<Xref Ref-Type="Transliteration" Rid="Trans12" Ptype

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VALERIO ADAMI Diario Del Lago

VALERIO ADAMI Diario del lago a cura di Vera Agosti CITTA’ DI CANNOBIO PALAZZO PARASI La Città di Cannobio con la personale di Valerio Adami, “Diario del Lago”, prosegue il percorso delle mostre a Palazzo Parasi, confermando così la ferma intenzione di dare ampio spazio alla promozione culturale sotto le più varie forme. Le lodi molto lusinghiere che abbiamo ricevuto per il fatto di riuscire, pur essendo Cannobio una piccola realtà, a realizzare progetti di grande rilevanza culturale che hanno avuto eco all’interno dei luoghi frequentati da specialisti del settore dell’arte, ci spronano a continuare lungo il percorso intrapreso. Valerio Adami, maestro colto e raffinato dell’arte contemporanea mondiale, impreziosisce ulteriormente con la sua presenza questo nostro progetto. Da sempre consacrato alla figurazione, racconta “l’uomo sociale d’oggi”. Lui stesso spiega: “Dipingo in prosa ma qualche rima scappa via”. Attraverso il mezzo privilegiato della linea e usando colori piatti e antinaturalistici, l’artista crea composizioni movimentate su più piani, enigmatiche ed intriganti. Con il maestro Adami Cannobio intende offrire ai cittadini ed ai numerosi ospiti italiani e stranieri un’opportunità culturale di altissimo livello che si estenderà, attraverso il percorso lungo la naturale via del Lago, fino a Ghiffa, all’interno dello spazio espositivo del Brunitoio, dove si svolgerà una mostra di Grafiche dello stesso autore. Rivolgiamo i nostri sinceri ringraziamenti alla curatrice Vera Agosti, che con la grande passione che la contraddistingue, ha contribuito alla realizzazione del progetto; alla Galleria Tega di Milano che, credendo in questo importante impegno, ha messo a disposizione molte delle opere esposte. -

Valerio Adami

VALERIO ADAMI Valerio Adami, La valle del petrolio, 1964, oil on canvas, 180 x 140 cm. Photo: Filippo Armellin, Courtesy: Fondazione Marconi, Milano July 1 – August 28, 2016 Opening: April 21, 2016, 7 p.m. Press conference: April 20, 2016, 10 a.m. The painter and illustrator Valerio Adami is widely regarded as an eminent representative of Italian Pop art. His exhibition in the Secession’s Grafisches Kabinett is the artist’s first solo show in Austria and showcases a series of paintings from his less well-known early oeuvre. Created before 1964, these works stand out for the particularly dynamic interplay between expressive abstraction and stylized figuration. Explosive discharges of energy are the dominant motif in the selected starkly simplified depictions. Adami’s pictorial spaces teem with bodies wrestling with each other and objects being blown to a thousand pieces, with energy fields, cosmic rays, fire, and dense clouds of smoke. Interspersed between them like quotations lifted from a cartoon are speech bubbles and onomatopoetic words signaling the pictures’ pop and bang. The characteristic features of Adami’s work from this time are the evolution of many of his forms out of the graphical gesture and the painterly structure he lends to different surfaces, probing the ostensible contradiction between individual emotional expression and a deadpan delivery devoid of subjective inflections with almost effortless ease. Starting in 1964, Valerio Adami’s visual language developed in a fundamentally new direction. The temperamental graphical hand that thrills in his earlier works recedes in favor of a new style defined by elemental and clearly contoured shapes and areas of flatly even paint. -

Valerio Adami Solo Exhibitions

VALERIO ADAMI Born in 1935 in Bologna, Italy Lives and works between Paris, Monte Carlo and Meina, Italy SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION) 2019 Camilla et Valerio Adami, Espace Jacques Villeglé, Saint Gratien, France The 80s, Galerie Templon, Paris, France 2018 Adami : lignes de vie, Musée Jean Cocteau, Collection Séverin Wunderman, Menton, France 2017 Valerio Adami, Galleria L'Incontro, Chiari, Bs, Italy Valerio Adami - The Narrative Line, The Mayor Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2016 Valerio Adami, Secession, Vienna, Austria Transfigurations, Chapelle Saint-Sauveur, Saint-Malo, France De la ligne à la couleur, Le Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch, Issoudun, France Valerio Adami, Galerie Daniel Templon Brussels, Brussels, Belgium Valerio Adami, Fondazione Marconi, Milan, Italy 2015 Great retrospective Valerio Adami’s 80th birthday, Turin Museum, Turin, Italy ; Mantua Museum, Mantua, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art contemporain à cent mètres du centre du monde, Perpignan, France 2014 Valerio Adami, Disegnare, Dipingere, Galeria André, Roma, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art graphique de la Métairie Bruyère, Parly, France 2013 Mosaïques, Ravenna Museum of Art, Ravenna, Italy Valerio Adami, Aquarelles, Galerie Biasutti, Turin, Italy 2012 Tableaux et dessins, Galerie Hass Ag, Zürich, Switzerland New Painting – Photographic Work from the Sixties, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, France Figure nel tempo, Galleria Tega, Milan, Italy Œuvres graphiques, Nev, Ankara, Turkey Valerio Adami, les années 1960, Galerie Laurent Strouk, Paris, France 2011 Quadri -

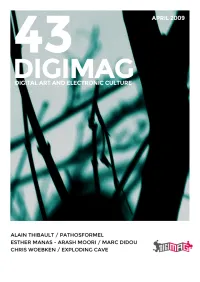

Digimag43.Pdf

DIGICULT Digital Art, Design & Culture Founder & Editor-in-chief: Marco Mancuso Advisory Board: Marco Mancuso, Lucrezia Cippitelli, Claudia D'Alonzo Publisher: Associazione Culturale Digicult Largo Murani 4, 20133 Milan (Italy) http://www.digicult.it Editorial Press registered at Milan Court, number N°240 of 10/04/06. ISSN Code: 2037-2256 Licenses: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs - Creative Commons 2.5 Italy (CC BY- NC-ND 2.5) Printed and distributed by Lulu.com E-publishing development: Loretta Borrelli Cover design: Eva Scaini Digicult is part of the The Leonardo Organizational Member Program TABLE OF CONTENTS Marco Mancuso Exploding Cave ............................................................................................................. 3 Marco Mancuso Alain Thibault: Elektra From Past To The Future .................................................... 9 Motor Material Hybridization ................................................................................................ 15 Marco Riciputi The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button .................................................................... 21 Matteo Milani Valerio Adami And The Pictorial Sound ................................................................. 24 Marco Mancuso Esther Manas and Arash Moori: Sound and Sculpture ........................................ 29 Clemente Pestelli Giacomo Verde: Action Beyond Representation ................................................. 36 Silvia Casini Marc Didou: Resonances .......................................................................................... -

2019 Camilla Et Valerio Adami, Espace Jacques Villeglé, Saint Gratien, France the 80S, Galerie Templon, Paris, France

SOLO EXHIBITIONS (SELECTION) 2019 Camilla et Valerio Adami, Espace Jacques Villeglé, Saint Gratien, France The 80s, Galerie Templon, Paris, France 2018 Adami : lignes de vie, Musée Jean Cocteau, Collection Séverin Wunderman, Menton, France 2017 Valerio Adami, Galleria L'Incontro, Chiari, Bs, Italy Valerio Adami - The Narrative Line, The Mayor Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2016 Valerio Adami, Secession, Vienna, Austria Transfigurations, Chapelle Saint-Sauveur, Saint-Malo, France De la ligne à la couleur, Le Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roche, Issoudun, France Valerio Adami, Galerie Daniel Templon Brussels, Brussels, Belgium Valerio Adami, Fondazione Marconi, Milan, Italy 2015 Great retrospective Valerio Adami’s 80th birthday, Turin Museum, Turin, Italy ; Mantua Museum, Mantua, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art contemporain à cent mètres du centre du monde, Perpignan, France 2014 Valerio Adami, Disegnare, Dipingere, Galeria André, Roma, Italy Valerio Adami, Centre d’art graphique de la Métairie Bruyère, Parly, France 2013 Mosaïques, Ravenna Museum of Art, Ravenna, Italy Valerio Adami, Aquarelles, Galerie Biasutti, Turin, Italy 2012 Tableaux et dessins, Galerie Hass Ag, Zürich, Switzerland New Painting – Photographic Work from the Sixties, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris, France Figure nel tempo, Galleria Tega, Milan, Italy Œuvres graphiques, Nev, Ankara, Turkey Valerio Adami, les années 1960, Galerie Laurent Strouk, Paris, France 2011 Quadri di lettura, Padiglione Italia, Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy Drawings, Galleria Usher arte, via della -

Jacques Derrida Thetruth in Painting

JACQUES DERRIDA THETRUTH IN PAINTING Translated by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1987 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1987 Printed in the United States of America 03 02 01 0099 98 97 9695 94 67 8 9 10 First published as LA VERITE EN PEINTURE in Paris, © 1978, Flammarion, Paris. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Derrida, Jacques. The truth in painting. Tr anslation of La verite en peinture. Includes index. I. Aesthetics. I. Title. BH39·D45 1987 701'.1'7 ISBN 0-2 2 6-143 24-4 (pbk.) Contents List of Illustrations vii Translators' Preface xiii Passe-Partout 1 1. Parergon 15 I. Lemmata 17 II. The Parergon 37 III. The Sans of the Pure Cut 83 IV. The Colossal 119 2. + R (Into the Bargain) 149 3. Cartouches 183 4. Restitutions 255 Index 383 List of Illustrations Parergon Johannes Kepler, De Nive Sexangula, printer's mark (photo, Flammarion) 25 Lucas Cranach, Lucretia, 1533, Berlin, Staatliche Museen Preus sische Kulturbesitz, Gemaldegalerie (photo, Wa lter Stein- kopf) 58 Antonio Fantuzzi, a cryptoportico, 1545 (photo, Flammarion) 60 Master L. D., cryptoporticQ of the grotto in the pinegarden, at Fontainebleau (photo, Flammarion) 62 Antonio Fantuzzi, ornamental panel with empty oval, 1542 - 43 (photo, Flammarion) 65 Antonio Fantuzzi, empty rectangular cartouche, 1544 - 45 (photo, Flammarion) 66 Doorframe, in the style of Louis XIV, anonymous engraving (photo, Roger Viollet) 72 Nicolas Robert, The Tu lip, in Tulia's Garland (photo, Girau- don) 86 Frontispiece to New Drawings of Ornaments, Panels, Carriages, Etc. -

PRESS RELEASE 7 March 2016 ITALIAN POP VALERIO ADAMI

Valerio Adami, Complet, 1970 Courtesy Tornabuoni Art PRESS RELEASE 7 March 2016 ITALIAN POP VALERIO ADAMI / FRANCO ANGELI / MARIO CEROLI / TANO FESTA / GIOSETTA FIORONI / MIMMO ROTELLA / MARIO SCHIFANO / CESARE TACCHI 22 APRIL – 18 JUNE 2016 21 APRIL (10:00 – 11:30 am) Breakfast and conference on Italian Pop Art (6:00 – 8:00 pm) Private View For the second group show in its Mayfair gallery, Tornabuoni Art London leaves the abstraction of Lucio Fontana and Arnaldo Pomodoro to focus on the socially engaged and figurative movement of Italian Pop Art. “We wanted to provide a counterpoint to Italian post-war abstraction and the Milanese avant-garde that we typically show at Tornabuoni Art,” says gallery director Ursula Casamonti, “and present a different side to the Italian 1960s, one driven by Rome and by the people’s relationship to Italian culture and the ‘Dolce Vita’.” The transition from abstraction to figurative Pop aesthetics becomes evident with the work of Mimmo Rotella (1918 - 2006), whose décollage practice consisted in tearing and superposing posters, and then peeling parts of each layer in order to obtain unique works of art. At first completely abstract, Rotella later became interested in using the vernacular of popular films and advertising, exploiting the imagery of their posters; making him one of precursors of Pop Art in Italy. The Italian Pop Art movement only became formalised in the early sixties, in Rome, with the founding of the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo, by Mario Schifano (1934 – 1998), Giosetta Fioroni (b. 1932), Tano Festa (1938 – 1988) and Franco Angeli (1935 -1988). -

Sarah Wilson the Visual World of French Theory the Visual World of French Theory

Sarah Wilson The Visual World of French Theory The Visual World of French Theory Sarah Wilson Figurations The Visual World of French Theory Sarah Wilson Figurations Preface and acknowledgements Introduction: Witnesses of the Future, Painters of their times Interlude: !e Datcha. Painting as manifesto Chapter 1 From Sartre to Althusser: Lapoujade, Cremonini and the turn to antihumanism Chapter 2 Pierre Bourdieu, Bernard Rancillac: ‘!e Image of the Image’ Chapter 3 Louis Althusser, Lucio Fanti: the USSR as phantom Chapter 4 Deleuze, Foucault, Guattari. Periodisations: Gérard Fromanger Chapter 5 Lyotard / Monory: Postmodern Romantics © Sarah Wilson, 2009 Chapter 6 Derrida / Adami: !e Truth in painting? ISBN 92-00986433-009 Conclusion: In Beaubourg, 1977 / 2007 Notes Yale University Press, New Haven & London List of illustrations Design: Adrien Sina Selected bibliography Preface and acknowledgements 9 Preface and acknowledgements Res severa verum gaudium. Valerio Adami inscribed these words by Seneca on the cover of the album- catalogue Derrière le miroir, which he created with Jacques Derrida in 1975. !is book is the fruit of much joy; it was challenging – and has evolved over more than a decade. My copy of Lyotard’s L’Assassinat de la peinture – Monory dates to 1985, when I visited his exhibition ‘Les Immatériaux’ at the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris – an institution to which I owe so much. In June 1994, I had the privilege of hosting Jacques Derrida at the Courtauld Institute for his lecture at the conference ‘Memory: the Question of Archives’, -

DESIRE, ABSENCE and ART in DELEUZE and LYOTARD Kiff Bamford

PARRHESIA NUMBER 16 • 2013 • 48-60 DESIRE, ABSENCE AND ART IN DELEUZE AND LYOTARD Kiff Bamford In an undated letter, Giles Deleuze writes the following to Jean-François Lyotard: One thing continues to surprise me, the more it happens that we have shared or close thoughts, the more it happens that an irritating difference comes into sight which even I don’t succeed in locating. It is like our relationship: the more I love you, the less I am able to come to grasp it, but what is it?1\ There is a proximity between the work of these two thinkers that remains little considered, it is one that also hides a subtle, but significantly different attitude to desire. The proliferation of interest in Deleuze, particularly since his death, is accompanied by new considerations of desire which echo Lyotard’s libidinal writings very strongly—Elizabeth Grosz’s 2008 Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth is one example.2 Because of the close proximity of Lyotard and Deleuze, it is rewarding to carefully consider the differences among their many similarities (and here I am consciously making no distinction between those writings authored singly by Deleuze and those written collaboratively with Guattari). The manner in which both Lyotard and Deleuze write on art might be described as writing with art and artists rather than about them, insomuch as they give prominence to the ideas, statements and working methods described, and privilege the role of the artist as enacting a different type of thought.3 In Anti-Oedipus this attitude is clear: “the artist presents paranoiac machines, miraculating-machines, and celibate machines […] the work of art is itself a desiring-machine.”4 It is not that they write in two genres: art criticism and philosophy, but that their writings cross the circumscribed boundaries of these genres to ask questions of each. -

Bearing Witness in Jean-François Lyotard and Pseudo-Dionysius Mélanie V

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 2009 Expressing the Inexpressible: Bearing Witness in Jean-François Lyotard and Pseudo-Dionysius Mélanie V. Walton Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Walton, M. (2009). Expressing the Inexpressible: Bearing Witness in Jean-François Lyotard and Pseudo-Dionysius (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/1332 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EXPRESSING THE INEXPRESSIBLE: BEARING WITNESS IN JEAN-FRANÇOIS LYOTARD AND PSEUDO-DIONYSIUS A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Mélanie Victoria Walton December 2009 Copyright by Mélanie Victoria Walton 2009 EXPRESSING THE INEXPRESSIBLE: BEARING WITNESS IN JEAN-FRANÇOIS LYOTARD AND PSEUDO-DIONYSIUS By Mélanie Victoria Walton Approved July 24, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Dr. Lanei Rodemeyer, Ph.D. Dr. Thérèse Bonin, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Philosophy Associate Professor of Philosophy (Committee Chair) (Committee Member) ________________________________ Dr. Bettina Bergo, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Philosophy (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Dean Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dr. James Swindal, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty Graduate School of Chair, Department of Philosophy Liberal Arts Associate Professor of Philosophy iii ABSTRACT EXPRESSING THE INEXPRESSIBLE: BEARING WITNESS IN JEAN-FRANÇOIS LYOTARD AND PSEUDO-DIONYSIUS By Mélanie Victoria Walton December 2009 Dissertation supervised by Dr. -

International Art Exhibitions 2017.01

International 01 Art Exhibitions 2017 International 07.01.2017 > 12.03.2017 Art Exhibitions 2017 Philippe Cognée Crowds Galerie Daniel Templon Templon Galerie Daniel Opposite page Foule sous le soleil 2014, Wax painting on canvas 200 x 200 cm Photo : B.Huet-Tutti 1 Crowd (fusion 1) 2016, Wax painting on canvas 150 x 150 cm 2 Solar Crowd 2016, Wax painting on canvas 150 x 150 cm 3 1 Tower of Babel 2 2016, Wax painting on canvas French artist Philippe Cognée returns 175 x 153 cm to Paris and Galerie Templon for the first 4 time in four years with an exhibition Cellular Tower 2 devoted to his new series of paintings of 2016, Wax painting on canvas crowds. With these works, he continues 150 x 125 cm Paris to explore the individual and the collective, the visible and invisible, the place of the real and the place of art. Figures emerge then dissolve into compact, hazy throngs within composi- tions that at first sight appear abstract. 2 Faced with such extreme pictorial Philippe Cognée was born in 1957 and density, one can no longer distinguish studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in the image as figure from the material: Nantes, where he lives and works. One ‘That which is enclosed within this layer of the leading artists of his generation, of paint, within the crowd itself, is the a Villa Médicis prize winner in 1990 and individual.’ nominee for the 2004 Marcel Duchamp Prize, he taught at the Ecole Nationale Cognée’s blurred crowds are redolent of Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Paris until visions provided by new technologies 2015. -

Cinema Lyotard: an Introduction Jean-Michel Durafour

Cinema Lyotard: An Introduction Jean-Michel Durafour To cite this version: Jean-Michel Durafour. Cinema Lyotard: An Introduction. Graham Jones and Ashley Woodward (ed.), Acinemas. Lyotard’s Philosophy of Film, Edinburgh Press University, 2017. hal-01690225 HAL Id: hal-01690225 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01690225 Submitted on 10 Apr 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cinema Lyotard: An Introduction Jean-Michel Durafour et us dispel a persistent injustice. For reasons I will come back to later, it has Ltaken several decades for the name of Jean-François Lyotard to be able to appear, without a feeling of arbitrary unfairness or of audacious anomaly, along- side those of Gilles Deleuze, André Bazin or Serge Daney in a dossier dedicated to French cinema theory (as much as Lyotard detested this word ‘theory’, which reeks of monotheism and accounting. .).1 Looking a little more closely at the facts, which are all equally as stubborn as the theoreticians, we fi nd it hard to understand how such an ostracism – there is no other word for it – has been able to impose itself in the discourse on cinema, despite the fact (we will see this later also) that numerous theoreticians, sometimes those very ones who keep obstinately quiet about it, have openly stolen Lyotard’s whole box of method- ological and operative tools (the fi gural), with more or less good fortune.