Wz% Ms\ Egga Rflss Rosl I2s2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week Ending 28 May 2021

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 21 Week Ending: 28th May 2021 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including email) to arrive before the application publicity expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 21/01570/FULLN Demolition of existing Pinchbecks Car Centre, Imperial Homes Fay Eames 24.05.2021 buildings and erect 4 Abbotts Ann Service Station, Southern 19.06.2021 ABBOTTS ANN detached bungalows with Salisbury Road, Abbotts Ann parking Andover Hampshire 21/01627/TPON Yew - Prune western side by Greenhaven , 23 Hillside, Mr Michael Taylor Mr Rory Gogan YES 28.05.2021 0.5m - 1m Abbotts Ann, SP11 7DF 21.06.2021 ABBOTTS ANN 21/01576/FULLN To remove existing 14 Ferndale Road, Andover, Mr And Mrs Hood Mr Luke Benjamin 24.05.2021 conservatory and replace SP10 3HQ, 18.06.2021 ANDOVER TOWN with -

Week Ending 12Th February 2010

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 06 Week Ending: 12th February 2010 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column For the Northern Area to: For the Southern Area to: Head of Planning Head of Planning Beech Hurst Council Offices Weyhill Road Duttons Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ ROMSEY SO51 8XG In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 10/00166/FULLN Erection of two replacement 33 And 34 Andover Road, Red Mr & Mrs S Brown Jnr Mrs Lucy Miranda YES 08.02.2010 dwellings together with Post Bridge, Andover, And Mr R Brown Page ABBOTTS ANN garaging and replacement Hampshire SP11 8BU 12.03.2010 and resiting of entrance gates 10/00248/VARN Variation of condition 21 of 11 Elder Crescent, Andover, Mr David Harman Miss Sarah Barter 10.02.2010 TVN.06928 - To allow garage Hampshire, SP10 3XY 05.03.2010 ABBOTTS ANN to be used for storage room -

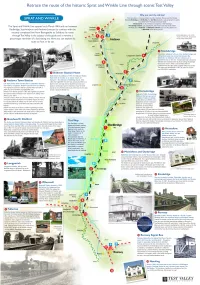

Sprat and Winkle Line Leaflet

k u . v o g . y e l l a v t s e t @ e v a e l g d t c a t n o c e s a e l P . l i c n u o C h g u o r o B y e l l a V t s e T t a t n e m p o l e v e D c i m o n o c E n i g n i k r o w n o s n i b o R e l l e h c i M y b r e h t e g o t t u p s a w l a i r e t a m e h T . n o i t a m r o f n I g n i d i v o r p r o f l l e s d n i L . D r M d n a w a h s l a W . I r M , n o t s A H . J r M , s h p a r g o t o h p g n i d i v o r p r o f y e l r e s s a C . R r M , l l e m m a G . C r M , e w o c n e l B . R r M , e n r o H . M r M , e l y o H . R r M : t e l f a e l e l k n i W d n a t a r p S e h t s d r a w o t n o i t a m r o f n i d n a s o t o h p g n i t u b i r t n o c r o f g n i w o l l o f e h t k n a h t o t e k i l d l u o w y e l l a V t s e T s t n e m e g d e l w o n k c A . -

Week Ending 22Nd May 2015

TEST VALLEY BOROUGH COUNCIL – PLANNING SERVICES _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WEEKLY LIST OF PLANNING APPLICATIONS AND NOTIFICATIONS : NO. 21 Week Ending: 22nd May 2015 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Comments on any of these matters should be forwarded IN WRITING (including fax and email) to arrive before the expiry date shown in the second to last column Head of Planning and Building Beech Hurst Weyhill Road ANDOVER SP10 3AJ In accordance with the provisions of the Local Government (Access to Information Act) 1985, any representations received may be open to public inspection. You may view applications and submit comments on-line – go to www.testvalley.gov.uk APPLICATION NO./ PROPOSAL LOCATION APPLICANT CASE OFFICER/ PREVIOUS REGISTRATION PUBLICITY APPLICA- TIONS DATE EXPIRY DATE 15/00984/ADVN Internally illuminated fascia Unit 1B , 132 Weyhill Road, Dr M Chitnis Rebecca Redford YES 20.05.2015 signage Andover, Hampshire SP10 3BE 13.06.2015 ANDOVER TOWN (HARROWAY) 15/01089/FULLN Refurbishment of pub and The George Hotel , George Mr Steve Cox Mrs Samantha YES 21.05.2015 creation of four self Yard, Andover, Hampshire Owen ANDOVER TOWN contained flats with separate SP10 1PD 19.06.2015 (ST MARYS) entrance. New bin and bike store. 15/01090/LBWN Refurbishment of pub and The George Hotel , George Mr Steve Cox Mrs Samantha YES 21.05.2015 creation of four self Yard, Andover, Hampshire Owen -

Parish Churches of the Test Valley

to know. to has everything you need you everything has The Test Valley Visitor Guide Visitor Valley Test The 01264 324320 01264 Office Tourist Andover residents alike. residents Tourist Office 01794 512987 512987 01794 Office Tourist Romsey of the Borough’s greatest assets for visitors and and visitors for assets greatest Borough’s the of villages and surrounding countryside, these are one one are these countryside, surrounding and villages ensure visitors are made welcome to any of them. of any to welcome made are visitors ensure of churches, and other historic buildings. Together with the attractive attractive the with Together buildings. historic other and churches, of date list of ALL churches and can offer contact telephone numbers, to to numbers, telephone contact offer can and churches ALL of list date with Bryan Beggs, to share the uniqueness of our beautiful collection collection beautiful our of uniqueness the share to Beggs, Bryan with be locked. The Tourist Offices in Romsey and Andover hold an up to to up an hold Andover and Romsey in Offices Tourist The locked. be This leaflet has been put together by Test Valley Borough Council Council Borough Valley Test by together put been has leaflet This church description. Where an is shown, this indicates the church may may church the indicates this shown, is an Where description. church L wide range of information to help you enjoy your stay in Test Valley. Valley. Test in stay your enjoy you help to information of range wide every day. Where restrictions apply, an is indicated at the end of the the of end the at indicated is an apply, restrictions Where day. -

Longparish Cemetery

Cemetery analysis Graves located on Cemetery extension map NOTE: Due to earlier formatting it looks like many of the dates have automatically become the first of the month Reservations Born Burial Grave Burial Grant Burial Grant Grave Reservation Notice of Certificate Fee for Application Fee for Date of death Date of Burial Surname Forenames Occupation Abode Age (calculated) Register xl cemetery map number from paperwork Number Date completed number fee In accounts Undertaker interment burial/cremation burial In accounts for memorial Stonemason memorial in accounts Inscription Notes 21/06/1905 Taylor Dorothy 86 1819 No 29/03/1932 Sawyer Susan Longparish 45 1887 513 02/04/1932 Newell Fanny Longparish 85 1847 516 04/05/1932 Smith George Longparish 36 1896 515 04/05/1932 Guyatt Jane Wherwell 76 1856 514 13/05/1932 Cockcraft Albert Red Roofs, Longparish 59 1873 517 02/06/1932 Ralph Sarah Longparish 77 1855 518 11/06/1932 Malt Eliza Forton, Longparish 77 1855 519 19 09/03/31 19 15/08/1932 Tubbs Walter Charles Owls Lodge, Longparish 59 1873 520 22/08/1932 White Dorothy Eileen Longparish 5 1927 521 01/12/1932 Brackstone Alice Longparish 67 1865 522 05/12/1932 Harmer George William Tree Tops, Wherwell 77 1855 523 16/01/1933 Alexander Jane District Villas, Longparish 50 1883 524 18/01/1933 Mason Arthur Firgrove, Longparish 37 1896 525 23/01/1933 Ball Ellen Longparish 81 1852 526 27/03/1933 Walker stillborn child of Stanley & Edith Longparish 0 1933 527 29/04/1933 Sweatman Jemima Fox Farm, Longparish 90 1843 529 5 07/10/25 6 29/04/1933 Carter Joseph -

The Middleton Estate

WELCOME TO THE MIDDLETON ESTATE Dear Angler, Welcome to the Middleton Estate! By now I hope you are settled and are relaxing with a cup of coffee. Here is a summary of the fishing and what to expect; have a lovely day. THE RIVER TEST The River Test has a total length of 40 miles and flows through the Hampshire downlands from its source near Overton, 6 miles to the west of Basingstoke, to the sea at the head of Southampton Water. The river rises in the village of Ashe, and flows west through the villages of Overton, Laverstoke, and the town of Whitchurch, before joining with the Bourne Rivulet at Testbourne and turning into a more southerly direction. It then flows through the villages of Longparish and Middleton to Wherwell and Chilbolton, where the Rivers Dever and Anton contribute to the flow. From Chilbolton the river flows through the villages of Leckford, Longstock, Stockbridge and Houghton to Mottisfont and Kimbridge, where the River Dun joins the flow. From here the village of Timsbury is passed, then through the grounds of Roke Manor before reaching the town of Romsey. On the western edge of Romsey, Sadler's Mill, an 18th Century watermill, sits astride the River Test. South of Romsey, the river flows past the country house of Broadlands, past Nursling that was once the site of a Roman bridge, and between Totton and Redbridge. Here the river is joined by the River Blackwater and soon becomes tidal, widening out into a considerable estuary that is lined on its northern bank by the container terminals and quays of the Port of Southampton. -

1891 Census Transcription Barton Stacey Parish RG12 Piece 962, Folios 18-28 (Covering 21 Pages of Census Images)

1891 Census for Barton Stacey Parish. 1 Please report errors and additional information Transcribed by Anne Harrison. Copyright Barton Stacey Parish Local History Group, 2013. to [email protected] 1891 census transcription Barton Stacey parish RG12 Piece 962, folios 18-28 (covering 21 pages of census images). HD head of household, WI wife, S son, D daughter, StepD step-daughter, BR brother, SI sister, GS/GD grandson/daughter, GF/GM grandfather/mother, FA father, MO mother, NI niece, NE nephew, AU aunt, UN uncle, SL/DL/BL/SiL/FL/ML/ son/ daughter/ brother/ sister/ father/ mother-in-law. SE servant, BO boarder, LO lodger, VI visitor, HK housekeeper. M married, S single, W widow(er). Note: we have transcribed as faithfully as possible the original writing of the enumerator. Sometimes this has been difficult and where there is any doubt we have made this clear. Note that the areas of the parish (column 2) are added from our knowledge of the parish Sch Area of parish Address Forename(s) Surname Rel'p Marital Age Occupation Employer, County of Town of birth Notes added by the Barton Stacey Parish Local History edul This was sometimes to Status in employed or birth Group e abbreviated by the HD 1891 neither [box enumerator to fit it into left blank = none of these. the alloted space. 1 Barton Stacey Manor Farm H. John P. WILTSHIRE HD M 27 Farm Bailiff employed Wilts. Chippenham 1 Sarah M. WILTSHIRE WI M 37 Hants. Barton Stacey 1 John B. WILTSHIRE S 2 Hants. Barton Stacey 1 Ethel M. -

The Test Way, Longparish to Chilbolton

The Test Way, Longparish to Chilbolton Distance: 5 miles Start: Longparish A 44 mile long-distance walking route takes you from its dramatic start, high on the chalk downs at Inkpen, to follow much of the course of the River Test to Eling where its tidal waters flow into Southampton Water. This is without doubt Hampshire's longest and finest chalk stream, world famous for its superb trout fishing The way has been divided into 8 sections, each providing a really good day-out. Choose between water meadows or tidal marshes, riverbank picnics or cosy pubs, steep hills with exhilarating views or cool peaceful woodland. The route passes through some of the most picturesque villages in Hampshire, strewn with listed buildings, historic churches and houses. It is well sign posted and waymarked. Horse-riders and cyclists can also use some parts. Directions Walk through the pretty hamlet of Forton on the banks of the Test. You then re-enter the lovely Harewood Forest on Second World War concrete tracks, used to conceal vehicles from snooping enemy aircraft. Leave the woods and walk along pleasant old farm lanes back into the valley to Wherwell. The route runs behind the village, but much more scenic is a walk down the main street. Cross the different branches of the river via footbridges, past Chilbolton Common with its vast variety of flora and fauna. Skirting Chilbolton and its Observatory you will reach West Down. Test Way - Longparish to Chilbolton ( (! (! ! Route Start ( !(S ! Footpath !(S ( ! ( Bridleway ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( / ! Restricted Byway Byway Open to All Traffic (! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( (! ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! (! (! ( ! ( ! ( ! ( ! (! (! (! (! 0 0.25 0.5 0.75 1 Miles © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey [100019180]. -

1988 Booklet

0458 £1 jfelb August 29th 1988 ADMISSION FREE FIELD OPENS 1.45p.m. FREE WITH EVERY VOLVO 300 SERIES FROM WILL EMMINS.. ..A CAR FULL OF CARE Not only will you be given Volvo's Lifetime Care commitment and Careline Package with FREE R.A.C. membership at Will Emmins garage but also the constant attention of our Service Receptionist, Sales Manager, Service Manager and Service Engineers-if you need them! With the Volvo 300 series starting at £6,975 ex works we're confident that all this care will mean trouble free motoring for years to come... but isn't it good to know it's right there with you, wherever Will Emmins Ltd., Salisbury Road, Abbotts Ann, Andover. Tel. (0264) 710248 'Charles and Pam' The story of a much respected couple. At the end of Wherwell lie two tiny hamlets, unknown except to natives, called Cottonworth and Fullerton. Cottonworth is, in fact, a postal address although it consists of ten houses at most and is completely baffling even to Andover taxi drivers who have driven around the area all their working lives. It is not unknown however to flocks of American tourists who appear every summer eager to see their ancestral home. These hamlets consist almost entirely of the properties owned by Fullerton Arms Limited, a company set up by Major Charles Liddell to handle an estate left to him by his great uncle. The estate was divided between two brothers and stretches between Cottonworth, at the far end of Wherwell, to the Clatfords, The part of it that is clustered around the winding river Anton before it joins the Test is farmed by Major Charles Liddell who has lived at Fullerton Grange with his wife Pamela since he inherited the estate in 1957. -

Service 15 Stockbridge to Andover Via Chilbolton, Wherwell and the Clatfords Via the Clatfords, Wherwell and Chilbolton Includ

Service 15 Andover to Stockbridge via The Clatfords, Wherwell and Chilbolton Including journeys on Service 87 to Salisbury Monday to Saturday, no service Sundays or Bank Holidays From 1st September 2015 87 15 87 15 15 87 15 www.wheelerstravel.co.uk SAT NS Andover Bus Station, Stand F 1000 1130 1200 1320 1450 1645 1650 Andover, Floral Way Aster Court 1006 1136 1206 1326 1458$ R 1658$ Andover, Anna Valley, Kings Mead 1014 1214 1655 Abbots, Ann, The Eagle 1018 1218 1659 Middle Wallop, Tne George Inn 1025 1225 1706 Over Wallop, Post Office 1027 1227 …. Salisbury, Endless Street 1120 1320 1748 Upper Clatford, Crook & Shears 1144 1334 Goodworth Clatford, Royal Oak 1148 1348 Fullerton, Cottonworth 1150 1350 Wherwell, Bus shelter 1154 1344 Chilbolton, Branksome Avenue 1200 1350 Stockbridge, Town Hall 1208 1358 see notes below The 1208 arrival at Stockbridge Town Hall continues to Winchester as service 16 via Houghton, Broughton and Kings Somborne The 1358 arrival at Stockbridge Town Hall connects with service 16 for Houghton and Broughton, it is necessary to change buses at this time Service 15 Stockbridge to Andover via Chilbolton, Wherwell and The Clatfords Including journeys on Service 87 from Salisbury 15 87 15 87 87 15 87 15 SAT NS Stockbridge - Church 0915 1105 Chilbolton - Branksome Ave 0923 1113 Wherwell - Bus Shelter 0929 1119 Fullerton, Cottonworth 0931 1121 Goodworth Clatford - Royal Oak 0935 1125 Upper Clatford - Crook & Shears 0939 1129 Salisbury, Endless Street 0933 1127 1327 1535 Over Wallop, Post Office 1014 1214 1414 …. Middle -

Xploring Exploring

82188 PRINTED BY HAMPSHIRE PRINTING SERVICES 01962 870099 82188 PRINTED BY HAMPSHIRE PRINTING SERVICES information contained within this leaflet. leaflet. this within contained information County Council is unable to accept any responsibility for accident or loss resulting from following the the following from resulting loss or accident for responsibility any accept to unable is Council County routes promoted in this leaflet. Every care has been taken in the preparation of this leaflet, but Hampshire Hampshire but leaflet, this of preparation the in taken been has care Every leaflet. this in promoted routes endeavours to maintain all rights of way to a high standard, additional resources are not allocated to to allocated not are resources additional standard, high a to way of rights all maintain to endeavours Scheme. The routes described have been put forward by the Parish Council. Whilst the County Council Council County the Whilst Council. Parish the by forward put been have described routes The Scheme. Disclaimer: Published by Wherwell Parish Council and Hampshire County Council, through the Small Grants Grants Small the through Council, County Hampshire and Council Parish Wherwell by Published Disclaimer: OS Explorer Map 131 covers this area this covers 131 Map Explorer OS www.hants.gov.uk/countryside 0845 603 5636 603 0845 A leaflet can be downloaded at www.hants.gov.uk/walking. at downloaded be can leaflet A please contact Hampshire County Council: Council: County Hampshire contact please Beacon to Eling also passes through the Parish. Parish. the through passes also Eling to Beacon For further information about access to the countryside countryside the to access about information further For The Test Way, a 44 mile long-distance walk from Inkpen Inkpen from walk long-distance mile 44 a Way, Test The www.hants.gov.uk/maps/paths the magnificent Harewood Forest.