NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Nat Immunol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

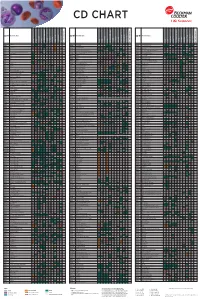

Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse

Welcome to More Choice CD Marker Handbook For more information, please visit: Human bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/humancdmarkers Mouse bdbiosciences.com/eu/go/mousecdmarkers Human and Mouse CD Marker Handbook Human and Mouse CD Marker Key Markers - Human Key Markers - Mouse CD3 CD3 CD (cluster of differentiation) molecules are cell surface markers T Cell CD4 CD4 useful for the identification and characterization of leukocytes. The CD CD8 CD8 nomenclature was developed and is maintained through the HLDA (Human Leukocyte Differentiation Antigens) workshop started in 1982. CD45R/B220 CD19 CD19 The goal is to provide standardization of monoclonal antibodies to B Cell CD20 CD22 (B cell activation marker) human antigens across laboratories. To characterize or “workshop” the antibodies, multiple laboratories carry out blind analyses of antibodies. These results independently validate antibody specificity. CD11c CD11c Dendritic Cell CD123 CD123 While the CD nomenclature has been developed for use with human antigens, it is applied to corresponding mouse antigens as well as antigens from other species. However, the mouse and other species NK Cell CD56 CD335 (NKp46) antibodies are not tested by HLDA. Human CD markers were reviewed by the HLDA. New CD markers Stem Cell/ CD34 CD34 were established at the HLDA9 meeting held in Barcelona in 2010. For Precursor hematopoetic stem cell only hematopoetic stem cell only additional information and CD markers please visit www.hcdm.org. Macrophage/ CD14 CD11b/ Mac-1 Monocyte CD33 Ly-71 (F4/80) CD66b Granulocyte CD66b Gr-1/Ly6G Ly6C CD41 CD41 CD61 (Integrin b3) CD61 Platelet CD9 CD62 CD62P (activated platelets) CD235a CD235a Erythrocyte Ter-119 CD146 MECA-32 CD106 CD146 Endothelial Cell CD31 CD62E (activated endothelial cells) Epithelial Cell CD236 CD326 (EPCAM1) For Research Use Only. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Flow Reagents Single Color Antibodies CD Chart

CD CHART CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name CD N° Alternative Name Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone Beckman Coulter Clone T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells T Cells B Cells Granulocytes NK Cells Macrophages/Monocytes Platelets Erythrocytes Stem Cells Dendritic Cells Endothelial Cells Epithelial Cells CD1a T6, R4, HTA1 Act p n n p n n S l CD99 MIC2 gene product, E2 p p p CD223 LAG-3 (Lymphocyte activation gene 3) Act n Act p n CD1b R1 Act p n n p n n S CD99R restricted CD99 p p CD224 GGT (γ-glutamyl transferase) p p p p p p CD1c R7, M241 Act S n n p n n S l CD100 SEMA4D (semaphorin 4D) p Low p p p n n CD225 Leu13, interferon induced transmembrane protein 1 (IFITM1). p p p p p CD1d R3 Act S n n Low n n S Intest CD101 V7, P126 Act n p n p n n p CD226 DNAM-1, PTA-1 Act n Act Act Act n p n CD1e R2 n n n n S CD102 ICAM-2 (intercellular adhesion molecule-2) p p n p Folli p CD227 MUC1, mucin 1, episialin, PUM, PEM, EMA, DF3, H23 Act p CD2 T11; Tp50; sheep red blood cell (SRBC) receptor; LFA-2 p S n p n n l CD103 HML-1 (human mucosal lymphocytes antigen 1), integrin aE chain S n n n n n n n l CD228 Melanotransferrin (MT), p97 p p CD3 T3, CD3 complex p n n n n n n n n n l CD104 integrin b4 chain; TSP-1180 n n n n n n n p p CD229 Ly9, T-lymphocyte surface antigen p p n p n -

Mouse CD302/CLEC13A Antibody Antigen Affinity-Purified Polyclonal Sheep Igg Catalog Number: AF6424

Mouse CD302/CLEC13A Antibody Antigen Affinity-purified Polyclonal Sheep IgG Catalog Number: AF6424 DESCRIPTION Species Reactivity Mouse Specificity Detects mouse CD302/CLEC13A in direct ELISAs and Western blots. In direct ELISAs, approximately 30% crossreactivity with recombinant human CD302 is observed. Source Polyclonal Sheep IgG Purification Antigen Affinitypurified Immunogen Mouse myeloma cell line NS0derived recombinant mouse CD302/CLEC13A Asp21His165 Accession # Q9DCG2 Formulation Lyophilized from a 0.2 μm filtered solution in PBS with Trehalose. See Certificate of Analysis for details. *Small pack size (SP) is supplied either lyophilized or as a 0.2 μm filtered solution in PBS. APPLICATIONS Please Note: Optimal dilutions should be determined by each laboratory for each application. General Protocols are available in the Technical Information section on our website. Recommended Sample Concentration Western Blot 1 µg/mL See Below DATA Western Blot Detection of Mouse CD302/CLEC13A by Western Blot. Western blot shows lysates of mouse spleen tissue. PVDF Membrane was probed with 1 µg/mL of Mouse CD302/CLEC13A Antigen Affinitypurified Polyclonal Antibody (Catalog # AF6424) followed by HRPconjugated AntiSheep IgG Secondary Antibody (Catalog # HAF016). A specific band was detected for CD302/CLEC13A at approximately 32 kDa (as indicated). This experiment was conducted under reducing conditions and using Immunoblot Buffer Group 8. PREPARATION AND STORAGE Reconstitution Sterile PBS to a final concentration of 0.2 mg/mL. Shipping The product is shipped at ambient temperature. Upon receipt, store it immediately at the temperature recommended below. *Small pack size (SP) is shipped with polar packs. Upon receipt, store it immediately at 20 to 70 °C Stability & Storage Use a manual defrost freezer and avoid repeated freezethaw cycles. -

Human Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to Find Them

biomolecules Review Human Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to Review HumanFind Them Lectins, Their Carbohydrate Affinities and Where to FindCláudia ThemD. Raposo 1,*, André B. Canelas 2 and M. Teresa Barros 1 1, 2 1 Cláudia D. Raposo * , Andr1 é LAQVB. Canelas‐Requimte,and Department M. Teresa of Chemistry, Barros NOVA School of Science and Technology, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa, 2829‐516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 12 GlanbiaLAQV-Requimte,‐AgriChemWhey, Department Lisheen of Chemistry, Mine, Killoran, NOVA Moyne, School E41 of ScienceR622 Co. and Tipperary, Technology, Ireland; canelas‐ [email protected] NOVA de Lisboa, 2829-516 Caparica, Portugal; [email protected] 2* Correspondence:Glanbia-AgriChemWhey, [email protected]; Lisheen Mine, Tel.: Killoran, +351‐212948550 Moyne, E41 R622 Tipperary, Ireland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-212948550 Abstract: Lectins are a class of proteins responsible for several biological roles such as cell‐cell in‐ Abstract:teractions,Lectins signaling are pathways, a class of and proteins several responsible innate immune for several responses biological against roles pathogens. such as Since cell-cell lec‐ interactions,tins are able signalingto bind to pathways, carbohydrates, and several they can innate be a immuneviable target responses for targeted against drug pathogens. delivery Since sys‐ lectinstems. In are fact, able several to bind lectins to carbohydrates, were approved they by canFood be and a viable Drug targetAdministration for targeted for drugthat purpose. delivery systems.Information In fact, about several specific lectins carbohydrate were approved recognition by Food by andlectin Drug receptors Administration was gathered for that herein, purpose. plus Informationthe specific organs about specific where those carbohydrate lectins can recognition be found by within lectin the receptors human was body. -

Multiomics of Azacitidine-Treated AML Cells Reveals Variable And

Multiomics of azacitidine-treated AML cells reveals variable and convergent targets that remodel the cell-surface proteome Kevin K. Leunga, Aaron Nguyenb, Tao Shic, Lin Tangc, Xiaochun Nid, Laure Escoubetc, Kyle J. MacBethb, Jorge DiMartinob, and James A. Wellsa,1 aDepartment of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, University of California, San Francisco, CA 94143; bEpigenetics Thematic Center of Excellence, Celgene Corporation, San Francisco, CA 94158; cDepartment of Informatics and Predictive Sciences, Celgene Corporation, San Diego, CA 92121; and dDepartment of Informatics and Predictive Sciences, Celgene Corporation, Cambridge, MA 02140 Contributed by James A. Wells, November 19, 2018 (sent for review August 23, 2018; reviewed by Rebekah Gundry, Neil L. Kelleher, and Bernd Wollscheid) Myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and acute myeloid leukemia of DNA methyltransferases, leading to loss of methylation in (AML) are diseases of abnormal hematopoietic differentiation newly synthesized DNA (10, 11). It was recently shown that AZA with aberrant epigenetic alterations. Azacitidine (AZA) is a DNA treatment of cervical (12, 13) and colorectal (14) cancer cells methyltransferase inhibitor widely used to treat MDS and AML, can induce interferon responses through reactivation of endoge- yet the impact of AZA on the cell-surface proteome has not been nous retroviruses. This phenomenon, termed viral mimicry, is defined. To identify potential therapeutic targets for use in com- thought to induce antitumor effects by activating and engaging bination with AZA in AML patients, we investigated the effects the immune system. of AZA treatment on four AML cell lines representing different Although AZA treatment has demonstrated clinical benefit in stages of differentiation. The effect of AZA treatment on these AML patients, additional therapeutic options are needed (8, 9). -

Identification of a Novel Deletion Region in 3Q29 Microdeletion Syndrome by Oligonucleotide Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization

Korean J Lab Med 2010;30:70-5 � Original Article∙Diagnostic Genetics � DOI 10.3343/kjlm.2010.30.1.70 Identification of a Novel Deletion Region in 3q29 Microdeletion Syndrome by Oligonucleotide Array Comparative Genomic Hybridization Eul-Ju Seo, M.D.1, Kyung Ran Jun, M.D.1, Han-Wook Yoo, M.D.2, Hanik K. Yoo, M.D.3, and Jin-Ok Lee, M.S.4 Departments of Laboratory Medicine1, Pediatrics2, and Psychiatry3, University of Ulsan College of Medicine and Asan Medical Center, Seoul; Asan Institute for Life Sciences4, Seoul, Korea Background : The 3q29 microdeletion syndrome is a genomic disorder characterized by mental retardation, developmental delay, microcephaly, and slight facial dysmorphism. In most cases, the microdeletion spans a 1.6-Mb region between low-copy repeats (LCRs). We identified a novel 4.0- Mb deletion using oligonucleotide array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) in monozy- gotic twin sisters. Methods : G-banded chromosome analysis was performed in the twins and their parents. High- resolution oligonucleotide array CGH was performed using the human whole genome 244K CGH microarray (Agilent Technologies, USA) followed by validation using FISH, and the obtained results were analyzed using the genome database resources. Results : G-banding revealed that the twins had de novo 46,XX,del(3)(q29) karyotype. Array CGH showed a 4.0-Mb interstitial deletion on 3q29, which contained 39 genes and no breakpoints flanked by LCRs. In addition to the typical characteristics of the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome, the twins had attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder, strabismus, congenital heart defect, and gray hair. Besides the p21-activated protein kinase (PAK2) and discs large homolog 1 (DLG1) genes, which are known to play a critical role in mental retardation, the hairy and enhancer of split 1 (HES1) and antigen p97 (melanoma associated; MFI2) genes might be possible candidate genes associated with strabis- mus, congenital heart defect, and gray hair. -

Table SII. Significantly Differentially Expressed Mrnas of GSE23558 Data Series with the Criteria of Adjusted P<0.05 And

Table SII. Significantly differentially expressed mRNAs of GSE23558 data series with the criteria of adjusted P<0.05 and logFC>1.5. Probe ID Adjusted P-value logFC Gene symbol Gene title A_23_P157793 1.52x10-5 6.91 CA9 carbonic anhydrase 9 A_23_P161698 1.14x10-4 5.86 MMP3 matrix metallopeptidase 3 A_23_P25150 1.49x10-9 5.67 HOXC9 homeobox C9 A_23_P13094 3.26x10-4 5.56 MMP10 matrix metallopeptidase 10 A_23_P48570 2.36x10-5 5.48 DHRS2 dehydrogenase A_23_P125278 3.03x10-3 5.40 CXCL11 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11 A_23_P321501 1.63x10-5 5.38 DHRS2 dehydrogenase A_23_P431388 2.27x10-6 5.33 SPOCD1 SPOC domain containing 1 A_24_P20607 5.13x10-4 5.32 CXCL11 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 11 A_24_P11061 3.70x10-3 5.30 CSAG1 chondrosarcoma associated gene 1 A_23_P87700 1.03x10-4 5.25 MFAP5 microfibrillar associated protein 5 A_23_P150979 1.81x10-2 5.25 MUCL1 mucin like 1 A_23_P1691 2.71x10-8 5.12 MMP1 matrix metallopeptidase 1 A_23_P350005 2.53x10-4 5.12 TRIML2 tripartite motif family like 2 A_24_P303091 1.23x10-3 4.99 CXCL10 C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 A_24_P923612 1.60x10-5 4.95 PTHLH parathyroid hormone like hormone A_23_P7313 6.03x10-5 4.94 SPP1 secreted phosphoprotein 1 A_23_P122924 2.45x10-8 4.93 INHBA inhibin A subunit A_32_P155460 6.56x10-3 4.91 PICSAR P38 inhibited cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma associated lincRNA A_24_P686965 8.75x10-7 4.82 SH2D5 SH2 domain containing 5 A_23_P105475 7.74x10-3 4.70 SLCO1B3 solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B3 A_24_P85099 4.82x10-5 4.67 HMGA2 high mobility group AT-hook 2 A_24_P101651 -

CD24, CD27, CD36 and CD302 Gene Expression for Outcome Prediction in Patients with Multiple Myeloma

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, 2017, Vol. 8, (No. 58), pp: 98931-98944 Research Paper CD24, CD27, CD36 and CD302 gene expression for outcome prediction in patients with multiple myeloma Elina Alaterre6,2, Sebastien Raimbault6, Hartmut Goldschmidt4,5, Salahedine Bouhya7, Guilhem Requirand1,2, Nicolas Robert1,2, Stéphanie Boireau1,2, Anja Seckinger4,5, Dirk Hose4,5, Bernard Klein1,2,3 and Jérôme Moreaux1,2,3 1Department of Biological Haematology, CHU Montpellier, Montpellier, France 2Institute of Human Genetics, CNRS-UM UMR9002, Montpellier, France 3University of Montpellier, UFR Medecine, Montpellier, France 4Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik V, Universitätsklinikum Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany 5Nationales Centrum für Tumorerkrankungen, Heidelberg, Germany 6HORIBA Medical, Parc Euromédecine, Montpellier, France 7CHU Montpellier, Department of Clinical Hematology, Montpellier, France Correspondence to: Jérôme Moreaux, email: [email protected] Keywords: multiple myeloma; prognostic factor; gene expression profiling; cluster differentiation Received: February 10, 2017 Accepted: August 27, 2017 Published: October 30, 2017 Copyright: Alaterre et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0 (CC BY 3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. ABSTRACT Multiple myeloma (MM) is a B cell neoplasia characterized by clonal plasma cell (PC) proliferation. Minimal residual disease monitoring by multi-parameter flow cytometry is a powerful tool for predicting treatment efficacy and MM outcome. In this study, we compared CD antigens expression between normal and malignant plasma cells to identify new potential markers to discriminate normal from malignant plasma cells, new potential therapeutic targets for monoclonal-based treatments and new prognostic factors. -

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Biosciences Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12399-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD93 C1QR1,C1qRP, MXRA4, C1qR(P), Dj737e23.1, GR11 – – – – – + + – – + – CD220 Insulin receptor (INSR), IR Insulin, IGF-2 + + + + + + + + + Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF1R), IGF-1R, type I IGF receptor (IGF-IR), CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD94 KLRD1, Kp43 HLA class I, NKG2-A, p39 + – + – – – – – – CD221 Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I), IGF-II, Insulin JTK13 + + + + + + + + + CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD178, FASLG, APO-1, FAS, TNFRSF6, CD95L, APT1LG1, APT1, FAS1, FASTM, CD95 CD178 (Fas ligand) + + + + + – – IGF-II, TGF-b latency-associated peptide (LAP), Proliferin, Prorenin, Plasminogen, ALPS1A, TNFSF6, FASL Cation-independent mannose-6-phosphate receptor (M6P-R, CIM6PR, CIMPR, CI- CD1d R3G1, R3 b-2-Microglobulin, MHC II CD222 Leukemia -

Engineered Type 1 Regulatory T Cells Designed for Clinical Use Kill Primary

ARTICLE Acute Myeloid Leukemia Engineered type 1 regulatory T cells designed Ferrata Storti Foundation for clinical use kill primary pediatric acute myeloid leukemia cells Brandon Cieniewicz,1* Molly Javier Uyeda,1,2* Ping (Pauline) Chen,1 Ece Canan Sayitoglu,1 Jeffrey Mao-Hwa Liu,1 Grazia Andolfi,3 Katharine Greenthal,1 Alice Bertaina,1,4 Silvia Gregori,3 Rosa Bacchetta,1,4 Norman James Lacayo,1 Alma-Martina Cepika1,4# and Maria Grazia Roncarolo1,2,4# Haematologica 2021 Volume 106(10):2588-2597 1Department of Pediatrics, Division of Stem Cell Transplantation and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA; 2Stanford Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA; 3San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, Milan, Italy and 4Center for Definitive and Curative Medicine, Stanford School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, USA *BC and MJU contributed equally as co-first authors #AMC and MGR contributed equally as co-senior authors ABSTRACT ype 1 regulatory (Tr1) T cells induced by enforced expression of interleukin-10 (LV-10) are being developed as a novel treatment for Tchemotherapy-resistant myeloid leukemias. In vivo, LV-10 cells do not cause graft-versus-host disease while mediating graft-versus-leukemia effect against adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Since pediatric AML (pAML) and adult AML are different on a genetic and epigenetic level, we investigate herein whether LV-10 cells also efficiently kill pAML cells. We show that the majority of primary pAML are killed by LV-10 cells, with different levels of sensitivity to killing. Transcriptionally, pAML sensitive to LV-10 killing expressed a myeloid maturation signature.