Laurie Periello-Davis, Traveling Fellowship in Architectural Design and Technology, 1990

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

UN Delegates Lounge

OMA’s layout design trisects the central section of the UN North Delegates Lounge, with private seating along the edges and communal furniture in the middle. UN North Delegates Lounge Hella Jongerius assembled a force of the Netherlands’ top designers including Irma Boom and Rem Koolhaas for the prestigious renovation of the North Delegates Lounge in the UN Building in New York. WORDS Oli Stratford PHOTOS Frank Oudeman 152 Disegno. UN NORTH DELEGATES LOUNGE UN NORTH DELEGATES LOUNGE Disegno. 153 The east window is veiled by the Knots & Beads curtain by Hella Jongerius and Dutch ceramics company Royal Tichelaar Makkum. In front is the UN Lounge chair by Jongerius for Vitra. uring the summer of 1986, Hella Jongerius1 was backpacking across America. She was 23 years old, two years shy of enrolling at Design Academy Eindhoven,2 1 Hella Jongerius (b. 1963) is and picking her way from state to state. Three months in, she reached New York. a Dutch product and furniture designer whose Jongeriuslab studio is based in Berlin. She She had a week in the city, but her money had run out. So, broke, Jongerius went to Turtle Bay, is known for furniture and a Manhattan neighbourhood on the bank of the East River and the home of the UN Building, a accessory design that steel and glass compound built in the 1950s to house the United Nations.3 “I’d gone down there combines industrial manufacture with craft to see the building and I was impressed of course,” says Jongerius. “It’s a beautiful building. But sensibilities and techniques. -

Old Buildings, New Views Recent Renovations Around Town Have Uncovered Views of Manhattan That Had Been Hiding in Plain Sight

The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 Old Buildings, New Views Recent renovations around town have uncovered views of Manhattan that had been hiding in plain sight. By Caroline Biggs Impressions: 43,264,806 While New York City’s skyline is ever changing, some recent construction and additions to historic buildings across the city have revealed some formerly hidden, but spectacular, views to the world. These views range from close-up looks at architectural details that previously might have been visible only to a select few, to bird’s-eye views of towers and cupolas that until The New York Times: Real Estate May 7, 2021 recently could only be viewed from the street. They provide a novel way to see parts of Manhattan and shine a spotlight on design elements that have largely been hiding in plain sight. The structures include office buildings that have created new residential spaces, like the Woolworth Building in Lower Manhattan; historic buildings that have had towers added or converted to create luxury housing, like Steinway Hall on West 57th Street and the Waldorf Astoria New York; and brand-new condo towers that allow interesting new vantages of nearby landmarks. “Through the first decades of the 20th century, architects generally had the belief that the entire building should be designed, from sidewalk to summit,” said Carol Willis, an architectural historian and founder and director of the Skyscraper Museum. “Elaborate ornament was an integral part of both architectural design and the practice of building industry.” In the examples that we share with you below, some of this lofty ornamentation is now available for view thanks to new residential developments that have recently come to market. -

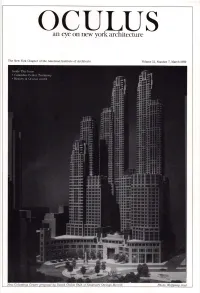

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Art I N Public Places

PITTSBURGH PITTSBURGH ART ART IN PUBLIC PLACES IN PUBLIC PLACES DOWNTOWN WALKING TOUR OFFICE OF PUBLIC ART PITTSBURGH ART IN PUBLIC PLACES DOWNTOWN WALKING TOUR FOURTH EDITION Copyright ©2016 by the Office of Public Art, CONTENTS a partnership between the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council and the City of Pittsburgh Department of City Planning 4 CULTURAL DISTRICT PROJECT DIRECTOR Renee Piechocki 38 GRANT STREET CORRIDOR PROJECT DEVELOPMENT Rachel Klipa DESIGN Little Kelpie 84 RETAIL DISTRICT AND FIRSTSIDE PHOTOGRAPHY Renee Rosensteel, 118 NORTH SHORE except where noted 152 NORTHSIDE This book is designed to connect people with art in public places in Downtown Pittsburgh. In addition to art, noteworthy architecture, landscape architecture, and cultural objects have been included based on their proximity to the artworks in the guide. Each walk takes approximately 80–120 minutes. Allow more time for contemplation and exploring. Free copies of this walking tour can be downloaded from the Office of Public Art’s website, publicartpittsburgh.org. Learn more about art in public places in the region by visiting pittsburghartplaces.org. WALKING TOUR THREE RETAIL DISTRICT AND FIRSTSIDE Art in these districts is found amidst soaring office towers, French and Indian War sites, retail establishments, and a historic financial district. PITTSBURGH RECOLLECTIONS PITTSBURGH PEOPLE RETAIL DISTRICT AND FIRSTSIDE 85 JACKSONIA ST FEDERAL ST MATTRESS FACTORY ARCH ST SAMPSONIA SHERMAN AVE PALO ALTO ST RESACA ST E. NORTH AVE N TAYLOR AVE MONTEREY ST BUENA VISTA ST BRIGHTON RD JAMES ST CEDAR AVE PENNSYLVANIA AVE FORELAND ST W. NORTH AVE N. COMMONS NATIONAL AVIARY ARCH ST E. OHIO ST LIBRARY & NEW HAZLETT THEATER CHILDRENS MUSEUM BRIGHTON RD W. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

Pratt Manhattan Gallery and Van Alen Institute to Present an Exhibition That Examines the Worldwide Phenomenon of Urban Declin

MEDIA CONTACTS Pratt Manhattan Gallery Pratt Manhattan Gallery Mara McGinnis Tel: 718.636.3471 and Van Alen Institute to Email: [email protected] Van Alen Institute present an exhibition that Antoine Vigne, Blue Medium, Inc. Tel: 212.675.1800 examines the worldwide Email: [email protected] Project Office Shrinking Cities phenomenon of urban Astrid Herbold Eisenacher Strasse 74 Berlin, D-10823 decline and possibilities Tel: +49 (30) 81 82 19 06 Email: [email protected] of creative intervention Shrinking Cities, International Research NEW YORK, N.Y., November 15, 2006 —While December 8, 2006 – January 21, 2007 international urban discourse focuses exclusively on the Opening Reception: growing megalopolises, zones of shrinkage have been 5:30 – 7:30 PM, Thursday, December 7 forming and are generally ignored. Shrinking Cities, a Van Alen Institute four year project of the German Federal Cultural 30 West 22nd Street, 6th floor Foundation, has investigated the worldwide phenomenon New York, NY 10010 212.924.7000 of urban shrinkage by focusing on four urban regions: Detroit (USA), Halle/Leipzig (Germany), Manchester/ Shrinking Cities, Interventions Liverpool (U.K.), and Ivanovo (Russia). December 8, 2006 – February 17, 2007 Opening Reception: The project included two phases, during which a network of 6:30 – 8:30 PM, Thursday, December 7 more than 200 artists, architects, academics, and local initiatives Gallery: Monday – Friday, 10 AM – 6 PM approached the question, “How can we grasp urban decline and Pratt Manhattan Gallery what do we do with shrinking cities?” The results have been 144 West 14th Street, 2nd floor presented in two exhibitions, several books, digital publications, New York, NY 10011 and numerous public events. -

Exhibition Brochure Is There A

‘Is There Anyone Out There?’ Documenting Birmingham’s Alternative Music Scene 1986-1990 Acknowledgements and Thanks Thanks to Dave Travis for opening up his incredible archive and recalling the histories associated with The Click Club. Likewise, thanks to Steve (Geoffrey S. Kent) Coxon for his generous insights and for taking a road trip to tell us almost everything. Thanks on behalf of all Click Clubbers to Travis and Coxon for starting it and for program- ming so many memorable nights for creating an environment for people to make their own. Thanks to Dave Chambers (and Andy Morris), Donna Gee, Bridget Duffy and Bryan Taylor Thankswho provided to all of particular those who materials contributed for the written exhibition memories: (Bryan Steve for some Byrne; fine Craig writing!). Hamilton; Andrew Davies; Sarah Heyworth; Neil Hollins; Angela Hughes; Rhodri Marsden; Dave Newton; Daniel Rachel; Lara Ratnaraja; Spencer Roberts; John Taggart; Andy Tomlinson and Maria Williams. Acknowledgements to the many contributors to Facebook Groups for The Click Club and Birmingham Music Archive. John Hall and Ixchelt Corbett Mighty Mighty: Russell Burton, Mick Geoghegan, Pete Geoghegan, D J Hennessy Hugh McGuinness. Lyle Bignon, Boris Barker, Darren Elliot, Graham Bradbury, Richard March Yasmin Baig-Clifford (Vivid Projects), John Reed at Cherry Red Records, Ernie Cartwright, Birmingham Music Archive, Justin Sanders, Naomi Midgley. Neil Hollins for production of the podcast interview with Steve Coxon and Dave Travis. Digital Print Services who produced the images. Special thanks to: Neil Taylor, Ellie Gibbons, Anna Pirvola, Aidan Mooney and Beth Kane. What was The Click Club? Established in 1986 by Dave Travis and Steve Coxon, ‘The Click Club’ was the name of a concert venue and disco associated with Birmingham’s alternative music culture. -

March 2010 for on Line Alumni Notes

Alumni Notes – March 2010 news items collected over the past year 1946 I.M. Pei, MArch, received the Royal Institute of British Architects’ prestigious Royal Gold Medal, one of the industry’s most lauded awards given in recognition of an architect’s lifetime work. Pei Cobb Freed & Partners was named one of six architecture teams that will compete to design the National Museum of African American History and Culture on the Mall in the shadow of the Washington Monument. 1954 Maki & Associates, the firm of Fumihiko Maki, MArch, presented at the Icon track of The Design Conference in Mumbai, hosted by 361˚: The Degree of Difference. Maki’s new design for the MIT Media Lab was featured in an article in the Boston Sunday Globe by Robert Campbell, MArch ’67. Maki recently spoke at the GSD in conversation with Mark Mulligan, GSD Adjunct Associate Professor of Architecture. 1957 Frank Gehry, DES, and his houses are the subject of a new book, Frank Gehry: The Houses, by Mildred Friedman. This is the first title devoted exclusively to the residential works of Gehry. In December 2009, the Signature Theatre Company announced that it raised $41 million of the $60 million goal for its new theater designed by Gehry. The City of New York is contributing $25 million to the fulfillment of the project. Gehry also designed a unique clubhouse for the Saadiyat Beach Golf Club, the only beachfront golf course in the Persian Gulf. Gehry appeared in September at the GSD in a public conversation with Joe Brown as part of the Design Firm Leadership Conference. -

2021 NYYC Foundation Newsletter Issue #2

FOUNDATION CORNER THE ILLUMINATING REVIVAL OF THE PALM CAFÉ by Jill Connors ONE OF THE MOST ENCHANTING ROOMS AT THE 44TH STREET CLUBHOUSE REGAINS ITS ORIGINAL LUSTER, AND THEN SOME. Bold design stands the test of time, and nowhere is this truer than at the 44th Street Clubhouse, which this year celebrates its 120th magnificent year. Splendid buildings require care and attention—to every plaster molding, carved-wood bracket, and cast-iron balustrade. The remarkable care that the New York Yacht Club has provided over the years is the reason this Warren & Wetmore-designed exemplar of Beaux Arts style has survived so grandly. As Commodore Christopher J. Culver said on the building’s anniversary in January, “It’s an honor for all of us to play a role in preserving this Clubhouse.” C2 Limited’s interior-design scheme for the renewed Palm Café includes casual seating near the original ban- quettes and a color scheme evocative of an early 1900s conservatory. LIMITED DESIGN ASSOCIATES & BRYN BACHMAN & BRYN LIMITED DESIGN ASSOCIATES 2 C 14 NEW YORK YACHT CLUB FOUNDATION CORNER The New York Yacht Club was wearing thin and the Foundation is particularly lighting gave no hint of the important in this regard, original natural light that as it was created in 2007 would have made the room for the sole purpose of so pleasurable. A further maintaining both of the issue was the lack of heating club’s historic properties: the or cooling in the space. All 44th Street Clubhouse and these issues fell neatly under Newport’s Harbour Court. -

Congratulations to the 2019 AIA New York State Design & Honor Award

Congratulations to the 2019 AIA New York State Design & Honor Award Winners! The 2019 AIA New York State Design & Honor Award recipients were recognized at a luncheon held on December 6, 2019 in White Plains, NY. Annually since 1968, AIA New York State’s Annual Design Awards celebrate local, national and international projects that achieve architectural excellence designed by architects throughout New York State. Twenty five projects were recognized for Citation, Merit and Honor Awards in the following categories: Adaptive Reuse/Historic Preservation, Commercial/Industrial, Institutional, Interiors, International, Pro Bono Projects, Residential, Sole Practitioner, Unbuilt and Urban Planning/Design. The Design Awards Jury, including Jury Chair Chris Dawson, AIA of Chris Dawson Architect; Jen Zaborney of Best Space; Joseph Biondo, FAIA of Spillman Farmer Architects; and Peter Bohlin, FAIA of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson, had the challenge of choosing a handful of winners out of almost three hundred submissions. Out of the 25 award recipients, the jury also selected one project considered to be the “Best of the Best.” This year’s Mark Vincent Kruse, AIA, 2019 AIANYS President recipient is The Statue of Liberty Museum, designed presents the "Best of the Best" Award to Brandon Massey, AIA of FXCollaborative for the Statue of by FXCollaborative. Liberty Museum. The jury members stated, “Great architecture has the potential to disappear from public sight when the line between building and landscape are blurred. The Statue of Liberty Museum is conceived with great purpose and resolve and elevates itself to much more than a history museum.” AIA New York State’s Annual Honor Awards celebrate emerging professionals, architects, firms and educators throughout New York State that have contributed significantly to the profession of F. -

The Social and Political Thought of Paul Goodman

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1980 The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman. Willard Francis Petry University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Petry, Willard Francis, "The aesthetic community : the social and political thought of Paul Goodman." (1980). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2525. https://doi.org/10.7275/9zjp-s422 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DATE DUE UNIV. OF MASSACHUSETTS/AMHERST LIBRARY LD 3234 N268 1980 P4988 THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS February 1980 Political Science THE AESTHETIC COMMUNITY: THE SOCIAL AND POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PAUL GOODMAN A Thesis Presented By WILLARD FRANCIS PETRY Approved as to style and content by: Dean Albertson, Member Glen Gordon, Department Head Political Science n Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.Org/details/ag:ptheticcommuni00petr . The repressed unused natures then tend to return as Images of the Golden Age, or Paradise, or as theories of the Happy Primitive. We can see how great poets, like Homer and Shakespeare, devoted themselves to glorifying the virtues of the previous era, as if it were their chief function to keep people from forgetting what it used to be to be a man.