado Advisory Council Chairman-Elect KENNETHN. METCALF MRS. HELENF. REDMAN Henry Ford Museum and Green- Los Alamor Scientific Laboratou7, Los Alamos, New Mexico field Village, Dealborn, Michigan Treasurer RUTH NIELANDER JEAN E. FLEGAL Lumbermens Mutual Casudty Union Carbide Corp., New York, New Yolk Cumpany, Chicago, 1llinoi.r Immediate Past-President MRS. DOROTHYB. SKAU WILLIAMS. BUDINGTON Southern Regional Research Lab- The John Crerur Library, Chicago, Illinois oratory, US. Department of Agri- culture, Neu; Orlean.r, Louisiana EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: BILL M. -

ACRL News Issue (B) of College & Research Libraries

derson, David W. Heron, William Heuer, Peter ACRL Amendment Hiatt, Grace Hightower, Sr. Nora Hillery, Sam W. Hitt, Anna Hornak, Marie V. Hurley, James Defeated in Council G. Igoe, Mrs. Alice Ihrig, Robert K. Johnson, H. G. Johnston, Virginia Lacy Jones, Mary At the first meeting of the ACRL Board of Kahler, Frances Kennedy, Anne E. Kincaid, Directors on Monday evening, June 21, the Margaret M. Kinney, Thelma Knerr, John C. Committee on Academic Status made known Larsen, Mary E. Ledlie, Evelyn Levy, Joseph its serious reservations about the proposed Pro W. Lippincott, Helen Lockhart, John G. Lor gram of Action of the ALA Staff Committee on enz, Jean E. Lowrie, Robert R. McClarren, Jane Mediation, Arbitration and Inquiry. It moved S. McClure, Stanley McElderry, Jane A. Mc that the Board support an amendment to the Gregor, Elizabeth B. Mann, Marion A. Milc Program which would provide that the staff zewski, Eric Moon, Madel J. Morgan, Effie Lee committee “shall not have jurisdiction over mat Morris, Florrinell F. Morton, Margaret M. Mull, ters relating to the status and problems of aca William D. Murphy, William C. Myers, Mrs. demic librarians except on an interim basis,” Karl Neal, Mildred L. Nickel, Eileen F. Noo and that the interim should last only through nan, Philip S. Ogilvie, A. Chapman Parsons, August 31, 1972. It also stipulated that proce Richard Parsons, Anne Pellowski, Mary E. dures be set up by ACRL to protect the rights Phillips, Margaret E. Poarch, Patricia Pond, of academic librarians. (For the full amend Gary R. Purcell, David L. -

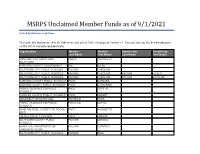

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds As of 4/30/2021

MSRPS Unclaimed Member Funds as of 9/1/2021 Sorted by Member Last Name To search this document, click the Edit menu and select Find, or just press Control + F. You can also use the Bookmarks pane on the left to navigate alphabetically. Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PABLA TARUNJEET BALTIMORE HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PAC ELLEN BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELISEO BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACANA CAROLINA PACANA ELIZALDE HARFORD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE BARBARA HOWARD COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE CATHERINE PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACE CRYSTAL SCHOOLS CHARLES COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PACE ROBERT UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND PACHECO ELVIA PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PACHECO MAYRA SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO DEPT OF SOCIAL PACK ANJENETTE SERV TALBOT COUNTY COUNCIL PACK LANARD BALTIMORE COUNTY PUBLIC PACKER AMANDA SCHOOLS MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF PACKER KIMBERLY TRANSPORTATION BALTIMORE CITY PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDER IRAM Organization Member Member Beneficiary Beneficiary Last Name First Name Last Name First Name PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK SCHOOLS PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADDOCK JACK PADDOCK LANDON SCHOOLS ANNE ARUNDEL CO PUBLIC SCHOOLS PADDY GLADYS PADDY CYNTHIA WESTERN MARYLAND HOSPITAL PADEN GLENNA PADEN HAROLD CENTER PRINCE GEORGES CO PUBLIC PADEN JENNIFER SCHOOLS WASHINGTON COUNTY PUBLIC PADEN JULIAN PADEN MARY SCHOOLS TOWN OF CHEVERLY PADGETT MATTHEW HARFORD COUNTY GOVERNMENT PADGETT TIFFANY