A Valgrind Tool to Computethe Working Set of a Software Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2006.14147V2 [Cs.CR] 26 Mar 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6988/arxiv-2006-14147v2-cs-cr-26-mar-2021-106988.webp)

Arxiv:2006.14147V2 [Cs.CR] 26 Mar 2021

FastSpec: Scalable Generation and Detection of Spectre Gadgets Using Neural Embeddings M. Caner Tol Berk Gulmezoglu Koray Yurtseven Berk Sunar Worcester Polytechnic Institute Iowa State University Worcester Polytechnic Institute Worcester Polytechnic Institute [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Several techniques have been proposed to detect [4] are implemented against the SGX environment and vulnerable Spectre gadgets in widely deployed commercial even remotely over the network [5]. These attacks show software. Unfortunately, detection techniques proposed so the applicability of Spectre attacks in the wild. far rely on hand-written rules which fall short in covering Unfortunately, chip vendors try to patch the leakages subtle variations of known Spectre gadgets as well as demand one-by-one with microcode updates rather than fixing a huge amount of time to analyze each conditional branch the flaws by changing their hardware designs. Therefore, in software. Moreover, detection tool evaluations are based developers rely on automated malware analysis tools to only on a handful of these gadgets, as it requires arduous eliminate mistakenly placed Spectre gadgets in their pro- effort to craft new gadgets manually. grams. The proposed detection tools mostly implement In this work, we employ both fuzzing and deep learning taint analysis [6] and symbolic execution [7], [8] to iden- techniques to automate the generation and detection of tify potential gadgets in benign applications. However, Spectre gadgets. We first create a diverse set of Spectre-V1 the methods proposed so far are associated with two gadgets by introducing perturbations to the known gadgets. shortcomings: (1) the low number of Spectre gadgets Using mutational fuzzing, we produce a data set with more prevents the comprehensive evaluation of the tools, (2) than 1 million Spectre-V1 gadgets which is the largest time consumption exponentially increases when the binary Spectre gadget data set built to date. -

Automatic Benchmark Profiling Through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin, Vania Marangozova-Martin

Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin, Vania Marangozova-Martin To cite this version: Alexis Martin, Vania Marangozova-Martin. Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis. [Research Report] RR-8889, Inria - Research Centre Grenoble – Rhône-Alpes; Université Grenoble Alpes; CNRS. 2016. hal-01292618 HAL Id: hal-01292618 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01292618 Submitted on 24 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin , Vania Marangozova-Martin RESEARCH REPORT N° 8889 March 23, 2016 Project-Team Polaris ISSN 0249-6399 ISRN INRIA/RR--8889--FR+ENG Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin ∗ † ‡, Vania Marangozova-Martin ∗ † ‡ Project-Team Polaris Research Report n° 8889 — March 23, 2016 — 15 pages Abstract: Benchmarking has proven to be crucial for the investigation of the behavior and performances of a system. However, the choice of relevant benchmarks still remains a challenge. To help the process of comparing and choosing among benchmarks, we propose a solution for automatic benchmark profiling. It computes unified benchmark profiles reflecting benchmarks’ duration, function repartition, stability, CPU efficiency, parallelization and memory usage. -

Automatic Benchmark Profiling Through Advanced Trace Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Hal - Université Grenoble Alpes Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin, Vania Marangozova-Martin To cite this version: Alexis Martin, Vania Marangozova-Martin. Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis. [Research Report] RR-8889, Inria - Research Centre Grenoble { Rh^one-Alpes; Universit´eGrenoble Alpes; CNRS. 2016. <hal-01292618> HAL Id: hal-01292618 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01292618 Submitted on 24 Mar 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin , Vania Marangozova-Martin RESEARCH REPORT N° 8889 March 23, 2016 Project-Team Polaris ISSN 0249-6399 ISRN INRIA/RR--8889--FR+ENG Automatic Benchmark Profiling through Advanced Trace Analysis Alexis Martin ∗ † ‡, Vania Marangozova-Martin ∗ † ‡ Project-Team Polaris Research Report n° 8889 — March 23, 2016 — 15 pages Abstract: Benchmarking has proven to be crucial for the investigation of the behavior and performances of a system. However, the choice of relevant benchmarks still remains a challenge. To help the process of comparing and choosing among benchmarks, we propose a solution for automatic benchmark profiling. -

Generic User-Level PCI Drivers

Generic User-Level PCI Drivers Hannes Weisbach, Bj¨orn D¨obel, Adam Lackorzynski Technische Universit¨at Dresden Department of Computer Science, 01062 Dresden {weisbach,doebel,adam}@tudos.org Abstract Linux has become a popular foundation for systems with real-time requirements such as industrial control applications. In order to run such workloads on Linux, the kernel needs to provide certain properties, such as low interrupt latencies. For this purpose, the kernel has been thoroughly examined, tuned, and verified. This examination includes all aspects of the kernel, including the device drivers necessary to run the system. However, hardware may change and therefore require device driver updates or replacements. Such an update might require reevaluation of the whole kernel because of the tight integration of device drivers into the system and the manyfold ways of potential interactions. This approach is time-consuming and might require revalidation by a third party. To mitigate these costs, we propose to run device drivers in user-space applications. This allows to rely on the unmodified and already analyzed latency characteristics of the kernel when updating drivers, so that only the drivers themselves remain in the need of evaluation. In this paper, we present the Device Driver Environment (DDE), which uses the UIO framework supplemented by some modifications, which allow running any recent PCI driver from the Linux kernel without modifications in user space. We report on our implementation, discuss problems related to DMA from user space and evaluate the achieved performance. 1 Introduction in safety-critical systems would need additional au- dits and certifications to take place. -

Building Embedded Linux Systems ,Roadmap.18084 Page Ii Wednesday, August 6, 2008 9:05 AM

Building Embedded Linux Systems ,roadmap.18084 Page ii Wednesday, August 6, 2008 9:05 AM Other Linux resources from O’Reilly Related titles Designing Embedded Programming Embedded Hardware Systems Linux Device Drivers Running Linux Linux in a Nutshell Understanding the Linux Linux Network Adminis- Kernel trator’s Guide Linux Books linux.oreilly.com is a complete catalog of O’Reilly’s books on Resource Center Linux and Unix and related technologies, including sample chapters and code examples. ONLamp.com is the premier site for the open source web plat- form: Linux, Apache, MySQL, and either Perl, Python, or PHP. Conferences O’Reilly brings diverse innovators together to nurture the ideas that spark revolutionary industries. We specialize in document- ing the latest tools and systems, translating the innovator’s knowledge into useful skills for those in the trenches. Visit con- ferences.oreilly.com for our upcoming events. Safari Bookshelf (safari.oreilly.com) is the premier online refer- ence library for programmers and IT professionals. Conduct searches across more than 1,000 books. Subscribers can zero in on answers to time-critical questions in a matter of seconds. Read the books on your Bookshelf from cover to cover or sim- ply flip to the page you need. Try it today for free. main.title Page iii Monday, May 19, 2008 11:21 AM SECOND EDITION Building Embedded Linux SystemsTomcat ™ The Definitive Guide Karim Yaghmour, JonJason Masters, Brittain Gilad and Ben-Yossef, Ian F. Darwin and Philippe Gerum Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Sebastopol • Taipei • Tokyo Building Embedded Linux Systems, Second Edition by Karim Yaghmour, Jon Masters, Gilad Ben-Yossef, and Philippe Gerum Copyright © 2008 Karim Yaghmour and Jon Masters. -

Lilypond Informations Générales

LilyPond Le syst`eme de notation musicale Informations g´en´erales Equipe´ de d´eveloppement de LilyPond Copyright ⃝c 2009–2020 par les auteurs. This file documents the LilyPond website. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.1 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections. A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. Pour LilyPond version 2.21.82 1 LilyPond ... la notation musicale pour tous LilyPond est un logiciel de gravure musicale, destin´e`aproduire des partitions de qualit´e optimale. Ce projet apporte `al’´edition musicale informatis´ee l’esth´etique typographique de la gravure traditionnelle. LilyPond est un logiciel libre rattach´eau projet GNU (https://gnu. org). Plus sur LilyPond dans notre [Introduction], page 3, ! La beaut´epar l’exemple LilyPond est un outil `ala fois puissant et flexible qui se charge de graver toutes sortes de partitions, qu’il s’agisse de musique classique (comme cet exemple de J.S. Bach), notation complexe, musique ancienne, musique moderne, tablature, musique vocale, feuille de chant, applications p´edagogiques, grands projets, sortie personnalis´ee ainsi que des diagrammes de Schenker. Venez puiser l’inspiration dans notre galerie [Exemples], page 6, 2 Actualit´es ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, ⟨undefined⟩ [News], page ⟨undefined⟩, [Actualit´es], page 103, i Table des mati`eres -

Development Tools for the Kernel Release 4.13.0-Rc4+

Development tools for the Kernel Release 4.13.0-rc4+ The kernel development community Sep 05, 2017 CONTENTS 1 Coccinelle 3 1.1 Getting Coccinelle ............................................. 3 1.2 Supplemental documentation ...................................... 3 1.3 Using Coccinelle on the Linux kernel .................................. 4 1.4 Coccinelle parallelization ......................................... 4 1.5 Using Coccinelle with a single semantic patch ............................ 5 1.6 Controlling Which Files are Processed by Coccinelle ......................... 5 1.7 Debugging Coccinelle SmPL patches .................................. 5 1.8 .cocciconfig support ............................................ 6 1.9 Additional flags ............................................... 7 1.10 SmPL patch specific options ....................................... 7 1.11 SmPL patch Coccinelle requirements .................................. 7 1.12 Proposing new semantic patches .................................... 7 1.13 Detailed description of the report mode ................................ 7 1.14 Detailed description of the patch mode ................................ 8 1.15 Detailed description of the context mode ............................... 9 1.16 Detailed description of the org mode .................................. 9 2 Sparse 11 2.1 Using sparse for typechecking ...................................... 11 2.2 Using sparse for lock checking ...................................... 11 2.3 Getting sparse .............................................. -

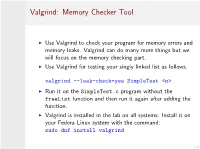

Valgrind: Memory Checker Tool

Valgrind: Memory Checker Tool I Use Valgrind to check your program for memory errors and memory leaks. Valgrind can do many more things but we will focus on the memory checking part. I Use Valgrind for testing your singly linked list as follows. valgrind --leak-check=yes SimpleTest <n> I Run it on the SimpleTest.c program without the freeList function and then run it again after adding the function. I Valgrind is installed in the lab on all systems. Install it on your Fedora Linux system with the command: sudo dnf install valgrind 1/8 Valgrind: Overview I Extremely useful tool for any C/C++ programmer I Mostly known for Memcheck module, which helps find many common memory related problems in C/C++ code I Supports X86/Linux, AMD64/Linux, PPC32/Linux, PPC64/Linux and X86/Darwin (Mac OS X) I Available for X86/Linux since ~2003, actively developed 2/8 Sample (Bad) Code I We will use the following code for demonstration purposes:: The code can be found in the examples at C-examples/debug/valgrind. 1 #include <stdio.h> 2 #include <stdlib.h> 3 #define SIZE 100 4 int main() { 5 int i, sum = 0; 6 int *a = malloc(SIZE); 7 for (i = 0; i < SIZE; ++i) 8 sum += a[i]; 9 a [26] = 1; 10 a = NULL ; 11 if (sum > 0) printf("Hi!\n"); 12 return 0; 13 } I Contains many bugs. Compiles without warnings or errors. Run it under Valgrind as shown below: valgrind --leak-check=yes sample 3/8 Invalid Read Example ==17175== Invalid read of size 4 ==17175== at 0x4005C0: main (sample.c:9) ==17175== Address 0x51f60a4 is 0 bytes after a block of size 100 alloc’d ==17175== -

Using Valgrind to Detect Undefined Value Errors with Bit-Precision

Using Valgrind to detect undefined value errors with bit-precision Julian Seward Nicholas Nethercote OpenWorks LLP Department of Computer Sciences Cambridge, UK University of Texas at Austin [email protected] [email protected] Abstract We present Memcheck, a tool that has been implemented with the dynamic binary instrumentation framework Val- grind. Memcheck detects a wide range of memory errors 1.1 Basic operation and features in programs as they run. This paper focuses on one kind Memcheck is a dynamic analysis tool, and so checks pro- of error that Memcheck detects: undefined value errors. grams for errors as they run. Memcheck performs four Such errors are common, and often cause bugs that are kinds of memory error checking. hard to find in programs written in languages such as C, First, it tracks the addressability of every byte of mem- C++ and Fortran. Memcheck's definedness checking im- ory, updating the information as memory is allocated and proves on that of previous tools by being accurate to the freed. With this information, it can detect all accesses to level of individual bits. This accuracy gives Memcheck unaddressable memory. a low false positive and false negative rate. Second, it tracks all heap blocks allocated with The definedness checking involves shadowing every malloc(), new and new[]. With this information it bit of data in registers and memory with a second bit can detect bad or repeated frees of heap blocks, and can that indicates if the bit has a defined value. Every value- detect memory leaks at program termination. creating operation is instrumented with a shadow oper- Third, it checks that memory blocks supplied as argu- ation that propagates shadow bits appropriately. -

Table of Contents

A Comprehensive Introduction to Vista Operating System Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Windows Vista Chapter 2 - Development of Windows Vista Chapter 3 - Features New to Windows Vista Chapter 4 - Technical Features New to Windows Vista Chapter 5 - Security and Safety Features New to Windows Vista Chapter 6 - Windows Vista Editions Chapter 7 - Criticism of Windows Vista Chapter 8 - Windows Vista Networking Technologies Chapter 9 -WT Vista Transformation Pack _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ Abstraction and Closure in Computer Science Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Abstraction (Computer Science) Chapter 2 - Closure (Computer Science) Chapter 3 - Control Flow and Structured Programming Chapter 4 - Abstract Data Type and Object (Computer Science) Chapter 5 - Levels of Abstraction Chapter 6 - Anonymous Function WT _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ Advanced Linux Operating Systems Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Introduction to Linux Chapter 2 - Linux Kernel Chapter 3 - History of Linux Chapter 4 - Linux Adoption Chapter 5 - Linux Distribution Chapter 6 - SCO-Linux Controversies Chapter 7 - GNU/Linux Naming Controversy Chapter 8 -WT Criticism of Desktop Linux _____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES _____________________ Advanced Software Testing Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Software Testing Chapter 2 - Application Programming Interface and Code Coverage Chapter 3 - Fault Injection and Mutation Testing Chapter 4 - Exploratory Testing, Fuzz Testing and Equivalence Partitioning Chapter 5 -

IBM Presentations

Linux on System z debugging with Valgrind Christian Bornträger <[email protected]> © 2012 IBM Corporation Linux on System z debugging with Valgrind Trademarks The following are trademarks of the International Business Machines Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. AIX* IBM* PowerVM System z10 z/OS* BladeCenter* IBM eServer PR/SM WebSphere* zSeries* DataPower* IBM (logo)* Smarter Planet z9* z/VM* DB2* InfiniBand* System x* z10 BC z/VSE FICON* Parallel Sysplex* System z* z10 EC GDPS* POWER* System z9* zEnterprise HiperSockets POWER7* * Registered trademarks of IBM Corporation The following are trademarks or registered trademarks of other companies. Adobe, the Adobe logo, PostScript, and the PostScript logo are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States, and/or other countries. Cell Broadband Engine is a trademark of Sony Computer Entertainment, Inc. in the United States, other countries, or both and is used under license there from. Java and all Java-based trademarks are trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the United States, other countries, or both. Microsoft, Windows, Windows NT, and the Windows logo are trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States, other countries, or both. Windows Server and the Windows logo are trademarks of the Microsoft group of countries. InfiniBand is a trademark and service mark of the InfiniBand Trade Association. Intel, Intel logo, Intel Inside, Intel Inside logo, Intel Centrino, Intel Centrino logo, Celeron, Intel Xeon, Intel SpeedStep, Itanium, and Pentium are trademarks or registered trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries in the United States and other countries. -

Valgrind Vs. KVM Christian Bornträger

Valgrind vs. KVM Christian Bornträger IBM Deutschland Research & Development GmbH [email protected] Co-maintainer KVM and QEMU/KVM for s390x (aka System z, zEnterprise, IBM mainframe) Valgrind vs. KVM based QEMU http://wiki.qemu.org/Debugging_with_Valgrind says: “valgrind really doesn't function well when using KVM so it's advised to use TCG” ● So: my presentation ends here.... ● Really? Valgrind overview (1/4) ● “Valgrind is a tool for finding memory leaks” ? ● Valgrind is an instrumentation framework for building dynamic analysis tools – works on compiled binary code - no source checker – “understands” most instructions and most system calls ● Used as debugging tool Valgrind overview (2/4) VALGRIND LINUX Replace some of the QEMU Library calls by using a Preload library [...] 00000000001fefd3 <main>: push %rbp mov %rsp,%rbp translation e c push %rbx into intermediate a sub $0x338,%rsp f mov %edi,-0x314(%rbp) representation (IR) r mov %rsi,-0x320(%rbp) e t mov %rdx,-0x328(%rbp) n mov %fs:0x28,%rax i mov %rax,-0x18(%rbp) l xor %eax,%eax instrumentation l movq $0x0,-0x190(%rbp) a movq $0x0,-0x1a8(%rbp) c movq $0x0,-0x1c0(%rbp) movq $0x0,-0x1d8(%rbp) m movq $0x0,-0x1e0(%rbp) e [...] translation t to machine code s y S Host binary code Coregrind (scheduling, plumbing, system calls...) Valgrind overview (3/4) ● The instrumentation is done with tools – Memcheck (default): detects memory-management problems – Cachegrind: cache profiler – massif: Heap profiler – Helgrind/DRD: Thread race debugger – …. ● Usage is simple: # valgrind [valgrind