Report Referenced by Karen Cheney

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Homelessness Prevention Strategy 2018

Wolverhampton WV1 1SH City of Wolverhampton Council, Civic Centre, St. Peter’s Square, St.Peter’s Council,Civic Centre, City ofWolverhampton wolverhampton. audio orinanotherlanguagebycalling01902 551155 You can get this information in large print, braille, WolverhamptonToday Wolverhampton_Today @WolvesCouncil gov.uk gov.uk 01902 551155 WCC 1875 05/2019 wolverhampton. andIntervention #Prevention 2018 -2022 Strategy Prevention Homelessness Chapter title gov.uk Contents Foreword Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Development of the strategy 6 Defining Homelessness 6 National Context 7 Homelessness Data 8 Homelessness Prevention and Relief 9 UK Government Priorities 10 West Midlands Combined Authority 11 Local Context 12 Since the publication of our last Homelessness Strategy, we have seen dramatic changes to the Demographic Data 13 environment in which homelessness services are delivered. Changes resulting from the economic downturn, and in particular welfare reform, are impacting Under One Roof 13 detrimentally on many low- income groups and those susceptible to homelessness. Well documented Strategic Context 15 funding cuts to Councils are coupled with falls in support and funding streams to other statutory agencies, and those in the voluntary and community sector. Homelessness Strategy 2018-2022 16 As a result, this new strategy is being developed in a context of shrinking resources and increasing demand for services. There is also considerable uncertainty over the future. Homelessness prevention 16 These factors weigh heavily on the determination of what can realistically be achieved in the years Rough Sleepers 18 ahead. Nevertheless, the challenge and our aspiration remains to prevent homelessness wherever possible in line with the new Homelessness Reduction Act. Vulnerability and Health 19 The response to this challenge will be based on the same core principle as that which underpinned Vulnerabilities 20 our previous strategies effective partnership working. -

Staffordshire County Council 5 Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council 1 Sandwell 1 Wolverhampton City Council 1 Stoke on Trent Ci

Staffordshire County Council 5 Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council 1 Sandwell 1 Wolverhampton City Council 1 Stoke on Trent City Council 1 Derby City Council 3 Nottinghamshire County Council 2 Education Otherwise 2 Shropshire County Council 1 Hull City Council 1 Warwickshire County Council 3 WMCESTC 1 Birmingham City Council 1 Herefordshire County Council 1 Worcestershire Childrens Services 1 Essex County Council 1 Cheshire County Council 2 Bedfordshire County Council 1 Hampshire County Council 1 Telford and Wrekin Council 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Education Everywhere 1 Derbyshire County Council 1 Jun-08 Cheshire County Council 3 Derby City Travellers Education Team 2 Derbyshire LA 1 Education Everywhere 1 Staffordshire County Council 6 Essex County Council 1 Gloustershire County Council 1 Lancashire Education Inclusion Service 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Nottingham City 1 Oxford Open Learning Trust 1 Shropshire County Council 1 Solihull Council 2 Stoke on Trent LA 1 Telford and Wrekin Authority 2 Warwickshire County Council 4 West Midlands Consortium Education Service 1 West Midlands Regional Partnership 1 Wolverhampton LA 1 Nov-08 Birmingham City Council 2 Cheshire County Council 3 Childline West Midlands 1 Derby City LA 2 Derby City Travellers Education Team 1 Dudley LA 1 Education At Home 1 Education Everywhere 1 Education Otherwise 2 Essex County Council 1 Gloucestershire County Council 2 Lancashire Education Inclusion Service 1 Leicestershire County Council 1 Nottinghamshire LA 2 SERCO 1 Shropshire County Council -

Birmingham City Council (Appellants) V Ali (FC) and Others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) V Manchester City Council (Respondents)

HOUSE OF LORDS SESSION 2008–09 [2009] UKHL 36 on appeal from: [2008]EWCA Civ 1228 [2008]EWCA Civ 378 OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Birmingham City Council (Appellants) v Ali (FC) and others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) v Manchester City Council (Respondents) Appellate Committee Lord Hope of Craighead Lord Scott of Foscote Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe Baroness Hale of Richmond Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury Counsel Appellant (Birmingham City Council): Respondent: (Ali): Ashley Underwood QC Jan Luba QC Catherine Rowlands Zia Nabi (Instructed by Birmingham City Council) (Instructed by Community Law Partnership) Appellant: (Moran): Respondent (Manchester City Council): Jan Luba QC Clive Freedman QC Adam Fullwood Zoe Thompson (Instructed by Shelter Greater Manchester Housing (Instructed by Manchester City Council) Centre ) Interveners: Secretary of State for Communities and Interveners: Women’s Aid Federation: Local Government: Stephen Knafler Martin Chamberlain Liz Davies (Instructed by Treasury Solicitors) (Instructed by Sternberg Reed ) Hearing dates: 26 JANUARY, 28 and 29 APRIL 2009 ON WEDNESDAY 1 JULY 2009 HOUSE OF LORDS OPINIONS OF THE LORDS OF APPEAL FOR JUDGMENT IN THE CAUSE Birmingham City Council (Appellants) v Ali (FC) and others (FC) (Respondents) Moran (FC) (Appellant) v Manchester City Council (Respondents) [2009] UKHL 36 LORD HOPE OF CRAIGHEAD My Lords, 1. I have had the privilege of reading in draft the opinion which has been prepared by my noble and learned friend Baroness Hale of Richmond, to which my noble and learned friend Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury has contributed. I agree with it, and for the reasons they have given I would allow both appeals. -

Compensation Claims Against Local Authorities

Compensation claims against local authorities Harry Fairhead Policy Analyst, TaxPayers’ Alliance January 2016 his research paper looks at compensation claims made against local authorities in England, Scotland and Wales in 2013-14 and 2014-15. It gives details of payments made by the T authority or its insurers (including outstanding estimates) as well as details of the claim. Where the authority has paid out or made an excess payment there is a direct cost to taxpayers. Where the insurer has paid out this will be reflected in higher premiums for the authority and greater cost to the taxpayer. The key findings of this research are: • Over £104 million was paid out in compensation in 2013-14 and 2014-15. • There were more than 40,000 compensation claims paid out in 2013-14 and 2014-15. • Claim details and payments are available for all local authorities. Full data tables can be downloaded by clicking here • The London Borough with the most paid out was Lambeth with £5,264,071 • The Scottish Council with the most paid out was City of Glasgow with £2,735,960 • The Metropolitan district with the most paid out was Manchester City Council with £5,119,419 • The Non-metropolitan district with the most paid out was Basildon District Council with £1,588,443 • The Unitary council with the most paid out was Luton Borough Council with £1,910,260 • The Welsh Council with the greatest total claims (including outstanding estimates) was Vale of Glamorgan with £1,120,528 • The County Council with the most paid out was Norfolk County Council with £3,474,123 Financial support for this research paper was provided by the Politics and Economics Research Trust (charity number 1121849). -

Mifriendly Cities – Migration Friendly Cities Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton 2017/18-2020/21

MiFriendly Cities – Migration Friendly Cities Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton 2017/18-2020/21 Summary In partnership with Coventry City and Wolverhampton City Councils, Birmingham City Council has been successful in securing EU funding to deliver a three year MiFriendly Cities project. The project, which is backed by West Midlands Combined Authority, will see the three Councils working together to develop new and innovative activity which can help integrate economic migrants, refugees and asylum seekers into the West Midlands. This approach provides an opportunity for Birmingham City Council to explore how it can work with partners and migrants in a way which can help to expand the current range of activity, which mostly focuses on addressing the basic needs and legal rights of migrants. As part of this approach there is a particular focus on changing attitudes to migrants, developing employment pathways, social enterprise and active citizenship. Coventry City Council will be managing the whole project but Birmingham City Council will be required to project manage and coordinate activity which specifically relates to Birmingham, across all the different work packages and activities. Birmingham has also been asked to lead the regional work on “Active Citizenship”. Introduction Following a competitive bidding process “MiFriendly Cities” was chosen by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) as one of three projects across Europe which they would like to support. This was from two hundred proposals which were submitted. To support the delivery of the MiFriendly Cities project the EU is providing €4,280,640 over three years to Birmingham, Coventry and Wolverhampton City Councils. This is irrespective of the Brexit process and the UK leaving the EU in 2019. -

City of Wakefield Metropolitan District Council

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL REPORT OF INTERIM ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF REGULATION AND ENFORCEMENT TO THE LICENSING AND PUBLIC PROTECTION COMMITTEE DECEMBER 2020 13 JANUARY 2020 ALL WARDS AFFECTED Birmingham City Council hosted ENGLAND ILLEGAL MONEY LENDING TEAM 1. Summary 1.1 This report provides an update on the work of the England Illegal Money Lending Team (IMLT) hosted by Birmingham City Council’s, Regulation and Enforcement Division at 30 November 2020 2. Recommendation 2.1 That the report be noted. Contact Officer: Paul Lankester, Interim Assistant Director, Regulation and Enforcement Telephone: 0121 675 2495 Email: [email protected] Originating Officer: Tony Quigley, Head of Service 1 3. Background 3.1 The grant funded project was initially piloted in 2004 with teams from Birmingham and Glasgow operating across a specific region. The purpose was to identify if illegal money lending was in operation and, if so, investigate and institute proceedings against those involved. The project was commissioned for an initial period of two years. It was further extended year to year following a number of high profile successful investigations. 3.2 There is also a national team covering Scotland, Wales and teams covering Northern Ireland. All of the teams regurlarly hold meeting, currently virtual, to share best practice and current innitiatives. 3.3 The IMLT operates across the country using legislative powers under the Consumer Rights Act 2015. 3.4 The brief of the IMLT, from its inception, has been to investigate and prosecute illegal money lenders and to provide support to victims and communities under the control of illegal money lenders and by working with partner agencies to deliver this support. -

City Council Meeting Inquiry of the Co-Ordinating O&S Committee

City Council Meeting Inquiry of the Co-ordinating O&S Committee 1 Purpose 1.1 One of the recommendations in the Review of Scrutiny, agreed by City Council in March 2018, was that an inquiry into the role and purpose of the full City Council meeting was held. The Co- ordinating agreed to undertake this inquiry at its last meeting and to review the arrangements for City Council meetings. 1.2 A draft terms of reference are appended for the Committee to agree (Appendix 1), which have several lines of enquiry: Understand the statutory requirements and responsibilities of full Council and its role in decision-making in the council; Review Standing Orders to ensure they are fit for purpose; Consider whether the agenda items properly reflect the responsibilities of the council at all levels – from regional to local level; Review the operation of the meetings – the timings, the formalities and use of technology – to ensure it is fit for purpose; Explore the role of Council Business Management Committee (CBM) in supporting Council in non-Executive functions; Explore the role City Council plays in local democracy and public engagement. 1.3 This note sets out some background information and key questions for each area. 2 Previous Reviews of the City Council Process 2.1 The note below includes some findings from previous inquiries and from a recent officer review of the processes associated with the City Council meeting. 2.2 In 2005, the Co-ordinating O&S Committee conducted a review of the Role of Members and the Full Council. The report can be found at: https://www.birmingham.gov.uk/downloads/file/507/role_of_members_at_full_council_scrutiny _report_april_2005pdf . -

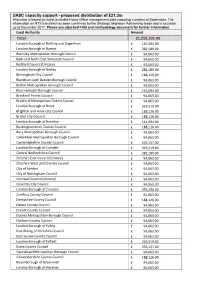

UASC Capacity Support - Proposed Distribution of £21.3M Allocation Is Based on Latest Available Home Office Management Data Capturing Numbers at September

UASC capacity support - proposed distribution of £21.3m Allocation is based on latest available Home Office management data capturing numbers at September. The information on NTS transfers has been confirmed by the Strategic Migration Partnership leads and is accurate up to December 2017. Please see attached FAQ and methodology document for further information. Local Authority Amount Total 21,258,203.00 London Borough of Barking and Dagenham £ 141,094.00 London Borough of Barnet £ 282,189.00 Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bath and North East Somerset Council £ 94,063.00 Bedford Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Bexley £ 282,189.00 Birmingham City Council £ 188,126.00 Blackburn with Darwen Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bolton Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Bournemouth Borough Council £ 141,094.00 Bracknell Forest Council £ 94,063.00 Bradford Metropolitan District Council £ 94,063.00 London Borough of Brent £ 329,219.00 Brighton and Hove City Council £ 188,126.00 Bristol City Council £ 188,126.00 London Borough of Bromley £ 141,094.00 Buckinghamshire County Council £ 188,126.00 Bury Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council £ 94,063.00 Cambridgeshire County Council £ 235,157.00 London Borough of Camden £ 329,219.00 Central Bedfordshire Council £ 282,189.00 Cheshire East Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Cheshire West and Chester Council £ 94,063.00 City of London £ 94,063.00 City of Nottingham Council £ 94,063.00 Cornwall Council (Unitary) £ 94,063.00 Coventry City -

INLOGOV Independent Review of BCC Financial Position

Birmingham Business School Institute of Local Government Studies Independent review of the financial position of Birmingham City Council Report August 2012 INLOGOV, University of Birmingham Independent Review of the Financial Position of Birmingham City Council: Report The Institute of Local Government Studies (INLOGOV), University of Birmingham CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................... 3 The National Context .................................................................................... 3 Birmingham City Council’s Financial Position ............................................... 6 Future Risks .................................................................................................. 8 Equal Pay................................................................................................... 8 Reserves .................................................................................................... 8 Closing the Funding Gap ........................................................................... 9 Borrowing ................................................................................................. 11 Income from Council Tax ......................................................................... 12 Council Tax Benefit .................................................................................. 12 Business Rates Retention ........................................................................ 13 Accounting Issues ................................................................................... -

Download (15Mb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36386 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. WOMEN, FINANCE AND CREDIT IN ENGLAND, c. 1780-1826 Christine Wiskin Submitted in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History at the University of Warwick June 2000 Contents List of illustrations 1 List of maps 11 List of tables 111 List of figures lv Acknowledgments V Abstract vi List of abbreviations vii Chapter 1 Introduction Concepts of women and credit 1 Sources and methods ii Historiography 22 New directions 30 'A history of industrial possibility' 44 Chapter 2 The Economy of the West Midlands in the Eighteenth Century Characteristics of the region 49 Cash and credit in the region 63 Small-scale capitalism 82 Contrasts, complexity and change 88 Chapter 3 Women in business, c. 1780-1826 Industrious independence 92 Businesswomen as managers 113 The impact of change 119 Reputation and respectability 128 Businesswomen in industrialising England 144 Chapter 4 Businesswomen and entrepreneurial networks The membership of networks 147 Trust and prudence 171 Some benefits of membership 180 Reconsidering entrepreneurial networks 190 Chapter 5 Women -

Video Transcript Artist: Tanya Raabe-‐Webber Sitter

Portraits Untold – Video Transcript Artist: Tanya Raabe-Webber Sitter: John Akomfrah Venue: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery Date Saturday 16th July 2016 Ambitious live portrait project with artist Tanya Raabe-Webber, exploring and celebrating our common humanity – the beauty and strength of humanity lies in the diversity of its people. This stream features artist and filmmaker John Akomfrah - more information can be found at - http://portraitsuntold.co.uk/sittings... This video stream was filmed at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery (BMAG) on Saturday 16th July 2016. The second sitting will feature Dame Evelyn Glennie at the National Portrait Gallery on Friday 22nd July 2016 - more information can be found at http://portraitsuntold.co.uk/sittings... Take part by contributing your drawing via Facebook, twitter and Instagram and tagging #PortraitsUntold http://portraitsuntold.co.uk/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/PortraitsUntold Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PortraitsUntold Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/PortraitsUn... Supported using public funding by the National Lottery through Arts Council England. #PortraitsUntold [Transcript Starts] Tom Dipple, BMAG: Thank you for coming Tom Dipple, BMAG: I'm a learning manager for the museum. Tom Dipple, BMAG: Welcome to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery. Tom Dipple, BMAG: Birmingham Museum's trust is proud to be hosting Portraits Untold. Tom Dipple, BMAG: We are honoured and excited Tom Dipple, BMAG: The project aims are similar to our own Tom Dipple, BMAG: We hope to grow diverse audiences Tom Dipple, BMAG: and make Birmingham a focus for contemporary art. Tom Dipple, BMAG: By welcoming artists and others, we can promote diversity and culture of Birmingham Mandy, Project Producer: Thank you to BMAG for hosting our first Portraits Untold project Mandy, Project Producer: While this is national, the partners are midlands based, Mandy, Project Producer: Thanks to Arts Council, for funding and officers' help.