Jamie Aron Final Ja

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus

Bauhaus 1 Bauhaus Staatliches Bauhaus, commonly known simply as Bauhaus, was a school in Germany that combined crafts and the fine arts, and was famous for the approach to design that it publicized and taught. It operated from 1919 to 1933. At that time the German term Bauhaus, literally "house of construction" stood for "School of Building". The Bauhaus school was founded by Walter Gropius in Weimar. In spite of its name, and the fact that its founder was an architect, the Bauhaus did not have an architecture department during the first years of its existence. Nonetheless it was founded with the idea of creating a The Bauhaus Dessau 'total' work of art in which all arts, including architecture would eventually be brought together. The Bauhaus style became one of the most influential currents in Modernist architecture and modern design.[1] The Bauhaus had a profound influence upon subsequent developments in art, architecture, graphic design, interior design, industrial design, and typography. The school existed in three German cities (Weimar from 1919 to 1925, Dessau from 1925 to 1932 and Berlin from 1932 to 1933), under three different architect-directors: Walter Gropius from 1919 to 1928, 1921/2, Walter Gropius's Expressionist Hannes Meyer from 1928 to 1930 and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe Monument to the March Dead from 1930 until 1933, when the school was closed by its own leadership under pressure from the Nazi regime. The changes of venue and leadership resulted in a constant shifting of focus, technique, instructors, and politics. For instance: the pottery shop was discontinued when the school moved from Weimar to Dessau, even though it had been an important revenue source; when Mies van der Rohe took over the school in 1930, he transformed it into a private school, and would not allow any supporters of Hannes Meyer to attend it. -

The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 5-30-1986 The design and construction of furniture for mass production Kevin Stark Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Stark, Kevin, "The design and construction of furniture for mass production" (1986). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ROCHESTER INSTITUTE OP TECHNOLOGY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The College of Fine and Applied Arts in Candidacy for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS The Design and Construction of Furniture for Mass Production By Kevin J. Stark May, 1986 APPROVALS Adviser: Mr. William Keyser/ William Keyser Date: 7 I Associate Adviser: Mr. Douglas Sigler/ Date: Douglas Sigler Associate Adviser: Mr. Craig McArt/ Craig McArt Date: U3{)/8:£ ----~-~~~~7~~------------- Special Assistant to the h I Dean for Graduate Affairs:Mr. Phillip Bornarth/ P i ip Bornarth Da t e : t ;{ ~fft, :..:..=.....:......::....:.:..-=-=-=...i~:...::....:..:.=-=..:..:..!..._------!..... ___ -------7~'tf~~---------- Dean, College of Fine & Applied Arts: Dr. Robert H. Johnston/ Robert H. Johnston Ph.D. Date: ------------------------------ I, Kevin J. Stark , hereby grant permission to the Wallace Memorial Library of RIT, to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Date : ____5__ ?_O_-=B::;..... 0.:.......-_____ CONTENTS Thesis Proposal i CHAPTER I - Introduction 1 CHAPTER II - An Investigation Into The Design and Construction Process Side Chair 2 Executive Desk 12 Conference Table 18 Shelving Unit 25 CHAPTER III - A Perspective On Techniques Used In Industrial Furniture Design Wood 33 Metals 37 Plastics 41 CHAPTER IV - Conclusion 47 CHAPTER V - Footnotes 49 CHAPTER VI - Bibliography 50 ILLUSTRATIONS Page I. -

Working Checklist 00

Taking a Thread for a Walk The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 21, 2019 - June 01, 2020 WORKING CHECKLIST 00 - Introduction ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Untitled from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 17 3/4 × 13 3/4" (45.1 × 34.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 74 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Study for Nylon Rug from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 20 5/8 × 15 1/8" (52.4 × 38.4 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 75 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) With Verticals from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 19 3/8 × 14 1/4" (49.2 × 36.2 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation in memory of Joseph Fearer Weber/Danilowitz 73 Wall, framed. Located next to projection in elevator bank ANNI ALBERS (American, born Germany. 1899–1994) Orchestra III from Connections 1983 One from a portfolio of nine screenprints composition: 26 5/8 × 18 7/8" (67.6 × 47.9 cm); sheet: 27 3/8 × 19 1/2" (69.5 × 49.5 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

Questions of Fashion

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/677870 . Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Bard Graduate Center are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to West 86th. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 185.16.163.10 on Tue, 23 Jun 2015 06:24:53 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Questions of Fashion Lilly Reich Introduction by Robin Schuldenfrei Translated by Annika Fisher This article, titled “Modefragen,” was originally published in Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, 1922. 102 West 86th V 21 N 1 This content downloaded from 185.16.163.10 on Tue, 23 Jun 2015 06:24:53 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Introduction In “Questions of Fashion,” Lilly Reich (1885–1947) introduces readers of the journal Die Form to recent developments in the design of clothing with respect to problems of the age.1 Reich, who had her own long-established atelier in Berlin, succinctly contextualizes issues that were already mainstays for the Werkbund, the prominent alliance of designers, businessmen, and government figures committed to raising design standards in Germany, of which she was a member. -

E in M Ag Azin Vo N

Ein Magazin von T L 1 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, im Jahr 2019 feiert Deutschland 100 Jahre Bauhaus und wir fast vier Jahrzehnte TEcnoLuMEn. 140 Jahre Tradition – eine Vergan - genheit voller Geschichten, die wir Ihnen erzählen wollen. Die Wagenfeld-Leuchte ist ohne Eine davon beginnt 1919 in Weimar. Zweifel eine dieser zeitlosen Walter Gropius gründete das Designikonen und seit fast 40 Jahren Staatliche Bauhaus, eine Schule, is t sie ganz sicher das bekannteste in der Kunst und Handwerk Werkstück unseres Hauses. auf einzigartige Weise zusammen - Das ist unsere Geschichte. geführt wurden. Interdisziplinär, Weshalb TEcnoLuMEn autorisierter weltoffen und experimentierfreudig. Hersteller dieser Leuchte ist, wer ob Architektur, Möbel, Foto- das Bremer unternehmen gegründet grafie, Silberwaren – Meister und hat, welche Designleuchten wir Studierende des Bauhaus schufen neben diesem und anderen Klassi - viele Klassiker. kern außerdem im Sortiment haben und welche Philosophie wir bei TEcnoLuMEn verfolgen, all das möchten wir Ihnen auf den folgen - den Seiten unseres Magazins erzählen. Weil Zukunft Vergangenes und Gegenwärtiges braucht. und das Heute ohne Geschichten nicht möglich ist. Wir freuen uns sehr, Ihnen die erste Ausgabe unseres TEcnoLuMEn Magazins TL1 vorstellen zu können 4 und wünschen Ihnen eine interes - Die Idee des Bauhaus sante und erkenntnisreiche Lektüre. 6 Die TEcnoLuMEn Geschichte carsten Hotzan 8 Interview mit Walter Schnepel Geschäftsführer 12 Alles Handarbeit 14 Designikone im Licht der Kunst 16 „Junge Designer“ r e n g e i l F m i h c a o J Die von Wilhelm Wagenfeld 1924 entworfene und im Staatlichen Bauhaus Weimar hergestellte Metallversion der „Bauhaus-Leuchte“. Herbert Bayer „Eine solche Resonanz kann man nicht Max Bill Laszlo Moholy-nagy mit organisation erreichen und nicht mit Propaganda. -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

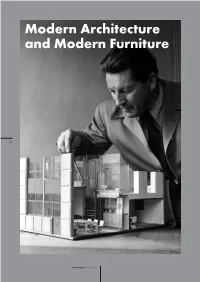

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture

Modern Architecture and Modern Furniture 14 docomomo 46 — 2012/1 docomomo46.indd 14 25/07/12 11:13 odern architecture and Modern furniture originated almost during the same period of time. Modern architects needed furniture compatible with their architecture and because Mit was not available on the market, architects had to design it themselves. This does not only apply for the period between 1920 and 1940, as other ambitious architectures had tried be- fore to present their buildings as a unit both on the inside and on the outside. For example one can think of projects by Berlage, Gaudí, Mackintosh or Horta or the architectures of Czech Cubism and the Amsterdam School. This phenomenon originated in the 19th century and the furniture designs were usually developed for the architect’s own building designs and later offered to the broader consumer market, sometimes through specialized companies. This is the reason for which an agree- ment between the architect and the commissioner was needed, something which was not always taken for granted. By Otakar M á c ˆe l he museum of Czech Cubism has its headquarters designed to fit in the interior, but a previous epitome of De in the Villa Bauer in Liboˇrice, a building designed Stijl principles that culminated in the Schröderhuis. Tby the leading Cubist architect Jiˆrí Gocˆár between The chair was there before the architecture, which 1912 and 1914. In this period Gocˆár also designed Cub- was not so surprising because Rietveld was an interior ist furniture. Currently the museum exhibits the furniture designer. The same can be said about the “father” of from this period, which is not actually from the Villa Bauer Modern functional design, Marcel Breuer. -

Anni Albers Large Print Guide

ANNI ALBERS 11 October 2018 – 27 January 2018 LARGE PRINT GUIDE Please return to the holder CONTENTS Room 1 ................................................................................3 Room 2 ................................................................................9 Room 3 ..............................................................................34 Room 4 ..............................................................................49 Room 5 ..............................................................................60 Room 6 ..............................................................................70 Room 7 ..............................................................................90 Room 8 ..............................................................................96 Room 9 ............................................................................ 109 Room 10 .......................................................................... 150 Room 11 .......................................................................... 183 2 ROOM 1 3 INTRODUCTION Anni Albers (1899–1994) was among the leading innovators of twentieth-century modernist abstraction, committed to uniting the ancient craft of weaving with the language of modern art. As an artist, designer, teacher and writer, she transformed the way weaving could be understood as a medium for art, design and architecture. Albers was introduced to hand-weaving at the Bauhaus, a radical art school in Weimar, Germany. Throughout her career Albers explored the possibilities -

Design Earth and Judith Raum Exhibit at Bauhaus Dessau

Bauhaus Dessau Design Earth and Judith Raum exhibit at Bauhaus Dessau Press release After a long Covid-19 break, the Bauhaus Dessau Foundation opens two exhibition projects in the context of the annual theme "Infrastructure" on Thursday, 24 June 2021: In the Intermezzo Design Earth. Climate Inher- itance at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau, the Design Earth team shows ten UNESCO World Heritage Sites as figures in the climate crisis. And under the title Textile territories, artist Judith Raum explores Otti Berger's textile works in her installations at the Bauhaus Museum Dessau and in the Bauhaus P r e s s c o n t a c t Building. Ute König P +49-340-6508-225 E x h i b i t i o n s [email protected] Bauhaus Dessau Foundation Design Earth. Climate Inheritance Gropiusallee 38 Intermezzo 06846 Dessau-Roßlau >> Bauhaus Museum Dessau Germany bauhaus-dessau.de 24 June – 3 Oct 2021 facebooK.com/bauhausdessau twitter.com/gropiusallee Corona has brought global tourism and its infrastructures to a near standstill. What has emerged is a moment that gives space for reflection: on ways to deal with the collective responsibility of inheriting a planet in climate crisis. El Dessau-Roßlau, Hadi Jazairy and Rania Ghosn of Design Earth look at ten UNESCO World 22 June 2021 Heritage Sites as figures in the climate crisis and try to concretely locate the abstract of climate change in these iconic places. The case studies show a broad spectrum of climate impacts: from rising sea levels to species extinc- tion and melting glaciers. -

Langues, Accents, Prénoms & Noms De Famille

Les Secrets de la Septième Mer LLaanngguueess,, aacccceennttss,, pprréénnoommss && nnoommss ddee ffaammiillllee Il y a dans les Secrets de la Septième Mer une grande quantité de langues et encore plus d’accents. Paru dans divers supplément et sur le site d’AEG (pour les accents avaloniens), je vous les regroupe ici en une aide de jeu complète. D’ailleurs, à mon avis, il convient de les traiter à part des avantages, car ces langues peuvent être apprises après la création du personnage en dépensant des XP contrairement aux autres avantages. TTaabbllee ddeess mmaattiièèrreess Les différentes langues 3 Yilan-baraji 5 Les langues antiques 3 Les langues du Cathay 5 Théan 3 Han hua 5 Acragan 3 Khimal 5 Alto-Oguz 3 Koryo 6 Cymrique 3 Lanna 6 Haut Eisenör 3 Tashil 6 Teodoran 3 Tiakhar 6 Vieux Fidheli 3 Xian Bei 6 Les langues de Théah 4 Les langues de l’Archipel de Minuit 6 Avalonien 4 Erego 6 Castillian 4 Kanu 6 Eisenör 4 My’ar’pa 6 Montaginois 4 Taran 6 Ussuran 4 Urub 6 Vendelar 4 Les langues des autres continents 6 Vodacci 4 Les langages et codes secrets des différentes Les langues orphelines ussuranes 4 organisations de Théah 7 Fidheli 4 Alphabet des Croix Noires 7 Kosar 4 Assertions 7 Les langues de l’Empire du Croissant 5 Lieux 7 Aldiz-baraji 5 Heures 7 Atlar-baraji 5 Ponctuation et modificateurs 7 Jadur-baraji 5 Le code des pierres 7 Kurta-baraji 5 Le langage des paupières 7 Ruzgar-baraji 5 Le langage des “i“ 8 Tikaret-baraji 5 Le code de la Rose 8 Tikat-baraji 5 Le code 8 Tirala-baraji 5 Les Poignées de mains 8 1 Langues, accents, noms -

Anni Albers and Lilly Reich in Barcelona 1929: Weavings and Exhibition Spaces

Laura Martínez de Guerenu˜ https://doi.org/10.3986/wocrea/1/momowo1.14 Anni Albers and Lilly Reich This paper examines the work of Anni Albers (1899–1994) to ascertain the impact that the visit to Barcelona International Exhibition during the summer of 1929 had on her later work. Albers was in Barcelona 1929: then a student of the Bauhaus weaving workshop and would graduate the following semester, in February 1930.1 Lilly Reich (1885–1947) would not join the Bauhaus until 1932.2 However, Reich’s Weavings and Exhibition Spaces work in the interior designs of the vast German exhibits in Barcelona 1929 is echoed in a building that was collectively designed by the various Bauhaus workshops under the directorship of Hannes Meyer (1889–1954), and in which Albers participated, also in 1929. Despite all that has been discussed in relation to the Barcelona International Exhibition, an important fact has remained undiscovered for scholarship in the fields of decorative arts, design history and material culture. In early 1929 the Bauhaus had already acquired many commitments to participate in several exhibitions throughout that year.3 Barcelona, together with Basel, Brussels, Leningrad The Bauhaus participated as an industry in the German section of the 1929 Barce- lona International Exhibition, sending objects to the Palaces of Textile Industries and Paris, was one of the many cities outside Germany, where the Bauhaus was planning to display and Decorative and Industrial Arts, two interiors (besides another thirteen) de- its objects. In fact, the Bauhaus participated as an industry in the German section of the 1929 signed by Lilly Reich and Mies van der Rohe. -

B Au H Au S Im a G Inis Ta E X H Ib Itio N G U Ide Bauhaus Imaginista

bauhaus imaginista bauhaus imaginista Exhibition Guide Corresponding p. 13 With C4 C1 C2 A D1 B5 B4 B2 112 C3 D3 B4 119 D4 D2 B1 B3 B D5 A C Walter Gropius, The Bauhaus (1919–1933) Bauhaus Manifesto, 1919 p. 24 p. 16 D B Kala Bhavan Shin Kenchiku Kōgei Gakuin p. 29 (School of New Architecture and Design), Tokyo, 1932–1939 p. 19 Learning p. 35 From M3 N M2 A N M3 B1 B2 M2 M1 E2 E3 L C E1 D1 C1 K2 K K L1 D3 F C2 D4 K5 K1 G D1 K5 G D2 D2 K3 G1 K4 G1 D5 I K5 H J G1 D6 A H Paul Klee, Maria Martinez: Ceramics Teppich, 1927 p. 57 p. 38 I B Navajo Film Themselves The Bauhaus p. 58 and the Premodern p. 41 J Paulo Tavares, Des-Habitat / C Revista Habitat (1950–1954) Anni and Josef Albers p. 59 in the Americas p. 43 K Lina Bo Bardi D and Pedagogy Fiber Art p. 60 p. 45 L E Ivan Serpa From Moscow to Mexico City: and Grupo Frente Lena Bergner p. 65 and Hannes Meyer p. 50 M Decolonizing Culture: F The Casablanca School Reading p. 66 Sibyl Moholy-Nagy p. 53 N Kader Attia G The Body’s Legacies: Marguerite Wildenhain The Objects and Pond Farm p. 54 Colonial Melancholia p. 70 Moving p. 71 Away H G H F1 I B J C F A E D2 D1 D4 D3 D3 A F Marcel Breuer, Alice Creischer, ein bauhaus-film.