Assessment of Harare Water Service Delivery

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Gendered Socio-Economic History of Malawian Women's

“We faced Mabvuto”: A Gendered Socio-economic History of Malawian Women’s Migration and Survival in Harare, 1940 to 1980. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY IREEN MUDEKA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Name of Adviser: Allen F. Isaacman, Name of Co-adviser: Helena Pohlandt McCormick October 2011 © IREEN MUDEKA Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to many friends, colleagues and everyone who provided moral and intellectual support from the period when I started research on this dissertation until its completion. I am very thankful to all Malawian women and men in Rugare, Mufakose, Highfield and Mbare townships of Harare, Zimbabwe and to those in Mpondabwino and Mbayani townships of Zomba and Blantyre who took the time to talk to me about their personal lives. Because of their generosity, they became not just informants but my teachers, mothers, sisters and friends. In Harare, I especially want to thank Mrs. Tavhina Masongera of Rugare for going beyond sharing her life experiences with me to take me under her wing and provide a bridge between me and other women in the townships of Harare as well as of Malawi. Mrs. Masongera took the time to travel with me all the way to Malawi where she introduced me to many women who had lived in Harare during the colonial period. Without her, I would not have known where to begin as a migrant in a country that I was visiting for the very first time. -

Harare Voluntary Local Review of Sustainable Development Goals (Sdgs) Report, June 2020

Harare Voluntary Local Review of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Report, June 2020 1 List of Acronyms AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome CABS Central Africa Building Society COVID-19 Coronavirus disease CMR Child Mortality Rate DM Diabetes Mellitus DPA Distributed Power Africa ECD Early Child Development ECDI Early Child Development Index FBC First Banking Corporation GFF Global Financing Facility HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus HPV Human Papilloma Virus ICDS Inter-Censal Demographic Survey ILO International Labour Organisation IMR Infant Mortality Rate IPRSP Interim Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper IUD Intra-Uterine Devices LFCLS Labour Force and Child Labour Survey OCV Oral Cholera Vaccine M&E Monitoring and Evaluation MICS Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey NEET Not in Employment, Education or Training PGER Primary School Gross Enrolment Ratio. PICES Poverty, Income, Consumption and Expenditure Survey PNER Primary School Net Enrolment Ratio POPs Progestigen Only Pills SDGs Sustainable Development Goals SGER Secondary School Gross Enrolment Ratio. SNER Secondary School Net Enrolment Ratio TB Tuberculosis UNFPA United Nations Population Fund UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund US$ United States Dollar VIAC Visual Inspection with Acetic acid and Cervicography VLR Voluntary Local Review ZIMSTAT Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency ZWL$ Zimbabwe Dollar 2 Profile of Harare Introduction The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) / 2030 Agenda are a universal call for the adoption of measures to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity. National governments alone cannot achieve the ambitious goals of the 2030 Agenda – but cities and regions can contribute to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The City of Harare attaches great importance to implementing the SDGs. -

Risky Sexual Behaviour Among Youths: a Case of Mufakose, Harare

RISKY SEXUAL BEHAVIOUR AMONG YOUTHS: A CASE OF MUFAKOSE, HARARE BY RONALD MUSIZVINGOZA (R077591Y) A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE MASTER OF SCIENCE IN POPULATION STUDIES CENTRE FOR POPULATION STUDIES FACULTY OF SOCIAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF ZIMBABWE 2015 0 DEDICATION To the Glory of the Almighty God, and to my parents who have continued to be a source of inspiration in my life. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank the Almighty God author of my faith in him our hope rest. By the power of the Holy Spirit and his grace I have managed to complete this thesis. To my supervisor Dr N Wekwete, I express my deepest gratitude for her unwavering support, guidance, comments, criticism, and encouragement throughout the duration of this research. I would like to thank my family members for being there for me. Special thanks go to the data collection team Lameck (Doc), Munashe and Callister thank you guys. To S't Peter's Guild Mufakose Anglican Church, thank you very much guys for your prayers, indeed you stood with me in one accord, rambai makadaro vakomana vechita. Infinite thanks to the Centre for Population Studies staff and students, and also to my workmates at the Department of Statistics and Operations Research at NUST who motivated me to finish my studies. To Garikai, you are a star; thank you young man. ii ACRONYMS AIDS Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ASRH Adolescent Sexual Reproductive Health CSW Commercial Sex Workers DALYS Disability Adjusted Life Years EA Enumeration Area FGD -

Pdf Projdoc.Pdf

2011 Annual Report (Celebrations for our 10th anniversary) Contact details: Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Website: www.chiedza.org.zw Face book: type-chiedza child care centre Telephone: 263-4-2922120 or 091 437 698 37 Strachan Street, Ardbennie, Box W142, Waterfalls, Harare, Zimbabwe 1 Foreword Chiedza Child Care Centre was founded in 2001 to care for orphans and vulnerable children in Mbare Suburb of Harare. Over the years Chiedza has steadily grown and developed in size and the range of services that it offers. As at end of December 2011 the Centre was supporting indirectly close to 12,000 children in difficult circumstances providing a wide range of services including early childhood development, education support, psychosocial support, health and nutrition, sports and recreation, livelihoods training and social teaching. The catchment area has expanded to cover Mbare, Sunningdale, Waterfalls, Ardbennie suburbs and Hopely. The development of Chiedza is attributable to the commitment, sterling and selfless effort of the founders and Board members, the donors that have supported Chiedza since its inception and indeed the hard work of the current Board, Director, staff and volunteers. Indeed 2011 was a year of consolidating our experiences and reflecting back to 10 years ago when the organization was established. We enter 2012 with this high moral and enthusiasm to replicate the model to other needy areas. Thank you. Marko Ndlovu Director 2 1. CONTEXT 1.1 2011 Overview Chiedza’s theme for 2011 was “celebrating 10 years of unlocking potential of children in difficult circumstances-building bridges for future leaders”. -

An Investigation Into the Effectiveness of Household Solid Waste Management Strategies in Harare, Zimbabwe

AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE EFFECTIVENESS OF HOUSEHOLD SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES IN HARARE, ZIMBABWE by BENJAMIN MANDEVERE Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the subject ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR S JERIE June 2015 DEDICATION Written and dedicated to my family: Tinashe Prince, Tinevimbo Blessing and Chipo. I also would like to make a special dedication to all the people making a living out of recycling waste in Harare for you are a special kind. i ABSTRACT The main objective of the study was to investigate the effectiveness of the strategies employed by the City of Harare in household solid waste management. To achieve these, structured questionnaires, interviews, observations and focus group discussions were employed in data gathering together with secondary data. The study was conducted in Harare’s low, medium and high density income suburbs. Findings revealed that organic solid waste constituted the largest proportion of waste generated in Harare and other forms are also generated yet their collection is very minimal. Residents resort to illegal night dumping, resulting in the proliferation of associated diseases. In light of these findings, it was recommended that waste collection entities be capacitated, people be educated on waste recycling, reduction and reusing. A commission was to be put in place to ensure proper enforcement of waste legislation, effective and sustainable day in running of household solid waste management in the city. ii KEY TERMS Solid Waste, Household, Management, Strategies, Effectiveness, Harare, Zimbabwe iii STATEMENT OF SUBMISSION I declare that AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE EFFECTIVENESS OF HOUSEHOLD SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES IN HARARE, ZIMBABWE is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. -

Justice and the Urban Poor in Harare, Zimbabwe

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Unisa Institutional Repository JUSTICE AND THE URBAN POOR IN HARARE, ZIMBABWE: AN ETHICAL PERSPECTIVE by RUDOLPH NYAMUDO Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject PHILOSOPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROF. P. MUNGWINI 2020 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................... iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... v Research problem ............................................................................................................................ vi Philosophical paradigm adopted ..................................................................................................... vii Chapter One: Poverty: A Creature of Politics and a Question of Justice. ................................................................1 Chapter Two: Urban Poverty in Harare ................................................................................................................ 18 Chapter Three: Human Dignity and Poverty .......................................................................................................... -

Zimbabwe (Country Code +263) Communication of 12.XII.2018

Zimbabwe (country code +263) Communication of 12.XII.2018: The Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ), Harare, announces updates to the national numbering plan of Zimbabwe. POTRAZ has approved the amendment and consolidation of National Geographical Area Codes on the Public Switched Telephone Network in Zimbabwe by TelOne (Pvt) Limited. POTRAZ has also assigned new subscriber number block of 078 6 XXX XXX and 078 7 XXX XXX to Econet Wireless Zimbabwe. The updated national numbering plan of Zimbabwe is as follows. 1. Definitions Country Code (CC) Country Code (CC) is a digit or a combination of digits (one, two or three) identifying a specific country or countries. Dialling Plan A string or combination of decimal digits, symbols, that defines the method by which the numbering plan is used. A dialling plan includes the use of prefixes, suffixes, and additional information, supplementary to the numbering plan, required to complete the call. Geographic Area Code or Area Code (AC) This refers to an area code that has a defined geographic boundary. Geographic area codes are for conventional fixed- line (or land line) services terminating at fixed points. The Public Switched Telephone Network (PSTN) is divided into several geographic areas. Each of the geographic area is allocated an area code. International Access Prefix (IAP) A digit or combination of digits used to indicate that the number following is an international directory number. In Zimbabwe the International Dialling Access Prefix is ‘00’. National Access Prefix (NAP) or Trunk Prefix A digit or combination of digits used by a calling subscriber to make a call to another subscriber in his own country, but outside his own numbering area or network. -

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004

ZIMBABWE COUNTRY REPORT April 2004 COUNTRY INFORMATION & POLICY UNIT IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM Zimbabwe April 2004 CONTENTS 1 Scope of the Document 1.1 –1.7 2 Geography 2.1 – 2.3 3 Economy 3.1 4 History 4.1 – 4.193 Independence 1980 4.1 - 4.5 Matabeleland Insurgency 1983-87 4.6 - 4.9 Elections 1995 & 1996 4.10 - 4.11 Movement for Democratic Change (MDC) 4.12 - 4.13 Parliamentary Elections, June 2000 4.14 - 4.23 - Background 4.14 - 4.16 - Election Violence & Farm Occupations 4.17 - 4.18 - Election Results 4.19 - 4.23 - Post-election Violence 2000 4.24 - 4.26 - By election results in 2000 4.27 - 4.28 - Marondera West 4.27 - Bikita West 4.28 - Legal challenges to election results in 2000 4.29 Incidents in 2001 4.30 - 4.58 - Bulawayo local elections, September 2001 4.46 - 4.50 - By elections in 2001 4.51 - 4.55 - Bindura 4.51 - Makoni West 4.52 - Chikomba 4.53 - Legal Challenges to election results in 2001 4.54 - 4.56 Incidents in 2002 4.57 - 4.66 - Presidential Election, March 2002 4.67 - 4.79 - Rural elections September 2002 4.80 - 4.86 - By election results in 2002 4.87 - 4.91 Incidents in 2003 4.92 – 4.108 - Mass Action 18-19 March 2003 4.109 – 4.120 - ZCTU strike 23-25 April 4.121 – 4.125 - MDC Mass Action 2-6 June 4.126 – 4.157 - Mayoral and Urban Council elections 30-31 August 4.158 – 4.176 - By elections in 2003 4.177 - 4.183 Incidents in 2004 4.184 – 4.191 By elections in 2004 4.192 – 4.193 5 State Structures 5.1 – 5.98 The Constitution 5.1 - 5.5 Political System: 5.6 - 5.21 - ZANU-PF 5.7 - -

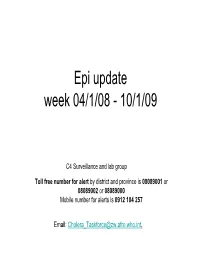

Epi Update Week 04/1/08 - 10/1/09

Epi update week 04/1/08 - 10/1/09 C4 Surveillance and lab group Toll free number for alert by district and province is 08089001 or 08089002 or 08089000 Mobile number for alerts is 0912 104 257 Email: [email protected]. New cholera cases, with case-fatality rates, by week. Zimbabwe, Nov 08 - Jan 09 • * For week 7-13 December, gaps in reporting of data • ** For week 28 December 08- 3 January 09, artefact (Christmas- New Years) 7,000 10.0 9.0 6,000 8.0 5,000 7.0 6.0 4,000 * * 5.0 Cases CFR Cases * CFR 3,000 4.0 3.0 2,000 2.0 1,000 1.0 0 0.0 16-22 Nov 23-29 Nov 30 Nov - 6 Dec 7-13 Dec 14-20 Dec 21-27 Dec 28 Dec-3 Jan 4-10 Jan Global picture The cholera outbreak is not yet under control with 9 of 10 provinces reported cases this week. • Duration of the outbreak: 5 months • To date, cumulative total of 37 806 suspected cases and 1912 deaths have been reported • Number of cases have increased from last week as well as the number of deaths. • CFR increased markedly this week to 6 % similar to the week preceding the Christmas and New year’s holiday, • and CFR still much higher than expected for a cholera outbreak (normally <1%). • This week (4 Jan -10 Jan 2009), 656 cases per day reported and 39 persons are dying every day of cholera. • This week (4 Jan -10 Jan 2009) nearly half of the deaths (41%) are occurring outside treatments centre →unavailability of health care (especially human resources shortage) “Hot spots” this week • Mashonaland West (increase cases and CFRs > 5% and high attack rates and 1/3 of the total weekly number of cases) • Midlands, (increase cases and CFRs > 5% and high attack rates) • Manicaland (CFRs > 5% and high attack rates) • Mathebeleland South (increase cases) • Chitungwiza (CFRs > 5%) • Masvingo (CFRs > 5%) • Mashonaland central (increase cases) Cumulative cholera cases, with cumulative case-fatality rates. -

Coordinating Education Transitional Services for Adolescent Orphan Girls in Zimbabwe a Community Systems Framework

WORKING PAPER 1 JUNE 2012 GLOBAL SCHOLARS PROGRAM WORKING PAPER SERIES Coordinating Education Transitional Services for Adolescent Orphan Girls in Zimbabwe A Community Systems Framework Pamhidzayi Berejena Mhongera GLOBAL SCHOLARS Pamhidzayi Berejena Mhongera is a guest scholar PROGRAM WORKING of the Center for Universal Education at Brookings. PAPER SERIES This working paper series focuses on edu- cation policies and programs in developing countries, featuring research conducted by guest scholars at the Center for Universal Education at Brookings. CUE develops and disseminates effective solutions to the chal- lenges of achieving universal quality educa- tion. Through the Global Scholars Program, guest scholars from developing countries join CUE for six months to pursue research on global education issues. We are delight- ed to share their work through this series. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This paper is dedicated to the orphans, vulnerable children and youth of the Blossoms Children Com- munity (BCC) and Youth in Transition Trust Zimbabwe (YITTZ) of Mufakose, Harare and to all the children in various institutions across Zimbabwe. It has been a great experience watching these children blossom for the last seven years and having the opportunity of sharing their joys and sorrows, their hopes and dreams. As they make the transition to adulthood, it is my greatest desire to see them having positive live- lihood outcomes, breaking the cycle of poverty and marginalization. I appreciate the loving support of my husband, Mus- tafa, whose encouragement has made it possible for me to pursue my dreams. I am grateful to my children, Rutendo, Daudi, Mtuwa and Mutsa, for their patience and the joy they bring in my life. -

GOVERNMENTGAZETTE Or One and a Half Spacing Betweenthelines

ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published byAuthority Vol. XC, No. 67 30th NOVEMBER, 2012 Price US$2,00 General Notice 514 of 2012. Income Tax Bill, 2012 (H.B. 5, 2012). STATE PROCUREMENT BOARD A.M. ZVOMA Tenders Invited 30-11-2012. Clerk of Parliament. TENDERS must be enclosed in sealed envelopes, endorsed on the outside with the General Notice 517 of 2012. advertised tender number, description, closing date and must be posted in time to be STATE PROCUREMENT BOARD sorted into Post Office Box Number CY 408, Causeway, or delivered by handto the Principal Officer, State Procurement Board, Fifth Floor, Old Reserve Bank Building, Samora Machel Avenue, Harare, before 10.00 a.m. on the closing date. Tenders Invited C. NYANHETE. 30-11-2012. Principal Offices, State Procurement Board. TENDERS must be enclosed in sealed envelopes, endorsed on the outside with the - Tender number advertised tender number,description, closing date and must be postedin time to be sorted into Post Office Box Number CY 408, Causeway, or delivered by hand to the ZETDC/15/2012. Supply and delivery of weed killer. Principal Officer, State Procurement Board, Fifth Floor, Old Reserve Bank Building, Samora Machel Avenue, Harare, before 10.00 a.m. on the closing date. ZETDC/16/2012. Supply and delivery of battery banks. C. NYANHETE, Bidding documents for the above-mentioned tenders can be 30-11-2012. Principal Officer, State Procurement Board. inspected andare obtainable upon paymentofanon-refundable fee of US$10,00, payable by cash only from the Procurement Tender number Administrator, Procurement Office, Offices 223 and 227, ZETDC Head Office, Second Floor, Electricity Centre, 25, RDS.27 of 2012. -

Nutrition ATLAS Zimbabwe

Nutrition ATLAS Zimbabwe ∼ Who is doing What Where in Nutrition (2005 - 2006) VOLUME II ∼ June, 2006 For every child Health, Education, Equality, Protection ADVANCE HUMANITY Nutrition ATLAS Zimbabwe Preface Child Survival and development remain principal objectives if we are to realize and achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), and in doing so leave a legacy for which our children will thank us. Nutrition and maternal health are fundamental to achieving these goals. Every year, it is estimated that undernutrition contributes to the deaths of 5.6 million children, worldwide, under the age of five. When nutrition falls short, damage is done to individuals and to society. When pregnant women are not adequately nourished, their babies are born at low weights, putting their survival at risk. When girls are undernourished, their future ability to bear healthy children is threatened. Unfortunately, Zimbabwe is not immune to the challenges of malnutrition, where HIV/AIDS and an economic crisis have combined to the detriment of children’s nutritional status. This Nutrition Intervention Atlas, developed by UNICEF in consultation with the Nutrition Technical Consultative Group and other stakeholders, provides an overview of the types of interventions that are being carried out in the field of nutrition and the implementing organisations in Zimbabwe during 2005-2006 The Atlas will serve as a planning tool for UNICEF and stakeholders to make further inroads toward Zimbabwe’s realization of the MDGs. Within the context of the Nutrition Technical Consultative Group, this Atlas will be disseminated bi-annually in order to improve planning and implementation of nutrition programs in Zimbabwe.