Collectivization, Participation and Dissidence on the Transatlantic Axis During the Cold War: Cultural Guerrilla for Destabilizing the Balance of Power in the 1960S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copertina Artepd.Cdr

Trent’anni di chiavi di lettura Siamo arrivati ai trent’anni, quindi siamo in quell’età in cui ci sentiamo maturi senza esserlo del tutto e abbiamo tantissime energie da spendere per il futuro. Sono energie positive, che vengono dal sostegno e dal riconoscimento che il cammino fin qui percorso per far crescere ArtePadova da quella piccola edizio- ne inaugurale del 1990, ci sta portando nella giusta direzione. Siamo qui a rap- presentare in campo nazionale, al meglio per le nostre forze, un settore difficile per il quale non è ammessa l’improvvisazione, ma serve la politica dei piccoli passi; siamo qui a dimostrare con i dati di questa edizione del 2019, che siamo stati seguiti con apprezzamento da un numero crescente di galleristi, di artisti, di appassionati cultori dell’arte. E possiamo anche dire, con un po’ di vanto, che negli anni abbiamo dato il nostro contributo di conoscenza per diffondere tra giovani e meno giovani l’amore per l’arte moderna: a volte snobbata, a volte non compresa, ma sempre motivo di dibattito e di curiosità. Un tentativo questo che da qualche tempo stiamo incentivando con l’apertura ai giovani artisti pro- ponendo anche un’arte accessibile a tutte le tasche: tanto che nei nostri spazi figurano, democraticamente fianco a fianco, opere da decine di migliaia di euro di valore ed altre che si fermano a poche centinaia di euro. Se abbiamo attraversato indenni il confine tra due secoli con le sue crisi, è per- ché l’arte è sì bene rifugio, ma sostanzialmente rappresenta il bello, dimostra che l’uomo è capace di grandi azzardi e di mettersi sempre in gioco sperimen- tando forme nuove di espressione; l’arte è tecnica e insieme fantasia, ovvero un connubio unico e per questo quasi magico tra terra e cielo. -

Jcmac.Art W: Jcmac.Art Hours: T-F 10:30AM-5PM S 11AM-4PM

THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Above: Carmelo Arden Quin, Móvil, 1949. 30 x 87 x 95 in. Cover: Alejandro Otero, Coloritmo 75, 1960. 59.06 x 15.75 x 1.94 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection 3 Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection was founded in 2005 out of a passion for art and a commitment to deepen our understanding of the abstract-geometric style as a significant part of Latin America’s cultural legacy. The fascinating revolutionary visual statements put forth by artists like Jesús Soto, Lygia Clark, Joaquín Torres-García and Tomás Maldonado directed our investigations not only into Latin American regions but throughout Europe and the United States as well, enriching our survey by revealing complex interconnections that assert the geometric genre's wide relevance. It is with great pleasure that we present The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection celebrating the recent opening of Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection’s new home among the thriving community of cultural organizations based in Miami. We look forward to bringing about meaningful dialogues and connections by contributing our own survey of the intricate histories of Latin American art. Juan Carlos Maldonado Founding President Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection Left: Juan Melé, Invención No.58, 1953. 22.06 x 25.81 in. (detail) THE UNBOUNDED LINE The Unbounded Line A Selection from the Juan Carlos Maldonado Art Collection explores how artists across different geographical and periodical contexts evaluated the nature of art and its place in the world through the pictorial language of geometric abstraction. -

Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy (Exhibition Catalogue)

KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. KINETIC MASTERS & THEIR LEGACY OCTOBER 3, 2019 - JANUARY 11, 2020 CECILIA DE TORRES, LTD. We are grateful to María Inés Sicardi and the Sicardi-Ayers-Bacino Gallery team for their collaboration and assistance in realizing this exhibition. We sincerely thank the lenders who understood our desire to present work of the highest quality, and special thanks to our colleague Debbie Frydman whose suggestion to further explore kineticism resulted in Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy. LE MOUVEMENT - KINETIC ART INTO THE 21ST CENTURY In 1950s France, there was an active interaction and artistic exchange between the country’s capital and South America. Vasarely and many Alexander Calder put it so beautifully when he said: “Just as one composes colors, or forms, of the Grupo Madí artists had an exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires in 1957 so one can compose motions.” that was extremely influential upon younger generation avant-garde artists. Many South Americans, such as the triumvirate of Venezuelan Kinetic Masters & Their Legacy is comprised of a selection of works created by South American artists ranging from the 1950s to the present day. In showing contemporary cinetismo–Jesús Rafael Soto, Carlos Cruz-Diez, pieces alongside mid-century modern work, our exhibition provides an account of and Alejandro Otero—settled in Paris, amongst the trajectory of varied techniques, theoretical approaches, and materials that have a number of other artists from Argentina, Brazil, evolved across the legacy of the field of Kinetic Art. Venezuela, and Uruguay, who exhibited at the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. -

Aperto Geometrismo E Movimento

Aperto BOLLETTINO DEL GABINETTO DEI DISEGNI E DELLE STAMPE NUMERO 4, 2017 DELLA PINACOTECA NAZIONALE DI BOLOGNA aperto.pinacotecabologna.beniculturali.it Geometrismo e movimento Elisa Baldini Tendenze non figurative di orientamento geometrizzante si affermano in Europa nel secondo dopoguerra. La ricerca della purezza formale contraddistingue il nuovo internazionalismo estetico così come l’attenzione al design e alla “sintesi delle arti”. Erede di una sensibilità determinatasi intorno alla metà del secolo precedente, la propensione dell’arte a confrontarsi con le scoperte scientifiche e tecnologiche è caratteristica determinante della attitudine astrattista di questo periodo e mira a superare la tradizionale dicotomia che contrappone arte e scienza, conducendo la prima sul sentiero della regola armonica e del dominio dell’esattezza. Sopravanzando gli esiti delle ricerche astrattiste delle avanguardie di inizio Novecento, che mantenevano una referenzialità con il mondo fenomenico, l’astrazione alla quale gli artisti del secondo dopoguerra fanno riferimento discende dal pensiero concretista di Theo van Doesburg e i suoi esiti contestano tanto la figurazione quanto l’astrazione lirica. All’esistenzialismo informale che aveva dominato la decade precedente le composite sperimentazioni neoconcrete oppongono la necessità di investigare le ragioni oggettive della vista e della percezione. È così che, in molti casi, la grafica evidenzia la necessità degli autori di esplorare con mezzi diversi le poetiche che caratterizzano le loro ricerche. È il caso di Auguste Herbin (1882 – 1960) che in Composizione astratta (Minuit) del 1959 (Tip. 29813) traduce, senza difficoltà alcuna, la sua pittura, fatta di semplici figure geometriche dai colori puri stesi con grandi pennellate piatte, in serigrafia, mezzo peraltro congeniale a dare risalto al contrasto armonico tra sfondo e figure, caratteristica tipica della ricerca di Herbin fin dagli anni Trenta1. -

Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 the Continent That the EU Does Not Know

Art in Europe 1945 Art in — 1968 The Continent EU Does that the Not Know 1968 The The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Art in Europe 1945 — 1968 Supplement to the exhibition catalogue Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Phase 1: Phase 2: Phase 3: Trauma and Remembrance Abstraction The Crisis of Easel Painting Trauma and Remembrance Art Informel and Tachism – Material Painting – 33 Gestures of Abstraction The Painting as an Object 43 49 The Cold War 39 Arte Povera as an Artistic Guerilla Tactic 53 Phase 6: Phase 7: Phase 8: New Visions and Tendencies New Forms of Interactivity Action Art Kinetic, Optical, and Light Art – The Audience as Performer The Artist as Performer The Reality of Movement, 101 105 the Viewer, and Light 73 New Visions 81 Neo-Constructivism 85 New Tendencies 89 Cybernetics and Computer Art – From Design to Programming 94 Visionary Architecture 97 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know Introduction Praga Magica PETER WEIBEL MICHAEL BIELICKY 5 29 Phase 4: Phase 5: The Destruction of the From Representation Means of Representation to Reality The Destruction of the Means Nouveau Réalisme – of Representation A Dialog with the Real Things 57 61 Pop Art in the East and West 68 Phase 9: Phase 10: Conceptual Art Media Art The Concept of Image as From Space-based Concept Script to Time-based Imagery 115 121 Art in Europe 1945 – 1968. The Continent that the EU Does Not Know ZKM_Atria 1+2 October 22, 2016 – January 29, 2017 4 At the initiative of the State Museum Exhibition Introduction Center ROSIZO and the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow, the institutions of the Center for Fine Arts Brussels (BOZAR), the Pushkin Museum, and ROSIZIO planned and organized the major exhibition Art in Europe 1945–1968 in collaboration with the ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. -

VALERIO ADAMI Diario Del Lago

VALERIO ADAMI Diario del lago a cura di Vera Agosti CITTA’ DI CANNOBIO PALAZZO PARASI La Città di Cannobio con la personale di Valerio Adami, “Diario del Lago”, prosegue il percorso delle mostre a Palazzo Parasi, confermando così la ferma intenzione di dare ampio spazio alla promozione culturale sotto le più varie forme. Le lodi molto lusinghiere che abbiamo ricevuto per il fatto di riuscire, pur essendo Cannobio una piccola realtà, a realizzare progetti di grande rilevanza culturale che hanno avuto eco all’interno dei luoghi frequentati da specialisti del settore dell’arte, ci spronano a continuare lungo il percorso intrapreso. Valerio Adami, maestro colto e raffinato dell’arte contemporanea mondiale, impreziosisce ulteriormente con la sua presenza questo nostro progetto. Da sempre consacrato alla figurazione, racconta “l’uomo sociale d’oggi”. Lui stesso spiega: “Dipingo in prosa ma qualche rima scappa via”. Attraverso il mezzo privilegiato della linea e usando colori piatti e antinaturalistici, l’artista crea composizioni movimentate su più piani, enigmatiche ed intriganti. Con il maestro Adami Cannobio intende offrire ai cittadini ed ai numerosi ospiti italiani e stranieri un’opportunità culturale di altissimo livello che si estenderà, attraverso il percorso lungo la naturale via del Lago, fino a Ghiffa, all’interno dello spazio espositivo del Brunitoio, dove si svolgerà una mostra di Grafiche dello stesso autore. Rivolgiamo i nostri sinceri ringraziamenti alla curatrice Vera Agosti, che con la grande passione che la contraddistingue, ha contribuito alla realizzazione del progetto; alla Galleria Tega di Milano che, credendo in questo importante impegno, ha messo a disposizione molte delle opere esposte. -

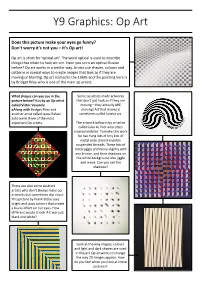

Y9 Graphics: Op Art

Y9 Graphics: Op Art Does this picture make your eyes go funny? Don't worry it's not you – it's Op art! Op art is short for 'optical art'. The word optical is used to describe things that relate to how we see. Have you seen an optical Illusion before? Op art works in a similar way. Artists use shapes, colours and patterns in special ways to create images that look as if they are moving or blurring. Op art started in the 1960s and the painting here is by Bridget Riley who is one of the main op artists. What shapes can you see in the Some op artists made artworks picture below? It is by an Op artist that don't just look as if they are called Victor Vasarely. moving – they actually ARE aAlong with Bridget Riley and moving! Art that moves is another artist called Jesus Rafael sometimes called kinetic art. Soto were three of the most important Op artists. The artwork below is by an artist called Julio Le Parc who often created mobiles. To make this work he has hung lots of tiny bits of metal onto almost invisible suspended threads. These bits of metal jiggle and move slightly with any breeze, and their shadows on the white background also jiggle and move. Can you see the shadows? There are also some abstract artists who don't always make op artworks but sometimes slip into it. This picture by Frank Stella uses bright and jazzy colours that create a buzzy effect on our eyes. -

Download Document

Josef Albers Max Bill Piero Dorazio Manuel Espinosa Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart Manuel Espinosa in Europe Josef Albers Max Bill Piero Dorazio Manuel Espinosa Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart Frieze Masters 2019 - Stand E7 Manuel Espinosa and his European Grand Tour Dr. Flavia Frigeri Once upon a time, it was fashionable among young members of the British and northern European upper classes to embark on what came to be known as the Grand Tour. A rite of passage of sorts, the Grand Tour was predicated on the exploration of classical antiquity and Renaissance masterpieces encountered on a pilgrimage extending from France all the way to Greece. Underpinning this journey of discovery was a sense of cultural elevation, which in turn fostered a revival of classical ideals and gave birth to an international network of artists and thinkers. The Grand Tour reached its apex in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, after which interest in the great classical beauties of France, Italy and Greece slowly waned.1 Fast-forward to 1951, the year in which the Argentine artist Manuel Espinosa left his native Buenos Aires to embark on his own Grand Tour of Europe. Unlike his cultural forefathers, Espinosa was not lured by 4 Fig. 1 Founding members of the Concrete-Invention Art Association pictured in 1946. Espinosa is third from the right, back row. Photo: Saderman. the qualities of classical and Renaissance Europe, but what propelled him to cross an ocean and spend an extended period of time away from home was the need to establish a dialogue with his abstract-concrete European peers. -

Valerio Adami

VALERIO ADAMI Valerio Adami, La valle del petrolio, 1964, oil on canvas, 180 x 140 cm. Photo: Filippo Armellin, Courtesy: Fondazione Marconi, Milano July 1 – August 28, 2016 Opening: April 21, 2016, 7 p.m. Press conference: April 20, 2016, 10 a.m. The painter and illustrator Valerio Adami is widely regarded as an eminent representative of Italian Pop art. His exhibition in the Secession’s Grafisches Kabinett is the artist’s first solo show in Austria and showcases a series of paintings from his less well-known early oeuvre. Created before 1964, these works stand out for the particularly dynamic interplay between expressive abstraction and stylized figuration. Explosive discharges of energy are the dominant motif in the selected starkly simplified depictions. Adami’s pictorial spaces teem with bodies wrestling with each other and objects being blown to a thousand pieces, with energy fields, cosmic rays, fire, and dense clouds of smoke. Interspersed between them like quotations lifted from a cartoon are speech bubbles and onomatopoetic words signaling the pictures’ pop and bang. The characteristic features of Adami’s work from this time are the evolution of many of his forms out of the graphical gesture and the painterly structure he lends to different surfaces, probing the ostensible contradiction between individual emotional expression and a deadpan delivery devoid of subjective inflections with almost effortless ease. Starting in 1964, Valerio Adami’s visual language developed in a fundamentally new direction. The temperamental graphical hand that thrills in his earlier works recedes in favor of a new style defined by elemental and clearly contoured shapes and areas of flatly even paint. -

Valerio Adami Solo Exhibitions

VALERIO ADAMI Born in 1935 in Bologna, Italy Lives and works between Paris, Monte Carlo and Meina, Italy SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION) 2019 Camilla et Valerio Adami, Espace Jacques Villeglé, Saint Gratien, France The 80s, Galerie Templon, Paris, France 2018 Adami : lignes de vie, Musée Jean Cocteau, Collection Séverin Wunderman, Menton, France 2017 Valerio Adami, Galleria L'Incontro, Chiari, Bs, Italy Valerio Adami - The Narrative Line, The Mayor Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2016 Valerio Adami, Secession, Vienna, Austria Transfigurations, Chapelle Saint-Sauveur, Saint-Malo, France De la ligne à la couleur, Le Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, Issoudun, France Valerio Adami, Galerie Daniel Templon Brussels, Brussels, Belgium Valerio Adami, Fondazione Marconi, Milan, Italy 2015 Great retrospective Valerio Adami’s 80th birthday, Turin Museum, Turin, Italy ; Mantua Museum, Mantua, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art contemporain à cent mètres du centre du monde, Perpignan, France 2014 Valerio Adami, Disegnare, Dipingere, Galeria André, Roma, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art graphique de la Métairie Bruyère, Parly, France 2013 Mosaïques, Ravenna Museum of Art, Ravenna, Italy Valerio Adami, Aquarelles, Galerie Biasutti, Turin, Italy 2012 Tableaux et dessins, Galerie Hass Ag, Zürich, Switzerland New Painting – Photographic Work from the Sixties, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, France Figure nel tempo, Galleria Tega, Milan, Italy Œuvres graphiques, Nev, Ankara, Turkey Valerio Adami, les années 1960, Galerie Laurent Strouk, Paris, France 2011 Quadri -

Julio Le Parc

GALERIE BUGADA & CARGNEL PARIS JULIO LE PARC Hall 2.0, stand G12 1 Julio Le Parc with Continuel-Lumière Cylindre in 1962 On the cover: Julio Le Parc with Continuel-Lumière Cylindre 1962 - 2012 wood, plexiglas, motor, light bulb 510 x 460 x 140 cm exhibition view, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, 2013 2 JULIO LE PARC “Generally speaking, I have tried, Historic figure and committed artist, Julio Le Parc (b. 1928) is a major figure through my experiments, to elicit a in Op and Kinetic art, founding member of G.R.A.V. (Groupe de Recherche different type of behavior from the d’Art Visuel, or Visual Art Research Group) and recipient of the Grand Prize for viewer […] to seek, together with the Painting at the 1966 Venice Biennale. This socially conscious artist was expelled public, various means of fighting off from France after the events of May 1968. A defender of human rights, he passivity, dependency or ideological fought against dictatorship in Latin America. In 1972, when the Musée d’Art conditioning, by developing reflective, Moderne de la Ville de Paris offered him a large retrospective, Le Parc decided comparative, analytical, creative whether or not to accept by flipping a coin: the exhibition did not take place. or active capacities.” Julio Le Parc Julio Le Parc creates interactive, social art. More than a mere play of light and shapes, his works are activated by the viewer’s physical interac- tion: movements of the retina, of the body, activate paintings, sculptures and installations that, as the artist insists, seek to “elicit a different behavior from the spectator […] and try to search alongside the public for the means of combating passivity, dependence or ideological conditioning, and to develop capacities for reflection, comparison, analysis, creation and action.” Particularly explorative of the spectator’s role, the artist creates work that is, in his own words, both interactive and unstable. -

Digimag43.Pdf

DIGICULT Digital Art, Design & Culture Founder & Editor-in-chief: Marco Mancuso Advisory Board: Marco Mancuso, Lucrezia Cippitelli, Claudia D'Alonzo Publisher: Associazione Culturale Digicult Largo Murani 4, 20133 Milan (Italy) http://www.digicult.it Editorial Press registered at Milan Court, number N°240 of 10/04/06. ISSN Code: 2037-2256 Licenses: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs - Creative Commons 2.5 Italy (CC BY- NC-ND 2.5) Printed and distributed by Lulu.com E-publishing development: Loretta Borrelli Cover design: Eva Scaini Digicult is part of the The Leonardo Organizational Member Program TABLE OF CONTENTS Marco Mancuso Exploding Cave ............................................................................................................. 3 Marco Mancuso Alain Thibault: Elektra From Past To The Future .................................................... 9 Motor Material Hybridization ................................................................................................ 15 Marco Riciputi The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button .................................................................... 21 Matteo Milani Valerio Adami And The Pictorial Sound ................................................................. 24 Marco Mancuso Esther Manas and Arash Moori: Sound and Sculpture ........................................ 29 Clemente Pestelli Giacomo Verde: Action Beyond Representation ................................................. 36 Silvia Casini Marc Didou: Resonances ..........................................................................................