Truth-Making: What It Is Not and What It Could Be (Appeared In: Monnoyer J.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relative Interpretations and Substitutional Definitions of Logical

Relative Interpretations and Substitutional Definitions of Logical Truth and Consequence MIRKO ENGLER Abstract: This paper proposes substitutional definitions of logical truth and consequence in terms of relative interpretations that are extensionally equivalent to the model-theoretic definitions for any relational first-order language. Our philosophical motivation to consider substitutional definitions is based on the hope to simplify the meta-theory of logical consequence. We discuss to what extent our definitions can contribute to that. Keywords: substitutional definitions of logical consequence, Quine, meta- theory of logical consequence 1 Introduction This paper investigates the applicability of relative interpretations in a substi- tutional account of logical truth and consequence. We introduce definitions of logical truth and consequence in terms of relative interpretations and demonstrate that they are extensionally equivalent to the model-theoretic definitions as developed in (Tarski & Vaught, 1956) for any first-order lan- guage (including equality). The benefit of such a definition is that it could be given in a meta-theoretic framework that only requires arithmetic as ax- iomatized by PA. Furthermore, we investigate how intensional constraints on logical truth and consequence force us to extend our framework to an arithmetical meta-theory that itself interprets set-theory. We will argue that such an arithmetical framework still might be in favor over a set-theoretical one. The basic idea behind our definition is both to generate and evaluate substitution instances of a sentence ' by relative interpretations. A relative interpretation rests on a function f that translates all formulae ' of a language L into formulae f(') of a language L0 by mapping the primitive predicates 0 P of ' to formulae P of L while preserving the logical structure of ' 1 Mirko Engler and relativizing its quantifiers by an L0-definable formula. -

The Substitutional Analysis of Logical Consequence

THE SUBSTITUTIONAL ANALYSIS OF LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE Volker Halbach∗ dra version ⋅ please don’t quote ónd June óþÕä Consequentia ‘formalis’ vocatur quae in omnibus terminis valet retenta forma consimili. Vel si vis expresse loqui de vi sermonis, consequentia formalis est cui omnis propositio similis in forma quae formaretur esset bona consequentia [...] Iohannes Buridanus, Tractatus de Consequentiis (Hubien ÕÉßä, .ì, p.óóf) Zf«±§Zh± A substitutional account of logical truth and consequence is developed and defended. Roughly, a substitution instance of a sentence is dened to be the result of uniformly substituting nonlogical expressions in the sentence with expressions of the same grammatical category. In particular atomic formulae can be replaced with any formulae containing. e denition of logical truth is then as follows: A sentence is logically true i all its substitution instances are always satised. Logical consequence is dened analogously. e substitutional denition of validity is put forward as a conceptual analysis of logical validity at least for suciently rich rst-order settings. In Kreisel’s squeezing argument the formal notion of substitutional validity naturally slots in to the place of informal intuitive validity. ∗I am grateful to Beau Mount, Albert Visser, and Timothy Williamson for discussions about the themes of this paper. Õ §Z êZo±í At the origin of logic is the observation that arguments sharing certain forms never have true premisses and a false conclusion. Similarly, all sentences of certain forms are always true. Arguments and sentences of this kind are for- mally valid. From the outset logicians have been concerned with the study and systematization of these arguments, sentences and their forms. -

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935

The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu Richard Zach Calixto Badesa The Development of Mathematical Logic from Russell to Tarski: 1900–1935 Paolo Mancosu (University of California, Berkeley) Richard Zach (University of Calgary) Calixto Badesa (Universitat de Barcelona) Final Draft—May 2004 To appear in: Leila Haaparanta, ed., The Development of Modern Logic. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004 Contents Contents i Introduction 1 1 Itinerary I: Metatheoretical Properties of Axiomatic Systems 3 1.1 Introduction . 3 1.2 Peano’s school on the logical structure of theories . 4 1.3 Hilbert on axiomatization . 8 1.4 Completeness and categoricity in the work of Veblen and Huntington . 10 1.5 Truth in a structure . 12 2 Itinerary II: Bertrand Russell’s Mathematical Logic 15 2.1 From the Paris congress to the Principles of Mathematics 1900–1903 . 15 2.2 Russell and Poincar´e on predicativity . 19 2.3 On Denoting . 21 2.4 Russell’s ramified type theory . 22 2.5 The logic of Principia ......................... 25 2.6 Further developments . 26 3 Itinerary III: Zermelo’s Axiomatization of Set Theory and Re- lated Foundational Issues 29 3.1 The debate on the axiom of choice . 29 3.2 Zermelo’s axiomatization of set theory . 32 3.3 The discussion on the notion of “definit” . 35 3.4 Metatheoretical studies of Zermelo’s axiomatization . 38 4 Itinerary IV: The Theory of Relatives and Lowenheim’s¨ Theorem 41 4.1 Theory of relatives and model theory . 41 4.2 The logic of relatives . -

12 Propositional Logic

CHAPTER 12 ✦ ✦ ✦ ✦ Propositional Logic In this chapter, we introduce propositional logic, an algebra whose original purpose, dating back to Aristotle, was to model reasoning. In more recent times, this algebra, like many algebras, has proved useful as a design tool. For example, Chapter 13 shows how propositional logic can be used in computer circuit design. A third use of logic is as a data model for programming languages and systems, such as the language Prolog. Many systems for reasoning by computer, including theorem provers, program verifiers, and applications in the field of artificial intelligence, have been implemented in logic-based programming languages. These languages generally use “predicate logic,” a more powerful form of logic that extends the capabilities of propositional logic. We shall meet predicate logic in Chapter 14. ✦ ✦ ✦ ✦ 12.1 What This Chapter Is About Section 12.2 gives an intuitive explanation of what propositional logic is, and why it is useful. The next section, 12,3, introduces an algebra for logical expressions with Boolean-valued operands and with logical operators such as AND, OR, and NOT that Boolean algebra operate on Boolean (true/false) values. This algebra is often called Boolean algebra after George Boole, the logician who first framed logic as an algebra. We then learn the following ideas. ✦ Truth tables are a useful way to represent the meaning of an expression in logic (Section 12.4). ✦ We can convert a truth table to a logical expression for the same logical function (Section 12.5). ✦ The Karnaugh map is a useful tabular technique for simplifying logical expres- sions (Section 12.6). -

Logical Consequence: a Defense of Tarski*

GREG RAY LOGICAL CONSEQUENCE: A DEFENSE OF TARSKI* ABSTRACT. In his classic 1936 essay “On the Concept of Logical Consequence”, Alfred Tarski used the notion of XU~@~ZC~~NIto give a semantic characterization of the logical properties. Tarski is generally credited with introducing the model-theoretic chamcteriza- tion of the logical properties familiar to us today. However, in his hook, The &ncel>f of Lugid Consequence, Etchemendy argues that Tarski’s account is inadequate for quite a number of reasons, and is actually incompatible with the standard mod&theoretic account. Many of his criticisms are meant to apply to the model-theoretic account as well. In this paper, I discuss the following four critical charges that Etchemendy makes against Tarski and his account of the logical properties: (1) (a) Tarski’s account of logical consequence diverges from the standard model-theoretic account at points where the latter account gets it right. (b) Tarski’s account cannot be brought into line with the model-thcorctic account, because the two are fundamentally incompatible. (2) There are simple countcrcxamples (enumerated by Etchemcndy) which show that Tarski’s account is wrong. (3) Tarski committed a modal faIlacy when arguing that his account captures our pre-theoretical concept of logical consequence, and so obscured an essential weakness of the account. (4) Tarski’s account depends on there being a distinction between the “log- ical terms” and the “non-logical terms” of a language, but (according to Etchemendy) there are very simple (even first-order) languages for which no such distinction can be made. Etchemcndy’s critique raises historica and philosophical questions about important foun- dational work. -

Presupposition: a Semantic Or Pragmatic Phenomenon?

Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume. 8 Number. 3 September, 2017 Pp. 46 -59 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol8no3.4 Presupposition: A Semantic or Pragmatic Phenomenon? Mostafa OUALIF Department of English Studies Faculty of Letters and Humanities Ben M’sik, Casablanca Hassan II University, Casablanca, Morocco Abstract There has been debate among linguists with regards to the semantic view and the pragmatic view of presupposition. Some scholars believe that presupposition is purely semantic and others believe that it is purely pragmatic. The present paper contributes to the ongoing debate and exposes the different ways presupposition was approached by linguists. The paper also tries to attend to (i) what semantics is and what pragmatics is in a unified theory of meaning and (ii) the possibility to outline a semantic account of presupposition without having recourse to pragmatics and vice versa. The paper advocates Gazdar’s analysis, a pragmatic analysis, as the safest grounds on which a working grammar of presupposition could be outlined. It shows how semantic accounts are inadequate to deal with the projection problem. Finally, the paper states explicitly that the increasingly puzzling theoretical status of presupposition seems to confirm the philosophical contention that not any fact can be translated into words. Key words: entailment, pragmatics, presupposition, projection problem, semantic theory Cite as: OUALIF, M. (2017). Presupposition: A Semantic or Pragmatic Phenomenon? Arab World English Journal, 8 (3). DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol8no3.4 46 Arab World English Journal (AWEJ) Volume 8. Number. 3 September 2017 Presupposition: A Semantic or Pragmatic Phenomenon? OUALIF I. -

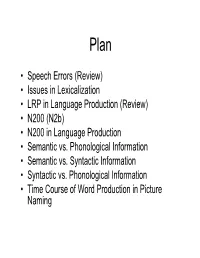

• Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic Vs

Plan • Speech Errors (Review) • Issues in Lexicalization • LRP in Language Production (Review) • N200 (N2b) • N200 in Language Production • Semantic vs. Phonological Information • Semantic vs. Syntactic Information • Syntactic vs. Phonological Information • Time Course of Word Production in Picture Naming Eech Sperrors • What can we learn from these things? • Anticipation Errors – a reading list Æ a leading list • Exchange Errors – fill the pool Æ fool the pill • Phonological, lexical, syntactic • Speech is planned in advance – Distance of exchange, anticipation errors suggestive of how far in advance we “plan” Word Substitutions & Word Blends • Semantic Substitutions • Lexicon is organized – That’s a horse of another color semantically AND Æ …a horse of another race phonologically • Phonological Substitutions • Word selection must happen – White Anglo-Saxon Protestant after the grammatical class of Æ …prostitute the target has been • Semantic Blends determined – Edited/annotated Æ editated – Nouns substitute for nouns; verbs for verbs • Phonological Blends – Substitutions don’t result in – Gin and tonic Æ gin and topic ungrammatical sentences • Double Blends – Arrested and prosecuted Æ arrested and persecuted Word Stem & Affix Morphemes •A New Yorker Æ A New Yorkan (American) • Seem to occur prior to lexical insertion • Morphological rules of word formation engaged during speech production Stranding Errors • Nouns & Verbs exchange, but inflectional and derivational morphemes rarely do – Rather, they are stranded • I don’t know that I’d -

Substitution and Propositional Proof Complexity

Substitution and Propositional Proof Complexity Sam Buss Abstract We discuss substitution rules that allow the substitution of formulas for formula variables. A substitution rule was first introduced by Frege. More recently, substitution is studied in the setting of propositional logic. We state theorems of Urquhart’s giving lower bounds on the number of steps in the substitution Frege system for propositional logic. We give the first superlinear lower bounds on the number of symbols in substitution Frege and multi-substitution Frege proofs. “The length of a proof ought not to be measured by the yard. It is easy to make a proof look short on paper by skipping over many links in the chain of inference and merely indicating large parts of it. Generally people are satisfied if every step in the proof is evidently correct, and this is permissable if one merely wishes to be persuaded that the proposition to be proved is true. But if it is a matter of gaining an insight into the nature of this ‘being evident’, this procedure does not suffice; we must put down all the intermediate steps, that the full light of consciousness may fall upon them.” [G. Frege, Grundgesetze, 1893; translation by M. Furth] 1 Introduction The present article concentrates on the substitution rule allowing the substitution of formulas for formula variables.1 The substitution rule has long pedigree as it was a rule of inference in Frege’s Begriffsschrift [9] and Grundgesetze [10], which contained the first in-depth formalization of logical foundations for mathematics. Since then, substitution has become much less important for the foundations of Sam Buss Department of Mathematics, University of California, San Diego, e-mail: [email protected], Supported in part by Simons Foundation grant 578919. -

The History of Logic

c Peter King & Stewart Shapiro, The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (OUP 1995), 496–500. THE HISTORY OF LOGIC Aristotle was the first thinker to devise a logical system. He drew upon the emphasis on universal definition found in Socrates, the use of reductio ad absurdum in Zeno of Elea, claims about propositional structure and nega- tion in Parmenides and Plato, and the body of argumentative techniques found in legal reasoning and geometrical proof. Yet the theory presented in Aristotle’s five treatises known as the Organon—the Categories, the De interpretatione, the Prior Analytics, the Posterior Analytics, and the Sophistical Refutations—goes far beyond any of these. Aristotle holds that a proposition is a complex involving two terms, a subject and a predicate, each of which is represented grammatically with a noun. The logical form of a proposition is determined by its quantity (uni- versal or particular) and by its quality (affirmative or negative). Aristotle investigates the relation between two propositions containing the same terms in his theories of opposition and conversion. The former describes relations of contradictoriness and contrariety, the latter equipollences and entailments. The analysis of logical form, opposition, and conversion are combined in syllogistic, Aristotle’s greatest invention in logic. A syllogism consists of three propositions. The first two, the premisses, share exactly one term, and they logically entail the third proposition, the conclusion, which contains the two non-shared terms of the premisses. The term common to the two premisses may occur as subject in one and predicate in the other (called the ‘first figure’), predicate in both (‘second figure’), or subject in both (‘third figure’). -

Review of Gregory Landini, Russell's Hidden Substitutional Theory

eiews SUBSTITUTION AND THE THEORY OF TYPES G S Philosophy / U. of Manchester Oxford Road, Manchester, .., ..@.. Gregory Landini. Russell’s Hidden Substitutional Theory. Oxford and New York: Oxford U.P., . Pp. xi, .£.; .. hen, in , Russell communicated to Frege the famous paradox of the Wclass of all classes which are not members of themselves, Frege im- mediately located the source of the contradiction in his generous attitude towards the existence of classes. The discovery of Russell’s paradox exposed the error in Frege’s reasoning, but it was left to Whitehead and Russell to reformu- late the logicist programme without the assumption of classes. Yet the “no- classes” theory that eventually emerged in Principia Mathematica, though admired by many, has rarely been accepted without significant alterations. Almost without exception, these calls for alteration of the system have been induced by distaste for the theory of types in Principia. Much of the dissatisfaction that philosophers and logicians have felt about type-theory hinged on Whitehead and Russell’s decision to supplement the hierarchy of types (as applied to propositional functions) with a hierarchy of orders restricting the range of quantifiers so as to obtain the ramified theory of types. This ramified system was roundly criticized, predominantly because it necessitated the axiom of reducibility—famously denounced as having “no place in mathematics” by Frank Ramsey, who maintained that “anything which cannot be proved without it cannot be regarded as proved at all”. Russell himself, who had admitted that the axiom was not “self-evident” in the first edition of Principia (PM, : ), explored the possibility of removing the axiom in the second edition. -

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4

Logic and Proof Release 3.18.4 Jeremy Avigad, Robert Y. Lewis, and Floris van Doorn Sep 10, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Mathematical Proof ............................................ 1 1.2 Symbolic Logic .............................................. 2 1.3 Interactive Theorem Proving ....................................... 4 1.4 The Semantic Point of View ....................................... 5 1.5 Goals Summarized ............................................ 6 1.6 About this Textbook ........................................... 6 2 Propositional Logic 7 2.1 A Puzzle ................................................. 7 2.2 A Solution ................................................ 7 2.3 Rules of Inference ............................................ 8 2.4 The Language of Propositional Logic ................................... 15 2.5 Exercises ................................................. 16 3 Natural Deduction for Propositional Logic 17 3.1 Derivations in Natural Deduction ..................................... 17 3.2 Examples ................................................. 19 3.3 Forward and Backward Reasoning .................................... 20 3.4 Reasoning by Cases ............................................ 22 3.5 Some Logical Identities .......................................... 23 3.6 Exercises ................................................. 24 4 Propositional Logic in Lean 25 4.1 Expressions for Propositions and Proofs ................................. 25 4.2 More commands ............................................ -

Warren Goldfarb, Notes on Metamathematics

Notes on Metamathematics Warren Goldfarb W.B. Pearson Professor of Modern Mathematics and Mathematical Logic Department of Philosophy Harvard University DRAFT: January 1, 2018 In Memory of Burton Dreben (1927{1999), whose spirited teaching on G¨odeliantopics provided the original inspiration for these Notes. Contents 1 Axiomatics 1 1.1 Formal languages . 1 1.2 Axioms and rules of inference . 5 1.3 Natural numbers: the successor function . 9 1.4 General notions . 13 1.5 Peano Arithmetic. 15 1.6 Basic laws of arithmetic . 18 2 G¨odel'sProof 23 2.1 G¨odelnumbering . 23 2.2 Primitive recursive functions and relations . 25 2.3 Arithmetization of syntax . 30 2.4 Numeralwise representability . 35 2.5 Proof of incompleteness . 37 2.6 `I am not derivable' . 40 3 Formalized Metamathematics 43 3.1 The Fixed Point Lemma . 43 3.2 G¨odel'sSecond Incompleteness Theorem . 47 3.3 The First Incompleteness Theorem Sharpened . 52 3.4 L¨ob'sTheorem . 55 4 Formalizing Primitive Recursion 59 4.1 ∆0,Σ1, and Π1 formulas . 59 4.2 Σ1-completeness and Σ1-soundness . 61 4.3 Proof of Representability . 63 3 5 Formalized Semantics 69 5.1 Tarski's Theorem . 69 5.2 Defining truth for LPA .......................... 72 5.3 Uses of the truth-definition . 74 5.4 Second-order Arithmetic . 76 5.5 Partial truth predicates . 79 5.6 Truth for other languages . 81 6 Computability 85 6.1 Computability . 85 6.2 Recursive and partial recursive functions . 87 6.3 The Normal Form Theorem and the Halting Problem . 91 6.4 Turing Machines .