The History of Atmospheric Science at NASA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Independence Day: Resurgence

INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE (2016) ● Rated PG 13 for sequences of sci fi action and destruction, and for some language ● $165,000,000 budget ● 2 hrs ● Directed by Roland Emmerich ● Produced by Lynn Harris, Matti Leshem, Douglas C. Merrifield ● The film was produced by Columbia Pictures, Sony Pictures QUICK THOUGHTS ● Phil Svitek ● Marisa Serafini ● Demetri Panos ● Sara Stretton DEVELOPMENT ● The possibility of a sequel to Independence Day had long been discussed, and the film's producer and writer, Dean Devlin, once stated that the world's reaction to the September 11 attacks influenced him to strongly consider making a sequel to the film ● Soon after the success of the first film, 20th Century Fox paid Dean Devlin a large sum of money to write a script for a sequel. However, after completing the script, Devlin didn't turn in the script and instead gave the money back to the studio, as he felt the story didn't live up to the first film. It was only approximately 15 years later, that Devlin met up with Roland Emmerich to try again, having felt that they had "cracked" a story for a sequel ● Devlin began writing an outline for a script with Emmerich, but in May 2004, Emmerich said he and Devlin had attempted to "figure out a way how to continue the story", but that this ultimately did not work, and the pair abandoned the idea ● In October 2009, Emmerich said he once again had plans for a sequel, and had since considered the idea of making two sequels to form a trilogy ● On June 24, 2011, Devlin confirmed that he and Emmerich had found an idea for the sequels and had written a treatment for it ● In October 2011, however, discussions for Will Smith returning were halted, due to Fox's refusal to provide the $50 million salary demanded by Smith for the two sequels ● Emmerich, however, made assurances that the films would be shot backtoback, regardless of Smith's involvement ○ Resurgence filmmakers were reported to be preparing versions of the film both with and without Will Smith. -

The Day After Tomorrow: Public Opinion on Climate Change

The Day After Tomorrow: Public Opinion on Climate Change by Andrew Norton and John Leaman May 2004 MORI Social Research Institute The Day After Tomorrow. Public Opinion on Climate Change Introduction This report presents the findings of recent research conducted by MORI Social Research Institute assessing public opinion on, and attitudes towards, climate change and global warming. In recent months, there has been an upsurge of interest in global warming, as highlighted by the publication of satellite evidence confirming stratospheric warming,! debate about the impact of global warming on wildlife," and dire predictions of the impacts of sea level rise#$%%% The film The Day After Tomorrow – released on 28 May – will only serve to increase media interest in this issue. This end-of-the-world disaster film provides an ecological horror story about climate change, where Los Angeles is destroyed by tornados, New York is drowned by a tidal wave and Europe freezes with the onset of a new ice age. The film will have a potential audience of 500 million people, and is set to put climate change on the “mainstream” agenda. Environmentalists hope that the Hollywood blockbuster will change people’s perceptions about climate change, while others have warned that the film is a manipulation of science to serve a political agenda. In line with international efforts to gain agreement on curbing carbon emissions – the gases that contribute towards the global warming – the Government has long been committed to moving the UK to a ‘low carbon economy’. This commitment can be traced to the climate change convention that was agreed at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.& The ratification of the Kyoto Agreement in 2002 committed the UK to reducing carbon emissions by 12.5% below 1990 levels by 2008-2012. -

Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: a People's History of S)

[PDF] Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Colin Burgess, Francis French, Paul Haney - pdf download free book Download Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) PDF, PDF Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Popular Download, Read Online Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) E-Books, Read Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Full Collection Colin Burgess, Francis French, Paul Haney, Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Full Collection, I Was So Mad Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Colin Burgess, Francis French, Paul Haney Ebook Download, Free Download Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Full Version Colin Burgess, Francis French, Paul Haney, PDF Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Free Download, PDF Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History Of S) Full Collection, Download PDF Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers Of The Space Era, 1961-1965 (Outward Odyssey: A People's History -

A Film That Could Warm up the Debate on Global Warming

The New York Times > Opinion > Editorial Observer: A Film That Could Warm Up the Debate on G... May 27, 2004 EDITORIAL OBSERVER A Film That Could Warm Up the Debate on Global Warming By ROBERT B. SEMPLE. Jr. ven as a summer disaster film, "The Day After Tomorrow" does not rank with the greats of yesteryear. Its dialogue is overwrought, its symbolism sophomoric, its subplots annoyingly irrelevant and its relationship to scientific reality tenuous at best. But the special effects are terrific, and the timing couldn't be better. Scientists, environmentalists and a few lonely politicians have been trying without great success to get the public and the Bush administration to take global warming seriously, and to inject the issue into a presidential campaign that so far seems determined to ignore it. Whatever its flaws, "The Day After Tomorrow"' could do more to elevate the issue than any number of Congressional hearings or high-minded tracts. That's one reason the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan was happy to present the premiere in a theater not far from its Hall of Biodiversity, biodiversity being one of global warming's most likely victims. It's also a reason why mainstream environmental groups have rushed to offer sage commentary on what, after all, is just a mindless summer blockbuster. One group, the Worldwatch Institute, goes so far as to offer on its Web site energy-saving tips on how to ensure "a better day after tomorrow." It exhorts the 20 million Americans the producers hope to draw to the movie to install more efficient shower heads to cut down on hot water use, and to ride bikes to the theater instead of driving. -

Nov 2019-Jan 2020 Grand

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF GRAND CINEMAS GRANDFREE NOV 2019-JAN 2020 20202020 MUSTMUST LISTLIST ONE ON ONEi with thei massivei A-list castiMIDWAY THETHE BATTLEBATTLE THATTHAT TURNEDTURNED THETHE TIDESTIDES OFOF WARWAR Movie_Guide_16.5x23.5.pdf 1 10/11/19 10:54 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K GOGRAND #alwaysentertaining SOCIALISE TALK MOVIES, WIN PRIZES @GCLEBANON CL BOOK NEVER MISS A MOVIE WITH E/TICKET, E/KIOSK AND THE GC MOBILE APP. EXPERIENCE FIRSTWORD ISSUE 126 FEAT. DOLBY ATMOS A nation makes a stand As we approach the end of an eventful 2019, we are once again LOCATIONS reminded of the power of film to inspire and move us, and to commemorate those pivotal moments in history that define nations. LEBANON KUWAIT We salute the Lebanese people, and wish one and all a prosperous GRAND CINEMAS GRAND AL HAMRA ABC VERDUN LUXURY CENTER new year that lives up to our promise and expectations for a brighter 01 795 697 +965 222 70 334 future. Here’s to the beginning of a new era in 2020. MX4D featuring MX4D ATMOS DOLBY ATMOS Our SPOTLIGHT feature is a fitting tribute to historical moments. GRAND CLASS GRAND GATE MALL Acclaimed director Roland Emmerich gathers an army of stars — +965 220 56 464 GRAND CINEMAS among them Ed Skrein, Patrick Wilson, Mandy Moore and Nick Jonas ABC ACHRAFIEH 01 209 109 — to tell the epic true story of Midway, the battle that turned the tides 70 415 200 NEW of war. FAMILY FIESTA rounds up the kids’ favourites, including Frozen GRAND GRAND CINEMAS CINEMAS II and Norm of the North 3. -

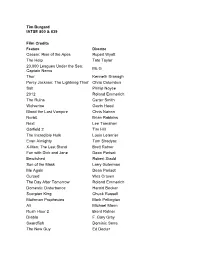

Tim Burgard IATSE 800 & 839 Film Credits Caesar: Rise of the Apes

Tim Burgard IATSE 800 & 839 Film Credits Feature Director Caesar: Rise of the Apes Rupert Wyatt The Help Tate Taylor 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea: Mc G Captain Nemo Thor Kenneth Branagh Percy Jackson: The Lightning Thief Chris Columbus Salt Phillip Noyce 2012 Roland Emmerich The Ruins Carter Smith Wolverine Gavin Hood Blood the Last Vampire Chris Nahon Norbit Brian Robbins Next Lee Tamahori Garfield 2 Tim Hill The Incredible Hulk Louis Leterrier Evan Almighty Tom Shadyac X-Men: The Last Stand Brett Ratner Fun with Dick and Jane Dean Parisot Bewitched Robert Stadd Son of the Mask Larry Guterman Me Again Dean Parisot Cursed Wes Craven The Day After Tomorrow Roland Emmerich Domestic Disturbance Harold Becker Scorpion King Chuck Russell Mothman Prophecies Mark Pellington Ali Michael Mann Rush Hour 2 Brent Ratner Diablo F. Gary Gray Swordfish Dominic Sena The New Guy Ed Decter Pluto Nash Ron Underwood Down and Under David McNally The Patriot Roland Emmerich The Red Planet Anthony Hoffman Mission to Mars Brian dePalma Dungeons & Dragons Cory Solomon Stuart Little Rob Minkoff Inspector Gadget David Kellogg Small Soldiers Joe Dante Supernova Walter Hill 20 Billion Michael Tolkin Mighty Joe Young Ron Underwood Superman Returns John Sheehy Virus John Bruno Batman and Robin Joel Schumacher Chain Reaction Andrew Davis Mars Attacks! Tim Burton The Borrowers Michael McAlister The Phantom Joe Dante Jumanji Joe Johnston Tank Girl Rachel Talalay Cutthroat Island Renny Harlin Terminal Velocity Deran Sarafian Holy Matrimony Leonard Nimoy Stargate Roland -

Midway Production Notes

MIDWAY PRODUCTION NOTES https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/midway For more information, please contact: Meghann Burns Lionsgate 2700 Colorado Avenue Santa Monica, CA 90404 P: 310-255-3999 E: [email protected] MIDWAY LIONSGATE ENTERTAINMENT Official Site: Publicity Materials: http://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/midway/ Facebook: @MidwayMovie Twitter: @MidwayMovie Instagram: @MidwayMovie Hashtag: #MidwayMovie Genre: Action, Drama Rating: PG-13 For sequences of war violence and related images, language and smoking. U.S. Release Date: November 8, 2019 Running Time: 138 minutes Cast: Ed Skrein, Patrick Wilson, Luke Evans, Aaron Eckhart, Nick Jonas, Etsushi Toyokawa, Tadanobu Asano, Luke Kleintank, Jun Kunimura, Darren Criss, Keean Johnson, Alexander Ludwig, with Mandy Moore, Dennis Quaid and Woody Harrelson Directed by: Roland Emmerich Written by: Wes Tooke Produced by: Harald Kloser Credits not contractual SYNOPSIS: MIDWAY centers on the Battle of Midway, a clash between the American fleet and the Imperial Japanese Navy which marked a pivotal turning point in the Pacific Theater during WWII. The film, based on the real-life events of this heroic feat, tells the story of the leaders and sailors who used their instincts, fortitude and bravery to overcome the odds. ONE-LINE: The story of the Battle of Midway, told through the experiences of the WWII leaders and sailors who fought it. 2 MIDWAY “You could ask, how could I fly against these odds, knowing that I probably wasn’t going to come back. Those men were my brothers. I would have flown with them straight into hell. - Dick Best MIDWAY centers on the Battle of Midway, a clash between the American fleet and Imperial Japanese Navy, which marked a turning point in the Pacific Theater during World War II. -

Hollywood and Climate Change

Ecocinema-00-c.qxd 23/7/12 12:00 Page iii ECOCINEMA THEORY AND PRACTICE EDITED BY STEPHEN RUST, SALMA MONANI, AND SEAN CUBITT Ecocinema-00-c.qxd 23/7/12 12:00 Page iv First published 2013 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2013 Taylor & Francis The right of the editors to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Ecocinema theory and practice / edited by Stephen Rust, Salma Monani, and Sean Cubitt. p. cm. — (AFI film readers) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Environmental protection and motion pictures. 2. Environmentalism in motion pictures. 3. Ecology in motion pictures. 4. Documentary films—History and criticism. 5. Motion pictures—United -

Friendship 7 the Epic Orbital Flight of John H

Friendship 7 The Epic Orbital Flight of John H. Glenn, Jr. Other Springer-Praxis books of related interest by Colin Burgess NASA’s Scientist-Astronauts with David J. Shayler 2006 ISBN 978-0-387-21897-7 Animals in Space: From Research Rockets to the Space Shuttle with Chris Dubbs 2007 ISBN 978-0-387-36053-9 The First Soviet Cosmonaut Team: Their Lives, Legacies and Historical Impact with Rex Hall, M.B.E. 2009 ISBN 978-0-387-84823-5 Selecting the Mercury Seven: The Search for America’s First Astronauts 2011 ISBN 978-1-4419-8404-3 Moon Bound: Choosing and Preparing NASA’s Lunar Astronauts 2013 ISBN 978-1-4614-3854-0 Freedom 7: The Historic Flight of Alan B. Shepard, Jr. 2014 ISBN 978-3-3190-1155-4 Liberty Bell 7: The Suborbital Mercury Flight of Virgil I. Grissom 2014 ISBN 978-3-319-04390-6 Colin Burgess Friendship 7 The Epic Orbital Flight of John H. Glenn, Jr. Colin Burgess Bangor , NSW , Australia SPRINGER-PRAXIS BOOKS IN SPACE EXPLORATION Springer Praxis Books ISBN 978-3-319-15653-8 ISBN 978-3-319-15654-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-15654-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015933843 Springer Cham Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2015 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

The Day After Tomorrow Movie

The Day After Tomorrow Movie Name: ____________________________________________Period: _______ Date: ________________ Essential Question: How are we affected by the pollution that we continuously create? Instruction: Write the letter of your answer on the space before each number. ____1. Where does the movie begin? A. Larsen B Ice Shelf, Antarctica B. Larsen B Ice Shelf, Arctic ____2. What are the men doing at the beginning of the movie? A. They are collecting fossilized samples of trees’ annual rings B. They are drilling ice cores out of the glacier. ____3. Why does Jack attempt to go back across the crack? A. To retrieve the core samples. B. To get back home. ____4. What are the scientists measuring in the core samples of ice? A. CO2 and other greenhouse gas levels. B. The severity of global warming in the South Pole. ____5. How does Jack explain the occurrence of an ice age from Global Warming? A. Global Warming will cause the polar ice cap to melt, causing the oceanic currents to shift. The shift in the currents could cause dramatic climate changes, including the onset of another ice age. B. Global Warming will cause the stronger ocean currents, causing polar ice caps to melt. The shift in the currents could cause dramatic climate changes, including the onset of another ice age. ____6. Why don’t the leaders of the conference where Jack presents his data want to make any dramatic changes to reduce emissions? A. It’s too expensive. B. It’s too early to react ____7. How are the temperatures of the ocean currents being monitored? A. -

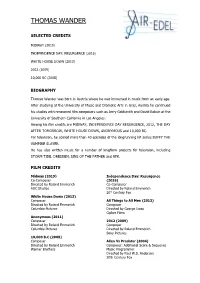

Thomas Wander

THOMAS WANDER SELECTED CREDITS MIDWAY (2019) INDEPENDENCE DAY: RESURGENCE (2016) WHITE HOUSE DOWN (2013) 2012 (2009) 10,000 BC (2008) BIOGRAPHY Thomas Wander was born in Austria where he was immersed in music from an early age. After studying at the University of Music and Dramatic Arts in Graz, Austria he continued his studies with renowned film composers such as Jerry Goldsmith and David Raksin at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Among his film credits are MIDWAY, INDEPENDENCE DAY RESURGENCE, 2012, THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW, WHITE HOUSE DOWN, ANONYMOUS and 10,000 BC. For television, he scored more than 40 episodes of the longrunning hit series BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER. He has also written music for a number of longform projects for television, including STORM TIDE, DRESDEN, SINS OF THE FATHER and RFK. FILM CREDITS Midway (2019) Independence Day: Resurgence Co-Composer (2016) Directed by Roland Emmerich Co-Composer AGC Studios Directed by Roland Emmerich 20th Century Fox White House Down (2013) Composer All Things to All Men (2013) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer Columbia Pictures Directed by George Isaac Cipher Films Anonymous (2011) Composer 2012 (2009) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer Columbia Pictures Directed by Roland Emmerich Sony Pictures 10,000 B.C (2008) Composer Alien Vs Predator (2004) Directed by Roland Emmerich Composer: Additional Score & Sequence Warner Brothers Music Programmer Directed by Paul W.S. Anderson 20th Century Fox The Day After Tomorrow (2004) Hostile Takeover (2001) Co-Composer Composer Directed by Roland Emmerich Directed by Carl Schenkel 20th Century Fox Columbia TriStar The Tunnel (2001) Marlene (2000) Composer Co-Composer Directed by Roland Suso Richter Directed by Joseph Vilsmaier SAT1/Teamworx Senator Film A Handful of Grass (2000) The Venice Project (1999) Composer Composer Directed by Roland Suso Richter Directed by Robert Dornhelm MTM Prod. -

The Day After Tomorrow & Abrupt Climate Change

http://www.foe.co.uk/resource/press_releases/the_day_after_tomorrow_abr_12052004.html Friends of the Earth, Press Release, May 12 2004, slightly adapted The Day After Tomorrow & Abrupt Climate Change The Hollywood film ‘The Day After Tomorrow’ shows apocalyptic scenes supposedly resulting from abrupt climate change. Friends of the Earth’s Director Tony Juniper said: “This is a dramatisation, not a documentary and is above all a Hollywood movie. Although the depiction of the science is exaggerated and at times misleading the scale of the threat and the underlying politics are all too true.” “Science alone has failed to convince politicians and international companies with the power and influence to make a difference. The Day After Tomorrow will reach entirely new audiences who may not have heard about global warming. We hope it will help to create a much needed sense of urgency to fight climate change in the real world, especially in the United States.” Friends of the Earth will now seek to help the public to distinguish between fact and fiction and has today released a briefing on the science of abrupt climate change. 1. What do we know already? Global temperatures rose by an average of about 0.6 °C over the last century and in 2003 there were unusual climate related events worldwide; droughts in Southern Africa, heat waves in India, huge forest fires in Siberia and flooding in parts of South America. Global average temperatures are currently predicted to increase by between 1.4 and 5.8 °C by 2100. The idea that climate change is harmless and will just mean ‘nicer weather’ is wrong and dangerous.