Volume 59 – June 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Class of 2021 Highlights

Class of 2021 ◊ 78 seniors will enroll in 44 different colleges in 21 different states and the District of Columbia ◊ 82% of seniors received merit scholarships, totaling over $11.5 million in college-sponsored, four-year scholarships ◊ $148,000 average scholarship per student ◊ 83% of the senior class completed one or more AP examinations Photo by Phillips Mitchell ◊ 5 National Merit Finalists; 2 National Merit Commended Scholars ◊ 4 seniors will participate in intercollegiate athletics ◊ 49% of seniors scored 28 or above on the ACT; 30% of the class scored 30 or above Class of 2021 College Acceptances & Choices (in bold) Alfred University Lake Forest College University of Cincinnati American University Landmark College University of Colorado-Boulder Asbury University Loyola University Chicago University of Denver Auburn University Loyola University New Orleans University of Florida Baldwin Wallace University Lynn University University of Georgia Belmont Abbey College Marymount Manhattan College University of Illinois Belmont University Miami University University of Kentucky Birmingham-Southern College Morehead State University University of Louisville Bluegrass Community and Technical College Mount St. Joseph University University of Maryland Boston University Muskingum University University of Massachusetts Butler University North Carolina State University University of Mississippi Carnegie Mellon University Northeastern University University of Pittsburgh Case Western Reserve University Northwestern University University of Richmond -

COLLEGE and CAREER FAIR TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 Th 6 - 7:30 P.M

2019 Stark County COLLEGE AND CAREER FAIR TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 th 6 - 7:30 p.m. $30.7 96% 7 Canton Memorial Civic Center MILLION SUCCESS RATE U.S. NEWS AND IN GRANTS AND 10-YEAR GRADUATE WORLD REPORT 1101 Market Avenue North, Canton, OH 44702 SCHOLARSHIPS SUCCESS AVERAGE RANKING FOR BEST ARE OFFERED COLLEGES IN THE 2019 Stark County Whether you’ve just begun to look for the right EACH YEAR MIDWEST college or narrowed down your search to a few, the Stark County College and Career Fair will be a great opporitunity for you. COLLEGE AND VISIT OUR CAMPUS Make plans now to attend the largest college career fair in Stark County! Visit us at Mount Union to experience our beautiful CAREER FAIR campus, state-of-the-art facilities, and dynamic campus life Representatives from more than 100 colleges and firsthand. Visit, mountunion.edu/visit-campus to schedule universities will be available to provide information a visit. TUESDAY, OCTOBER 8 on choosing a college, persuing a career and 6 - 7:30 p.m. planning your future. DOWNLOAD OUR MOBILE APP Canton Memorial Civic Center • No registration is necessary Download the Discover Mount Union App to learn more 1101 Market Avenue North, Canton, OH 44702 • Free admission about our upcoming events, explore our academic majors, • Contact your school counselor for more information and enagage with one of our admission counselors. • More than 100 colleges and universities present The Discover Mount Union App is available on both Apple and Android devices. • Learn the fundamentals of financial aid 1101 Market Ave N • Contact your guidance office for more information Canton, OH 44702 • Free parking in the Cultural Center parking lot 6 - 7:30 p.m. -

Fall 2018 UPDATE

FALL 2018 UPDATE muskingum on the move: Renovated Patton Dining Hall Enhances the Student Experience L to R: Dean of Students Susan Waryck Kayla Wilkerson ’19 Luke Lloyd ’19 Aramark Executive Chef Christopher Boyd INSIDE: Welcoming The Class of 2022 I Celebrating Reunion Weekend @ Homecoming UPDATE Copyright © 2018. Muskingum Update is published by Muskingum University, 163 Stormont Street, New Concord, Ohio 43762. Editor: Annette Giovengo Nolish. Contributors and Photography: Josh Chaney ’10, Amanda Mlikan ’14, Chris Crook, Tom Caudill ’05 MAE, Josh Franzos. Magazine Printing: Knepper Press. Contents Online Archives: From the President’s Desk 3 muskingum.edu/UpdateMag Editorial correspondence: Muskie Spaces: [email protected] or Muskingum on the Move: Patton Dining Hall Renovation 4 740-826-8134. Learning: Welcoming our Newest Muskies 7 Address changes: [email protected] or Excellence: Making An Impact 11 740-826-8131. Athletics: Catching up with the Fighting Muskies 14 Gatherings: Reunion Weekend @ Homecoming 2018 16 Sharing The Legacy 21 In Memoriam 23 @muskingumalumni From the President’s Desk Greetings to all Muskingum Alumni and Friends! Muskingum is on the move. The 2018-19 academic year is underway with an exciting energy and a sharp focus on how the Muskingum experience impacts our students and alumni, and how they impact the world. Through the pages of this UPDATE, we are proud to share many examples of our Muskingum momentum. Our students helped shape an important aspect of campus life with their input into a $3.7 million renovation of Patton Dining Hall, an investment created in partnership with our dining service provider, Aramark Corporation. -

College Acceptance List

College Acceptances – Classes of 2016-2020 University of Aberdeen Clafin University - 1 Harvard University - 2 Newcastle University University of Southhampton - 1 (Scotland) - 2 Claremont McKenna College - 1 Harvey Mudd College - 2 (England) - 1 Spelman College - 3 Adephi University - 1 Clark University - 2 Haverford College - 2 North Carolina A&T State University of St. Andrews Agnes Scott College - 1 Clarkson University - 1 High Point University - 5 University - 3 (Scotland) - 1 University of Akron - 10 Clemson University - 11 Hillsdale College - 4 North Carolina State St. Bonaventure University - 1 University of Alabama - 17 Colby College - 5 Hobart & Wm. Smith University - 1 St. Francis University - 1 Allegheny College - 1 Colgate University - 2 Colleges - 2 University of North Carolina - 3 St. Lawrence University - 2 American University - 12 Colorado College - 3 Hofstra University - 4 Northeastern University - 15 St. Louis University - 8 Amherst College - 2 Colorado State University - 8 Howard University - 1 Northern Kentucky Stevens Institute of Anderson University - 1 University of Colorado, Univeristy of Idaho - 1 University - 17 Technology - 1 Arizona State University - 3 Boulder - 26 University of Illinois - 17 Northwestern University - 8 University of Stirling University of Arizona - 14 Columbia College Chicago - 4 Illinois Institute of University of Notre Dame - 3 (England) - 2 Art Academy of Cincinnati - 1 Columbia University - 3 Technology - 2 Oberlin College - 7 Syracuse University - 16 Auburn University - 2 Columbus College -

Muskingum Adult Program 2020-2021 Student Guidebook

MUSKINGUM ADULT PROGRAM 2021-2022 STUDENT GUIDEBOOK CONTENTS Getting Started .................................................. 3 Academic Information ....................................... 13 Frequently Asked Questions Academic Advising Muskingum University Mission Statement Academic Credit Academic Dishonesty, Plagiarism Muskingum Adult Program (MAP) Profile ....... 4 Degrees Academic Load Majors Academic Standards Policy Expenses Academic Standing Admission Requirements Academic Probation How to Register Notification How to Pay Restrictions Financial Aid Policies and Student Responsibilities Academic Dismissal Student Identification Cards Readmission Course Confirmation and Cancellations Add/Drop Period Grades and Transcripts Attendance Auditing Courses General Information .......................................... 6 Commencement Non-Discrimination Statement Course Withdrawals Availability of Student Records Degree Requirements Campus Communication MAP General Requirements Consumer Information Core Requirements Annual Crime Statistics Disclosure Distribution Requirements New Concord Campus Resources and Services Exemption from Requirements Admission ........................................................... 8 Full-Time Status MAP Application Procedures Grade Point Average Financial Aid Policies and Student Responsibilities Grading Policy Experiential Learning Credit Non-Degree Seeking Students Financial Aid Order of Appeal Leave of Absence Registration MAP Tuition and Fees Special Programs Muskingu Univrsity Scholarships and Awards -

2009-2010 Undergraduate Catalog

Muskingum University Non-Profit Org. 2009-2010 MUSKINGUM UNIVERSITY CATALOG COURSE Office of Admission US Postage 163 Stormont Street PAID New Concord, OH 43762 New Concord, OH Permit No. 4 UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CATALOG 2009-2010 MUSKINGUM UNIVERSITY MUSKINGUM UNIVERSITY 2009 – 2010 UNDERGRADUATE ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2010 – 2011 UNDERGRADUATE ACADEMIC CALENDAR Fall Semester 2009 Fall Semester 2010 Monday, August 24 Classes Begin Monday, August 30 Classes Begin Tuesday, August 25 (11 a.m.) Opening Convocation Tuesday, August 31 (11 a.m.) Opening Convocation Friday, August 28 (5 p.m.) Add/Drop period ends Friday, September 3 (5 p.m.) Add/Drop period ends Monday, September 7 Labor Day (classes as usual) Monday, September 6 Labor Day (classes as usual) Friday, September 25 Last day to withdraw from 1st half classes Friday October 1 Last day to withdraw from 1st half classes Friday, October 2 Early assessment grades due to Registrar Friday, October 8 Early assessment grades due to Registrar Friday, October 9 1st half classes end Friday, October 15 1st half classes end Monday, October 12 2nd half classes begin Monday-Tuesday, October 18-19 Fall break (no classes) Friday, October 16 Add/Drop ends for 2nd half classes Wednesday, October 20 2nd half classes begin Monday-Tuesday, October 19-20 Fall break (no classes) Tuesday, October 26 Add/Drop ends for 2nd half classes Tuesday, November 3 Last day to withdraw from full semester courses Tuesday, November 9 Last day to withdraw from full semester courses Tuesday, November 17 Last day to withdraw from -

Colleges & Universities

Bishop Watterson High School Students Have Been Accepted at These Colleges and Universities Art Institute of Chicago Fordham University Adrian College University of Cincinnati Franciscan University of Steubenville University of Akron Cincinnati Art Institute Franklin and Marshall College University of Alabama The Citadel Franklin University Albion College Claremont McKenna College Furman University Albertus Magnus College Clemson University Gannon University Allegheny College Cleveland Inst. Of Art George Mason University Alma College Cleveland State University George Washington University American Academy of Dramatic Arts Coastal Carolina University Georgetown University American University College of Charleston Georgia Southern University Amherst College University of Colorado at Boulder Georgia Institute of Technology Anderson University (IN) Colorado College University of Georgia Antioch College Colorado State University Gettysburg College Arizona State University Colorado School of Mines Goshen College University of Arizona Columbia College (Chicago) Grinnell College (IA) University of Arkansas Columbia University Hampshire College (MA) Art Academy of Cincinnati Columbus College of Art & Design Hamilton College The Art Institute of California-Hollywood Columbus State Community College Hampton University Ashland University Converse College (SC) Hanover College (IN) Assumption College Cornell University Hamilton College Augustana College Creighton University Harvard University Aurora University University of the Cumberlands Haverford -

4-Year Public Campuses: Bowling Green State

Campuses Who Participated in the Changing Campus Culture Report by the Deadline: 4-Year Public Campuses: Bowling Green State University Central State University Cleveland State University Kent State University Miami University Northeast Ohio Medical University The Ohio State University Ohio University Shawnee State University The University of Akron University of Cincinnati The University of Toledo Wright State University Youngstown State University 2-Year Public Campuses: Belmont College Central Ohio Technical College Cincinnati State & Technical College Clark State College Columbus State Community College Edison State Community College Hocking College Lakeland Community College Lorain County Community College Marion Technical College North Central State College Northwest State Community College Owens Community College Rhodes State College Rio Grande Community College Sinclair Community College Southern State Community College Stark State College Terra State Community College Washington State Community College Zane State College Private Campuses: Ashland University Aultman College of Nursing Baldwin Wallace University Bluffton University Capital University Case Western Reserve University Cedarville University The Christ College of Nursing Cleveland Institute of Music Columbus College of Art & Design Defiance College Franciscan University of Steubenville Franklin University Heidelberg University John Carroll University Kettering College Malone University Marietta College Mercy College of Ohio Mount Carmel College of Nursing Mount St. Joseph University Mount Vernon Nazarene University Muskingum University Oberlin College Ohio Northern University Ohio Wesleyan University Otterbein University Tiffin University University of Dayton University of Northwestern Ohio The University of Findlay University of Mount Union Ursuline College Walsh University Wilmington College Wittenberg University Xavier University *Eastern Gateway Community College & Denison University submitted their reports after the deadline; therefore, their data is not included in the posted report. -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

Ohio Colleges and University Websites

OHIO COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITY WEBSITES 4-Year Public Universities & Regional Campuses Bowling Green State University www.bgsu.edu BGSU-Firelands www.firelands.bgsu.edu Central State University www.centralstate.edu Cleveland State University www.csuohio.edu Kent State University www.kent.edu Kent State Ashtabula www.ashtabula.kent.edu Kent State East Liverpool www.eliv.kent.edu Kent State Geauga www.geauga.kent.edu Kent State Salem www.salem.kent.edu Kent State Stark www.stark.kent.edu Kent State Trumbull www.trumbull.kent.edu Kent State Tuscarawas www.tusc.kent.edu Miami University www.muohio.edu Miami University Hamilton www.regionals.muohio.edu Miami University Middletown www.regionals.muohio.edu Ohio State University www.osu.edu Ohio State Agricultural Tech. Inst. www.ati.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Lima www.lima.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Mansfield www.mansfield.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Marion www.marion.ohio-state.edu Ohio State Newark www.newark.osu.edu Ohio University www.ohio.edu Ohio University-Eastern Campus www.ohio.edu/eastern Ohio University-Chillicothe Campus www.chillicothe.ohio.edu Ohio University-Lancaster Campus www.ohio.edu/lancaster Ohio University-Southern Campus www.southern.ohio.edu Ohio University-Zanesville Campus www.ohio.edu/ zanesville Shawnee State University www.shawnee.edu The University of Akron www.uakron.edu University of Akron-Wayne www.wayne.uakron.edu University of Cincinnati www.uc.edu University of Cincinnati-Clermont www.clc.uc.edu University of Cincinnati- Raymond Walters www.rwc.uc.edu University -

Presbyterian Related Colleges and Universities

PRESBYTERIAN RELATED COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES THIS LIST WAS APPROVED AT THE 2014 GENERAL ASSEMBLY. Agnes Scott College – Decatur, GA Maryville College – Maryville, TN Alma College – Alma, MI Milikin University – Decatur, IL Arcadia University – Glenside, PA Missouri Valley College – Marshall, MO Austin College – Sherman, TX Monmouth College – Monmouth, IL Belhaven University – Jackson, MS Montreat College – Montreat, NC Blackburn College – Carlinville, IL Muskingum University – New Concord, OH Bloomfield College – Bloomfield, NJ Presbyterian College – Clinton, SC Buena Vista University – Storm Lake, IA Queens University of Charlotte – Charlotte, NC Carroll University – Waukesha, WI Rhodes College – Memphis, TN Centre College – Danville, KY Rocky Mountain College – Billings, MT Coe College – Cedar Rapids, IA Schreiner University – Kerrville, TX The College of Idaho – Caldwell, ID St. Andrews University – Laurinburg, NC College of the Ozarks – Point Lookout, MO Sterling College – Sterling, KS The College of Wooster – Wooster, OH Stillman College – Tuscaloosa, AL Davidson College – Davidson, NC Trinity University – San Antonio, TX Davis & Elkins College – Elkins, WV Tusculum College – Greeneville, TN Eckerd College – St. Petersburg, FL Universidad de InterAmericana – San Juan, PR Hampden-Sydney College – Hampden-Sydney, VA University of Dubuque – Dubuque, IA Hanover College – Hanover, IN University of Jamestown – Jamestown, ND Hastings College - Hastings, NE University of the Ozarks – Clarksville, AR Illinois College – Jacksonville, IL University of Pikeville – Pikeville, KY Johnson C. Smith University – Charlotte, NC University of Tulsa – Tulsa, OK King University – Bristol, TN Warren Wilson College – Asheville, NC Lafayette College – Easton, PA Waynesburg University – Waynesburg, PA Lake Forest College – Lake Forest, IL Westminster College – Fulton, MO Lees-McRae College – Banner Elk, NC Westminster College – New Wilmington, PA Lindenwood University – St. -

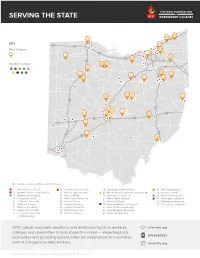

Serving the State

SERVING THE STATE 15 29 16 KEY 13 Main Campus 22 2 6 23 12 Satellite Campus 28 11 8 30 3 19 1 25 33 17 20 26 14 9 27 24 7 32 10 4 21 5 31 18 (#) Indicates number of Ohio satellite campuses 1. Ashland University (7) 10. Franklin University (20) 19. University of Mount Union 28. Tin University (6) 2. Baldwin Wallace University (2) 11. Heidelberg University 20. Mount Vernon Nazarene University (4) 29. Ursuline College 3. Bluton University (2) 12. Hiram College 21. Muskingum University 30. Walsh University (2) 4. Capital University 13. John Carroll University 22. Notre Dame College 31. Wilmington College (3) 5. Cedarville University 14. Kenyon College 23. Oberlin College 32. Wittenberg University 6. Defiance College 15. Lake Erie College 24. Ohio Dominican University (1) 33. The College of Wooster 7. Denison University 16. Lourdes University 25. Ohio Northern University 8. University of Findlay 17. Malone University 26. Ohio Wesleyan University 9. Franciscan University 18. Marietta College 27. Otterbein University of Steubenville OFIC solicits corporate donations and distributes funds to member info@ofic.org colleges and universities to help students in need — impacting local economies and providing opportunities for corporations to boost their 614.469.1950 pool of college-educated workers. www.ofic.org © Copyright 2018-19 The Ohio Foundation of Independent Colleges. All rights reserved KEEPING INVESTMENTS LOCAL OFIC partners exclusively with Ohio-based independent colleges and universities that are dedicated to improving Ohio’s educated workforce.