Participatory Policy Development for the Lowland Rainfed Rice-Based Farming Systems Towards Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Evaluation of the Emergence of Nueva Ecija As the Rice Granary of the Philippines

Presented at the DLSU Research Congress 2015 De La Salle University, Manila, Philippines March 2-4, 2015 A Historical Evaluation of The Emergence of Nueva Ecija as the Rice Granary of the Philippines Fernando A. Santiago, Jr., Ph.D. Department of History De La Salle University [email protected] Abstract: The recognition of Nueva Ecija’s potential as a seedbed for rice in the latter half of the nineteenth century led to the massive conversion of public land and the establishment of agricultural estates in the province. The emergence of these estates signalled the arrival of wide scale commercial agriculture that revolved around wet- rice cultivation. By the 1920s, Nueva Ecija had become the “Rice Granary of the Philippines,” which has been the identity of the province ever since. This study is an assessment of the emergence of Nueva Ecija as the leading rice producer of the country. It also tackles various facets of the rice industry, the profitability of the crop and some issues that arose from rice being a controlled commodity. While circumstances might suggest that the rice producers would have enjoyed tremendous prosperity, it was not the case for the rice trade was in the hands of middlemen and regulated by the government. The government policy which favored the urban consumers over rice producers brought meager profits, which led to disappointment to all classes and ultimately caused social tension in the province. The study therefore also explains the conditions that made Nueva Ecija the hotbed of unrest prior to the Second World War. Historical methodology was applied in the conduct of the study. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

(0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines

ORIS Project (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines Joni T. Acay and Nikki Dyanne C. Realubit In cooperation with: Page | 0 ORIS Project CLP PROJECT ID (0399912) Establishing Baseline Data for the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole, Philippines PROJECT LOCATION AND DURATION: Luzon Island, Philippines Provinces of Bataan, Quirino, Isabela and Cagayan August 2012-July 2014 PROJECT PARTNERS: ∗ Mabuwaya Foundation Inc., Cabagan, Isabela ∗ Department of Natural Sciences (DNS) and Department of Development Communication and Languages (DDCL), College of Development Communication and Arts & Sciences, ISABELA STATE UNIVERSITY-Cabagan, ∗ Wild Bird Club of the Philippines (WBCP), Manila ∗ Community Environmental and Natural Resources Office (CENRO) Aparri, CENRO Alcala, Provincial Enviroment and Natural Resources Office (PENRO) Cagayan ∗ Protected Area Superintendent (PASu) Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, CENRO Naguilian, PENRO Isabela ∗ PASu Quirino Protected Landscape, PENRO Quirino ∗ PASu Mariveles Watershed Forest Reserve, PENRO Bataan ∗ Municipalities of Baggao, Gonzaga, San Mariano, Diffun, Limay and Mariveles PROJECT AIM: Generate baseline information for the conservation of the Critically Endangered Isabela Oriole. PROJECT TEAM: Joni Acay, Nikki Dyanne Realubit, Jerwin Baquiran, Machael Acob Volunteers: Vanessa Balacanao, Othniel Cammagay, Reymond Guttierez PROJECT ADDRESS: Mabuwaya Foundation, Inc. Office, CCVPED Building, ISU-Cabagan Campus, -

LUZON, P.I., 1941 FINAL OPERATIONS on LUZON 34 3 February - 20 July 1945 BABUYAN CHANNEL CAPE ENGANO ELEVATIONS in FEET 0 1500 3000 OVER

A B C D LUZON, P.I., 1941 FINAL OPERATIONS ON LUZON 34 3 February - 20 July 1945 BABUYAN CHANNEL CAPE ENGANO ELEVATIONS IN FEET 0 1500 3000 OVER 0 20 40 60 80 100 Aparri 1 N 1 HISTORY DEPARTMENT 23 June . USMA SCALE OF MILES Frank Martini R Gunzaga Lauag n a y a g a Batac C xx 26 June Guer. xx Guer. 25 June LUZON STRAIGHT Bangued Tuguegarrao Vigan Operations against the Shobu Force were among the most Lubuagan xx 37 difficult during the war. Yamashita’s forces kept several xx divisions and guerrilla forces occupied right up to the end of Candon Guer. 19 June PALANAN BAY Bontoc 10 July Ilagan the war. His group was compressed into the area shown by 1 July where it no longer could affect MacArthur’s use of . R 20 July t a Luzon as a base. g Luna xx a xx xxx 6 M Guer. SHOBU Curdon San Fernando 20 Mar. 2 Bagabag 2 xx 10 June Bauang xx 32 Salano 33 Baguio LINGAYEN xx GULF 37 Damortis Rosario Pazorrubio Balete Pass Dagupan Tayug Lingoyen 3 Feb. San Carlos Urdaneto 4 Feb. Aguilar xxx BALER BAY San Jose 12 Feb. I Rizal Paniqui xx Camiling Griswold’s XIV Corps penetrated the Shimbu Line Guimba Bongabon 6 Licab (5 Feb. line shown), using three divisions. On 15 . Sangitan R Tarlac Cababatuan March, Hall’s XI Corps assumed control of the sector g By 20 February, the XIV and XI O’Donnell n 11 Feb. and constituted operations against the Shimbu Group. -

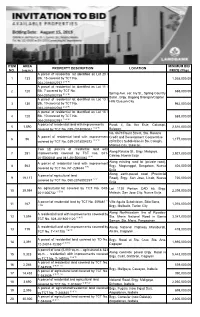

ITEM NO. AREA (Sq.M.) PROPERTY DESCRIPTION LOCATION

ITEM AREA MINIMUM BID PROPERTY DESCRIPTION LOCATION NO. (sq.m.) PRICE (Php) A parcel of residential lot identified as Lot 20 / 1 133 Blk. 15 covered by TCT No. 1,038,000.00 004-2016002757 2/ 4/ 8/ A parcel of residential lot identified as Lot 11 / 2 120 Blk. 7 covered by TCT No. 888,000.00 Spring Ave. cor. Ivy St., Spring Country 004-2016002759 2/ 4/ 8/ Subd., Brgy. Bagong Silangan/Capitol A parcel of residential lot identified as Lot 13 / Hills Quezon City 3 130 Blk. 10 covered by TCT No. 962,000.00 004-2016002760 2/ 4/ 8/ A parcel of residential lot identified as Lot 15 / 4 120 Blk. 10 covered by TCT No. 888,000.00 004-2016002761 2/ 4/ 8/ A parcel of residential land with improvements Purok 4, Bo. Iba Este, Calumpit, 5 1,890 2,816,000.00 covered by TCT No. 039-2018006042 1/ 4/ 7/ Bulacan No. 0679 Pount Street, Sto. Rosario A parcel of residential land with improvement Credit and Development Cooperative 6 96 1,177,000.00 covered by TCT No. 039-2018004372 1/ 4/ 7/ (SRCDC) Subdivision in Bo. Caingin, Malolos City, Bulacan Two (2) parcels of residential land with Along Relucio St., Brgy. Maligaya, 7 291 improvements covered by TCT nos. 041- 3,927,000.00 Cabiao, Nueva Ecija 2015000041 and 041-2015000042 1/ 4/ Along existing road lot (private road), A parcel of residential land with improvement 8 563 Brgy. Magtanggol, Bongabon, Nueva 404,000.00 covered by TCT No. NT-224644 1/ 5/ Ecija Along earth-paved road (Provincial A parcel of agricultural land 9 19,117 Road), Brgy. -

Occs and Bccs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1

List of OCCs and BCCs with Microsoft Office 365 Accounts1 COURT/STATION ACCOUNT TYPE EMAIL ADDRESS RTC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Caloocan City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Las Pinas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Makati City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Malabon City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Mandaluyong City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Manila City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Marikina City OCC [email protected] 1 to search for a court or email address, just click CTRL + F and key in your search word/s RTC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Muntinlupa City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Navotas City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Paranaque City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasay City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] METC OCC Pasig City OCC [email protected] RTC OCC Quezon City OCC [email protected] METC OCC -

Sector C Agricultural and Fishery Water Management

Sector C Agricultural and Fishery Water Management Sector C. Agricultural and Fishery Water Management Table of Contents Pages C.1 Present Conditions of Agricultural and Fishery .................................................................. C-1 C.1.1 Characteristics of Agriculture and Fishery in the Study Area ............................... C-1 C.1.1.1 Agriculture ................................................................................................. C-1 C.1.1.2 Fishery ....................................................................................................... C-2 C.1.1.3 Irrigation Development in the Study Area ................................................. C-3 C.1.1.4 Projected Future Irrigation Projects ........................................................... C-5 C.1.2 Estimated Water Demand for Agriculture and Fishery ......................................... C-7 C.1.2.1 Irrigation Water Demand ........................................................................... C-7 C.1.2.2 Other Water Demands ...............................................................................C-11 C.1.3 Water Charge related to Irrigation ....................................................................... C-12 C.1.3.1 Irrigation Service Fee (ISF) ..................................................................... C-12 C.1.3.2 Collection Ratio of ISF ............................................................................ C-12 C.2 Problems and Issues of Agriculture/Irrigation and Fishery Sector on IWRM Plan -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 I I I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The owing explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Concernedjudges

TO THE CONCERNEDJUDGES ON THE SUBJECT FOCUS GROUP DISCUSSION (FGD) LOWER CASE CARRYING CAPACITY OF COURT JUDGES ON OCTOBER 30, 2013 AT HOTEL GRA CELANE, MCARTHUR HIGHWAY, FERNANDO, SAN AGUST1N, CITY OF SAN PAMPANGA The Supreme Cou/'t; with the assistance of the United States Agency .for International Development (USAID), thru the Asia Foundation, is conducting a study of the case carrying capacity of Lower Court judges. This study will enable the Supreme Court to assess the needs of courts and judges based on judicial workloads and case complexities by establishing a reasonable caseload for them. The establishment of the reasonable caseload will provide a rational basis for the determination of: (1) how many courts and judge positions are needed in order to ensure efficiency and timeliness of court operations and outputs; (2) where courts are needed; (3) how many cases judges should be expected to handle annually; and (4) establish timeliness for different types of cases In connection therewith, the following judges are hereby authorized to attend the said focus group discussion on OFFICIAL TIMEIOFFICIAL BUSINESS, chargeable to local funds, if authorized and available, provided their court calendars are properly managed and the parties notified in advance of any cancelled.hearing: NAME ~ --STATION 1. Hou. Efren B. Tienzo (APJ) 2. Hon. LucinaA. Dayaon RTC Branch 54, Macabebe, Pampanga RTC, Branch 20, Malolos City 3. Hon. Mirasol Ong Dychingco 4. Hen. Josefina D. Farrales RTC, Branch 69, Iba, Zambales 5. Hen. Basilio R. Gabo, Jr. IIRTC, Branch 11, Malolos City r 6. Hon. Felizardo S. Montero, Jr. RTC, Branch 29, Cabanatuan City. -

Rice Area Mapping, Yield, and Production Forecast for the Province of Nueva Ecija Using RADARSAT Imagery

Can. J. Remote Sensing, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 1Á16, 2011 Rice area mapping, yield, and production forecast for the province of Nueva Ecija using RADARSAT imagery C. Chen, E.J.P. Quilang, E.D. Alosnos and J. Finnigan Abstract. Monitoring rice production is an important tool for the Government of the Philippines’ objective to achieve rice sufficiency by 2013. For decision makers to ensure that the country has an adequate rice supply, it is imperative that timely and accurate information on rice area, yield forecasts, and production be regularly updated with little or no statistical response burden to producers; this study describes a process well suited for the integration and utilization of the methodologies for rice monitoring using radar data. Currently, the national and regional rice production in the Philippines is estimated through a complex and labor-intensive process using surveys of farmers and fields. Faster, reliable, and more efficient methods are needed to monitor production because rice production is affected by seasonal crop prices, climate, and daily weather. To accurately forecast rice production in near real time, remote sensing technology was used. A rice crop monitoring application using RADARSAT imagery was initially developed and tested in 2001. This application was modified and retested in the wet season of 2007 in Mun˜oz and Santo Domingo, Nueva Ecija, Philippines. This application demonstrated the capability to forecast rice production over an extended region. The program also offered flexibility in its ancillary data requirements, making it suitable for a practical and operational rice monitoring program. During the wet season of 2008, the rice area in the province of Nueva Ecija was mapped, and yield and production were forecast using the developed methodology. -

The Case of Selected Communities in Talugtug, Nueva Ecija, Philippines

The CGPRT Centre The Regional Co-ordination Centre for Research and Development of Coarse Grains, Pulses, Roots and Tuber Crops in the Humid Tropics of Asia and the Pacific (CGPRT Centre) was established in 1981 as a subsidiary body of UN/ESCAP. Objectives In co-operation with ESCAP member countries, the Centre will initiate and promote research, training and dissemination of information on socio-economic and related aspects of CGPRT crops in Asia and the Pacific. In its activities, the Centre aims to serve the needs of institutions concerned with planning, research, extension and development in relation to CGPRT crop production, marketing and use. Programmes In pursuit of its objectives, the Centre has two interlinked programmes to be carried out in the spirit of technical cooperation among developing countries: 1. Research and development which entails the preparation and implementation of projects and studies covering production, utilization and trade of CGPRT crops in the countries of Asia and the South Pacific. 2. Human resource development and collection, processing and dissemination of relevant information for use by researchers, policy makers and extension workers. CGPRT Centre Working Papers currently available: Working Paper No. 58 Food Security Strategies for Vanuatu by Shadrack R. Welegtabit Working Paper No. 59 Integrated Report: Food Security Strategies for Selected South Pacific Island Countries by Pantjar Simatupang and Euan Fleming Working Paper No. 60 CGPRT Crops in the Philippines: A Statistical Profile 1990-1999 by Mohammad A.T. Chowdhury and Muhamad Arif Working Paper No. 61 Stabilization of Upland Agriculture under El Nino Induced Climatic Risk: Impact Assessment and Mitigation Measures in Malaysia by Ariffin bin Tawang, Tengku Ariff bin Tengku Ahmad and Mohd. -

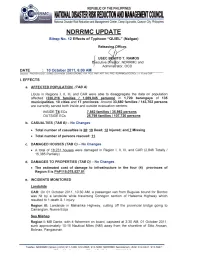

NDRRMC Update SND Sitrep No 12 Re TY QUIEL 10 Oct 2011

Region II: One (1) service motor banca and one (1) cargo/passenger vessel, both bound bound for Maconacon and Divilacan, Isabela, moored at San Vicente Fish Port, Sta. Ana, Cagayan Three (3) service motor bancas and one (1) cargo/passenger motor banca with a total of 20 passengers bound to Camiguin Island were left stranded as they moored at Veteranz Wharf Aparri, Cagayan Region III: Missing Fishermen on board F/Bs Princess Angela and Queen Lorena 2: • Four (4) out of eight (8) fishermen believed to be from F/b Princess Angela were rescued: one (1) was pronounced dead on arrival at the hospital, two (2) died while afloat in the middle of the sea while the remaining two (2) allegedly went out of their minds and untied themselves from the floating containers and have been missing since then; SAR operations are ongoing • Four (4) out of 9 fishermen from F/b Queen Lorena 2 were rescued on 05 October while SAR Operations is still ongoing for the missing The reported missing F/banca Brando Ice with 14 fishermen on board returned home safely on 05 October 2011. Said banca took shelter at the vicinity of Cabra Island, Mindoro during the height of the typhoon Vehicular Accident Region I: Nick Basto, 6 years old from Brgy. San Julian Central, Agoo, La Union suffered a cerebral concussion after being hit by a tricycle while crossing the street from the evacuation center to buy food. He was brought to La Union Medical Center for medical attention Storm Surge Region I: A storm surge occurred in Barangays Tabuculan, Pasungol, and Bucalag of Santa, Ilocos Sur on 01 October 2011.