Cultural Imperialism and James Bond's Penis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neues Textdokument (2).Txt

Filmliste Liste de filme DVD Münchhaldenstrasse 10, Postfach 919, 8034 Zürich Tel: 044/ 422 38 33, Fax: 044/ 422 37 93 www.praesens.com, [email protected] Filmnr Original Titel Regie 20001 A TIME TO KILL Joel Schumacher 20002 JUMANJI 20003 LEGENDS OF THE FALL Edward Zwick 20004 MARS ATTACKS! Tim Burton 20005 MAVERICK Richard Donner 20006 OUTBREAK Wolfgang Petersen 20007 BATMAN & ROBIN Joel Schumacher 20008 CONTACT Robert Zemeckis 20009 BODYGUARD Mick Jackson 20010 COP LAND James Mangold 20011 PELICAN BRIEF,THE Alan J.Pakula 20012 KLIENT, DER Joel Schumacher 20013 ADDICTED TO LOVE Griffin Dunne 20014 ARMAGEDDON Michael Bay 20015 SPACE JAM Joe Pytka 20016 CONAIR Simon West 20017 HORSE WHISPERER,THE Robert Redford 20018 LETHAL WEAPON 4 Richard Donner 20019 LION KING 2 20020 ROCKY HORROR PICTURE SHOW Jim Sharman 20021 X‐FILES 20022 GATTACA Andrew Niccol 20023 STARSHIP TROOPERS Paul Verhoeven 20024 YOU'VE GOT MAIL Nora Ephron 20025 NET,THE Irwin Winkler 20026 RED CORNER Jon Avnet 20027 WILD WILD WEST Barry Sonnenfeld 20028 EYES WIDE SHUT Stanley Kubrick 20029 ENEMY OF THE STATE Tony Scott 20030 LIAR,LIAR/Der Dummschwätzer Tom Shadyac 20031 MATRIX Wachowski Brothers 20032 AUF DER FLUCHT Andrew Davis 20033 TRUMAN SHOW, THE Peter Weir 20034 IRON GIANT,THE 20035 OUT OF SIGHT Steven Soderbergh 20036 SOMETHING ABOUT MARY Bobby &Peter Farrelly 20037 TITANIC James Cameron 20038 RUNAWAY BRIDE Garry Marshall 20039 NOTTING HILL Roger Michell 20040 TWISTER Jan DeBont 20041 PATCH ADAMS Tom Shadyac 20042 PLEASANTVILLE Gary Ross 20043 FIGHT CLUB, THE David -

Widescreen Weekend 2007 Brochure

The Widescreen Weekend welcomes all those fans of large format and widescreen films – CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and Imax – and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the best of cinema. HOW THE WEST WAS WON NEW TODD-AO PRINT MAYERLING (70mm) BLACK TIGHTS (70mm) Saturday 17 March THOSE MAGNIFICENT MEN IN THEIR Monday 19 March Sunday 18 March Pictureville Cinema Pictureville Cinema FLYING MACHINES Pictureville Cinema Dir. Terence Young France 1960 130 mins (PG) Dirs. Henry Hathaway, John Ford, George Marshall USA 1962 Dir. Terence Young France/GB 1968 140 mins (PG) Zizi Jeanmaire, Cyd Charisse, Roland Petit, Moira Shearer, 162 mins (U) or How I Flew from London to Paris in 25 hours 11 minutes Omar Sharif, Catherine Deneuve, James Mason, Ava Gardner, Maurice Chevalier Debbie Reynolds, Henry Fonda, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, (70mm) James Robertson Justice, Geneviève Page Carroll Baker, John Wayne, Richard Widmark, George Peppard Sunday 18 March A very rare screening of this 70mm title from 1960. Before Pictureville Cinema It is the last days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The world is going on to direct Bond films (see our UK premiere of the There are westerns and then there are WESTERNS. How the Dir. Ken Annakin GB 1965 133 mins (U) changing, and Archduke Rudolph (Sharif), the young son of new digital print of From Russia with Love), Terence Young West was Won is something very special on the deep curved Stuart Whitman, Sarah Miles, James Fox, Alberto Sordi, Robert Emperor Franz-Josef (Mason) finds himself desperately looking delivered this French ballet film. -

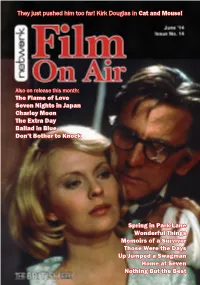

Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! the Flame of Love

They just pushed him too far! Kirk Douglas in Cat and Mouse! Also on release this month: The Flame of Love Seven Nights in Japan Charley Moon The Extra Day Ballad in Blue Don’t Bother to Knock Spring in Park Lane Wonderful Things Memoirs of a Survivor Those Were the Days Up Jumped a Swagman Home at Seven Nothing But the Best Julie Christie stars in an award-winning adaptation of Doris Lessing’s famous dystopian novel. This complex, haunting science-fiction feature is presented in a Set in the exotic surroundings of Russia before the First brand-new transfer from the original film elements in World War, The Flame of Love tells the tragic story of the its as-exhibited theatrical aspect ratio. doomed love between a young Chinese dancing girl and the adjutant to a Russian Grand Duke. One of five British films Set in Britain at an unspecified point in the near- featuring Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong, The future, Memoirs of a Survivor tells the story of ‘D’, a Flame of Love (also known as Hai-Tang) was the star’s first housewife trying to carry on after a cataclysmic war ‘talkie’, made during her stay in London in the early 1930s, that has left society in a state of collapse. Rubbish is when Hollywood’s proscription of love scenes between piled high in the streets among near-derelict buildings Asian and Caucasian actors deprived Wong of leading roles. covered with graffiti; the electricity supply is variable, and water is now collected from a van. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

EDITORIAL Screenwriters James Schamus, Michael France and John Turman CA 90049 (310) 447-2080 Were Thinking Is Unclear

screenwritersmonthly.com | Screenwriter’s Monthly Give ‘em some credit! Johnny Depp's performance as Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl is amazing. As film critic after film critic stumbled over Screenwriter’s Monthly can be found themselves to call his performance everything from "original" to at the following fine locations: "eccentric," they forgot one thing: the screenwriters, Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, who did one heck of a job creating Sparrow on paper first. Sure, some critics mentioned the writers when they declared the film "cliché" and attacked it. Since the previous Walt Disney Los Angeles film based on one of its theme park attractions was the unbear- able The Country Bears, Pirates of the Caribbean is surprisingly Above The Fold 370 N. Fairfax Ave. Los Angeles, CA 90036 entertaining. But let’s face it. This wasn't intended to be serious (323) 935-8525 filmmaking. Not much is anymore in Hollywood. Recently the USA Today ran an article asking, basically, “What’s wrong with Hollywood?” Blockbusters are failing because Above The Fold 1257 3rd St. Promenade Santa Monica, CA attendance is down 3.3% from last year. It’s anyone’s guess why 90401 (310) 393-2690 this is happening, and frankly, it doesn’t matter, because next year the industry will be back in full force with the same schlep of Above The Fold 226 N. Larchmont Blvd. Los Angeles, CA 90004 sequels, comic book heroes and mindless action-adventure (323) 464-NEWS extravaganzas. But maybe if we turn our backs to Hollywood’s fast food service, they will serve us something different. -

Download 007Museum Map

NEWS! at the Bond Museum The aircraft Cessna 172 VIBRA.SE • 17-7019 JAMES BOND 007 James Bond Museum Emmabodavägen 20 Nybro A full-sized Gondola from Venice (apparently just like the one that Roger Moore used in Moonraker). Stockholm MUSEUM Göteborg Växjö Nybro Kalmar Malmö JAMES BOND Emmabodavägen Väg 25 mot Växjö väg Jutarnas MUSEUM EMMABODAVÄGEN 20, 382 45 NYBRO SWEDEN 0 4 81–129 6 0 Västra Förbifarten WWW.007MUSEUM.COM Väg 25 mot Kalmar GPS COORDIN AT ES: N56° 44.416 • E015° 53.462 NYBRO • SWEDEN Golden gun BMW 1200 Cruiser Motorcycle Golden gun pistol SonyTelephones Ericsson P800, K600i BMW motorbike ”The”The Man Man With withThe Golden the Gun” ”Tomorrow Never Dies” Sony Ericsson Golden gun” JamesCinema Bond chair Premierecinema 1 Special designedDesigned glassware glass Casino,Casino Roulette elcome to The World’s only James Bond BondcarsBond cars IanThe Fleming writer the writer Designed007 designed glassware, 007glass Ian Fleming 007 Museum, located in Nybro Sweden. WOver 1,000 square meter. James Bond Collection started in 1965 after Gold- finger by Gunnar Schäfer (change name 2007 to James Bond). The Bond 007 museum is a tribute to Ian Fleming and my missing father Johannes Schäfer, lost since 1959. James Bond 007 Museum started in Nybro Sweden 2002. Book ”Goldfinger”Book ”Goldfinger” GeoffreyGeoffrey Boothroyd Boothroyd and PinballPinball ”Golden ”Golden Eye” Eye” and Ian FlemingsIan Fleming letter letter We have a full-sized Gondola from Venice (apparently just like the one that Roger Moore used in Moonraker). You can see Aston Martin, Airplane Cessna 172, Glastron Boat, BMW Z3, Snowmobile, BMW motorbike, Jaguar E-Type. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

1 Dr. No, 1962 #2 from Russia with Love, 1963

1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess Search Site: Search Follow usus on on Twitter Like usus on on Facebook Lists Top 10s Characters Cast Gadgets Movies Quotes More List of All James Bond Movies The complete list of official James Bond films, made by EON Productions. Beginning with Sean Connery, and going through George Lazenby, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton, Pierce Brosnan and Daniel Craig. Have you ever wondered how many James Bond movies there are? The new film, Spectre, will be released October 2015. #1 Dr. No, 1962 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Honey Ryder Director: Terence Young Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: Dr. No was the first 007 film produced by EON Productions. Bond is sent to Jamaica to investigate the death of MI6 agent John Strangways. He finds his way to Crab Key island, where the mysterious Dr. No awaits. ##22 From Russia With Love, 1963 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Tatiana Romanova Director: Terence Young Running Time: 115 Minutes Synopsis: When MI6 gets a chance to get their hands on a Lektor decoder, Bond is sent to Turkey to seduce the beautiful Tatiana, and bring back the machine. With the help of Kerim Bey, Bond escapes on the Orient Express, but might not make it off alive. hhttttpp::////wwwwww..000077jjaammeess..ccoomm//aarrttiicclleess//lliisstt__ooff__jjaammeess__bboonndd__mmoovviieess..pphhpp 11//44 1111//2277//22001155 LLiissttoof fAAlll lJJaammees sBBoonnd dMMoov viieess #3 Goldfinger, 1964 James Bond: Sean Connery Bond Girl: Pussy Galore Director: Guy Hamilton Running Time: 110 Minutes Synopsis: The Bank of England has detected an unauthorized leakage of gold from the country, and Bond is sent to investigate. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background