Issue 2 Summer 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Huddersfield & District Association Football League

Huddersfield & District Association Football League Saturday, February 26 West Riding FA Challenge Cup Round 4 Bay Athletic v Uppermill Huddersfield FA Junior Challenge Cup Round 3 Uppermill Res v Netherton Res Barlow Cup Round 2 Lepton Highlanders v Britannia Sports Shepley v Moldgreen Groom Cup Round 2 New Mill 94 v Linthwaite Athletic AFC Lindley v Y.M.C.A. Richardson Cup Round 2 Honley Res v Cumberworth Res Heywood Irish Centre Res v Upperthong Res Shelley Res v Slaithwaite Utd Res Gee Cup Round 2 Kirkheaton Rovers ‘A’ v AFC Lindley Res Division 1 Diggle v Netherton Meltham Athletic v Hepworth Utd Cumberworth v Berry Brow Division 2 Honley v Heywood Irish Centre FC Kirkheaton Rovers v Westend Scholes v Royal Dolphins Skelmanthorpe v Scissett Wooldale Wanderers v Slaithwaite Utd Division 3 Brook Motors v Savile Town Dalton Crusaders v KKS Sun Inn Grange Moor v Heyside H.V.Academicals v Paddock Rangers Upperthong SC v Shelley Division 4 AFC Black Horse v Flockton Fenay Bridge FC v Hade Edge Holmfirth Town v Cartworth Moor Moldgreen Con v Spotted Cow Mount v AFC Waterloo Reserve Division 1 Berry Brow Res v Meltham Athletic Res Britannia Sports Res v Diggle Res Kirkheaton Rovers Res v Shepley Res Westend Res v Newsome Res Reserve Division 2 Diggle A v Wooldale Wanderers Res Mount Res v Scholes Res Netherton 'A' v Uppermill 'A' Reserve Division 3 Cartworth Moor Res v Berry Brow 'A' Cumberworth 'A' v Holmbridge Res Hade Edge Res v Brook Motors Res KKS Sun Inn Res v Honley 'A' Meltham Athletic 'A' v H.V.Academicals Res P a g e | 1 www.hdafl.org.uk -

Huddersfield Area

48 (Section 52) ADVERTISEMENTS. ~ Telt>phone• lti!JT ~ Telephone /liff" H U D DE ltS FIELD 971 HUDDERSFIELD 971 482 482 WM. ARNOLD & SON, e1\RTER & eo .• CENTRAL SALT DEPu'J'","' BIRKHOUSE BOILFR WORKS, 39, Market Street, and Water Street, Haddersfield, ~addoeR, Jiuddersfield. Manufacturers and Merchants of firewood and Firelighters. Cement Plaster Whiting, Granite, Lime-stone, Slag, Spar, 8and, French Chalk, La'ths, Naiis, Hair, Colors, Oils, Paints, Putty, Varnishes, Brushes, MAKERS OF ALL KINDS OF BOILERS. Blachlng Brass Polishes, Turpentine, Glue, Salt, Saltpetre. Soap, Soda. Charcoai. Chloride of Lime, Ammonia, Liquid Annatto, Vinegar, Corks, REPAIRS PROMPTLY ATTENDED TO. Fibrous Plaster, Centre Flowers, and Trusses, &.c. "& Telephone /liiiT Tel. : Huddersfield 131. Telegrams : Station Tel. : Huddersfield 131a. "TROHAB DARWIN, HUDDEB&FIKLD.' 41y HUDDERSFIELD 41y -L. CONTRACTOR FOR CABS DAY OR NIGHT. lB' HIS MAJESTY'S MAILS ~ ~ { <tonfecttoner Wedding & Funeral Carriages, Olass·Sided & Plain Hearses. JQ t~a V er, ant~ <taterer. Also tbe latest designs in New Silent= Tyred Funeral Cars. ti4, New .Street, Huddersfield. funerals turntsbeb <tomplete. WEDDING CAKES of artistic design and highest THOMAS DARWIN, quality, from 10f6. LIVERY STABLES, DECORATIVE CAKES in great variety. Fartown, HUDDERSFIELD ~ Telephone w 17X Machine and Metal Bl'oke,.!l .C. • 17x BRIG HOUSE and Commission Agent. :\.1) V * LISTER BROOK & CO., Boiler and Pipe Coverer ~ $ Telephone: with Non-eonclueting ~· J.._ HUDDERSFIELD 792. Builders & Contractors, Composition. ~ :El B. :I: G-~ 0 U S E, V ~ And at l'i•:I.R\'. Estimates r'. Sectional Covering a Speciality. Dealers InSanitary Pipes, Chimney Pots, Fire Brlclis. Fire Clay. Lime, Cement, &c. Free. ""-V Same..price as " Plastic." IIRDUitO MORTAR FOR SALE. -

Berry Brow Infant and Nursery School Birch Road, Berry Brow, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD4 7LP

School report Berry Brow Infant and Nursery School Birch Road, Berry Brow, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD4 7LP Inspection dates 7–8 December 2016 Overall effectiveness Good Effectiveness of leadership and management Good Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Good Personal development, behaviour and welfare Good Outcomes for pupils Good Early years provision Good Overall effectiveness at previous inspection Requires improvement Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school Together leaders and governors have tackled The headteacher and staff have created a safe the issues from the last inspection. and caring school community where each pupil Consequently, teaching and outcomes have is valued. improved and are now good. Relationships between staff and pupils are Provision in the early years has improved so strong and contribute to pupils’ good that the proportion of children securing a good behaviour. Pupils say that they feel safe and level of development has risen. The teaching of well cared for. phonics in the early years and key stage 1 has Care and support for vulnerable pupils through improved to good. the use of a weekly nurture group is good. Attainment at the end of Year 2 is broadly Leaders are clear about their roles and average. From their different starting points responsibilities across the school. They have an this represents good progress, particularly in accurate view of the school’s strengths and reading. However, pupils’ progress in writing is weaknesses. a little variable because some school policies are not followed consistently. Additionally, The use of the pupil premium funding has been some staff do not always demonstrate a secure enhanced and staff are clear about which understanding of spelling, punctuation and pupils should be benefiting from this additional grammar when teaching writing. -

Huddersfield (Town Centre and University) to Holmfirth (Town Centre)

Holmfirth Transitional Town Proposed Cycle Route – Huddersfield (town centre and university) to Holmfirth (town centre). The proposal seeks to create, as far as possible, an off road cycle path between the town centres of Huddersfield and Holmfirth, together with link paths from other significant Holme Valley settlements, notably Honley, Brockholes, Netherthong, New Mill and Wooldale. In addition to these settlements there are a number of other significant workplace and school destinations linked to or on the proposed route, notably Thongsbridge, Armitage Bridge, Lockwood, Folly Hall, Kirklees College, and Honley and Holmfirth High Schools Where an off road path is not considered to be achievable, the proposed route utilises the road network, with appropriate amendments and improvements to create a safe cycling environment. The existing and proposed routes are described below in clearly identifiable sections. Existing routes include some off road paths which are usable and used currently for cycling, and which will become part of the complete route, subject to any necessary improvements. Where off road paths connect to the road network, and for on road elements of the route, improvements to create a safe cycling environment are proposed. The route sections 1. Huddersfield town centre, within the ring road 2. Ring Road to Lockwood 3. Lockwood to Berry Brow 4. Berry Brow to Honley 5. Honley to Thongsbridge 6. Thongsbridge to Holmfirth 1. Huddersfield town centre – within the ring road The town centre is generally regarded as a relatively safe cycling environment. Traffic levels have been reduced by the introduction of bus gates, and speeds are relatively low. Some cycling infrastructure has been provided and there are some signed routes and safe ring road crossings, however provision is piecemeal and further improvements are required. -

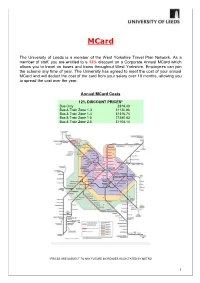

Mcard Application

MCard The University of Leeds is a member of the West Yorkshire Travel Plan Network. As a member of staff, you are entitled to a 12% discount on a Corporate Annual MCard which allows you to travel on buses and trains throughout West Yorkshire. Employees can join the scheme any time of year. The University has agreed to meet the cost of your annual MCard and will deduct the cost of the card from your salary over 10 months, allowing you to spread the cost over the year. Annual MCard Costs 12% DISCOUNT PRICES * Bus Only £818.40 Bus & Train Zone 1-3 £1120.86 Bus & Train Zone 1-4 £ 1316.74 Bus & Train Zone 1-5 £ 1580.83 Bus & Train Zone 2-5 £1104.14 *PRICES ARE SUBJECT TO ANY FUTURE INCREASES AS DICTATED BY METRO 1 As a first step, you will need to order your Corporate Annual MCard on the MCard website www.m-card.co.uk. Please also complete the attached deduction application and return a hard copy to the Staff Benefits Team, 11.11 E.C. Stoner Building. Please retain a copy of the Terms and Conditions. Corporate Annual MCard Terms and Conditions The purpose of this Scheme is to provide discounted payment terms for staff. The University is not involved, nor liable, for the delivery of WYCA services. Staff have a separate contract with WYCA for delivery of their services. WYCA’s terms relating to the use of their MCard are available at https://m-card.co.uk/terms-of-use/annual-mcard-terms- conditions/ A Bus-Only MCard is valid on virtually all the services of all bus operators within West Yorkshire. -

Huddersfield Area

234 When CaiiJng gi,·e Name of Exchange as we/lilt{ Numlit!l'l HUDDERSFIELD AREA, Including ARMITAGE BRIDGE, BAILIFF BRIDGE, BRIG HOUSE, BERRY BROW, BROCKHOLES, CLAYTON WEST, DENBY DALE, DOBCROSS, ELLAND, EMLEY MOOR, FENAV BRIDGE, GOLCAR, GREETLAND, HOLVWELL GREEN, HOLMBRIDGE, HOLMFIRTH, HUDDERSFIELD, HONLEY, KIRKHEATON, KIRKBURTON, KINGSTONE, LONGWOOD, LEPTON, LINTHWAITE, MARSDEN, MELT HAM, MILNSBRIDGE, MYTHOLM-BRIDGE.. NORTON THORPE, NETHERTON, NETHERTHONG, NEW MILL, QUARMBY, RASTRICK, SLAITHWAITE, SKELMANTHORPE, SCHOLES, SHELLY, STAINLAND, SHEPLEY, SCISSETT, THONGSBRIDGE and WEST VALE. (For ELLAND, GREETLAND, STAINLAND and WEST VALE Subscribers, see also HALIFAX.) Offices uf ~uhsnibers marked with an a,;tcrisk can he used as Call Ofliccs. NAME OF EXCHANGE:, HUDDERSFIELD. Hwlrkr~;field 0790 ALLEN B. Prior ......... ''liolmcliffe," l\Iountjoy r.I 1I u,],]er,;fiehl 537 ARMITAGE & Nortun ......................John William st ll uthkrstielcl 280 ASPINALL A. IV.," Labnrnam Villa,'' Newsome rd l I w hJer,fidd 0763 ASTLEY AlfrNI, Steam .Joinery IVks, Mar.,h llolmfirth ... 48 BARKER & Moot!.'·, IVoolkn l\lanufrs, Dobroyd mill :'\ l' wIll ill Milnshrith;e 22 BARLOW Ellis Ltd ............. Jianufg- Birl'ill·ncliife t'hc1nists, JJrp;a]tc>rs II w Iclersticlti 586 BEAU MONT .Jmm·,; ............ Farri<:r, 101 King· st If onley ..... 32 BEAU MONT .T. & Co., Wonlh·n l\1anfs, Steps mill llnddersfiehl 583 BEAUMONT,Joshua&Co. ,Wulnl\Infs, Wood street ~[p]tham ... 046 BEAU MONT ~amud ..................... Brow mills Hwlrkrsfielrl 579 BEEGLING Daniel Henry ... Surgeon, :! Belgr:we tPr II wl<lcrsfil'ld 584 BENTLEY F. IV .......... Stockbroker, Heinw"'".l I I u,],]prstie lrl 0810 BINNS .John & Co.,Hope,Twinc l\fnfs, 10 Kirkgak Bri~1nm~c· 74 BOOTH I.ister ........ -

Collections Guide 2 Nonconformist Registers

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 2 NONCONFORMIST REGISTERS Contacting Us What does ‘nonconformist’ mean? We recommend that you contact us to A nonconformist is a member of a religious organisation that does not ‘conform’ to the Church of England. People who disagreed with the book a place before visiting our beliefs and practices of the Church of England were also sometimes searchrooms. called ‘dissenters’. The terms incorporates both Protestants (Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, Congregationalists, Quakers WYAS Bradford etc.) and Roman Catholics. By 1851, a quarter of the English Margaret McMillan Tower population were nonconformists. Prince’s Way Bradford How will I know if my ancestors were nonconformists? BD1 1NN Telephone +44 (0)113 393 9785 It is not always easy to know whether a family was Nonconformist. The e. [email protected] 1754 Marriage Act ordered that only marriages which took place in the Church of England were legal. The two exceptions were the marriages WYAS Calderdale of Jews and Quakers. Most people, including nonconformists, were Central Library therefore married in their parish church. However, nonconformists often Northgate House kept their own records of births or baptisms, and burials. Northgate Halifax Some people were only members of a nonconformist congregation for HX1 1UN a short time, in which case only a few entries would be ‘missing’ from Telephone +44 (0)1422 392636 the Anglican parish registers. Others switched allegiance between e. [email protected] different nonconformist denominations. In both cases this can make it more difficult to recognise them as nonconformists. WYAS Kirklees Central Library Where can I find nonconformist registers? Princess Alexandra Walk Huddersfield West Yorkshire Archive Service holds registers from more than a HD1 2SU thousand nonconformist chapels. -

West Riding Yorkshire

WEST RIDING YORKSHIRE. HUDDERSFIELD • • Hampson Ruth Ann (Mrs.), butcher, 26 Manchester street Hawkyard Edward, stationer~ news agent, Lockwood Hanley & Brierley,coal mers.Railwa.y station, Fitzwilliam st Hawkyard Henry, tailor, Manchester road. Hanley Catherine ( Mn.), clothes dealer, 59 Kirkgate HawkyardJ as.commercial traveller,Meltham rd. Lo~kwood Hanley Thomas, rug manufacturer, <1: Dundas street Ha.wkyard John, Woodman, Primrose hill, RilShcliffe Hannan John, !rla?.ier, 5 Fitzwilliam street Hawkyard Mary (Mrs.), confectioner, 10 Northgate Hanson, Dale & Co. ma.nufa.cturer3 of block tin tubes, lead Hayley Henry (exors. of), manufacturing chemist, Brick & composition pipes for water, gll.!l & soil pipes of all sizes bank, N orth~ate up to 6 in. also window leads for crown & plate glass, lead Headey Robert Ada:n11, news agent, 104 Upperhead row weights for Jacquard looms, & metallic wire for florists, of Headey Robert Lee, news agent 5 Victoria lane, King st all sizes from No. 7 to 20; & dealers in pig lead & ingot Heap John & Brothers, woollen manufacturers, 32 Westgate tin, Colne road. See advertisement Heap R. R. &. A. woollen manufrs. 26 Market st.; 4-l. Ex- Hanson Alien, beer retailer, Crosland moor chang~; & at Cartworth, Holmfirth Hanson Alien, shopkeeper, Salford, Lockwood Heap Frederick, lilhopkeeper, Victoria street, Mold green Hanson Benj. woollen manufactr. see Hirst, Hanson & Sons Heap George, woollen manufacturer, 28 Vance's buildingq Hanson Benj. Byram, woollen manfr;~ee Hirst, Hanson & Sons HeapJohnWilliam,woollen mercht.3Brook's yard, Market! t Ha.nson Brook, farmer, Hanson lane, Lockwood Heap Williarn, commercial traveller, 8 Luck lane, Marsh Hanson George Henry, grocer, Paddock Heaps T. -

WEST YORKSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society a Photograph Exists for Milestones Listed Below but Would Benefit from Updating!

WEST YORKSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society A photograph exists for milestones listed below but would benefit from updating! National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position YW_ADBL01 SE 0600 4933 A6034 ADDINGHAM Silsden Rd, S of Addingham above EP149, just below small single storey barn at bus stop nr entrance to Cringles Park Home YW_ADBL02 SE 0494 4830 A6034 SILSDEN Bolton Rd; N of Silsden Estate YW_ADBL03 SE 0455 4680 A6034 SILSDEN Bolton Rd; Silsden just below 7% steep hill sign YW_ADBL04 SE 0388 4538 A6034 SILSDEN Keighley Rd; S of Silsden on pavement, 100m south of town sign YW_BAIK03 SE 0811 5010 B6160 ADDINGHAM Addingham opp. Bark La in narrow verge, under hedge on brow of hill in wall by Princefield Nurseries opp St Michaels YW_BFHA04 SE 1310 2905 A6036 SHELF Carr House Rd;Buttershaw Church YW_BFHA05 SE 1195 2795 A6036 BRIGHOUSE Halifax Rd, just north of jct with A644 at Stone Chair on pavement at little layby, just before 30 sign YW_BFHA06 SE 1145 2650 A6036 NORTHOWRAM Bradford Rd, Northowram in very high stone wall behind LP39 YW_BFHG01 SE 1708 3434 A658 BRADFORD Otley Rd; nr Peel Park, opp. Cliffe Rd nr bus stop, on bend in Rd YW_BFHG02 SE 1815 3519 A658 BRADFORD Harrogate Rd, nr Silwood Drive on verge opp parade of shops Harrogate Rd; north of Park Rd, nr wall round playing YW_BFHG03 SE 1889 3650 A658 BRADFORD field near bus stop & pedestrian controlled crossing YW_BFHG06 SE 212 403 B6152 RAWDON Harrogate Rd, Rawdon about 200m NE of Stone Trough Inn Victoria Avenue; TI north of tunnel -

Collections Guide 2 Nonconformist Registers

COLLECTIONS GUIDE 2 NONCONFORMIST REGISTERS Contacting Us What does ‘nonconformist’ mean? Please contact us to book a place A nonconformist is a member of a religious organisation that does not ‘conform’ to the Church of England. People who disagreed with the before visiting our searchrooms. beliefs and practices of the Church of England were also sometimes called ‘dissenters’. The terms incorporates both Protestants (Baptists, WYAS Bradford Methodists, Presbyterians, Independents, Congregationalists, Quakers Margaret McMillan Tower etc.) and Roman Catholics. By 1851, a quarter of the English Prince’s Way population were nonconformists. Bradford BD1 1NN How will I know if my ancestors were nonconformists? Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0152 e. [email protected] It is not always easy to know whether a family was Nonconformist. The 1754 Marriage Act ordered that only marriages which took place in the WYAS Calderdale Church of England were legal. The two exceptions were the marriages Central Library & Archives of Jews and Quakers. Most people, including nonconformists, were Square Road therefore married in their parish church. However, nonconformists often Halifax kept their own records of births or baptisms, and burials. HX1 1QG Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0151 Some people were only members of a nonconformist congregation for e. [email protected] a short time, in which case only a few entries would be ‘missing’ from the Anglican parish registers. Others switched allegiance between WYAS Kirklees different nonconformist denominations. In both cases this can make it Central Library more difficult to recognise them as nonconformists. Princess Alexandra Walk Huddersfield Where can I find nonconformist registers? HD1 2SU Telephone +44 (0)113 535 0150 West Yorkshire Archive Service holds registers from more than a e. -

To Download a Map and Directions to Brooke's Mill

LOCAL MAP th u o S B d M a irc o e h R lt R e h o m a ad o m s w R e o N a d Berry Brow e itag Ro rm ad A B6 110 Armitage Bridge e ad n Ro a w L Vie e t rn o ou o B k F e an riv B 6 D 1 ten 6 ar M A d a Lane H o rk Pa ne a R La w d oor k M r a o e y h d H d N a B o e n t a h e o g d n e i i r R k t s W n o er g n on R M lc o S o a t o F a o r d n R e o R a o d ad North Light Brookes Mill • Armitage Bridge • Huddersfield West Yorkshire • United Kingdom • HD4 7NR Tel +44 (0) 1484 340000 www.northlightyorkshire.co.uk HUDDERSFIELD MAP North Light Brookes Mill • Armitage Bridge • Huddersfield West Yorkshire • United Kingdom • HD4 7NR Tel +44 (0) 1484 340000 www.northlightyorkshire.co.uk DIRECTIONS From the M62 East bound – Junction 24 Take the A629 to Huddersfield Town Centre ring road. Turn right onto the ring road and stay in the middle lane through one set of lights. As you follow the ring road round the three lanes split off into two lanes each and you need to be in the middle set at the next lights sign-posted Holmfirth/Sheffield A616. -

Liverpool, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield

Hellifield Lancaster Carlisle Lancaster Carlisle Darlington Scarborough Starbeck Knaresborough Liverpool Leeds Gargrave Ilkley Poulton-le-Fylde Skipton Cattal Hammerton Poppleton Ben Rhydding York Cononley Harrogate Manchester Sheffield Burley-in-Wharfedale Layton Steeton & Silsden Hornbeam Park Otley Principal services are shown as thick lines Clitheroe Kirkham & Keighley Menston Guiseley Pannal Wesham Salwick Local services are shown as thin lines North Limited services are shown as open lines Crossflatts Ulleskelf Whalley Baildon Weeton Blackpool The pattern of services shown is based on the standard Bingley South Mondays to Fridays timetable. At weekends certain Church Fenton stations are closed and some services altered. Langho Saltaire Horsforth Moss Side Airport interchange Shipley St Annes- Ramsgreave & Wilpshire Colne Headingley Blackpool on-the-Sea Pleasure Lytham Preston Tram/Metro Interchange Frizinghall Beach tle Burley Park Southport is Squires Ansdell & w Sherburn-in-Elmet dt Gate Fairhaven al Forster Square New Cross East Selby Gilberdyke sw Nelson Pudsey Bramley Gates Garforth Garforth Micklefield Wressle Howden Eastrington on O Bradford Lostock ht & Hall Bamber is ch Interchange Bridge Pleasington Cherry Tree Mill Hill Blackburn R r on hu gt Meols Cop C rin South Birkdale cc t Leyland A oa Cottingley Leeds Milford nc Brierfield Hull u n H to ve Bescar Lane ap ro Morley Saltmarshe Euxton H G Burnley Central Darwen se Hillside Balshaw Ro Castleford Lane New Lane Halifax Goole Burnley Barracks Woodlesford GlasshoughtonPontefract