Temporal Expression in Wichi Nominals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core Folkbiological Concepts: New Evidence from Wichí Children and Adults

Journal of Cognition and Culture 12 (2012) 339–358 brill.com/jocc Core Folkbiological Concepts: New Evidence from Wichí Children and Adults Andrea S. Tavernaa,*, Sandra R. Waxmanb, Douglas L. Medinb and Olga A. Peraltac a Instituto de Investigaciones Lingüísticas (INIL), Facultad de Humanidades, Universidad Nacional de Formosa (UNaF), Av. Gutnisky 3200, 3600 Formosa, Argentina b Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Swift Hall 102, 2029 Sheridan Road, Evanston, IL 60208-2710, USA c Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (National Research Council), Instituto Rosario de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Educación, IRICE, 27 de Febrero 210bis, 2000 Rosario, Argentina * Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract We examine two core folk-biological concepts (e.g., animate, living thing, where small capital letters denote concepts; quotation marks denote their names; italics denote language- specific names) in adults and children from the Wichí community, an indigenous group of Amerindians living in the Chaco forest in north Argentina. We provide an overview of the Wichí community, describing in brief their interaction with objects and events in the natural world, and the naming systems they use to describe key folkbiological concepts. We then report the results of two behavioral studies, each designed to deepen our understanding of the acquisition of the fundamental folkbiological concepts animate and living thing in Wichí adults and children. These results converge well with evidence from other communities.Wichí children and adults appreciate these fundamental concepts; both are strongly aligned with the Wichí community-wide belief systems. This work underscores the importance of considering cultural and linguistic factors in studying the acquisition of fundamental concepts about the biological world. -

The Renewal of Gran Chaco Studies Edgardo Krebs

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarlyCommons@Penn History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 38 Article 4 Issue 1 June 2011 1-1-2011 The Renewal of Gran Chaco Studies Edgardo Krebs José Braunstein This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol38/iss1/4 For more information, please contact [email protected]. History of Anthropology Newsletter 38.1 (June 2011) / 9 The Renewal of Gran Chaco Studies Edgardo Krebs1 and Jose Braunstein2 Interest in the Gran Chaco among social scientists during most of the 20th century has not been high. In comparison to the Amazon, or the Andes, this enormous territory, over 500,000 square miles, has inspired a modest output of scholarly studies, its very existence as a distinct and important ecological and ethnographic area seemingly lost in the shadows of the other two neighboring giants. Its vast dry plains—“a park land with patches of hardwoods intermingled with grasslands”3—is the second largest biome in South America, after the Amazon. It is shared by four countries, Paraguay, Bolivia, Brazil and Argentina; and in all of them it represents pockets of wilderness coming under the increasing stress of demographic expansion and economic exploitation. In all of these countries the Chaco is also an ethnographic frontier, still open after centuries of contact, and still the refuge of last resort of a few elusive Indian groups. The comparative neglect of the Gran Chaco as an area of interest for anthropologists is also remarkable considering that the Provincia Paraguaria of the Jesuit order yielded a number of Chaco ethnographies extraordinary in their narrative complexity and analytical edge, and that, closer in time to us, one of the pioneers of modern fieldwork, Guido Boggiani (1861–1902), died tragically in the Chaco, during the course of an expedition. -

Wichí Folkbiological Concepts 1 RUNNING HEAD: Wichí

Wichí folkbiological concepts RUNNING HEAD: Wichí folkbiological concepts Taverna, A., Waxman, S., Medin, D., Peralta, O. (2012). Core-folkbiological concepts: New evidence from Wichí children and adults. Journal of Cognition and Culture. 12 (2012) 339– 358. Core folkbiological concepts: New evidence from Wichí children and adults Andrea S. Taverna Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (National Research Council) Formosa, Argentina Sandra R.Waxman and Douglas L. Medin Northwestern University Olga A. Peralta Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (National Research Council) Rosario, Argentina Author Note: This research was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the National Research Council of Argentina to the first author, by the National Science Foundation under Grants BCS 0745594 and DRL 0815020, to the second and third authors, and by Grant PIP 1099 from the National Research Council and Grant PICT 01754 from the National Agency of Scientific Promotion to the fourth author. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Andrea Taverna, Instituto de Investigaciones Lingüísticas (INIL), Facultad de Humanidades, Universidad 1 Wichí folkbiological concepts Nacional de Formosa (UNaF) Av. Gutnisky 3200, C.P. 3600, Formosa, Argentina. Phone: 54 370 4452473. E-mail: [email protected] Core folkbiological concepts: New evidence from Wichí children and adults Abstract 1 We examine two core folk-biological concepts (e.g., ANIMATE, LIVING THING ) in adults and children from the Wichí community, an indigenous group of Amerindians living in the Chaco forest in north Argentina. We provide an overview of the Wichí community, describing in brief their interaction with objects and events in the natural world, and the naming systems they use to describe key folkbiological concepts. -

The Changing Role of Chaguar Textiles in the Lives of the Wichí, an Indigenous People of Argentina

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2016 The hC anging Role of Chaguar Textiles in the Lives of the Wichí, an Indigenous People of Argentina Rachel Green [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Green, Rachel, "The hC anging Role of Chaguar Textiles in the Lives of the Wichí, an Indigenous People of Argentina" (2016). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 951. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/951 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Crosscurrents: Land, Labor, and the Port. Textile Society of America’s 15th Biennial Symposium. Savannah, GA, October 19-23, 2016. 126 The Changing Role of Chaguar Textiles in the Lives of the Wichí, an Indigenous People of Argentina Rachel Green [email protected] Beating, spinning, and sewing fiber, a woman works to perpetuate her culture a thread and stitch at a time. While her hands work expertly and she talks casually, Carolina is crocheting a hat from a fiber called chaguar to be worn under a motorcycle helmet. She learned to crochet five years ago from a nonindigenous woman whose house she was paid to clean. -

Reasoning About Folkbiological Concepts in Wichi Children and Adults

Early Education and Development ISSN: 1040-9289 (Print) 1556-6935 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/heed20 “Inhabitants of the Earth”: Reasoning About Folkbiological Concepts in Wichi Children and Adults Andrea S. Taverna, Douglas L. Medin & Sandra R. Waxman To cite this article: Andrea S. Taverna, Douglas L. Medin & Sandra R. Waxman (2016): “Inhabitants of the Earth”: Reasoning About Folkbiological Concepts in Wichi Children and Adults, Early Education and Development, DOI: 10.1080/10409289.2016.1168228 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1168228 Published online: 28 Apr 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 2 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=heed20 Download by: [Andrea Taverna] Date: 02 May 2016, At: 11:16 EARLY EDUCATION AND DEVELOPMENT http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1168228 “Inhabitants of the Earth”: Reasoning About Folkbiological Concepts in Wichi Children and Adults Andrea S. Tavernaa, Douglas L. Medinb, and Sandra R. Waxmanb aLinguistic Research Institute, National Research Council, Formosa, Argentina; bDepartment of Psychology, Northwestern University ABSTRACT Across the world, people form folkbiological categories to capture their commonsense organization of the natural world. Structured in accordance with universal principles, folkbiological categories are also shaped by experience. Here we provide new evidence from the Wichi—an understu- died indigenous community who live in the Chaco rainforest and speak their heritage language. A total of 44 Wichi (6- to 8-year-olds, 9- to 12-year- olds, adults) participated in an induction task designed to identify how broadly they attribute an invisible biological property (e.g., an internal organ) from 1 individual (either a human, nonhuman animal, or plant) to other humans, nonhuman animals, plants, natural kinds, and artifacts. -

Wild Food Plants Used by the Indigenous Peoples of the South American Gran Chaco: a General Synopsis and Intercultural Comparison Gustavo F

Journal of Applied Botany and Food Quality 83, 90 - 101 (2009) Center of Pharmacological & Botanical Studies (CEFYBO) – National Council of Scientific & Technological Research (CONICET), Argentinia Wild food plants used by the indigenous peoples of the South American Gran Chaco: A general synopsis and intercultural comparison Gustavo F. Scarpa (Received November 13, 2009) Summary The Gran Chaco is the most extensive wooded region in South America after the Amazon Rain Forest, and is also a pole of cultural diversity. This study summarises and updates a total of 573 ethnobotanical data on the use of wild food plants by 10 indigenous groups of the Gran Chaco, as published in various bibliographical sources. In addition, estimates are given as to the levels of endemicity of those species, and intercultural comparative analyses of the plants used are made. A total of 179 native vegetable taxa are used as food of which 69 are endemic to, or characteristic of, this biogeographical region. In all, almost half these edible species belong to the Cactaceae, Apocynaceae, Fabaceae and Solanaceae botanical families, and the most commonly used genera are Prosopis, Opuntia, Solanum, Capparis, Morrenia and Passiflora. The average number of food taxa used per ethnic group is around 60 species (SD = 12). The Eastern Tobas, Wichi, Chorote and Maká consume the greatest diversity of plants. Two groups of indigenous peoples can be distinguished according to their relative degree of edible plants species shared among them be more or less than 50 % of all species used. A more detailed look reveals a correlation between the uses of food plants and the location of the various ethnic groups along the regional principal rainfall gradient. -

Wichí-Lhuku’Tas

revista ANTHROPOLÓGICAS Ano 21, 28(1):279-293, 2017 ENSAIO BIBLIOGRÁFICO A Look at the Sky of the Wichi Mauro Mariania Cecilia Paula Gómezb Sixto Giménez Benítezc The Wichi and the perception of the sky The Wichi are known as a group of ‘hunter-gatherers’ who belong to the Mataco-Maká language family together with other ethnic groups such as the Chorote, the Maká and the Nivaclé. At present, they num- ber around 40,000 and are scattered over approximately 100,000 km (Alvarsson 1983, Braunstein 1993). Several asterisms may be traced among Wichi groups and some of them can be named based on the existing bibliography. Thanks to earlier anthropological work (Braunstein 1976 and 1993) it can be stated that, despite their global denomination and lan- guage affinities, the Wichi are not a people with identical characteris- a Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Universidad Nacional de la Plata (Argentina). Email: [email protected]. b Investigadora del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. Universidad de Buenos Aires (Ar- gentina). Centro de Investigaciones Históricas y Antropológicas (CIHA). Email: [email protected]. c Facultad de Ciencias Astronómicas y Geofísicas, Universidad Nacional de la Plata (Argentina). Email: [email protected]. ANTHROPOLÓGICAS 28(1):279-293, 2017 tics. These groups make up an ethnic ‘chain’ with other communities that exhibit differences in language and traditions. For the first time, a compilation of this kind is made. We know that, like other indigenous peoples with whom we have worked, the Wichi have their own asterisms, their own reading of the sky, and that it has not disappeared despite their contact with the surrounding society. -

Loanwords in Wichí, a Mataco-Mataguayan Language of Argentina Alejandra Vidal Verónica Nercesian

1 Loanwords in Wichí, a Mataco-Mataguayan language of Argentina Alejandra Vidal Verónica Nercesian 1. The language and its speakers Wichí has approximately 40,000 speakers in Argentina and Bolivia. In Argentina, it is spoken in the western and central parts of the provinces of Salta and Formosa, and in the northeastern part of the province of Chaco. In Bolivia, it is spoken in Tarija County. The data for this study are based on fieldwork on the Bermejo dialect, which has approximately 3,000 speakers in the province of Formosa, Argentina. All of the communities in Formosa are organized as Civil Associations with legal status. In addition to hunting and gathering activities, they have also developed textile weaving, pottery, and, to a lesser extent, ranching and some degree of farming. There is an ongoing tendency for these families in rural communities and their urban relatives to migrate. This has to do, among other reasons, with the search for part-time jobs, the sale of their crafts, the need for health care services, the completion of administrative procedures, and the payment of subsidies. Some of the elderly and the heads of families receive government pensions and a small group (3%) is employed by the state. An alternative name of Wichí that was current until recently is Mataco. The Wichí language belongs to the Mataco-Mataguayan family, spoken in the region known as Chaco. The other languages of the family are Maká, Chorote and Nivaklé. The Chaco region is located in the South American Lowlands and includes the great woody plain bounded on the west and southwest by the Andes and the Salado River basin, in the east by the Paraguay and Parana Rivers and in the north by the Moxos and Chiquitos Plains. -

Yuri Marder in Search of Exile

Yuri Marder In Search of Exile The city of Salta lies on a rocky plateau of northern Argentina where the vast grasslands of the Pampas have given way to the foothills of the Andes mountains. It was my first trip to this provincial city, but not my first time in Argentina. A decade before, a young man with no direction and little potential, I had spent an indolent year living in an ancient hotel in the red-light district of Buenos Aires which bordered the ornate mausoleum-filled Recoleta cemetery. Aimless and insecure I ate my breakfast of croissants and café con leche, and then would wander along the grimy main avenue, often stopping at a little shop to buy a newspaper. The shop had seen better days, it was sparsely stocked — a few rolls of film, half-filled racks of magazines, dusty toys, sooty packages of dress socks. In the front window, a few faded cans of soda sat alongside a dusty antique camera. The owner of the shop, a small grey man with a Russian accent, elderly and unfriendly, at first took little notice of me but over time began to take interest in the shy American who always greeted him with a strained smile. We would talk about politics and the weather often failing to comprehend one another through our shaky accented Spanish. One day he noticed me admiring the camera, and gave a little frown. He had been born in St. Petersburg around the time of the Bolshevik revolution. As a teenager he developed a passion for photography, and after saving up for several years, sent to Germany for a 1920 Zeiss Ikonta, a folding camera with leather bellows and small hand-ground lens; top of the line, the best he could afford. -

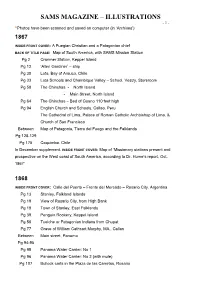

SAMS MAGAZINE – ILLUSTRATIONS - 1 - *Photos Have Been Scanned and Saved on Computer (In ‘Archives’)

SAMS MAGAZINE – ILLUSTRATIONS - 1 - *Photos have been scanned and saved on computer (in ‘Archives’) 1867 INSIDE FRONT COVER: A Fuegian Christian and a Patagonian chief BACK OF TITLE PAGE: Map of South America, with SAMS Mission Station Pg 2 Cranmer Station, Keppel Island Pg 12 ‘Allen Gardiner’ – ship Pg 30 Lota, Bay of Arauco, Chile Pg 33 Lota Schools and Chambique Valley – School, Vestry, Storeroom Pg 58 The Chinchas - North Island - Main Street, North Island Pg 64 The Chinchas – Bed of Guano 110 feet high Pg 94 English Church and Schools, Callao, Peru The Cathedral of Lima, Palace of Roman Catholic Archbishop of Lima, & Church of San Francisco Between Map of Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego and the Falklands Pg 128-129 Pg 175 Coquimbo, Chile In December supplement. INSIDE FRONT COVER: Map of ‘Missionary stations present and prospective on the West coast of South America, according to Dr. Hume’s report, Oct. 1867’ 1868 INSIDE FRONT COVER: Calle del Puerto – Frente del Mercado – Rosario City, Argentina Pg 13 Stanley, Falkland Islands Pg 19 View of Rosario City, from High Bank Pg 19 Town of Stanley, East Falklands Pg 39 Penguin Rookery, Keppel Island Pg 58 Tuelche or Patagonian Indians from Chupat Pg 77 Grave of William Cathcart Murphy, MA., Callao Between Main street, Panama Pg 94-95 Pg 95 Panama Water Carrier: No 1 Pg 96 Panama Water Carrier: No 2 (with mule) Pg 107 Bullock carts in the Plaza de las Carretas, Rosario SAMS MAGAZINE – ILLUSTRATIONS - 2 - Pg 129 Tacna, Peru – principal street Arica, Peru, landing place Pg 141 English Church, Monte Video Pg 142 Map of Uruguay, showing Salto, Paysandu, Fray Bentos, Colonia, Monte Video, Río de la Plata and Buenos Aires Pg 153 Arequipa and Mount Misti, Peru Grand Plaza, Market Place and Cathedral, Arequipa Pg 171 Indian mother and child, Peru Pg 186 Iquique, Peru, before the earthquake of 13/8/1868 Pg 189 Arica, Peru, after the earthquake of 13/08/1868 Pg 210 Mission Stations. -

Ancient Law and Indian Rights: an Historical Perspective from the Argentine Chaco

History of Anthropology Newsletter Volume 35 Issue 2 December 2008 Article 3 January 2008 Ancient Law and Indian Rights: An Historical Perspective From the Argentine Chaco Edgardo Krebs José Braunstein Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons Recommended Citation Krebs, Edgardo and Braunstein, José (2008) "Ancient Law and Indian Rights: An Historical Perspective From the Argentine Chaco," History of Anthropology Newsletter: Vol. 35 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol35/iss2/3 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/han/vol35/iss2/3 For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORY OF ANTHROPOlOGY NEWSlETTER 35.2 (DECEMBER 2008) /3 Ancient Law and Indian Rights: An Historical Perspective From the Argentine Chaco, By Edgar Krebs, NMNH, Smithsonian Institution, and Jose Braunstein, CONICET, Argentina. Sans doute les phenomenes juridiques ont-ils voyage, comme tous les autres elements de civilisation, mals d'une man/ere dlfferente : lis voyagent par sauts. --Marcel Mauss, Manuel d' Ethnographle. 2 While doing fieldwork in southern Madagascar, one of us--an E.O. Wilson book on biodiversity In hand--asked a Tatslmo farmer to give the names of the different species of chameleons in the land. Madagascar is, in the parlance of conservationists, a "biodiversity hotspot," and the place on earth with the largest number of species of chameleons. Not for the Tatsimo farmer. 3 He recognized just one archetypical chameleon. Its different shapes were attributes of the negative, shifty, social--not biological--place this creature has in the Tatsimo imagination. -

Relations with Wildlife of Wichi and Criollo People of the Dry Chaco, a Conservation Perspective

RESEARCH ARTICLE Ethnobiology and Conservation 2018, 7:11 (20 August 2018) doi:10.15451/ec2018-08-7.11-1-21 ISSN 22384782 ethnobioconservation.com Relations with wildlife of Wichi and Criollo people of the Dry Chaco, a conservation perspective Micaela Camino1,2,3,4; Sara Cortez4, Mariana Altrichter5,6; Silvia D. Matteucci2,7 ABSTRACT Indigenous Wichís and mestizos Criollos inhabit a rural, biodiversity rich, area of the Argentinean Dry Chaco. Traditionally, Wichís were nomads and their relations with wildlife were shaped by animistic and shamanic beliefs. Today, Wichís live in stable communities and practice subsistence hunting, gathering and in some cases, fishing. Criollos are mestizos, i.e. a mixture of the first Spanish settlers and different indigenous groups. They arrived during the 20th century from neighbouring Provinces. They practice extensive ranching, hunting and gathering. Our aim was to help develop effective and legitimate actions to conserve wildlife species in this region, focused on Wichís´ and Criollos´ perceptions of and relations with wildlife. We conducted semistructured interviews (N=105) in rural settlements. We found differences in both groups´ hunting techniques, drivers and perceptions on the importance of wild meat for nutrition. However, both groups have a close relation with wildlife, they use wild animals in a variety of ways, including as food resource, medicine and predictors of future events. Wichís and Criollos also relate with wildlife in a spiritual dimension, have animistic and shamanic beliefs and have unique traditional ecological knowledge. Hunters in both communities are breaking traditional hunting norms but conservation measures grounded on these norms have a higher probability of success.